Chapter 66 Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Epidemiology

The soft tissue sarcomas account for approximately 7% of all pediatric cancers. Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) comprises 40% of this group and the other nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas (NR-STS) comprise the remainder.1,2 This results in 350 patients with RMS and 500 with NR-STS (divided about 2 : 1 between high and low grade) available for participation in clinical trials in the United States annually. Based on prior clinical trials, 75% of children with RMS have required radiation therapy (RT), and, based on the presence of high-grade disease only, approximately two thirds of children with NR-STS would receive radiation. This yields 600 sarcoma cases annually for the study of radiation-specific clinical trial questions, training of young radiation oncologists, and study of radiation-specific long-term sequelae.

Patients with RMS have benefited from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) sarcoma studies (formerly the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group [IRSG]). The trials conducted by these groups have defined the combined modality management of children with RMS in North America and allowed the randomized comparisons of new chemotherapeutics as well as RT strategies that would not be possible without the cooperative group structure. These approaches, as well as the specifics of modern RT are discussed in this chapter. Treatment of children with NR-STS has been less well defined. Local therapy approaches have evolved from adult paradigms, incorporating limb salvage over amputation, adjuvant irradiation, and, subsequently, preoperative RT approaches.3–6 Despite an adult parallel to draw from, little prospective research has been conducted in the pediatric NR-STS population. An ongoing trial through COG (ARST0332) seeks to address some of these deficiencies delivering both preoperative and postoperative RT in conjunction with surgery and chemotherapy to define the role of these local and systemic approaches in a comprehensive clinical trial.

Biologic Characteristics and Pathology

Rhabdomyosarcoma

RMS is broadly classified as one of the small, round, blue cell malignancies of childhood.7 The histologic subtypes, in order by worsening prognosis, include embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (ERMS), the most common form (with spindle cell and botryoid comprising two favorable variants), alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS), and undifferentiated sarcoma. Patients with undifferentiated sarcoma were previously enrolled on the IRSG clinical trials in a fashion similar to ARMS. Currently, these patients receive systemic therapy similar to patients with Ewing’s sarcoma. Light microscopy often describes ERMS with spindle-shaped cells and ARMS with small, round, blue cells forming alveolar-like spaces, although tumor biopsy specimens may also look like collections of poorly differentiated cells complicating definitive diagnosis by hematoxylin and eosin staining alone. Immunohistochemical staining can include positivity for MyoD.8 Cytogenetic events occur in ERMS with a loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 11p and in ARMS with translocations between chromosomes 2 and 13 or 1 and 13. These represent loci of PAX3 and PAX7 (chromosomes 2 and 1) and their fusion with FKHR on chromosome 13. These fusion proteins act as transcription factors and are diagnostic of ARMS.7 Other genetic abnormalities and syndromes associated with RMS include neurofibromatosis type 1 (with a prevalence of 1 : 200 noted on IRSG-IV), Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.9–11

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma

The pediatric NR-STS comprise a heterogeneous group of tumors managed homogeneously owing primarily to the limitations in both patient numbers and effective chemotherapy. The most common histologies noted in practice and clinical trials include synovial cell sarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), although several rarer variants including rhabdoid tumor and infantile fibrosarcoma are almost exclusive to the pediatric age group.12,13 Although many NR-STSs have no genetic signature, several histologic variants do have specific translocations or deletions12,14 (Table 66-1).

TABLE 66-1 Genetic Abnormalities: Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas

| Histology | Genetic Abnormality |

|---|---|

| Synovial cell sarcoma | t(X;18); fusion SYT-SSX |

| Clear cell sarcoma | t(12;22); fusion EWS-ATF1 |

| Rhabdoid tumor | Deletion 22q; INI1 deletion |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumor | t(11;22); fusion EWS-WT1 |

| Infantile fibrosarcoma | t(12;15); fusion ETV6-NTRK3 |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma | der(17)t(X;17); fusion TFE3-ASPL |

| Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma | t(7;16); fusion FUS-CREB3L2 |

Clinical Manifestations

Rhabdomyosarcoma

The presentation of children with RMS is diverse and relates to the site of involvement and extent of disease. The median age for children presenting with RMS is younger than 5, although another peak occurs in the mid teens. The head and neck region is the most frequent site of involvement and is divided into favorable and unfavorable (parameningeal) sites.15,16 This site comprised 42% of localized presentations in patients enrolled on IRSG III and IRSG IV and serves as an example of the important nature of primary tumor location.17 Metastatic disease occurs 20% of the time at presentation, and nodal involvement is rare (<5%) except for paratesticular (25%) and extremity (24%) sites of disease, which warrant either computed tomography (CT) (paratesticular, <10 years of age), nodal sampling (paratesticular, ≥10 years of age), or sentinel node biopsy (extremity site).18–21

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma

The presentation of NR-STS is often as a painless mass whereas other symptoms are site specific. Approximately half of the cases arise in the extremity, and the incidence increases throughout the adolescent years and into adulthood.22,23 Although the vast majority of soft tissue “masses” are either not real or benign, consideration should be given to malignancy because an ill-chosen surgical approach may compromise future local therapy (Fig. 66-1).

Fifteen to 22 percent of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis, with the lungs being the predominant site of metastatic involvement.13,24 Clear cell sarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and angiosarcoma carry a risk of regional nodal involvement and warrant evaluation of the draining nodal bed(s) with sentinel node sampling.

Staging

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Staging workup is similar for most patients with RMS (Table 66-2). A site-specific history and physical examination should be performed by the treating radiation oncologist at the time of presentation to define the site of primary disease, its extent, and symptoms related to potential metastatic sites of involvement. Attention to cranial nerve involvement for head and neck primary sites as well as attending the examination under anesthesia for genitourinary sites (vaginal, cervix, uterus, bladder, and prostate) will assist in the multidisciplinary discussion regarding staging and local therapy approaches.

TABLE 66-2 Staging Workup and Follow-Up Evaluations for Patients with Rhabdomyosarcoma and Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas | |

|---|---|---|

| Staging | ||

| Clinical | Site-directed history and physical examination | Site-directed history and physical examination |

| Imaging | MRI of primary tumor | MRI of primary tumor |

| CT of chest/abdomen | CT of chest | |

| Bone scintiscan | ||

| Procedures | Biopsy: primary tumor/metastasis | Biopsy: primary tumor/metastasis |

| Extremity: sentinel lymph node biopsy | Histology: specific sentinel lymph node biopsy | |

| Head and neck: cerebrospinal fluid cytology | ||

| Genitourinary: examination under anesthesia | ||

| Follow-up | ||

| Year 1 | History and physical examination every 3 months, laboratory studies, MRI of primary tumor area | History and physical examination, laboratory studies every 3 months, MRI of primary tumor area |

| CT of chest and other metastatic imaging every 3 months | CT of chest every 6 months | |

| Years 2 to 3 | Every 4 months: history and physical examination, laboratory studies, MRI of primary area | Every 5 months: history and physical, laboratory studies, MRI of primary tumor region, CT of chest |

| Every 4 months: CT of chest and other metastatic imaging | ||

| Years 4 to 5 | Every 6 months: history and physical, MRI of primary area, chest radiograph | Annual history and physical laboratory studies, MRI of primary area, CT of chest |

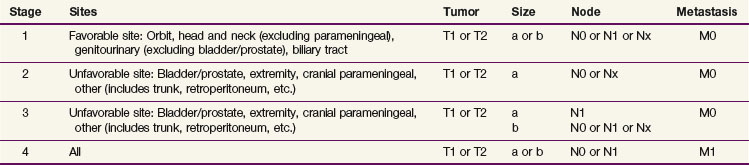

After staging evaluation, a clinical stage should be assigned (outlined in Table 66-3). If surgery has been performed (or after a planned surgical resection or biopsy), a grouping should be defined (Table 66-4). These two factors plus the patient’s histology are combined into a risk classification to assign patients to protocol therapy.

TABLE 66-4 Clinical Grouping System for Rhabdomyosarcoma

| I | Completely resected localized disease |

| Ia | Confined to muscle of origin |

| Ib | Involvement outside of muscle of origin (contiguously) |

| II | Microscopic residual disease and regional nodal involvement |

| IIa | Microscopic residual disease (after gross resection, N0) |

| IIb | Regional nodal involvement (without microscopic residual disease) |

| IIc | Regional nodal involvement (with microscopic residual disease) |

| III | Gross residual disease |

| IIIa | After biopsy |

| IIIb | After gross major resection (>50% of disease) |

| IV | Distant metastasis |

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma

The workup for patients with NR-STS is similar to that for RMS (see Table 66-2). A site-specific history and physical examination should be performed by the treating radiation oncologist at the time of presentation to define the site of primary disease, its extent, as well as symptoms related to potential metastatic sites of involvement.

Evaluation and Definition of Risk Classification

Rhabdomyosarcoma

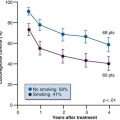

Favorable and unfavorable sites of disease are defined as part of the staging system and are noted in Table 66-3. In addition, histology affects outcome and is related to site of disease; favorable sites of disease in the orbit and genitourinary region are four and five times as likely to be of an embryonal histology as opposed to alveolar or undifferentiated histology. This yields higher disease control rates for localized ERMS compared with ARMS (failure-free survival [FFS], 82% vs. 65%).17 Clinical group (see Table 66-4) is also prognostic of FFS in both ERMS and ARMS. Because of the strong interaction of site, histology, group, and stage, a risk classification system was devised to stratify patients for therapeutic decisions. This resulted in three strata17,25,26:

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Stratification for patients with NR-STS is currently based on retrospective data being tested in a prospective clinical trial.22,23 Low-risk patients are considered as having low-grade tumors (POG grade I or II) as well as high-grade tumors (POG grade III) less than or equal to 5 cm with a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 89%. Intermediate-risk patients with large (>5 cm) high-grade tumors have a 5-year OS of 56%, and high-risk patients with metastatic disease fare poorly, with a 5-year OS of 15%.22

Primary Therapy

Rhabdomyosarcoma

IRSG I (1972–1978) and IRSG II (1978–1984) answered several important questions. Group I (without RT) and group II patients (with RT at doses of 40 to 45 Gy) were noted to fare well with a VA regimen (vincristine, dactinomycin [Actinomycin], omitting cyclophosphamide).15,27 Group III patients did not benefit from the addition of doxorubicin, whereas patients with parameningeal disease treated without directed meningeal RT (a 2-cm meningeal margin) fared significantly worse (OS, 45% vs. 67%).15 Unfortunately, 75% of group IV patients continued to experience progressive disease.

IRSG III (1984–1991) went on to confirm that the VA regimen is equivalent to therapy with VAC and resulted in a progression-free survival of 83% without RT. The addition of doxorubicin to VA did not improve outcome for group II disease, and patients with group III/IV disease did not benefit from the addition of cisplatin or etoposide, with progression-free survival for the latter group remaining at 27%.28

IRSG IV (1991–1997) was the first trial to employ presurgical staging in addition to the grouping system. A randomized question was asked about systemic therapy (now standard VAC vs. VAI [ifosfamide] vs. VIE [ifosfamide/etoposide]) for patients with stage I to III disease. Despite the hope for improvement in overall outcomes, no benefit was seen, and VAC remained the standard of care.29 Patients with group III disease also underwent a randomization between standard RT (50.4 Gy/1.8 Gy daily fraction) and hyperfractionated RT (59.4 Gy/1.1 Gy twice daily fractions). Hyperfractionated RT yielded the same FFS (73%) as conventional RT, and local failure was equivalent (15% vs. 12%).30 IRSG IV, in a retrospective fashion compared with IRSG III, also clarified the management of patients with group I paratesticular disease. Patients younger than age 10 years could be evaluated by CT for retroperitoneal lymphatic involvement (without retroperitoneal lymph node dissection [RPLND]), maintaining a 90% FFS. Those 10 years old or older benefited from RPLND (100% FFS with RPLND compared with 63% with CT alone) to define nodal involvement and the need for subsequent lymphatic RT.29

IRSG V is the last of the intergroup named trials, now named with the COG nomenclature ARST. Patients with group II disease had a reduction in RT dose from 41.4 Gy to 36 Gy for positive surgical margins. Orbital primary tumors were also irradiated using a reduced dose of 45 Gy. Outcome on this low-risk trial appears equivalent to earlier studies, suggesting this is a safe and effective approach.31 Another randomized question was tested for intermediate-risk patients comparing VAC against VAC alternated with VTC (substituting topotecan). This did not improve outcome, with a 4-year FFS of 73% and 68%, respectively.32 High-risk patients during this era underwent phase II window therapy trials incorporating irinotecan. Activity of this agent in combination with vincristine was documented, but FFS remained poor (26% at 2 years).25

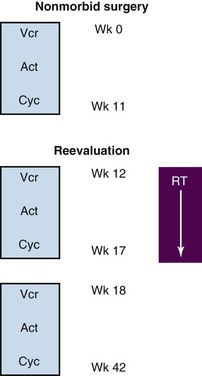

A general algorithm for the integration of chemotherapy, surgery, and RT is shown in Figure 66-2. As a first principle in nearly all North American RMS trials, only a nonmorbid surgical resection should be performed. Amputation, exenteration, or other extensive procedures are discouraged because RT will offer equivalent rates of local control with organ preservation. The timing of RT has varied across studies and disease stage. RT may be integrated after multiple weeks of chemotherapy, facilitating the time necessary to plan with modern radiotherapeutic techniques, allowing some reduction in tumor bulk, as well as potentially integrating a second-look surgical procedure. One exception to this variance is the consistent early introduction of RT in patients with parameningeal disease and intracranial extension.33

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma

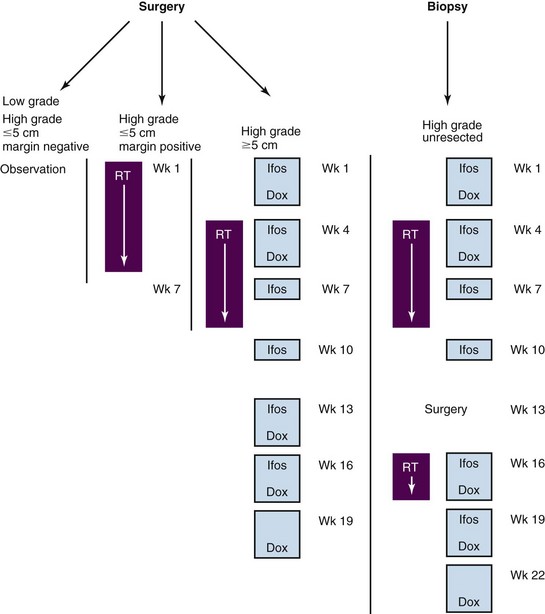

The mainstay for management of children with NR-STS is surgery. Absent this modality, the outcome for patients is poor, with reported event-free survival (EFS) of 33% to 40% at 5 years.23,34 The presence of metastatic disease also predicts for subsequent disease recurrence in the majority of patients (10% EFS).34 All patients, but particularly those with resectable primary site disease, benefit from multidisciplinary discussion before initiation of therapy. Planning the appropriate surgery in the context of tumor grade, size, location, probable surgical margin status, and the patient’s age is the first critical step in the local management of patients with NR-STS. No prospective, completed clinical trials exist in the pediatric population to assist clinicians in selecting patients for specific aspects of local or systemic chemotherapy. The ongoing COG trial (ARST0332), stratified by risk group and local therapy approach, should accrue approximately 400 patients and determine the relative benefit of specific local and systemic therapeutic approaches. This multimodal approach to therapy incorporates standard-of-care approaches for NR-STS adapted for children and is outlined in Figure 66-3. More importantly, this trial will provide a uniform, prospectively treated population of patients on which to evaluate prognostic factors, both clinical and biologic. This could lead to improved risk stratification of patients with NR-STS on future trials.

Radiation Therapy

Indications and Outcomes of Local Therapy

Rhabdomyosarcoma

The role of RT is to eradicate microscopic disease present after resection, treat gross disease, and consolidate visible sites of metastatic involvement. The indications and doses, although complicated by site, can be generalized (Table 66-5). Doses are delivered at 1.8 Gy per fraction daily.

TABLE 66-5 Indication for Radiation Therapy and Prescribed Doses for Patients with Rhabdomyosarcoma

| Disease Status | Embryonal Histology | Alveolar Histology |

|---|---|---|

| Margin negative | No radiation | 36.0 Gy |

| Margin positive | 36.0 Gy | 36.0 Gy |

| Node positive | 41.4 Gy | 41.4 Gy |

| Gross disease | 50.4 Gy | 50.4 Gy |

Data for the treatment of completely resected disease (group I) come from review of prior IRSG trials I to III demonstrating improvement in FFS and OS for patients with ARMS when RT is delivered (73% vs. 44% and 82% vs. 52%, respectively).35 Patients with group II disease received adjuvant radiation, resulting in local failure rates of less than 10%.36 Patients with group III disease have local failure rates of 10% to 15%, depending on site, size, and era of treatment.30,37,38

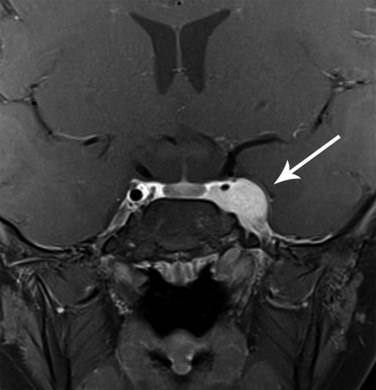

The parameningeal sites (middle ear, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossae, and parapharyngeal region) require special attention to the skull base for adequate coverage of possible intracranial extension. If the timing of RT is not within the first 4 weeks (by protocol design) and intracranial extension is present (Fig. 66-4), then RT should be initiated within the first few weeks of the start of chemotherapy.

The orbit is a favorable site of disease involvement. Local management for this site with RT calls for delivery of 45 Gy at 1.8 Gy daily and yields excellent local control.31 Despite the extremely thin and fragile nature of the bony orbit and the adjacent globe, these two structures are essentially never breached by orbital primary tumors and should be constrained out of the clinical target volume. If tumor does extend through these structures, consideration should be given that this may be parameningeal instead.

Female genitourinary tract (vulvar, vaginal, cervix, and uterus) tumors of ERMS (particularly the botryoid subtype) require adequate local therapy despite the often young age of the patients (frequently <2 years of age [Fig. 66-5]). These patients should either undergo complete resection (group I) at diagnosis or receive adjuvant RT with either external beam or interstitial/intracavitary techniques. Absent adequate local control, high failure rates have been noted in the most recent low-risk clinical trials, prompting the call for improved local control.

Paratesticular RMS is initially managed with radical inguinal orchiectomy with high ligation of the spermatic cord. RPLND, following a surgical template based on laterality, is conducted for all children 10 years of age or older.19 Younger patients may still be managed with CT evaluation of their retroperitoneal lymphatics. Treatment of the lymphatic region is based on the discovery of microscopically or grossly involved lymph nodes.

Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcoma

The best local tumor control rates are achieved in the context of microscopic disease and, as such, surgical resection—wide local (WLE) or marginal—should be the goal for every patient presenting with NR-STS, including with metastatic disease. Clear surgical margins, defined as 5 mm or more of normal tissue beyond the tumor, are beneficial in cases in which RT may be avoided. Conversely, the operating surgeon should proceed with a morbid or disfiguring resection to obtain clear surgical margins because there does not appear to be a significant reduction in local control when adjuvant radiation is delivered.13 Preoperative RT may be employed in the context of larger (>5 cm) tumors or those deemed difficult to initially resect. This is most commonly combined with neoadjuvant doxorubicin and ifosfamide chemotherapy and given concurrently with ifosfamide chemotherapy to a cumulative dose of 45 to 50.4 Gy at 1.8 Gy daily. Postoperative RT either in the form of external beam irradiation or interstitial brachytherapy may be delivered to the tumor bed after margin negative WLE (for high-grade tumors >5 cm) or smaller high-grade tumors with involved surgical margins to doses of 55.8 to 63 Gy at 1.8 Gy daily. Outcomes for either of these approaches have yielded excellent local control, with local failure occurring less than 5% of the time.13

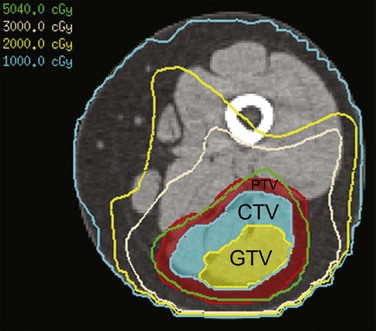

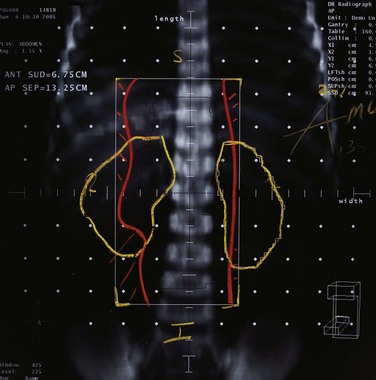

Techniques

All treatment for pediatric patients with soft tissue sarcomas should be volumetric imaging based, require target volume and normal tissue delineation, and allow plan evaluation with dose-volume histograms. Conformal, intensity-modulated, and proton beam RT are all acceptable methods of radiation delivery backed by published outcome data from both cooperative group and institutional clinical trials. Initial and postchemotherapy imaging studies are used to define the extent of disease. MRI is essential because CT provides poor soft tissue definition for evaluating tumor extent. The definitions for gross tumor volume and clinical target volume are described in Table 66-6 for both RMS and NR-STS. Target volume delineation is anatomically constrained, meaning that the radiation oncologist determines the infiltrativeness of the gross tumor toward adjacent normal tissues when designing the shape of the clinical target volume. Planning volumes are institution, site, and treatment specific (e.g., photons compared to protons), but are typically 3 to 5 mm with some form of daily localization (cone-beam CT or fiducials) using photon techniques. Motion may be defined and managed through respiratory gating as necessary.

TABLE 66-6 Target Volume Delineation for Rhabdomyosarcoma and Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Nonrhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas | |

|---|---|---|

| Gross Tumor Volume (GTV) | ||

| Postoperative irradiation | The GTV (more appropriately defined as a CTV) will include the soft tissue tumor bed and soft tissue contiguous with the tumor prior to surgical resection as defined by physical examination, imaging studies, operative notes, and pathology reports. The tumor bed may have “collapsed” in regions and may no longer have the same shape or extent as the presurgical, prechemotherapy volume. If bone was involved, the GTV includes the margin of bone initially involved with tumor. | Same as defined for rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Definitive irradiation/preoperative irradiation | The GTV is defined as the initial tissues in contact with the tumor before therapy and the preirradiation extent of the visible mass, defined by imaging studies before and after chemotherapy and physical examination. Bone involvement warrants targeting the pretherapy extent in bone. Gross residual disease (after an incomplete resection) will be targeted as a definitive irradiation case. Unresected, involved lymph nodes will be included as part of the GTV but may not form one contiguous gross tumor volume depending on tumor and nodal geometry. |

Same as defined for rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Clinical Target Volume (CTV) | The CTV is the GTV with a 1.0-cm anatomically constrained margin of normal tissue accounting for probable pathways of microscopic disease spread. This margin may be reduced (constrained) at fascial planes, bony interfaces, or body cavities based on tumor biology. Nodal involvement is encompassed in the CTV, ideally in a contiguous volume with the GTV. |

The CTV is the GTV with a 1.5-cm anatomically constrained margin of normal tissue accounting for probable pathways of microscopic disease spread. This margin may be reduced (constrained) at fascial planes, bony interfaces, or body cavities based on tumor biology. Nodal involvement is encompassed in the CTV, ideally in a contiguous volume with the GTV. |

Treatment planners should consider adjacent normal tissues and weigh the relative risks of site-specific late effects relative to one another. Every effort should be made to deliver the recommended prescribed dose of radiation because doses utilized in many pediatric malignancies have already been lessened significantly because of concerns of late effects. Parallel-opposed fields should be avoided in nearly all cases to reduce normal tissue exposure to high doses of radiation. Even in extremity sites, treatment with circumferential radiation using an intensity-modulated RT technique (resulting in low doses to the entire circumference of the extremity as opposed to sparing a strip of skin [Fig. 66-6]) has not resulted in clinically documented lymphedema with moderate follow-up.13

Timing

Rhabdomyosarcoma

The timing of delivery of radiation to the primary site of disease in patients with localized rhabdomyosarcoma has varied across the IRSG and COG clinical trials over time. Currently, for patients with low-risk disease, RT is performed after 12 weeks of every-three-week chemotherapy. Intermediate-risk patients receive RT at week 4, primarily based on evidence of improved outcome for patients with parameningeal sites of disease irradiated earlier in the course of therapy.33 Patients with high-risk disease (metastatic) require aggressive chemotherapy. Local control of the primary sites of disease is conducted at week 20, and metastatic sites of disease are irradiated with similar doses at the end of systemic therapy, unless symptomatic. Vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and, in current trials, irinotecan are given concurrently with RT whereas dactinomycin is held, owing to increased skin and mucosal toxicities.

1 Reis LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents. United States SEER Program 1975-1995. National Institutes of Health publication No. 99-4649. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999.

2 Miller RW, Young JL, Novakovic B. Childhood cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:395.

3 Rosenberg SA, Tepper J, Glatstein E, et al. The treatment of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Prospective randomized evaluations of (1) limb-sparing surgery plus radiation therapy compared with amputation and (2) the role of adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1982;196:305-315.

4 Yang JC, Chang AE, Baker AR, et al. Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:197-203.

5 Pisters PW, Harrison LB, Leung DH, et al. Long-term results of a prospective randomized trial of adjuvant brachytherapy in soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:859-868.

6 Kraybill WG, Harris J, Spiro IJ, et al. Phase II study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the management of high-risk, high-grade, soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities and body wall. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Trial 9514. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:619-625.

7 Pappo A, Barr FG, Wolden SL. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Biology and results of the North American Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Trials. In: Pappo A, editor. Pediatric Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006:103-132.

8 Triche T, Schofield D. Pathologic and molecular techniques used in the diagnosis and treatment planning of sarcomas. In: Pappo A, editor. Pediatric Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006:13-34.

9 Sung L, Anderson JR, Arndt C, et al. Neurofibromatosis in children with rhabdomyosarcoma. A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Pediatr. 2004;144:666-668.

10 Li FP, Fraumeni JF. Rhabdomyosarcoma in children. Epidemiologic study and identification of a familial cancer syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969;43:1365.

11 Smith AC, Squire JA, Thorner P, et al. Association of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma with the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:550-558.

12 Spunt SL, Skapek SX, Coffin CM. Pediatric nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas. Oncologist. 2008;13:668-678.

13 Krasin MJ, Davidoff AM, Xiong X, et al. Preliminary results from a prospective study using limited margin radiotherapy in pediatric and young adult patients with high-grade nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:874-878.

14 Fisher CP. Soft tissue sarcomas with non-EWS translocations. Molecular genetic features and pathologic and clinical correlations. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:153-166.

15 Maurer HM, Gehan EA, Beltangady, et al. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study II. Cancer. 1993;71:1904.

16 Newton WA, Soule EH, Hamoudi AB, et al. Histopathology of childhood sarcomas. Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies I and II. Clinicopathologic correlation. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:67.

17 Meza JL, Anderson J, Pappo AS, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors in patients with nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma treated on Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies III and IV. The Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3844-3851.

18 Neville HL, Andrassy RJ, Lobe TE, et al. Preoperative staging, prognostic factors, and outcome for extremity rhabdomyosarcoma. A preliminary report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV (1991-1997). J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:317-321.

19 Wiener ES, Anderson JR, Ojimba JI, et al. Controversies in the management of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma. Is staging retroperitoneal lymph node dissection necessary for adolescents with resected paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma? Semin Pediatr Surg. 2001;10:146-152.

20 Wexler L, Helman L. Rhabdomyosarcoma and the undifferentiated sarcomas. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997:799.

21 La TH, Wolden SL, Rodeberg DA, et al. Regional nodal involvement and patterns of spread along in-transit pathways in children with rhabdomyosarcoma of the extremity. A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010. Jun 11 [Epub ahead of print]

22 Spunt SL, Poquette CA, Hurt YS, et al. Prognostic factors for children and adolescents with surgically resected nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma. An analysis of 121 patients treated at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3697-3705.

23 Spunt SL, Hill A, Motosue AM, et al. Clinical features and outcome of initially unresected nonmetastatic pediatric nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3225-3235.

24 Pappo AS, Rao BN, Jenkins JJ, et al. Metastatic nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcomas in children and adolescents. The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:76-82.

25 Pappo AS, Lyden E, Breitfeld P, et al. Two consecutive phase II window trials of irinotecan alone or in combination with vincristine for the treatment of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma. The Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:362-369.

26 Weigel B, Lyden E, Anderson JR, et al. Early results from Children’s Oncology Group (COG) ARST0431. Intensive multidrug therapy for patients with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:15s.

27 Maurer HM, Beltangady M, Gehan EA, et al. The Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study I. A final report. Cancer. 1988;61:209.

28 Crist WM, Gehan EA, Ragab A, et al. The Third Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:610.

29 Crist WM, Anderson JR, Meza JL, et al. Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3091-3102.

30 Donaldson SS, Meza J, Breneman JC, et al. Results from the IRS-IV randomized trial of hyperfractionated radiotherapy in children with rhabdomyosarcoma. A report from the IRSG. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;51:718-728.

31 Walterhouse DO, Meza JL, Raney RB, et al. Dactinomycin (A) and vincristine (V) with or without cyclophosphamide (C) and radiation therapy (RT) for newly diagnosed patients with low-risk embryonal/botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). An IRS-V report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group (STS COG). J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:18s.

32 Arndt CAS, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. Children’s Oncology Group Study D9803. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5182-5188.

33 Michalski JM, Meza J, Breneman JC, et al. Influence of radiation therapy parameters on outcome in children treated with radiation therapy for localized parameningeal rhabdomyosarcoma in Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group trials II through IV. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(4):1027-1038.

34 Khoury JD, Coffin CM, Spunt SL, et al. Grading of nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma in children and adolescents. Cancer. 2010;116:2266-2274.

35 Wolden SL, Anderson JR, Crist WM, et al. Indications for radiotherapy and chemotherapy after complete resection in rhabdomyosarcoma. A report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies I to III. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3468-3475.

36 Smith LM, Anderson JR, Qualman SJ, et al. Which patients with microscopic disease and rhabdomyosarcoma experience relapse after therapy? A report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4058-4064.

37 Hua C, Merchant TE, Spunt SL, et al. Early results of a prospective study delivering limited margin radiotherapy for pediatric patients with rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:S37.

38 Wharam MD, Meza J, Anderson J, et al. Failure pattern and factors predictive of local failure in rhabdomyosarcoma. A report of group III patients on the Third Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1902-1908.