Chapter 40 Pediatric Palliative Care

According to the World Health Organization, “Palliative care for children is the active total care of the child’s body, mind and spirit, and also involves giving support to the family…Optimally, this care begins when a life-threatening illness or condition is diagnosed and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the underlying illness.” Provision of palliative care applies not only to children with cancer or cystic fibrosis but also those with diagnoses such as complex or severe cardiac disease, neurodegenerative diseases, or trauma with life-threatening sequelae (Table 40-1). While palliative care is often mistakenly understood as equivalent to end-of-life care, its scope and potential benefit extend before and well after end-of-life care and is applicable throughout the illness trajectory. Palliative care emphasizes optimization of quality of life, communication, and symptom control, aims that may be congruent with maximal treatment aimed at sustaining life.

Table 40-1 CONDITIONS APPROPRIATE FOR PEDIATRIC PALLIATIVE CARE

CONDITIONS FOR WHICH CURATIVE TREATMENT IS POSSIBLE BUT MAY FAIL

CONDITIONS REQUIRING INTENSIVE LONG-TERM TREATMENT AIMED AT MAINTAINING THE QUALITY OF LIFE

PROGRESSIVE CONDITIONS IN WHICH TREATMENT IS ALMOST EXCLUSIVELY PALLIATIVE AFTER DIAGNOSIS

CONDITIONS INVOLVING SEVERE, NONPROGRESSIVE DISABILITY, CAUSING EXTREME VULNERABILITY TO HEALTH COMPLICATIONS

Adapted from Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, et al: Pediatric palliative care, N Engl J Med 350:1752–1762, 2004.

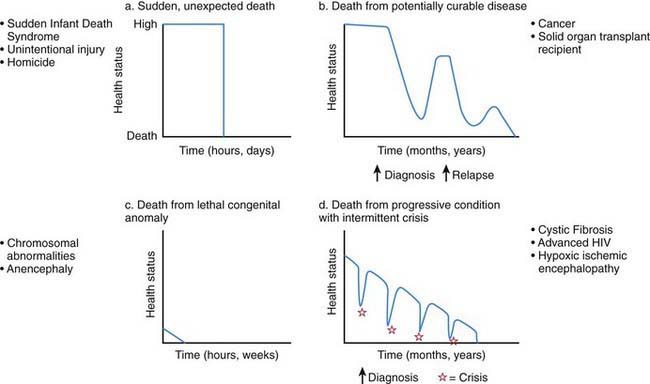

The mandate of the pediatrician and other health care providers to oversee children’s physical, mental, and emotional health and development includes the practice of palliative care for those children who live with a significant possibility of death before adulthood (Fig. 40-1). Many pediatric subspecialists care for children with life-threatening illnesses.

Figure 40-1 Typical illness trajectories for children with life-threatening illness.

(From Field M, Behrman R, editors: When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families, Washington, DC, 2003, National Academies Press, p 74.)

Compared with adult palliative care, pediatric palliative care has:

Medical and technological advances have resulted in an increase in the number of children who live longer, often with significant dependence on new and expensive technologies. These children have complex chronic conditions across the spectrum of congenital and acquired life-threatening disorders (Chapter 39). Children with complex chronic conditions may benefit from simultaneous palliative and curative therapies. These children, who often survive near-death crises followed by the renewed need for rehabilitative and life-prolonging treatments, are best served by a system that is flexible and responsive to changing needs.

Communication, Advance Care Planning, and Anticipatory Guidance

The population of children who die before reaching adulthood includes a disproportionate number of nonverbal and preverbal children who are developmentally unable to make autonomous care decisions. Although parents are legally the primary decision-maker in most situations in the USA, children should be as fully involved in discussions and decisions about their care as appropriate for their developmental status. Utilizing communication experts, child life therapists, chaplains, social workers, psychologists, or psychiatrist to allow children to express themselves through art, play, music, talk, and writing will enhance the provider’s knowledge of the child’s understanding and hopes. Tools such as “Five Wishes” and “My Wishes” have proven to be useful in helping to gently introduce advance care planning to children, adolescents, and their families (www.agingwithdignity.org/index.php).

The Child

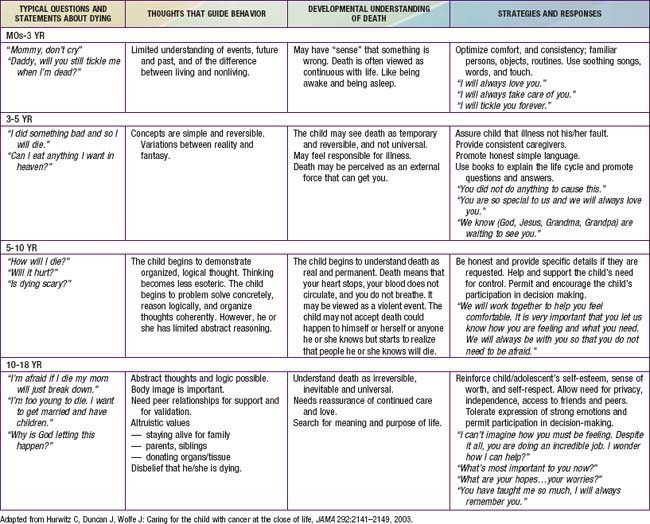

Truthful communication that takes into account the child’s developmental stage and unique lived experience can help to address the fear and anxiety commonly experienced among children with life-threatening illness. Responding in a developmentally appropriate fashion (Table 40-2) to a child’s questions about death, such as “What’s happening to me?” or “Am I dying?” requires a careful exploration of what is already known by the child, what is really being asked (the question behind the question), and why the question is being asked at this particular time and in this setting. It may signal a need to be with someone who is comfortable listening to such unanswerable questions. Many children find nonverbal expression much easier than talking; art, play therapy, and storytelling may be more helpful than direct conversation.

Decision-Making

In the course of a child’s life-limiting illness, a series of difficult decisions need to be made in relation to location of care, medications with risks and benefits, withholding and or withdrawing life-prolonging treatments, experimental treatments in research protocols, and the use of complementary therapies (Chapter 3). Such family decisions are greatly facilitated by opportunities for in-depth and guided discussions around goals of care for their child. This is often accomplished by asking open-ended questions that explore the parent’s and child’s hopes, worries, and family values. Goals of care conversations include what is most important for them as a family, considerations of their child’s clinical condition, and their values and beliefs, including cultural, religious, and spiritual considerations.

Resuscitation Status

Conflicts in decision-making can occur within families, within health care teams, between the child and family, and between the family and professional caregivers (Chapter 3). For children who are developmentally unable to provide guidance in decision-making (neonates, very young children, or children with cognitive impairment), parents and health care professionals may come to different conclusions as to what is in the child’s best interests. Decision-making around the care of adolescents presents specific challenges, given the shifting boundary that separates childhood from adulthood. In some families and cultures, truth telling and autonomy are much less valued compared with family integrity (Chapter 4). Although frequently encountered, differences in opinion are often manageable for all involved when lines of communication are kept open, team and family meetings are held, and the goals of care are clear (Chapters 3, 12, and 106).

Symptom Management

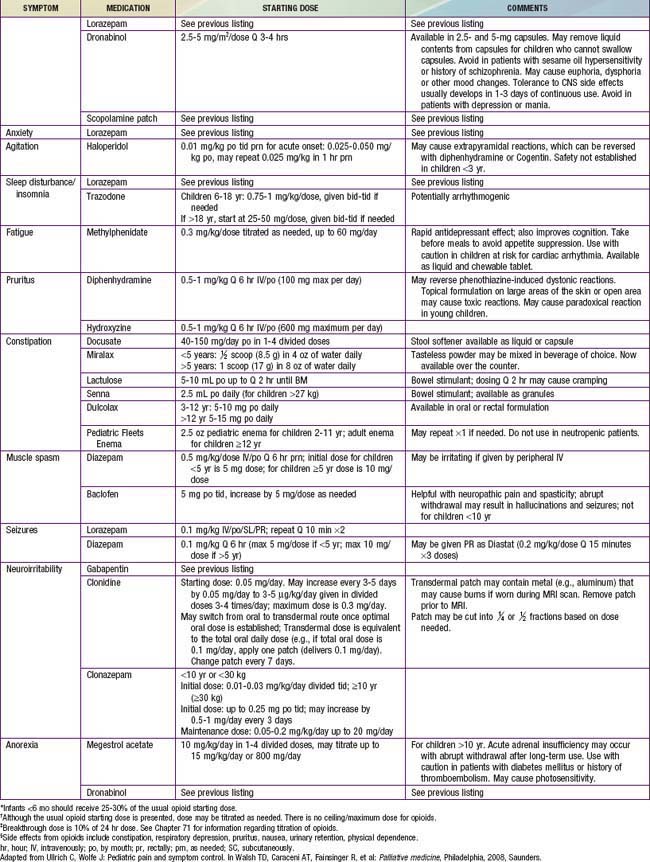

Intensive symptom control is another cornerstone of pediatric palliative care. Alleviation of symptoms reduces suffering of the child and family, and allows them to focus on other concerns and participate in meaningful experiences. Despite increasing attention to symptoms, and pharmacologic and technical advances in medicine, children often suffer from multiple symptoms. Key elements and general approaches to managing symptoms are provided in Table 40-3.

Table 40-3 KEY ELEMENTS OF EFFECTIVE SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

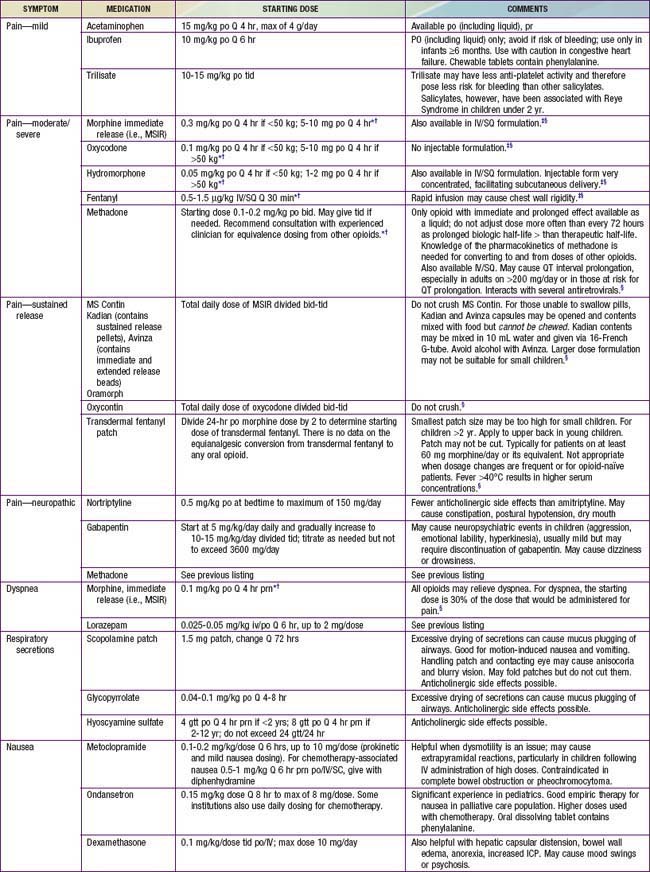

Pain is a complex sensation triggered by actual or potential tissue damage and influenced by cognitive, behavioral, emotional, social, and cultural factors. Effective pain relief is essential to prevent central desensitization, a central hyperexcitation response that may lead to escalating pain, and to diminish a stress response that may have a variety of physiologic effects. Assessment tools include self-report tools for children who are able to communicate their pain verbally, as well as tools based on behavioral cues for children who are unable to do so because of developmental or cognitive limitations. Management of pain is addressed in Tables 40-4 and 40-5 (Chapter 71). Many children with life-threatening illness require opioids for pain at some point in their illness trajectory. Though a stepwise approach to pain is recommended, the step consisting of “weak opioids” is often skipped. The primary opioid in this category, codeine, should generally be avoided because of its side effect profile and lack of superiority over nonopioid analgesics. Furthermore, relatively common genetic polymorphisms in the CYP2D6 gene lead to wide variation in codeine metabolism. Specifically, 10-40% of individuals carry polymorphisms causing them to be “poor metabolizers” who cannot convert codeine to its active form, morphine, and therefore are at risk for inadequate pain control; others are “ultra metabolizers” who may even experience respiratory depression from rapid generation of morphine from codeine. It is therefore preferable to use a known amount of the active agent, morphine.

Table 40-4 GUIDELINES FOR PAIN MANAGEMENT

Table 40-5 PHARMACOLOGIC APPROACH TO SYMPTOMS COMMONLY EXPERIENCED BY CHILDREN WITH LIFE-THREATENING ILLNESS

Children also often experience a multitude of nonpain symptoms. A combination of both pharmacologic (see Table 40-5) and nonpharmacologic approaches (Table 40-6) is often optimal. Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms in children with advanced illness. Children may experience fatigue as a physical symptom (e.g., weakness or somnolence), a decline in cognition (e.g., diminished attention or concentration), and/or impaired emotional function (e.g., depressed mood or decreased motivation). Because of its multidimensional and incapacitating nature, fatigue can prevent children from participating in meaningful or pleasurable activities, thereby impairing quality of life. Fatigue is usually multifactorial in etiology. A careful history may reveal contributing physical factors (uncontrolled symptoms, medication side effects), psychologic factors (anxiety, depression), spiritual distress, or sleep disturbance. Interventions to reduce fatigue include treatment of contributing factors, exercise, pharmacologic agents, and behavior modification strategies. Challenges to effectively addressing fatigue include the common belief that fatigue is inevitable, lack of communication between families and care teams about it, and limited awareness of potential interventions for fatigue.

Table 40-6 NONPHARMACOLOGIC APPROACH TO SYMPTOMS COMMONLY EXPERIENCED BY CHILDREN WITH LIFE-THREATENING ILLNESS

| SYMPTOM | APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|

| Pain | Prevent pain when possible by limiting unnecessary painful procedures, providing sedation, and giving pre-emptive analgesia prior to a procedure (e.g., including sucrose for procedures in neonates) |

| Address coincident depression, anxiety, sense of fear or lack of control | |

| Consider guided imagery, relaxation, hypnosis, art/pet/play therapy, acupuncture/acupressure, biofeedback, massage, heat/cold, yoga, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation, distraction | |

| Dyspnea or air hunger | Suction secretions if present, positioning, comfortable loose clothing, fan to provide cool, blowing air |

| Limit volume of IV fluids, consider diuretics if fluid overload/pulmonary edema present | |

| Behavioral strategies including breathing exercises, guided imagery, relaxation, music | |

| Fatigue | Sleep hygiene |

| Gentle exercise | |

| Address potentially contributing factors (e.g., anemia, depression, side effects of medications) | |

| Nausea/vomiting | Consider dietary modifications (bland, soft, adjust timing/volume of foods or feeds) |

| Aromatherapy: peppermint, lavender; acupuncture/acupressure | |

| Constipation | Increase fiber in diet, encourage fluids |

| Oral lesions/dysphagia | Oral hygiene and appropriate liquid, solid and oral medication formulation (texture, taste, fluidity). Treat infections, complications (mucositis, pharyngitis, dental abscess, esophagitis). |

| Orophayngeal motility study and speech (feeding team) consultation. | |

| Anorexia/cachexia | Manage treatable lesions causing oral pain, dysphagia, anorexia. Support caloric intake during phase of illness when anorexia is reversible. Acknowledge that anorexia/cachexia is intrinsic to the dying process and may not be reversible. |

| Prevent/treat coexisting constipation | |

| Pruritus | Moisturize skin |

| Trim child’s nails to prevent excoriation | |

| Try specialized anti-itch lotions | |

| Apply cold packs | |

| Counterstimulation, distraction, relaxation | |

| Diarrhea | Evaluate/treat if obstipation |

| Assess and treat infection | |

| Dietary modification | |

| Depression | Psychotherapy, behavioral techniques |

| Anxiety | Psychotherapy (individual and family), behavioral techniques |

| Agitation/terminal restlessness | Evaluate for organic or drug causes |

| Educate family | |

| Orient and reassure child; provide calm, nonstimulating environment |

From Sourkes B, Frankel L, Brown M, et al: Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35:345–392, 2005.

Feeding and hydration issues can raise ethical questions that evoke intense emotions in families and medical caregivers alike. Options that may be considered to artificially support nutrition and hydration in a child who can no longer feed by mouth include nasogastric and gastrostomy feedings or intravenous nutrition or hydration (Chapter 3). These complex decisions require evaluating the risks and benefits of artificial feedings and taking into consideration the child’s functional level and prognosis. At times, it may be appropriate to initiate a trial of tube feedings with the understanding that they may be discontinued at a later stage of the illness. A commonly held but unsubstantiated belief is that artificial nutrition and hydration are “comfort measures,” without which a child may suffer from starvation or thirst. This may result in well-meaning but disruptive and invasive attempts to administer nutrition or fluids to a dying child. In dying adults, the sensation of thirst may be alleviated by careful efforts to keep the mouth moist and clean. There may also be deleterious side effects to artificial hydration in the form of increased secretions, need for frequent urination, and exacerbation of dyspnea. For these reasons, it is important to educate families about anticipated decreases in appetite/thirst and therefore little need for nutrition and hydration as the child approaches death. In addition, exploring the meaning that provision of nutrition and hydration may hold for families, as well alternative ways that they may love and nurture their child, may be a helpful way to approach this issue.

When discussing possible therapies or interventions with adolescent patients or with the parents of any ill child, it is important to raise the issue of complementary or alternative medicine. Many families use some form of alternative medicine therapy but do not bring it up with their physician unless explicitly asked (Chapter 59). Although largely unproven, some therapies are inexpensive and provide relief to individual patients. Other therapies may be expensive, painful, intrusive, and even toxic. By initiating conversation and inviting discussion in a nonjudgmental way, the physician can offer advice on the safety of different therapies and may help avoid expensive, dangerous, or burdensome interventions.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:351-357.

Berde CB, Sethna NF. Analgesics for the treatment of pain in children. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1094-1103.

Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, et al. Hospital staff and family: perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1248-1252.

Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

Kolarik RC, Walker G, Arnold RM. Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1949-1954.

Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1175-1186.

Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet. 2008;371:852-864.

Smith AK, Sundore RL, Pérez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families. JAMA. 2009;301:1047-1057.

Sourkes B, Frankel L, Brown M, et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35:345-392.

Stroebe M, Schut H, Strobe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960-1972.

Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1717-1723.