25 Pediatric Orthopedic Emergencies

• Ligaments are stronger than bones in young children.

• The history should be consistent with the injury and the developmental stage of the child.

• Children are poor at localizing pain and often refer symptoms to neighboring joints. The pathologic site in knee pain may be the hip.

• Growth plate injuries are subtle but have the potential to lead to growth arrest.

• Radiographs of the contralateral side are useful as comparison views for the investigation of subtle fractures.

Radial Head Subluxation

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

A number of reduction techniques are used, including the hyperpronation method and the supination-flexion method. The hyperpronation method has proved more effective and appears to be less traumatic.1 With the arm held in extension, the wrist is hyperpronated and a click is sometimes heard. In the supination-flexion approach the examiner places the thumb of one hand over the radial head and provides countertraction. Next, while holding the wrist, the elbow is pulled into extension. The final phase is supination and flexion at the elbow. Most children return to full functioning within 15 minutes, and the child should be observed until full range of motion is regained.

Fractures

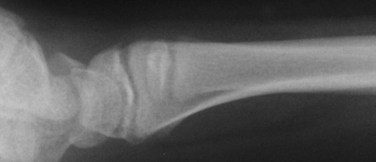

Pediatric bones are less dense and therefore more prone to compression or bending when an axial load is applied. Falls onto an outstretched arm may result in torus or buckle fractures (Fig. 25.1). Greenstick fractures are incomplete, with the cortex remaining intact on one surface. To obtain complete reduction, completion of the fracture is necessary. Bowing fractures result when the force is insufficient to cause a complete break but results in deformation of the osseous structure (Fig. 25.2). Cosmetic deformity and functional abnormality will result without complete reduction. Repair is often difficult because both cortices remain intact.

Salter-Harris Classification of Fractures

The most commonly used system to identify physeal injuries is the Salter-Harris classification. Fractures are categorized as types I through V, with the higher numbers having the greater risk for growth abnormalities. All such injuries require pediatric orthopedic follow-up.2

Type II fractures, the most common type, occur when a piece of the metaphysis remains attached to the epiphysis (Fig. 25.3). They require splinting and generally carry a good prognosis. Types III and IV are intraarticular fractures that also involve the growth plate. In a type III injury, the fracture line extends through the epiphysis into the physis. In type IV, the fracture passes through the epiphysis, physis, and metaphysis. Types III and IV carry a risk for growth retardation, altered joint mechanics, and functional impairment and thus require urgent orthopedic evaluation. Type V fractures are compression injuries and are difficult to visualize on radiographs. The diagnosis is often made retrospectively following a case of growth arrest.

Toddler’s Fractures

If the symptoms persist, one may choose to repeat the films in 7 to 10 days to look for new subperiosteal bone formation. Immobilization is sufficient to promote healing. When the child limps and radiographic findings are negative, a fracture or injury in another location should be considered. Varied pathology, including appendicitis, toxic synovitis, septic arthritis, foot and ankle fractures, soft tissue injuries, and abuse (Box 25.1), may all be manifested as a limp in a toddler.

Box 25.1

Fractures Suggesting Abuse*

Multiple fractures, especially in various stages of healing

Fracture patterns inconsistent with the history

Fractures coexistent with soft tissue injuries consistent with abuse

Lower-extremity fractures in nonambulatory children

Spiral fractures of the humerus

Data from Belfer RA, Klein BL, Orr L. Use of the skeletal survey in the evaluation of child maltreatment. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19:122-4.

Supracondylar Fractures

Classification of the types of supracondylar fractures is based on the extent of the injury: type I is nondisplaced (Fig. 25.4), type II is displaced posteriorly with an intact cortex (Fig. 25.5), and type III is completely displaced with no cortical contact (Fig. 25.6). Type I injuries are managed by immobilization for 4 to 6 weeks. Treatment of type II injuries is based on the extent of the damage, and an orthopedist should be consulted. More severe cases require admission, reduction, and internal fixation, but milder cases may be treated as type I injuries. All type III fractures require closed reduction with pinning in the operating room.

Radiographic findings may be subtle, particularly in type I injuries (Box 25.2). When a fracture line cannot be visualized easily, other findings may assist in making the diagnosis. A posterior fat pad or joint effusion located dorsal to the distal end of the humerus at the level of the olecranon fossa is always pathologic and evidence of a fracture. An anterior fat pad is normal unless it is lifted up and squared off inferiorly into a “sail sign.” A line drawn along the anterior surface of the humerus should intersect the capitellum in its middle third. Posterior displacement of the distal end of the humerus will cause the line to fall further anteriorly or miss the capitellum entirely.

With more severe injuries, the difficulty is not in making the diagnosis but rather recognition and reduction of complications. Morbidity includes range-of-motion abnormalities, neurovascular compromise, and long-term deformities. A thorough examination and documentation of neurovascular status, pain control, and stabilization are mandatory. The limb should be splinted in the deformed position. Motor and sensory function of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves is at risk. Direct vascular injury is uncommon, but because a potential for compartment syndrome does exist, examinations should be repeated frequently and recorded.3

Septic Arthritis

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Children suffering from septic arthritis are frequently ill appearing with a fever of 104° F (40° C) or higher, limited range of motion in the affected joint, and pain and swelling.5 The pain is constant and increases with movement. In the case of septic arthritis of the hip, the child lies in a position of comfort with the hip slightly flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. An infected knee will be erythematous, edematous, warm, and tender to palpation.

Toxic Synovitis

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Although patients will sit in a position of comfort and complain with movement of the limb, the affected joint has full range of motion.5 This is in stark contrast to septic arthritis, in which the child appears systemically ill, is in significant pain, and cannot move the affected join through full range of motion.6

Diagnostic Testing

The white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein findings are usually normal or slightly elevated, consistent with an inflammatory process.5 Radiographs are often normal or may reveal a mild effusion with joint space widening. Because sufficient overlap exists in some manifestations of septic joint and toxic synovitis, synovial fluid is necessary to make the diagnosis (Table 25.1). When obtained, synovial fluid is sterile.

| FINDINGS | SEPTIC ARTHRITIS | TOXIC SYNOVITIS |

|---|---|---|

| Fever (° C) | ≥38.5 | <38.5 |

| Complete blood count (cells/mm3) | ≥12,000 | <12,000 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | ≥2.0 | <2.0 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/hr) | ≥40 | <40 |

Data from Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81:1662-70.

1 Green D, Linares MY, Garcia Pena BM, et al. Randomized comparison of pain perception during radial head subluxation reduction using supination-flexion or forced pronation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:235–238.

2 Brown JH, DeLuca SA. Growth plate injuries: Salter-Harris classification. Am Fam Physician. 1992;46:1180–1184.

3 Campbell CC, Waters PM, Enabs JB. Neurovascular injury and displacement in type III supracondylar fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:47–52.

4 Wall EJ. Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11:76–79.

5 Caird MS, Flynn JM, Leung YL, et al. Factors distinguishing septic arthritis from transient synovitis of the hip in children. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1251–1257.

6 Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1662–1670.