19 Pediatric Cardiac Disorders

• Congenital heart disease is typically diagnosed in utero or before discharge from the newborn nursery, but delayed manifestations usually occur within the first 2 weeks of life when the ductus arteriosus closes.

• Congenital heart disease should be considered in a neonate who is in shock or has congestive heart failure or cyanosis.

• Subtle signs of cardiac disease in children include sweating, irritability, and poor feeding.

• Echocardiography is used for the diagnosis of structural congenital heart disease.

• Prostaglandin E1 can be lifesaving in cases of ductal-dependent congenital heart disease.

Epidemiology

Structural CHD occurs in approximately 8 in 1000 live births.1 Most congenital lesions are diagnosed in utero or in the newborn nursery, but a significant proportion may not be manifested until 1 to 2 weeks of life, when the ductus arteriosus closes. In fact, a significant proportion of cases of CHD are diagnosed after hospital discharge. Normal findings on newborn evaluation does not rule out potentially significant and lethal lesions, and a high index of suspicion is critical to ensure timely diagnosis.2 Many risk factors for the development of CHD have been identified (Box 19.1), including a family history of CHD, maternal diabetes (associated with ventricular septal defect [VSD], hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and transposition of the great arteries [TGA]), and fetal drug exposure (e.g., Ebstein anomaly with maternal lithium therapy). Pediatric cardiac disease may be challenging because it may mimic more common illnesses, such as sepsis.

Box 19.1 Risk Factors for the Development of Congenital Heart Disease

Risk for congenital heart disease is increased with one affected parent or sibling and is three times greater if two close relatives have such disease.

Maternal diabetes is associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, ventricular septal defect, and transposition of the great arteries.

Maternal phenytoin use is associated with aortic stenosis and pulmonic stenosis.

Maternal lithium use is associated with Ebstein anomaly.

Fetal alcohol syndrome is associated with atrial septal defect and ventricular septal defect.

Rhythm disturbances are also important causes of pediatric cardiac disease and can occur in children with structural heart disease or in those with structurally normal hearts. SVT is the most common pediatric cardiac arrhythmia and includes atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), and preexcitation conditions such as Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome. Congenital complete heart block is associated with maternal connective tissue disease and the presence of anti-Ro/SSA and anti–La-SSB antibodies. Long QTc syndrome may be congenital or acquired; the congenital form is estimated to occur in 1 in 7000 to 10,000 live births.3 Congenital long QTc syndrome may occur in an autosomal dominant form (Romano-Ward syndrome) or in an autosomal recessive form (Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome) associated with sensorineural hearing loss.

Pathophysiology

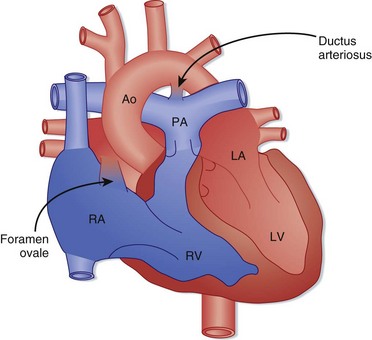

Fetal circulatory anatomy is designed to transport oxygenated blood from the placenta to the systemic circulation while bypassing the lungs (Fig. 19.1). Fetal oxygenation occurs at the placenta, and blood is returned to the right atrium through the ductus venosus after bypassing the liver. Most of the oxygen-rich blood is shunted across the foramen ovale into the left atrium and is then delivered to the systemic circulation via the aorta. Some flow travels from the right atrium into the right ventricle and enters the pulmonary arteries. The pulmonary vasculature is constricted, and flow is shunted through the ductus arteriosus and mixes with blood in the aorta to supply the systemic circulation.

Birth results in a complex series of changes induced by expansion and oxygenation of the lungs. Oxygenation of the lungs leads to a marked decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance and a subsequent increase in pulmonary blood flow. Increasing pulmonary blood flow results in greater return of blood to the left atrium, which functionally closes the foramen ovale (the foramen may remain “probe patent” into adulthood). The decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance is coupled with an increase in systemic vascular resistance, and ductal flow reverses to become left to right. The blood traversing the ductus arteriosus is now highly oxygenated, a change that typically stimulates closure by 48 hours of life. In certain cases, the ductus arteriosus does not close until 1 to 2 weeks of life, and so-called ductal-dependent cardiac lesions may be manifested at this time (Box 19.2). The increased pressure and volume demands on the left ventricle stimulate growth of the left ventricle, and the decreased load on the right ventricle from decreased pulmonary vascular resistance results in a reduction in right ventricular mass.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Infants with previously undiagnosed structural CHD are typically initially seen in the emergency department (ED) with shock, congestive heart failure (CHF), cyanosis, or a combination of these symptoms. Left-sided obstructive lesions such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome and coarctation of the aorta are manifested as shock as the ductus arteriosus closes and the blood supply to the systemic circulation dwindles. Shock can also be the initial sign of total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR) with obstruction. Evidence of poor perfusion, such as lethargy, mottled extremities, tachycardia, and tachypnea, is typically present. Sepsis and other noncardiac conditions (e.g., salt-wasting crisis in congenital adrenal hyperplasia) can cause similar findings. Shock may also be the manifestation of SVT or complete heart block that has become decompensated (Table 19.1).

| TYPE OF SHOCK | POSSIBLE CAUSES |

|---|---|

| Hypovolemic |

CHF is a common manifestation of both structural heart disease and congenital rhythm disturbances. Although respiratory distress, tachypnea, and rales may be present, subtler signs such as poor feeding and hepatomegaly may be the only manifestations of CHF. Assessment of the liver’s edge is a critical portion of the physical examination in these infants. Peripheral edema as a manifestation of CHF is rare in infants. Acyanotic heart diseases with large left-to-right shunts, such as congenital aortic stenosis, interrupted aortic arch, and coarctation of the aorta, are manifested as CHF because blood preferentially flows into the low-resistance pulmonary bed (Box 19.3). TAPVR and VSD can also be manifested as CHF as a result of volume overload of the right ventricle. Rhythm abnormalities such as sustained SVT and congenital complete heart block can likewise be manifested as CHF as a result of poor forward flow.

Cyanosis can be the first manifestation of CHD in infants, and severe lesions are typically diagnosed in utero or in the newborn nursery. Some lesions may escape detection, however, and first be recognized later in the neonatal period. Central cyanosis affecting the lips, mucous membranes, and trunk is due to decreased arterial oxygen saturation and is always pathologic. The differential diagnosis of central cyanosis is presented in Table 19.2. Peripheral cyanosis limited to the extremities or circumoral region is a normal newborn finding but can also be due to non-CHD causes such as sepsis, exposure to cold, and poor cardiac output.

Table 19.2 Differential Diagnosis of Central Cyanosis in Infants

| Cardiac Causes | |

| Right-to-left shunting | |

| Pulmonary Causes | |

| Right-to-left shunting | |

| Ventilation-perfusion mismatch | |

| Hypoventilation | |

| Hematologic Causes | |

| Hemoglobinopathies | |

Rhythm abnormalities such as SVT, long QTc syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and congenital complete heart block may be manifested as syncope, especially in older children. Syncope is a common pediatric finding and typically has a benign prognosis, although documentation of normal electrocardiographic (ECG) findings is important as a screen for more ominous causes of fainting. Though rare, sudden cardiac death as a first manifestation of long QTc syndrome occurs in 9% of affected children and may be an underappreciated cause of sudden infant death syndrome.4

Even though shock, CHF, cyanosis, and syncope are the common manifestation of CHD, the signs and symptoms that bring a pediatric patient to the attention of a health care provider may be more protean. CHD, either structural or arrhythmogenic, should be considered in a child with sweating during feeding, failure to thrive, irritability, chest pain (in older children), unexplained hypertension, or a new murmur. Murmurs are common in the pediatric age group and occur in up to 60% of newborns, the vast majority of whom have structurally normal hearts.5 Most “innocent” murmurs of infancy and childhood are due to either peripheral pulmonary stenosis (PPS) or Still murmurs. PPS murmurs are grade 1 to 2 of 6, midsystolic, high-pitched ejection murmurs best heard over the pulmonary area. Still murmurs are grade 1 to 2 of 6, low-pitched systolic ejection murmurs best heard at the left lower sternal border; they vary with the heart rate and decrease in intensity with the Valsalva maneuver. Characteristics that differentiate between innocent and pathologic murmurs are presented in Table 19.3.

Table 19.3 Differentiating Innocent Murmurs from Pathologic Murmurs

| INNOCENT | PATHOLOGIC | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade (out of 6) | 1-2 | 3 or higher |

| Quality | Soft | Harsh or pansystolic |

| Second heart sound | Normally split | Single or fixed split |

| Other heart sounds | No clicks | Click present |

| Pulse findings | Normal | Decreased femoral pulses |

| Other abnormal findings | Absent | Present |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Lesion-Specific Presentations

Lesions Manifested as Decreased Pulmonary Blood Flow

Acyanotic Structural Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital Aortic Stenosis

Congenital aortic stenosis typically results when an aortic valve is congenitally bicuspid rather than tricuspid. Most infants with aortic stenosis are asymptomatic, and problems do not develop until later in life.6 The condition may be diagnosed in affected children as part of an evaluation for a heart murmur. If the stenosis is severe, symptoms may develop in infancy. Typically, critical congenital aortic stenosis becomes apparent as the ductus arteriosus closes, and the findings consist of heart failure as a result of increased pulmonary blood flow and signs of systemic hypoperfusion. A murmur may not be appreciable because of poor cardiac output. Physical findings include signs of shock with poor peripheral perfusion.

Congenital Rhythm Distubances

Supraventricular Tachycardia

SVT is characterized by a narrow-complex elevated heart rhythm that is regular and generally above 220 beats/min. AVRT, including Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and AVNRT are the two most frequent forms of SVT in children. AVRT is more common in infants and younger children, with AVNRT rising in frequency after 2 years of age. The majority of children with SVT have structurally normal hearts, although SVT is associated with CHD in about 25% of cases.7 Infants may exhibit respiratory distress, poor feeding, and irritability, and the rhythm abnormality may not be recognized until heart failure develops. Older children may have syncope, chest pain, palpitations, or lightheadedness. Sudden cardiac death is rare with SVT unless an underlying structural heart disease is present. Physical findings include tachycardia, hypotension, and signs of heart failure.

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiogram

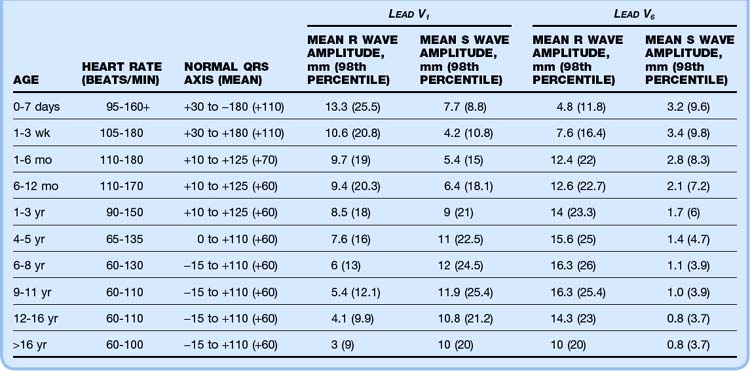

A 12-lead ECG study should be performed on every infant and child in whom heart disease is suspected. If structural CHD is part of the differential diagnosis, a 15-lead ECG study (including leads V3R, V4R, and V7) may give added information. Correct interpretation of pediatric ECG values can be challenging because most normal adult values are abnormal in the newborn period. Normal ECG parameters in children are presented in Table 19.4, whereas Tables 19.5 and 19.6 list ECG findings associated with specific cardiac lesions.8 SVT is typically manifested as a narrow-complex tachycardia with a regular rhythm. Heart rates are generally higher than 220 beats/min, and P waves may be visible. SVT with aberrant conduction (manifested as a wide-complex tachycardia) is rare in the pediatric population, and a wide-complex tachycardia should be considered ventricular in origin until proved otherwise. Long QTc syndrome is characterized by a QTc interval that is prolonged (>440 msec). Acquired causes of a prolonged QTc, such as electrolyte abnormality (hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia) and drug effect (erythromycin, trimethoprim, and others), should be ruled out.

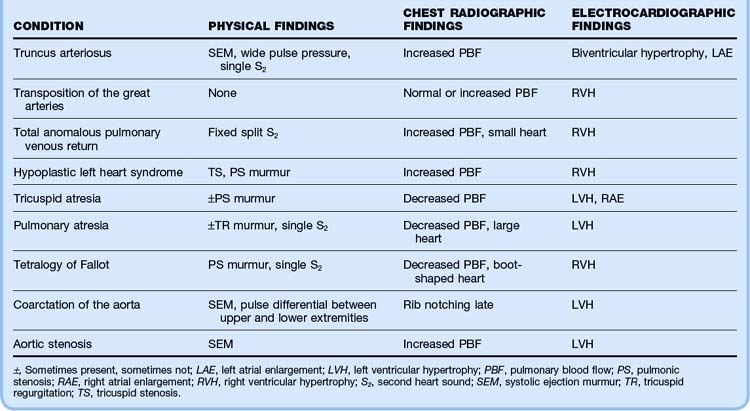

Table 19.5 Physical, Chest Radiographic, and Electrocardiographic Findings in Children with Congenital Heart Disease

Table 19.6 Electrocardiographic Findings in Children with Congenital Rhythm Disturbances

| CONDITION | FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Supraventricular tachycardia |

Chest Radiograph

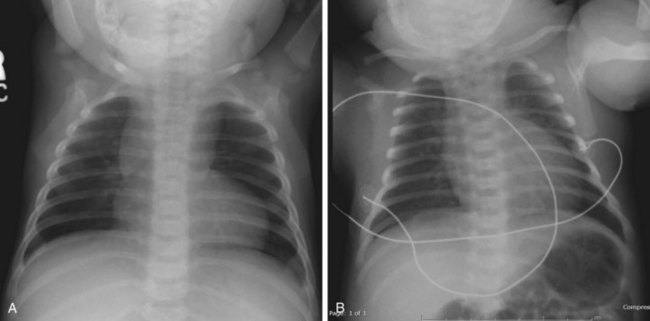

A chest radiograph is useful in the evaluation of suspected cardiac disease because it allows assessment of heart size, pulmonary vascular markings, and situs of the aortic arch. Heart size can help differentiate between a cardiac lesion and sepsis.9 An enlarged heart may be seen with left-sided obstructive lesions such as congenital aortic stenosis, interrupted aortic arch, and critical coarctation of the aorta. Certain CHD lesions have specific radiographic findings, such as the egg-on-a-string pattern seen with TGA and the boot-shaped heart with the tetralogy of Fallot (Fig. 19.2). Structural CHD can be broken down into lesions that cause an increase in pulmonary blood flow and lesions that cause decreased pulmonary blood flow; the presence of increased pulmonary vascular markings on a radiograph can aid in diagnosis (Box 19.4). The aorta is normally left sided, and a right-sided aortic arch can be seen with the tetralogy of Fallot, TGA, and truncus arteriosus.

Fig. 19.2 Classic chest radiographic findings in children with congenital heart disease.

(From Multimedia Library, Children’s Hospital Boston. A, Available at http://www.childrenshospital.org/cfapps/mml/index.cfm?CAT=media&MEDIA_ID=1420; B, Available at http://www.childrenshospital.org/cfapps/mml/index.cfm?CAT=media&MEDIA_ID=1355.)

Hyperoxia Test

Useful in distinguishing cardiac from pulmonary sources of cyanosis, the hyperoxia test hinges on the premise that supplemental oxygen does not increase PaO2 in the presence of an intracardiac shunt to the same degree that it does with isolated pulmonary disease (see the Tips and Tricks box). A child with TGA or severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (i.e., tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, tricuspid atresia) typically has PaO2 values of less than 60 mm Hg during hyperoxia. In lesions such as truncus arteriosus, TAPVR, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome, which involve intracardiac mixing, PaO2 values range between 75 and 150 mm Hg. It is critical to understand that some pulmonary lesions cause right-to-left shunting (persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn) or severe ventilation-perfusion mismatch (meconium aspiration syndrome, pneumonia) and the PaO2 value may not rise above 150 mm Hg with hyperoxia.

Tips and Tricks

The Hyperoxia Test

Have the patient breathe 100% oxygen for 10 minutes (hyperoxia), and then draw a postductal blood sample for arterial blood gas analysis.

Pulmonary disease is suggested if PaO2 with 100% oxygen is greater than 150 mm Hg.

If the PaO2 value is below 150 mm Hg during hyperoxia, a cyanotic cardiac lesion should be suspected.

Treatment

Long QTc Syndrome

The mainstay of therapy in patients in whom congenital long QTc syndrome is diagnosed is beta-blocker therapy, which should be given in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist (Box 19.5). Treatment of torsades de pointes associated with long QTc syndrome should consist of cardioversion (0.5 to 1 J/kg) if the patient is unstable. Magnesium sulfate (25 to 50 mg/kg intravenously) is the antiarrhythmic agent of choice for the treatment of torsades.

Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults: first of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:256.

Brickner ME, Hillis LD, Lange RA. Congenital heart disease in adults: second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:334.

Hoke TR, Donohue PK, Bawa PK, et al. Oxygen saturation as a screening test for critical congenital heart disease: a preliminary study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2002;23:403.

Schwartz PJ, Stramba-Badiale M, Segantini A, et al. Prolongation of the QTc interval and the sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1709.

VanRoekens CN, Zuckerberg AL. Emergency management of hypercyanotic crises in tetralogy of Fallot. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:256.

1 Hoffman JI, Christianson R. Congenital heart disease in a cohort of 19,502 births with long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol. 1978;42:641–647.

2 Keuhl KS, Loffredo CA, Ferencz C. Failure to diagnose congenital heart disease in infancy. Pediatrics. 1999;103:743–747.

3 Schwartz PJ. The long QTc syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol. 1997;22:297–351.

4 Garson A, Jr., Dick M, Fournier A, et al. The long QTc syndrome in children: an international study of 287 patients. Circulation. 1993;87:1866.

5 Braudo M, Rowe RD. Auscultation of the heart—early neonatal period. Am J Dis Child. 1961;101:575–577.

6 Roberts WC. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve: a study of 85 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1970;26:72–83.

7 Tanel RE, Walsh EP, Triedman JK, et al. Five-year experience with radiofrequency catheter ablation: implications for management of arrhythmias in pediatric and young adult patients. J Pediatr. 1997;131:878–887.

8 Robertson J, Shilkofski N. The Harriet Lane handbook: a manual for pediatric house officers, 17th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2005.

9 Pickert CB, Moss MM, Fiser DH. Differentiation of systemic infection and congenital obstructive left heart disease in the very young infant. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998;14:263–267.