9 Patients in pain

Classification of pain

Pain is commonly classified according to:

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Physiological: an acute response to an injury.

Physiological: an acute response to an injury.

Inflammatory/nociceptive: pain generated and maintained by inflammatory mediators secondary to an ongoing disease process such as cancer.

Inflammatory/nociceptive: pain generated and maintained by inflammatory mediators secondary to an ongoing disease process such as cancer.

Neuropathic: pain arising from injury to or dysfunction of the central or peripheral nervous system.

Neuropathic: pain arising from injury to or dysfunction of the central or peripheral nervous system.

Psychosomatic: purely psychosomatic pain is rare. However, pain, especially chronic pain, almost invariably has an emotional and behavioural component.

Psychosomatic: purely psychosomatic pain is rare. However, pain, especially chronic pain, almost invariably has an emotional and behavioural component.

Duration

Acute: most commonly a physiological response to an injury. It resolves with the disappearance of a noxious stimulus or within the timeframe of a normal healing process.

Acute: most commonly a physiological response to an injury. It resolves with the disappearance of a noxious stimulus or within the timeframe of a normal healing process.

Chronic: it can either be associated with an ongoing pathological process, such as rheumatoid arthritis or malignancy, or be present for longer than is consistent with a normal healing time. Pain is arbitrarily described as chronic if it persists for longer than 3 months. Chronic pain is often associated with disability and a significant behavioural response. It is sometimes subdivided into pain associated with cancer and pain associated with non-malignant conditions.

Chronic: it can either be associated with an ongoing pathological process, such as rheumatoid arthritis or malignancy, or be present for longer than is consistent with a normal healing time. Pain is arbitrarily described as chronic if it persists for longer than 3 months. Chronic pain is often associated with disability and a significant behavioural response. It is sometimes subdivided into pain associated with cancer and pain associated with non-malignant conditions.

Mechanisms of pain

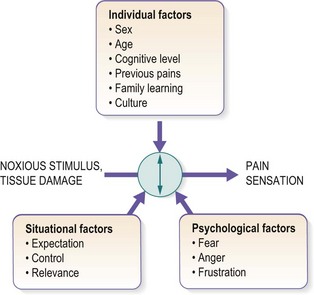

At its simplest, pain is generated by a noxious stimulus that excites the central nervous system. This mechanism was first proposed by Descartes in the sixteenth century and conceptually still holds true, but it is crucial to appreciate that the final subjective experience of pain is shaped by various factors (Fig. 9.1).

In recent years, pain management has increasingly adopted a biopsychosocial model. This has highlighted the need to take into account the interactions between biological, psychological and social factors leading to an individual’s pain experience (see Fig. 9.1).

The patient in pain

1 Is the pain a symptom of ongoing tissue damage, or of another condition that needs to be dealt with by another medical professional?

2 What is the optimal treatment strategy: to either abolish the pain altogether or reduce it to a more bearable level?

History

The pain

The first step is to evaluate the pain and try to understand its mechanisms:

The site of pain: this may give a clue to the underlying pathology.

The site of pain: this may give a clue to the underlying pathology.

Distribution: pain may follow a dermatomal or peripheral nerve distribution, or have no relation to anatomical patterns.

Distribution: pain may follow a dermatomal or peripheral nerve distribution, or have no relation to anatomical patterns.

Character of pain: nociceptive (somatic or visceral) versus neuropathic (Table 9.1).

Character of pain: nociceptive (somatic or visceral) versus neuropathic (Table 9.1).

Duration of pain: this may have a bearing on the level of disability and the associated psychosocial cost.

Duration of pain: this may have a bearing on the level of disability and the associated psychosocial cost.

Rapidity of onset and any precipitating factors: a rapid or relatively recent-onset pain syndrome is more likely to follow a conventional medical model, whereby it is appropriate to search for an underlying cause. Chronic pain requires a more biopsychosocial approach.

Rapidity of onset and any precipitating factors: a rapid or relatively recent-onset pain syndrome is more likely to follow a conventional medical model, whereby it is appropriate to search for an underlying cause. Chronic pain requires a more biopsychosocial approach.

Severity of pain and its change over time: this requires some method of measurement (see below).

Severity of pain and its change over time: this requires some method of measurement (see below).

Alleviating and exacerbating/aggravating factors: these may lead to a better understanding of mechanisms that sustain the pain.

Alleviating and exacerbating/aggravating factors: these may lead to a better understanding of mechanisms that sustain the pain.

Exclusion of more sinister pathology: ‘red flags’. Two most important conditions are not to be missed. One is pain related to cancer and the other is pain related to inflammation.

Exclusion of more sinister pathology: ‘red flags’. Two most important conditions are not to be missed. One is pain related to cancer and the other is pain related to inflammation.

Evaluation of psychosocial elements: ‘yellow flags’ (Box 9.1). These are not life-threatening symptoms, but their presence means that the psychosocial history has special relevance.

Evaluation of psychosocial elements: ‘yellow flags’ (Box 9.1). These are not life-threatening symptoms, but their presence means that the psychosocial history has special relevance.

| Nociceptive | Neuropathic | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of pain | Aching, localized, toothache-like, sharp, squeezing | Shooting, radiating, stabbing, burning, electric shock-like |

| Movement impact | Associated with movement | Independent |

| Physical examination | Normal response | Allodynia, hyperalgesia, vasomotor changes |

| Examples | Injury, postoperative pain | Peripheral neuropathies, shingles, cancer pain |

| Treatment strategies | More classic approach, conventional analgesics | More biopsychosocial approach, conventional analgesics ± non-conventional (antidepressants, anticonvulsants, etc.) |

Box 9.1 Psychosocial aspects of pain

Pain is described as having at least five dimensions, each of which should be addressed:

1 The sensation of pain – the subjective experience.

2 Suffering and distress – the emotional component.

3 Expectations and beliefs – the cognitive component.

4 Verbal (complaints) or non-verbal communication – the behavioural component (illness behaviour) is the way in which a patient responds to and expresses the sensation of pain. It is influenced by various cultural and social factors.

Impact of pain

Consider the effect of pain on the patient’s activity, work, mood, sleep and relationships.

Examination

The purpose of examination is as follows:

To elucidate and evaluate any physical signs associated with a particular pain condition.

To elucidate and evaluate any physical signs associated with a particular pain condition.

To reassure the patient that pain does not imply any ongoing damage.

To reassure the patient that pain does not imply any ongoing damage.

To define baseline parameters and monitor their change over time.

To define baseline parameters and monitor their change over time.

To understand the mechanisms that sustain the pain, in particular to identify neuropathic elements.

To understand the mechanisms that sustain the pain, in particular to identify neuropathic elements.

Investigation

Investigation of a patient in pain is individually structured. It serves three important goals:

Measuring pain

Multidimensional (complex) scales

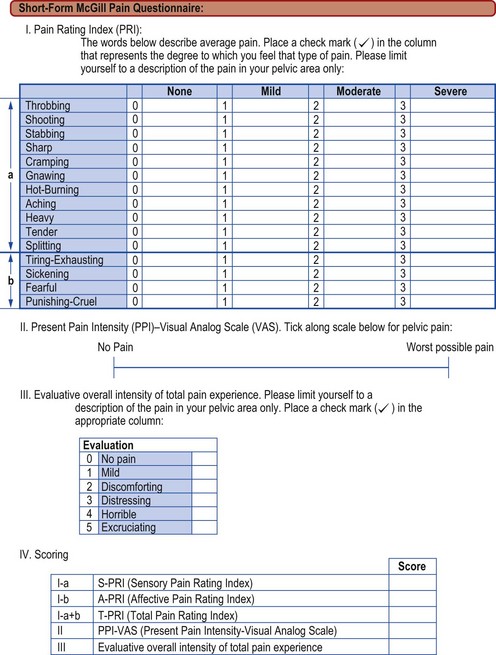

The development of multidimensional scales acknowledges the multidimensional impact of pain on an individual’s life. The most frequently employed scale in use is the McGill Questionnaire. There are two forms of this: the original McGill Questionnaire assesses various aspects of pain, including sensory qualities of pain, affective qualities (tension, fear, etc.) and evaluative words that describe the subjective intensity of the total pain experienced. There are various measurements derived from the data, but a short form of the McGill Questionnaire is most used (Fig. 9.2). It is easy to apply and reproducible.

Treatment strategies

Treatment options

Pharmacology

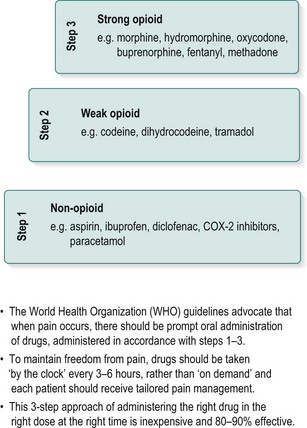

Pharmacological options include simple analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids and non-conventional analgesics. These are prescribed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder (Fig. 9.3). This is generally effective in acute pain and in most cases of cancer pain. However, in chronic pain, drugs are less effective and there is often a neuropathic component. For neuropathic pain, the most commonly used drugs are antidepressants and anticonvulsants.