8 Patients presenting as emergencies

The pyrexial and septic patient

Patients frequently present to emergency departments with signs and symptoms of infection, as do existing inpatients, irrespective of the cause for initial hospital admission. Severe infections have the potential for significant morbidity and mortality, and therefore it is vital that they are identified and diagnosed speedily by the clinician. Although the majority of patients presenting with fever will have an infective cause which is easily elicited from the history and examination, it is also well recognized that there are many non-infective inflammatory causes. The latter are often debilitating pathologies, where prompt diagnosis helps prompt interventions (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Logical thinking for patients presenting with fever

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Infection | Viral (upper respiratory, lower respiratory, infectious mononucleosis, hepatitis A); bacterial (less common causes include infective endocarditis, meningitis, tuberculosis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, pleural empyema, cholangitis); parasitic (malaria, schistosomiasis); fungal |

| Systemic inflammation | Rheumatoid arthritis; systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); polymyalgia rheumatica; Wegener’s granulomatosis; inflammatory bowel disease; malignant neuroleptic syndrome |

| Malignancy and granulomatous disease | Solid tumours; lymphoma; leukaemia; amyloidosis; sarcoidosis |

| Drugs | Prescription; recreational (e.g. Ecstasy) |

The patient with hypotension or shock

During resuscitation, one needs a quick starting point when assessing the causes of shock. One way to categorize shock is to differentiate causes with wide pulse pressure and narrow pulse pressure (‘pulse pressure’ is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure) (Table 8.2). As a general rule, patients with widened pulse pressure will present with warmer peripheries, and the palpable peripheral pulse may be more ‘bounding’ in nature. Patients with narrowed pulse pressure often possess cooler peripheries, with ‘thready’ peripheral pulses. Although ‘normal’ pulse pressure is often quoted as 40 mmHg, it should be noted that during hypotension this figure should be interpreted with caution. For example, a blood pressure of 75/40 mmHg could be interpreted as having a widened pulse pressure of 35 mmHg, as this is in the context of a low systolic blood pressure.

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Narrow pulse pressure | Hypovolaemic shock (haemorrhage, fluid losses from enteral tract, fluid losses from renal tract, fluid losses from skin (burns)); cardiogenic shock from myocardial failure (coronary ischaemia, acute myocarditis) |

| Widened pulse pressure | Septic shock; anaphylactic shock; neurogenic shock |

The patient with diminished consciousness

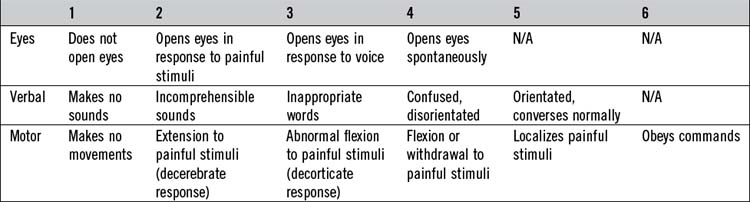

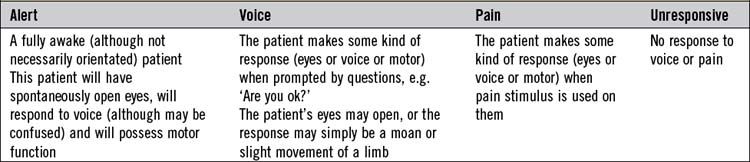

There are several ways to objectively describe the conscious state, though perhaps the two best known ‘scores’ are the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and the ‘AVPU’ score (Tables 8.3 and 8.4). The GCS attributes a score, ranging from 3 to 15. It was originally devised to assess the level of consciousness after head injury, though now is used for almost all acutely presenting patients. When faced with a poorly conscious patient, the usual pairing of resuscitation and diagnostics should be followed. Severe neurological conditions may affect upper airway tone, respiratory drive (e.g. Cheyne–Stokes respiration), vasomotor tone and cardiac rhythm. Also, if the cause of the brain dysfunction is systemic (Table 8.5), this will need to be dealt with. Therefore, it is paramount that the ‘airway, breathing, circulation’ (ABC) algorithm is given due respect. The airway should be supported appropriately (if necessary with endotracheal intubation), the ‘recovery’ lateral position may be required in the unintubated patient to prevent aspiration, hypotension may require vigorous intravenous fluids and monitoring will be required for hypertension and cardiac dysrhythmias.

| Primary cranial diffuse or multifocal disease, where structural lesions will be obvious on imaging | Primary cranial diffuse disease where no structural lesions will be obvious on imaging |

|---|---|

After resuscitation, one should focus on rapidly identifying the cause of brain dysfunction (Table 8.5). If there is an obvious systemic cause, this should already have been dealt with. A brief history from witnesses may reveal preceding hemiparesis, headache, trauma, fit, recreational drug or alcohol intake, or a history of cancer, diabetes, liver or renal disease. Examination should include a full body inspection for features of trauma, fundoscopy, cranial nerves and motor function (including power, tone and reflexes). The power, sensory, cerebellar and visual assessments may not be possible, due to lack of cooperation. One should attempt to examine for meningism by assessing nuchal rigidity (diminished neck flexion with otherwise retained neck movements) and knee extension with the patient supine, with the hip and knee preflexed (pain on knee extension is Kernig’s sign).

Vascular lesions include cerebral arterial or venous thromboses leading to infarcts. Intracranial haemorrhages may be subarachnoid or intracerebral. Relevant cases should be referred early to stroke units or neurosurgeons.

Vascular lesions include cerebral arterial or venous thromboses leading to infarcts. Intracranial haemorrhages may be subarachnoid or intracerebral. Relevant cases should be referred early to stroke units or neurosurgeons.

Primary cranial infections may manifest as meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. One may also become acutely encephalopathic from widespread non-infective inflammatory vascular lesions. With infective and inflammatory pathologies, changes may or may not be evident on cranial imaging. Treatment with antibiotics and/or antiviral agents will initially be empirical, and should not be withheld in favour of preceding lumbar puncture, especially if the patient is critically unwell.

Primary cranial infections may manifest as meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. One may also become acutely encephalopathic from widespread non-infective inflammatory vascular lesions. With infective and inflammatory pathologies, changes may or may not be evident on cranial imaging. Treatment with antibiotics and/or antiviral agents will initially be empirical, and should not be withheld in favour of preceding lumbar puncture, especially if the patient is critically unwell.

After trauma, extradural and subdural haematomata may be suspected, as may subarachnoid and intracerebral haemorrhages. The condition known as ‘diffuse axonal injury’ (DAI) refers to extensive lesions in white matter tracts, and is one of the major causes of unconsciousness after head trauma. ‘Concussion’ is the most common type of traumatic brain injury, where there is temporary loss of brain function with a variety of subsequent physical, cognitive and emotional symptoms. There are usually no changes visible on imaging, and symptoms usually resolve spontaneously over days or weeks. Relevant cases should be referred early to the neurosurgical unit.

After trauma, extradural and subdural haematomata may be suspected, as may subarachnoid and intracerebral haemorrhages. The condition known as ‘diffuse axonal injury’ (DAI) refers to extensive lesions in white matter tracts, and is one of the major causes of unconsciousness after head trauma. ‘Concussion’ is the most common type of traumatic brain injury, where there is temporary loss of brain function with a variety of subsequent physical, cognitive and emotional symptoms. There are usually no changes visible on imaging, and symptoms usually resolve spontaneously over days or weeks. Relevant cases should be referred early to the neurosurgical unit.

Non-convulsive status epilepticus as a cause of altered consciousness is often overlooked. There will often be no obvious clinical clues other than eye deviation or involuntary eye movements. Often, the unconscious patient who has been intensely investigated in the emergency department, and who spontaneously becomes more alert over the subsequent hours, will have had an unwitnessed seizure.

Non-convulsive status epilepticus as a cause of altered consciousness is often overlooked. There will often be no obvious clinical clues other than eye deviation or involuntary eye movements. Often, the unconscious patient who has been intensely investigated in the emergency department, and who spontaneously becomes more alert over the subsequent hours, will have had an unwitnessed seizure.

If opioid overdose is suspected, one may consider administering the opioid antagonist naloxone. This may be essential if the unconscious state is affecting the airway. If the vital observations are stable, however, the benefit of rapid opioid reversal should be weighed against the disadvantages (e.g. disorientation, aggression, vomiting, removal of analgesia).

If opioid overdose is suspected, one may consider administering the opioid antagonist naloxone. This may be essential if the unconscious state is affecting the airway. If the vital observations are stable, however, the benefit of rapid opioid reversal should be weighed against the disadvantages (e.g. disorientation, aggression, vomiting, removal of analgesia).

The psychiatric patient (with or without a known past history) may have a poor conscious level from conversion disorder, or stupor secondary to depression or schizophrenia. Often, the diagnosis will be made after preceding exhaustive negative tests, and will need an expert assessment by the psychiatrist.

The psychiatric patient (with or without a known past history) may have a poor conscious level from conversion disorder, or stupor secondary to depression or schizophrenia. Often, the diagnosis will be made after preceding exhaustive negative tests, and will need an expert assessment by the psychiatrist.

Pupillary examination deserves special mention. As pupillary pathways are resistant to metabolic insult, the identification of absent pupillary reflexes usually implies structural pathology. The brainstem areas governing conscious level are anatomically close to the areas controlling the pupils and so pupillary changes help to identify brainstem pathology causing altered conscious level (Table 8.6).

Table 8.6 Relationship of pupillary changes to site of anatomical damage

| Unilateral pathological dilatation (mydriasis) | Unilateral pathological constriction (miosis) | Mid-point pupil |

|---|---|---|

|

Pupillary fibres close to the origin of the third cranial nerve are especially susceptible when uncal herniation or a posterior communicating aneurysm compresses the nerve This mydriasis is usually accompanied with sparing of oculomotor function When pupillary fibres more distal in the third cranial nerve are affected, the mydriasis usually occurs together with oculomotor dysfunction |

Mid-brain damage: the mid-point pupil shows no reaction to light |

The patient with chest pain

Logical thinking

When life-threatening conditions present with chest pain, the latter is usually central in nature (Table 8.7). The patient should be assessed quickly to see if he is acutely unwell and in need of resuscitation or immediate intervention. An ECG should be recorded immediately as a patient with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction needs to be considered for primary angioplasty or thrombolysis immediately. In addition to complying with the ‘ABC’ of resuscitation, one should be aware of significant accompanying alerting symptoms. These may include severe or interscapular pain (see aortic dissection in Table 8.7), or breathlessness. Acute, life-threatening conditions usually evolve quickly (over minutes), and so symptoms such as chest pain tend to have rapid onset. With oesophageal rupture, there is usually a clear association with vomiting. On examination, one should particularly look for the fine crepitations of pulmonary oedema, the hyperresonant percussion and tracheal deviation of pneumothorax and the asymmetric blood pressure readings consistent with thoracic aortic dissection.

Table 8.7 Logical thinking for patients presenting with chest pain

| Potentially life-threatening conditions – all usually causing central chest pain | Other causes of central chest pain | Causes of pleuritic chest pain |

|---|---|---|

In addition to the history, the risk factors for coronary artery disease and pulmonary embolism (PE) may be factored into the diagnostic process (Box 8.1 and Table 8.8).

Table 8.8 Modified Wells criteria for assessing the risk of pulmonary embolism (PE) in a patient with symptoms consistent with pulmonary embolism

| Clinical parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Clinical evidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | 3 |

| No alternative diagnosis likely other than PE | 3 |

| Heart rate greater than 100 per minute | 1.5 |

| Surgery or immobility in preceding 4 weeks | 1.5 |

| Previous confirmed DVT or PE | 1.5 |

| Haemoptysis | 1 |

| Active malignancy | 1 |

| Total score | Risk |

| >6 | High |

| 2-6 | Moderate |

| <2 | Low |

The breathless patient

When life-threatening conditions present with breathlessness, one should as ever simultaneously resuscitate and use immediate clinical assessment to establish the cause (Table 8.9). The patient should be placed in a safe, monitored environment and clinicians should act quickly if there is evidence of: visible distress, the usage of accessory muscles of respiration, high respiratory rate, high pulse rate, cyanosis or observable low oxygen saturations. Unless there is good evidence that high-flow oxygen has on this occasion, or previous occasions, caused breathing difficulties, the latter should be administered. The clinical assessment will be of life-saving value to direct subsequent therapy, especially if the chest X-ray is not suggestive of one specific pathology.

Table 8.9 Potentially life-threatening conditions presenting as breathlessness

| Clinical assessment | Potentially life-threatening conditions |

|---|---|

| Stridor (may be mistaken for wheeze) | Partial obstruction of trachea or major airway |

| Audible wheeze (one should listen very carefully, as may be very silent) |

While awaiting the urgently requested chest X-ray, one may be in a position to identify additional features to clinch the diagnosis and initiate treatment (Table 8.10). The radiographic features will not be dealt with in this chapter. If stridor as opposed to wheeze is considered, the cause may be evident from the history (airway cancer, foreign body exposure or anaphylaxis). The examiner’s ear should be placed carefully close to the mouth of the patient, to try to establish the source of airflow limitation. Acute stridor is an airway emergency, and the teams of intensive care and ear, nose and throat should be mobilized as quickly as possible.

Table 8.10 Logical thinking for conditions causing breathlessness, including the emergency conditions

| Clinical assessment | Classification | Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Stridor | Large airways disease | Partial obstruction of trachea or major airway |

| Bilateral or diffuse wheeze | Small airways disease | Asthma Acute bronchitis (including bronchitic component to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) Anaphylaxis Pulmonary oedema (presenting as bronchial oedema) Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (though often the wheeze from obesity-related airflow limitation is not heard) |

| Asymmetric features in whole lung field (tracheal deviation, hyperresonance to percussion and diminished breath sounds) | Pleural disease | Pneumothorax |

| Asymmetric features in whole lung field (tracheal deviation, stony dullness to percussion and diminished breath sounds) | Pleural disease | Massive pleural effusion |

| Asymmetric features in whole lung field (tracheal deviation, dullness to percussion and diminished breath sounds) | Large airways disease | Total lung collapse (tumour, foreign body, mucus plug) |

| Diffuse bilateral abnormalities (crepitations) | Diffuse parenchymal disease | Pneumonitis Pulmonary oedema Pulmonary fibrosis |

| Diffuse bilateral abnormalities (bronchial breathing) | Diffuse parenchymal disease | Multilobar or bronchopneumonia |

| Focal abnormality (bronchial breathing) | Focal parenchymal disease | Pneumonia Lobar collapse Bronchiectasis |

| Focal abnormality (dullness to percussion and diminished breath sounds) | Pleural disease | Pleural effusion |

| Bilateral, focal abnormalities (basal stony dullness and diminished breath sounds) | Pleural disease | Bilateral pleural effusions |

| Bilateral, focal abnormalities (bronchial breath sounds) | Parenchymal disease | Bilateral pneumonia (e.g. bibasal pneumonia) |

| Thoracic deformity | Chest wall skeletal disease | Scoliosis Thoracic surgery |

| No obvious abnormality | Pulmonary vascular disease | Pulmonary embolism Pulmonary hypertension |

| Respiratory muscle weakness | Diaphragm paralysis Neuromuscular disease |

|

| Compensatory effort | Metabolic acidosis Anaemia |

|

| Psychogenic | Psychogenic hyperventilation |

This table is not intended to be an exhaustive list. It is aimed at assisting logical thought, particularly with regard to clinical features.

The syncopal patient

Syncope is a frequent cause of presentation to hospital and the emergency department. It may be defined as brief, temporary loss of consciousness with rapid onset and self-termination. The implication is that there is temporary, global hypoperfusion to the brain. The brevity of the event is mostly limited to a few minutes. Although the causes of syncope are often not sinister, the consequences may be catastrophic if, for instance, the onset occurs while driving. The condition should therefore be taken seriously (Table 8.11).

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Cardiac structural disease |

The patient with seizures

If the patient is actively seizing, the ‘ABC’ of resuscitation should be meticulously followed. Intravenous anticonvulsant agents should be administered as rapidly as possible, within the constraints of formulary guidelines. Benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam), phenytoin and levetiracetam are commonly used agents. The aim should be to suppress the seizure as quickly as possible. If there is no success with standard anticonvulsants, the administration of a general anaesthetic (together with intubation, ventilation and admission to intensive care) should be considered. The definition of ‘status epilepticus’ is under continuous scrutiny (Table 8.12).

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Generalized seizure | Involvement of the whole cerebral cortex and therefore abnormalities (e.g. convulsions) may be seen in the whole of the body |

| Consciousness is always impaired | |

| Focal (partial) seizure | Involvement of a focus in the cerebral cortex and therefore abnormalities (e.g. convulsions) may be seen in one part of the body |

| Consciousness may be retained (simple partial seizure) or impaired (complex partial seizure) | |

| There may be secondary generalization (i.e. a focal seizure leading on to a generalized seizure) | |

| Convulsive seizure | For example tonic–clonic, tonic and clonic |

| Non-convulsive seizure | The term ‘absence seizure’ should generally be avoided unless a specific syndromic diagnosis is being made by a clinician experienced in epilepsy |

| Status epilepticus | Historically, one definition has been ‘prolonged seizures for more than 30 minutes’, though, in modern times, it is more sensible to accept that ‘any prolonged seizure’ may be classified as status epilepticus |

Some conditions are commonly misdiagnosed as seizures. Severe exacerbation of extrapyramidal disease may mimic myoclonus. Vasovagal episodes may, on occasions, be followed by jerking of the limbs. Pseudoseizures (seizures simulated by patients for psychological and other complex reasons) are often difficult to differentiate from genuine seizures, even for many experienced neurologists (Table 8.13).

Table 8.13 Awareness of conditions commonly misdiagnosed as seizures

| Condition | Awareness |

|---|---|

| Pseudoseizure | The reasons for patients presenting with contrived movements mimicking seizures are complex. They often occur in known epileptics. The risk of death is significantly higher in epileptics with pseudoseizures, and so the latter needs to be taken seriously and not merely dismissed as a non-organic event. Many experts in epilepsy maintain that with increasing clinical experience, there is increased awareness of the difficulty in the differentiation of seizures from pseudoseizures. There are, however, some features which may lend support to the diagnosis of pseudoseizures: resistance to attempted eye opening by the clinician; limb thrashing and pelvic thrusting; full alertness immediately after the event (i.e. lack of postictal drowsiness) and down-going plantar responses during attack |

| Vasovagal episode | Prolonged vasovagal episodes may lead to cerebral hypoperfusion and brief, self-limiting convulsive-type movements |

| Cranial trauma | This is particularly seen in sports events, where cranial trauma may lead to brief, self-limiting convulsive-type movements, similar to those seen in vasovagal episodes |

| Extrapyramidal disease | Patients may present with worsening or poorly controlled Parkinson’s disease, manifested as severe coarse tremor which, to the untrained eye, may resemble myoclonus |

The patient with dizziness

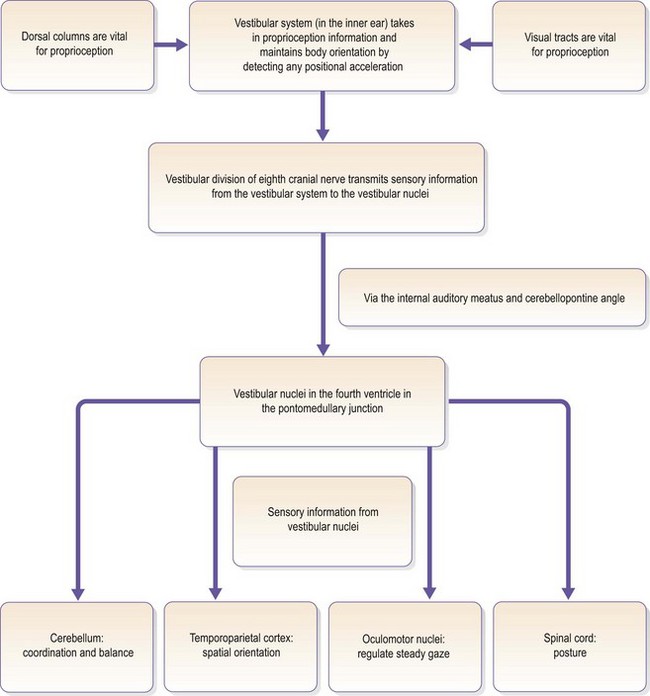

The term ‘dizziness’ (as in the word ‘collapse’), although used frequently by patients and lay people, has no clear precise meaning, and as such always requires medical clarification by the history taker. Any sense of imbalance may be described as dizziness. Balance relies on properly functioning circulation, vestibular apparatus and general sensory function, and it follows that disturbance of these functions may lead to imbalance. It is the duty of the clinician to elicit from the patient whether the features are consistent with presyncope, disequilibrium or true vertigo (Table 8.14). It is important to appreciate the anatomical structures which are relevant; the disruption of any of these will lead to dizziness (Fig. 8.1).

Table 8.14 Logical thinking for conditions associated with dizziness

| Terminology | Examples |

|---|---|

Benign positional paroxysmal vertigo (BPPV) – pathology involving calcium crystals (otoconia) within the labyrinth

Acute labyrinthitis – pathology includes viral infection, allergy or vascular occlusive disease

Ménière’s disease – idiopathic; presumed causes are controversial; may be related to diminished drainage of endolymph from labyrinth and/or autoimmune disease

Posterior circulation cerebrovascular disease or vertebrobasilar migraine

The patient with acute confusion

The causes and mechanisms of confusion should be logically arranged in the mind of the clinician (Table 8.15). Toxaemia from infections, inflammation and drugs will lead to varying degrees of cerebral dysfunction, as will metabolic derangements. Any episode of acute pain or anxiety affects intellectual function. Poor cerebral oxygenation will occur with episodes of hypoxia and diminished cerebral perfusion from circulatory impairment. Any brain pathology may cause cerebral dysfunction; one should be aware that in these cases, confusion may progress to diminished conscious level. The possibility of underlying psychiatric disorder must never be ignored, particularly in the younger patient.

Table 8.15 Logical thinking for conditions causing acute confusion

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Infection | Urine, chest |

| Inflammatory | Acute pancreatitis, vasculitis, ischaemic bowel, myocardial ischaemia |

| Drugs and external toxins | Prescription drugs, recreational drug usage, alcohol (toxicity or withdrawal) |

| The most severe form of alcohol withdrawal is ‘delirium tremens’, a condition which traditionally starts up to 3 days after cessation of heavy alcohol consumption | |

| Metabolic derangement | Hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, hyponatraemia, hypernatraemia, hypercalcaemia, liver dysfunction (synthetic or cholestasis), uraemia, thyroid dysfunction, nutritional deficiency (particularly vitamin B12, thiamine and niacin) |

| Acute pain or anxiety | Urinary retention, severe constipation |

| Psychiatric issues | Depression, schizophrenia |

| Hypoxaemia | Chest infection, pulmonary oedema, pulmonary embolism |

| Circulatory impairment | Cardiac disease (dysrhythmia, systolic dysfunction), sepsis, haemorrhage, prolonged vagal episode |

| Brain pathology | Haemorrhage, ischaemia, seizure disorder, infection (encephalitis and meningoencephalitis), head injury, cerebral vasculitis |

The examination should be targeted, as the patient will most likely not be able to comply with complicated directions which are required in neurological and other assessments. One should commence with the ‘vital’ observations, namely oxygen saturations, respiratory rate, blood pressure (erect and supine) and heart rate. Pyrexia, features of head injury, smell of alcohol, cachexia and features of jaundice or uraemia should be looked for. There may be obvious features of a thyroid disorder. The presence of pain on palpation and abnormalities on chest examination should be identified. Neurological examination will elicit any gross focal or lateralizing features, and also features of meningism. One may conclude with an abbreviated mental test (see Ch. 7). The latter will make the confusion objective, and help track any progress.

The patient with acute headache

It is important to be aware of some distinctive features of the commoner causes of headache (Table 8.16). Missing a subarachnoid haemorrhage is one of the clinician’s worst fears. Distinctive historical features include a sudden-onset, ‘worst ever’ headache. There may have been an episode of loss of consciousness (this may be seen in up to half of all patients presenting with subarachnoid haemorrhage). Features of meningism and raised intracranial pressure are not uncommon. Urgent investigations (cranial CT scan, with targeted lumbar puncture) and specialist referral are paramount. Bacterial meningitis may be rapidly fatal, and treatment with intravenous antibiotics must commence as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Viral meningitis is usually less virulent, though this is not inevitably the case. The headache of meningitis is of acute onset and severe. There are accompanying features of photophobia and neck stiffness. In severe cases, there may be features of raised intracranial pressure. Although pure encephalitis does not produce features of meningism, meningoencephalitis does. Temporal arteritis is a form of vasculitis where the temporal arteries are inflamed and tender. The headache is usually asymmetric. There may be pain in the jaw with chewing (‘jaw claudication’). Vision changes (blurred vision) should prompt urgent treatment with steroids (to prevent complete loss of vision), followed by specialist referral and confirmation of the diagnosis with a temporal artery biopsy. The migrainous headache is typically unilateral and pulsating. The acute period often lasts between 4 and 72 hours, and there may be accompanying nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia (increased sensitivity to sound) or osmophobia (sensitivity to pungent smells).

Table 8.16 Logical thinking for conditions causing acute headache

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Vascular – haemorrhage | Subarachnoid, intracerebral, subdural, extradural |

| Vascular – occlusive | Migraine, temporal arteritis, carotid artery dissection |

| Muscular | Tension-type headache |

| Meningeal irritation | Meningitis (bacterial, viral), subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| Raised intracranial pressure | Space-occupying lesion (tumour, abscess, localized haemorrhage), malignant hypertension, benign intracranial hypertension |

| Drugs and toxins | Oral or sublingual nitrates, carbon monoxide |

| Carbon dioxide retention from respiratory failure | Obstructive sleep apnoea, obesity hypoventilation syndrome |

| Tropical disease | Malaria, any one of the tropical endemic encephalitides |

| Upper respiratory tract infections | Influenza, sinusitis |

| Intraocular pressure | Glaucoma |

| Neuralgia | Trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headache |

The acutely weak patient

The term ‘weakness’ will often be used by patients for a variety of complaints. Although the term should be reserved for the original definition of ‘reduced motor power’, many patients will confess to ‘weakness’ when in fact they are ‘fatigued’ or ‘lethargic’. It is reasonable to infer reduced motor power when weakness is present without significant tiredness. This should be contrasted with fatigue and lethargy, where the diminished power is generalized, commensurate with, and caused by significant tiredness. This should form the basis of initial questioning. (’Do you feel weak because you are tired, or do you think that you have specifically lost muscle power?’) One should realize that often, even the best clinical history taker and the best historian will not differentiate between weakness, fatigue and lethargy. It should be noted that the term ‘fatigue’, which is used here synonymously with the term ‘lethargy’, should not be confused with the neurological term ‘fatiguability’ (Table 8.17).

Table 8.17 Logical thinking for conditions causing acute weakness

| Scenario | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Fatigue or lethargy leading to generalized weakness | Chronic heart failure, chronic lung disease, sleep disorders, anaemia, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic infection, malignancy, depression |

| Loss of motor power leading to generalized weakness | Myasthenia gravis (crisis), post-infectious inflammatory polyneuropathy (‘Guillain-Barré syndrome’), acute myopathy (myositis, rhabdomyolysis) |

| Hemiparesis or hemiplegia (weakness or total paralysis of one side of body) |

Lesion in parasagittal cerebral motor cortex

Lesion in spinal cord (external compression, ischaemia, inflammation, e.g. transverse myelitis, infection, intramedullary space-occupying lesion)

Post-infectious inflammatory polyneuropathy (‘Guillain-Barré syndrome’), acute myopathy (myositis, rhabdomyolysis)

Lesion of nerve roots and cauda equina lesions – usually affects one leg more than the other

Mononeuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex – usually affects one leg more than the other

The patient with abdominal pain

The differentiation of abdominal pain into ‘medical’ and ‘surgical’ causes, although occasionally useful, is often artificial. This type of arbitrary categorization may lead to the missing of ‘non-surgical’ causes including metabolic syndromes and cardiac-referred pain. Furthermore, many patients with acute abdominal pain from surgical conditions will have coexisting medical conditions. It is important, therefore, for the general physician to have a sound working knowledge of the mechanisms and common causes of abdominal pain, so as to know when urgent surgical assessment and intervention is needed (Table 8.18).

Table 8.18 Logical thinking for conditions causing acute abdominal pain

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Enteral visceral pain (usually colicky pain) | Oesophageal spasm or oesophagitis, duodenal ulcer, small bowel enteritis or ischaemia, colitis, colonic obstruction or ischaemia, complex gut perfusion deficit (diabetic ketoacidosis, sickle crisis) |

| Non-enteral visceral pain | Gallbladder pain from cholecystitis, pancreatic pain from pancreatitis or malignancy |

| Peritoneal pain (exacerbated by any changes in intra-abdominal pressure such as coughing, moving) | Perforated enteral viscus (gastric, duodenal, small bowel, appendix, large bowel), perforated non-enteral viscus (gallbladder, spleen, ruptured ectopic pregnancy), inflamed organ (pancreatitis), spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, malignant infiltration, bleeding vessel |

| Non-visceral pain | Aortic aneurysm, renal colic, referred pain |

The patient with haematemesis or melaena

These are common causes of presentation to the emergency department. The term ‘haematemesis’ describes the vomiting of blood, which may be bright red and fresh, or altered (commonly described as ‘coffee grounds’). The presence of haematemesis usually means acute bleeding from a source above the duodenojejunal flexure. ‘Melaena’ is faeces made up of digested blood; it has a black (often described as ‘jet black’), tarry appearance, and possesses a characteristic and offensive smell. Although its presence may suggest acute bleeding from any source proximal to the ascending colon, the commonest source is in the upper-gastrointestinal tract (Table 8.19).

Table 8.19 Logical thinking for conditions causing haematemesis or melaena

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Peptic ulcer disease | Gastric or duodenal (with or without Helicobacter pylori colonization) |

| Inflammation of upper gastrointestinal tract | Reflux oesophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis (the latter two often occur secondary to excess alcohol intake or usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) |

| Oesophageal and/or gastric varices, or portal hypertensive gastropathy | Portal hypertension from chronic liver disease |

| Coagulopathy or increased bleeding tendency | Liver synthetic dysfunction, altered warfarin metabolism (infection, antibiotics), clotting factor deficiencies, thrombocytopenia, anti-platelet drug usage (aspirin, clopidogrel), recent thrombolytic therapy – note: over-anticoagulation may reveal bleeding from specific pathology previously unknown |

| Upper gastrointestinal malignancy or malformation | Oesophageal carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, upper gastrointestinal angiodysplasia (vascular malformation) |

| Mallory–Weiss tear | Tear of lower oesophagus or upper stomach from recurrent vomiting |

| Nose bleeds (epistaxis) | A large amount of swallowed blood may lead to melaena |

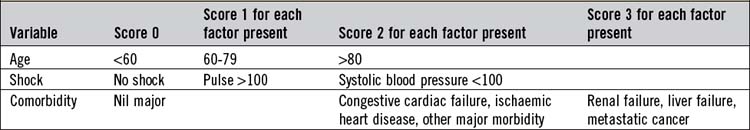

The Rockall score predicts mortality based on initial clinical parameters (Table 8.20). A score of 0 or 1 predicts a very low mortality, and the patient often does not need admission and can go for urgent outpatient investigation. A score of 8 or more predicts a mortality of >25%. There may be occasions when the patient’s history (or collateral history from a relative) of haematemesis or melaena is not substantiated by the overall assessment in the emergency department, and the Rockall score is 0 or 1. In these situations, significant gastrointestinal bleeding is excluded on clinical grounds and occult blood testing of stool or vomit (using urine dipsticks) is not helpful for decision-making.

The patient with diarrhoea and vomiting

Both diarrhoea and vomiting are often non-specific symptoms. In the absence of additional clinical features, the numerous possible causes provide a substantial challenge to the clinician, and therefore history taking and direct questioning are particularly important. Many patients describe ‘diarrhoea’ in a variety of circumstances; it is reasonable to accept the term when there has been at least an increased frequency of watery faeces (Tables 8.21 and 8.22).

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Upper gastrointestinal obstruction | Malignant or benign tumours of upper gastrointestinal tract; benign stricture of upper gastrointestinal tract (e.g. pyloric stenosis) |

| Upper gastrointestinal inflammatory pathology or infections | Acute cholecystitis; acute pancreatitis; acute hepatitis; infective gastritis (often presents as vomiting and diarrhoea, e.g. norovirus) |

| Raised intra-abdominal pressure | Pregnancy |

| Constipation | Almost exclusively in elderly patients |

| Systemic effects of infection | Pneumonia; urinary tract infection |

| Endocrine, metabolic and toxic | Uraemia; cholestasis; hypercalcaemia; diabetic crisis (ketotic and non-ketotic); thyrotoxicosis; hypoadrenalism; drugs (recreational, antibiotics, chemotherapy, opiate analgesic drugs); alcohol |

| Any cause of vertigo | Peripheral rather than central pathology will more commonly lead to nauseation and vomiting (see Ch. 20) |

| Raised intracranial pressure | Space-occupying lesions in the brain; hydrocephalus; benign intracranial hypertension |

| Psychiatric | Bulimia |

Table 8.22 Logical thinking for conditions causing diarrhoea

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Infections (enteritis) | May present as vomiting and diarrhoea (gastroenteritis); viral; bacterial (Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Clostridium difficile); protozoal (particularly giardiasis); amoebae |

| Tumours of small or large intestine | Colonic carcinoma; small bowel lymphoma; rectal villous adenoma |

| Bowel inflammation | Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease; ulcerative colitis); radiation colitis; ischaemic colitis |

| Endocrine, metabolic or toxic | Thyrotoxicosis; hypoadrenalism; Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; drugs (antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) |

| Malabsorption | Coeliac disease; tropical sprue |

| Miscellaneous | Irritable bowel syndrome; ‘overflow’ diarrhoea in the setting of constipation (this occurs almost exclusively in elderly patients); laxative abuse |

The jaundiced patient

The traditional classification of the causes of jaundice into ‘prehepatic’, ‘hepatic’ (or ‘hepatocellular’) and ‘posthepatic’ is tried and tested. A more detailed analysis can be based on the way in which any pathology relates to the metabolism of bilirubin, but this is beyond the scope of this chapter (Table 8.23).

| Mechanism | Common or important examples |

|---|---|

| Prehepatic | Haemolysis, Gilbert’s syndrome (jaundice appears when starving) |

| Hepatic | Acute hepatitis (alcohol, viral hepatitis, autoimmune, drugs); chronic liver disease (either advancement or acute-on-chronic) |

| Posthepatic (obstructive) | Intrahepatic cholestasis (drugs, pregnancy, postviral, chronic liver disease); common bile duct obstruction (gallstone, porta hepatis lymph node, pancreatic cancer, bile duct cancer) |

Some special scenarios

Aggression, to the point of violence, may be seen in consequence to acute confusional states (see Ch. 7) and true psychiatric disorders. Irrespective of the cause, every effort must be made to keep the patient safe from harm, and also safeguard the surrounding staff. This may involve the application of humane physical restraint; the methods used should ideally be predetermined and part of the hospital protocol. The administration of sedation should be planned and prescribed by experienced individuals. Additional help may be provided by psychiatrists, and psychiatrically trained nurses, and by intensive care clinicians if high-dose intravenous sedation is considered.