21 Pediatric Gynecologic Disorders

• Prepubertal girls have thin, sensitive vaginal mucosa that is easily irritated.

• If speculum examination is necessary in a young girl, examination under anesthesia should be considered.

• Parents of young girls taken to the emergency department because of gynecologic complaints are often worried about the possibility of sexual abuse but may not verbalize their concern until appropriate questions are asked.

• Most pediatric gynecologic complaints are not related to abuse.

• Most sexually abused children have no abnormalities on examination.

• Emergency department evaluation of possible sexual abuse should focus on identification of patients who require urgent treatment, urgent collection of evidence, or protective custody.

Pathophysiology

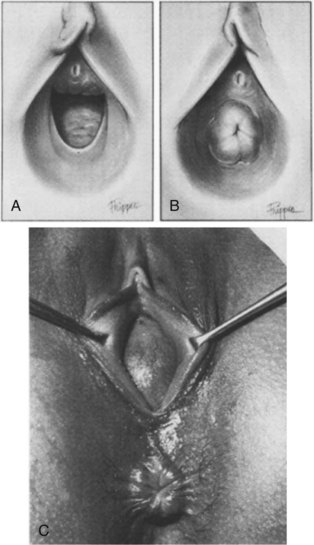

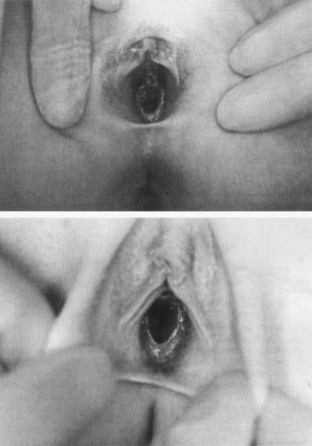

Pediatric gynecologic problems differ from those of adult women chiefly because the vaginal mucosa is thin, dry, and easily irritated in the absence of estrogen. This makes prepubertal girls more sensitive to a variety of chemical, physical, and microbiologic irritants. The normal hymen looks thin, with an average opening of about 4 mm. However, there is great variability in normal hymenal shape, ranging from imperforate to multiple small fenestrations to oval, round, or stellate openings (Fig. 21.1). Abnormal findings that may correlate with vaginal penetration include lacerations of the hymen or a thickened hymen with rolled edges. These findings are extremely difficult to differentiate from normal variations, and photos should always be taken if sexual abuse is suspected. Neonates have swollen labia and thick, moist vaginal epithelium for several weeks after birth, but most prepubertal girls have smooth pink vaginal mucosa and a pale vulva that barely covers the clitoris.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

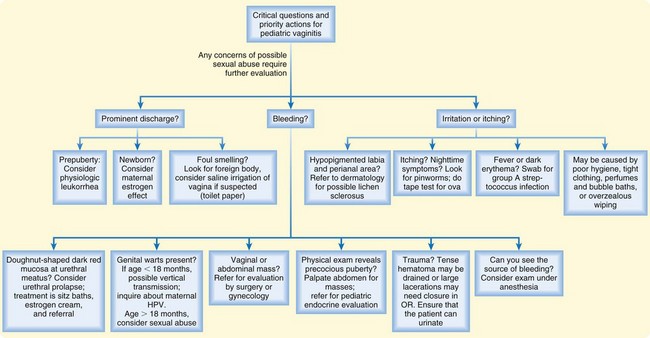

The chief complaints of children with gynecologic problems include vaginal discharge or bleeding, itching or rubbing of the genitals, dysuria or refusal to void, or a foul genital odor noted by caregivers. The initial differential diagnosis can be guided by the predominant complaints (Box 21.1).

Tips and Tricks

Promoting Body Safety While Accomplishing the Necessary Genital Examination

State to the child that you are a doctor or nurse.

Perform the nonthreatening aspects of the physical examination first (listen to the heart and palpate the abdomen).

Review and respect privacy and safe-touching rules.

Stand back and let the parent or other caregiver help the child with undressing.

Sexual Abuse

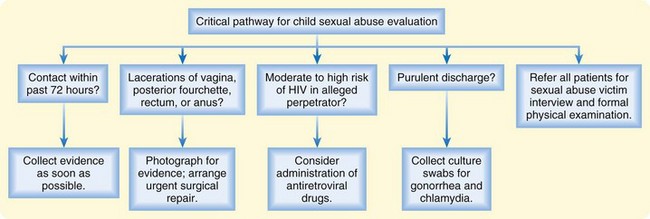

ED evaluation of possible sexual abuse should focus on identifying patients who require urgent treatment, urgent collection of evidence, or protective custody (Fig. 21.2). Open-ended questions by the emergency practitioner (EP) will allow the parents to voice their concerns about possible molestation (this should be done away from the child). When interviewing the patient, history taking should be limited to open-ended questions phrased in child-appropriate language, such as “How did you get this ouchie?” Do not make suggestions that the child may follow in an attempt to please. Do not direct, lead, or ask questions with embedded information because such information can appear in the child’s later responses. Formal interviewing and complete examination are best minimized in the ED and instead carried out by trained personnel. ED providers should be aware of local resources and if possible refer children to a designated child sexual abuse evaluation center.

If abuse is alleged within the past 72 hours, collection of evidence should be undertaken as soon as possible. In studies of forensic evidence collection in prepubertal sexual assault cases, the majority of usable evidence is found on clothing and linen. In one large study of prepubertal sexual assault victims, no swabs were positive for blood after 13 hours or for semen or sperm after 9 hours.1

Genital Examination

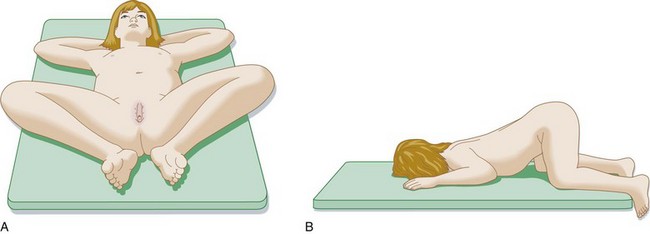

Infants and young toddlers can usually be examined easily if positioned supine in the frog leg position (Fig. 21.3). Prepubertal girls can be examined in either the supine or the prone position. If the child is cooperative, she can lie in the supine position with the feet together and the knees bent and placed apart in the frog-leg position. Visualization can be improved by applying labial traction in two directions—both apart and apart and down (Fig. 21.4).

Some children may be more comfortable hugging their knees to their chest (knee-chest position); labial traction will also be necessary when using this position. In a variation of the knee-chest position, the child rises on her hands and knees and then puts her head down on the examination table (see Fig. 21.3, B).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

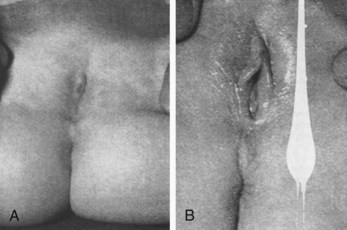

Labial Adhesions

In prepubertal girls, a small section or the entire labia majora may be fused in the midline (Fig. 21.5). Labial adhesion is a self-limited condition and the labia will open with estrogenization at puberty. Though usually asymptomatic, some girls with labial adhesions may have an increased propensity for urinary tract infections. Occasionally, labial adhesions will be noted in the ED because they obscure the urethral meatus and make bladder catheterization difficult or impossible. In these cases, management options include a clean-catch midstream urine collection, a bagged urine specimen, or suprapubic aspiration.

Imperforate Hymen

Imperforate hymen is a rare condition and may be encountered at any age. Neonates and prepubertal girls may have a bulging hymen noted during diaper changing or bathing. More classically, pubertal or postpubertal girls are evaluated for abdominal pain and absence of menses despite the development of breasts and pubic hair. Findings on physical examination may be normal, or a bulging hymen with a dark (bloody) fluid collection behind it may be seen (Fig. 21-6). Ultrasonography will confirm the diagnosis of hydrometrocolpos (a fluid- and blood-filled uterus and vagina). A similar finding may be present with a transverse vaginal septum, but in this condition the hymen is patent.

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis (vaginal discharge with irritation and itching) is a common condition in prepubertal girls. Common complaints include vaginal discharge, itching, redness, dysuria, and bleeding (Fig. 21-7). The prepubertal vaginal mucosa is thin, dry, and very sensitive to minor irritants. Poor hygiene, tight clothing, perfumes and bubble baths, and overzealous wiping are common causes of vulvar irritation and inflammation.

In addition, a variety of infectious agents can cause vulvovaginitis. Pinworm (Enterobius vermicularis) infestation should be suspected in girls with pronounced itching, particularly at night. Vulvovaginitis may be caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection and should be suspected when the vulvar area is beefy red or if the patient has systemic signs of streptococcal infection (fever, scarlatina rash). A retrospective study found that 21% of prepubertal girls with vulvovaginitis were culture positive for group A streptococcal infection.2 Streptoccocal infection is more likely in older girls (school age) and in those with recent exposure to other children with streptoccocal pharyngitis. Rarely, Shigella can cause a similar infectious vaginitis. Yeast does not thrive in the dry mucosa of prepubertal girls, and vaginal candidiasis is extremely rare.

Vaginal Foreign Bodies

Patients with vaginal foreign bodies may have complaints of itching, pain, and bloody or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. Toilet paper is overwhelmingly the most common type of a vaginal foreign body. Insertion of other objects may be the result of exploratory play in very young, developmentally delayed, or sexually abused girls. The possibility of sexual abuse should be considered in girls with vaginal foreign bodies other than toilet paper.3,4

Treatment

Vulvovaginitis

Treatment of vulvovaginitis should be tailored to the underlying cause. For the majority of girls with nonspecific vulvovaginitis, sitz baths and education about hygiene will suffice. Girls with severe dysuria or urinary retention may be able to urinate in the tub during a sitz bath (see the Patient Teaching Tips box). Streptococcal infection can be treated with oral penicillin, clindamycin, or a macrolide antibiotic for 10 days. Shigella infection can be treated with amoxicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Pinworm infestation is easily treated with chewable mebendazole and a repeat dose in 2 weeks. Children with genital warts should be referred to dermatology or pediatric gynecology services for treatment.

Trauma

Straddle injuries involving the vulva and vagina result from falls onto playground equipment, bicycles, or furniture. Although straddle injuries require sensitive handling, they are no more likely than other traumatic injuries to be the result of sexual abuse. If the history does not correlate with the findings on physical examination, further investigation for child abuse is indicated. Frequent findings with straddle injury include abrasions or bruising of the labia, lacerations of the labia or posterior fourchette, tears of the vagina and hymen, and vulvar hematoma.5 If the extent of the internal injury is at all in question, referral to a pediatric gynecologist or pediatric surgeon for examination under anesthesia should be considered. Other indications for referral include tense vulvar hematomas, which may require drainage to avoid tissue necrosis, and lacerations requiring surgical closure. For minor trauma not requiring further referral, ensure that the patient is able to urinate before she is discharged from the ED.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Documentation

Documentation

History—Duration of symptoms; description of any discharge, odor, itching, pain, dysuria, bleeding, enuresis, or urinary retention; history of genital or urinary problems or trauma.

Physical examination—Breast and pubic hair development; abdominal palpation for a mass; genital examination, including color (red or pale), discharge, odor, open sores, bleeding, lacerations, petechiae, bruising, and tears of the mucosa, hymen, posterior fourchette, and anal area; visualization of vaginal masses or foreign bodies; and if necessary, rectal examination to palpate masses or large foreign bodies.

Studies—As indicated: urinalysis with microscopy and culture, bacterial culture, tape test for pinworm eggs, gonorrhea/Chlamydia cultures.

Medical decision making—Concern or lack of concern for abuse; ability of the child to tolerate a gynecologic examination.

Procedures—Success of foreign body removal or suspicion of a retained foreign body; documentation of the timing of collection of sexual abuse evidence and transfer of the evidence to the police.

Photos—Photos should be taken of any abnormal findings or if there is a question of sexual abuse.

Patient instructions—Discussion of hygiene, education about warning signs of a retained vaginal foreign body; record the follow-up plan (phone or visit) for any cultures; if sexual abuse is suspected, document referral to child protection services and the sexual abuse evaluation center.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Discharge Information for Vulvovaginitis

It is normal for little girls to have sensitive skin in the vagina; this is nature’s way of saying that they are not ready to be touched there.

Child should undergo a sitz bath twice a day for 3 to 5 days—sit for 5 minutes in 2 inches of plain water.

If the child will not urinate because of pain or anxiety, try encouraging her to urinate while in the bath water.

Avoid irritants—bubble bath, lotions, perfumed toilet paper.

Wear loose-fitting, cotton clothing and underwear.

Practice proper hygiene—wipe gently from front to back after using the toilet.

Take a complete course of antibiotic treatment for infections when indicated.

1 Christian CW, Lavelle JM, De Jong AR, et al. Forensic evidence findings in pre-pubertal victims of sexual assault. Pediatrics. 2000;106:100–104.

2 Cuadros J, Mazon A, Martinez R, et al. The aetiology of paediatric inflammatory vulvovaginitis. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:105–107.

3 Stricker T, Navratil F, Sennhauser FH. Vaginal foreign bodies. J Paedriatr Child Health. 2004;40:205–207.

4 Herman-Giddens ME. Vaginal foreign bodies and child sexual abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:195–200.

5 Dowd MD, Fitzmaurice L, Knapp JF, et al. The interpretation of urogenital findings in children with straddle injuries. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:7–10.

-year-old girl. Two tiny openings exist—one beneath the clitoris and another near the middle line of fusion. B, Appearance of the same child after 10 days of local application of estrogen ointment.

-year-old girl. Two tiny openings exist—one beneath the clitoris and another near the middle line of fusion. B, Appearance of the same child after 10 days of local application of estrogen ointment.