28 Patient preparation and principles of sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy

Case

A 67-year-old male with a past history of mitral valve stenosis and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitis with moderate renal impairment requests his primary care physician to organise colon cancer screening. An open-access colonoscopy is arranged.

Introduction

This chapter deals with several of the most important aspects of providing a safe endoscopic practice: preprocedure patient assessment, management of anticoagulation, antibiotic prophylaxis and intraprocedural sedation.

Preparing Patients for Endoscopy

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Patients undergoing ERCP will be exposed to ionising radiation. Therefore women of childbearing age should have pelvic shielding during the procedure. If there is any possibility of pregnancy a serum or urinary β-human chorionic gonadotropin should be checked. Contrast medium in the bowel lumen can obstruct views of the biliary system, so patients who have recently had a CT scan with contrast or a barium study should have a plain abdominal x-ray to ensure the biliary system is not obscured. As iodinated contrast is used to inject into the biliary system, a history of iodine allergy or hyperthyroidism should be elicited, though history of a contrast allergy is not an absolute contraindication as the risk of an allergic reaction during ERCP is extremely low. Patients with biliary obstruction should receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to the procedure. Due to the risk of bleeding with sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater, elective patients on clopidogrel should ideally withhold this medication for 7–10 days if feasible. The risk is lower with aspirin (all therapeutic endoscopy can be performed on aspirin). Discussion with the patient’s cardiologist is prudent if there is uncertainty whether it is safe to withhold these medications. Coagulopathy should be reversed if present; patients on warfarin may need to change to low-molecular-weight heparin prior to the procedure depending upon the indication. The decision when to reinstitute anticoagulant therapy following therapeutic procedures such as ERCP and colonic polypectomy is a difficult one and should be individualised in consultation with the patient’s cardiologist.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Advice regarding antibiotic prophylaxis prior to endoscopic procedures was significantly updated in American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines (2008) based on the recognition from the American Heart Association that bacterial endocarditis from endoscopic procedures was exceedingly rare. For the majority of patients undergoing endoscopic procedures, including those with prosthetic heart valves or congenital cardiac abnormalities, antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent bacterial seeding was no longer recommended. There are however, certain situations in which the risk of infective complications (which may be local rather than systemic) is increased and antibiotics are warranted; these are listed in Box 28.1.

Box 28.1 Antibiotic prophylaxis for endoscopy

All patients prior to insertion of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

All patients with cirrhosis with acute GI bleeding (intravenous ceftriaxone from admission)

Disease-specific issues

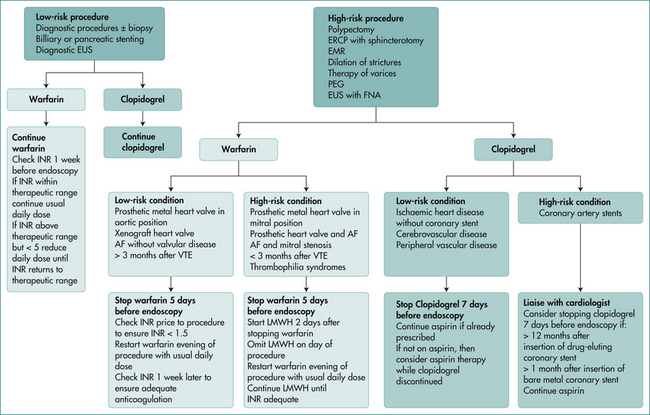

Patients can take their normal medications several hours prior to the procedure with a sip of water. The management of patients taking antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants is a complex issue, and should be in accordance with published guidelines. These guidelines take into account whether the procedure is elective or an emergency procedure, the indication for the antiplatelet agent or anticoagulant, and the bleeding risk related to the procedure. A suggested algorithm for management of patients requiring anticoagulation is outlined in Figure 28.1.

The management of patients with diabetes mellitus will depend upon whether they have type 1 or type 2 diabetes, and on whether they are diet-controlled or on diabetic medications or insulin. Patients with type 2 diabetes are more easily managed as they can generally withhold their medications or insulin on the morning of the procedure. If undertaking bowel preparation on the previous day, similar withholding or reduction in dosage is appropriate. For type 1 diabetes the management is more complicated as some maintenance insulin is required in order to avoid the risk of precipitating ketoacidosis. Involvement of the patient’s diabetic specialist may be useful, and in some situations admission to hospital early on the day of the procedure or even the night before the procedure for an insulin/dextrose infusion may be appropriate. Diabetic patients should be first on elective morning endoscopy lists in order to minimise fasting and disruption of glycaemic control.

Principles of Anaesthesia for Endoscopy

Introduction

The aim of anaesthesia is to provide a comfortable experience for the patient during the procedure, and to keep the patient still to enable the procedure to be performed. Sedation can be divided into different categories according to the depth of sedation. The American Society of Anaesthesiologists provides the following categorisation (see Table 28.1). The term ‘moderate sedation’ is being increasingly used instead of the potentially confusing term ‘conscious sedation’. Note that patients can move between different sedation states quickly, and proceduralists targeting a level of sedation should be competent at managing patients who enter the next deeper level of sedation. Assessment of the depth of sedation can be difficult as there is no widely accepted objective measure of the depth of sedation. A study of 80 patients sedated for endoscopy with the view to moderate sedation with midazolam and meperidine (pethidine) showed that 68% of patients entered a period of deep sedation at some point during their procedure.

Table 28.1 Clinical states of sedation (American Society of Anaesthesiologists)

| Sedation level | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Minimal sedation | Normal response to verbal stimulation. |

| Moderate sedation | Purposeful response to verbal or tactile stimulation. Spontaneous ventilation is adequate and no airway intervention is required. |

| Deep sedation | Purposeful response only after repeated or painful stimulation. Spontaneous ventilation may be inadequate, and airway intervention may be required. |

| General anaesthesia | Unrousable, even with painful stimuli. Airway intervention is often required and spontaneous breathing is usually inadequate. Cardiovascular compromise may occur. |

Patient assessment

A useful guide for assessing anaesthetic risk has been developed by the American Society for Anaesthesiology (Table 28.2). Patients with an ASA status greater than III should be managed by an anaesthetist.

Table 28.2 American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) classification of anaesthetic risk

| Class | |

|---|---|

| I | The patient is normal and healthy |

| II | Mild systemic disease that does not limit activity (e.g. controlled hypertension) |

| III | Moderate or severe systemic disease that does not limit activity (e.g. stable angina, diabetes mellitus with systemic sequelae) |

| IV | Severe systemic disease that is a ‘constant threat to life’ (e.g. end-stage renal failure, severe cardiac failure) |

| V | Patient is morbid and at substantial risk of death within 24 hours (whether the procedure is performed or not) |

| E | Emergency status: add this as a suffix for emergency cases (e.g. IIIE) |

Patients who should be sedated by an anaesthetist

There is a group of patients in whom the risks of sedation are significantly increased, and for whom it is more appropriate for an anaesthetist to deliver sedation. This includes patients with severe comorbidities such as cardiac, pulmonary or renal disease who have an ASA grading over III (see Table 28.2). In addition, patients with abnormalities of the oropharynx, neck or airway are at increased risk of airway problems if oversedation occurs (see Box 28.2). Patients at extremes of age, who abuse alcohol or other drugs, are pregnant or who are planned for a procedure of long duration or in which deep sedation is required are also suitable to be referred to an anaesthetist. In addition, those with a high risk of having a large residual gastric content such as patients with a small bowel obstruction should be managed by an anaesthetist due to the increased risk of aspiration.

Logistics of administering sedation

The logistics of administering sedation are very important, and if performed inadequately can create an unsafe situation with significant potential of an adverse event occurring. These issues include monitoring of the patient during and after the procedure, administration of anaesthetic agents, training and level of staffing, and protocols for managing emergencies. Communication between the proceduralist and nursing staff is critical in order to clearly communicate orders relating to sedation, and also to feed back to the proceduralist changes in the patient’s status that require attention. All staff should feel comfortable vocalising concerns about a patient’s status if they feel that the safety of a patient has been compromised, and not feel that doing so is inappropriate due to issues of hierarchy or seniority.

Monitoring of patients

Capnography

Although pulse oximetry provides some indication of when hypoxia has occurred, it is a relatively blunt tool to detect hypoventilation and apnoea, which can be further masked by the use of supplemental oxygen. An excellent way to monitor for hypoventilation is to use non-invasive capnography, which measures CO2 concentration in the vicinity of expired air. This is graphically represented as an oscillating line as the patient breathes in and out and the CO2 concentration changes. The actual CO2 level estimated is not critical. Rather, capnography demonstrates in real time that the patient is breathing. Capnography enables hypoventilation and apnoea to be detected immediately as reflected by a lack of oscillation in expired carbon dioxide (CO2). A capnograph probe can be used attached to a Hudson mask, and even attached to nasal prongs.

Medications used in sedation

Propofol

Propofol is an anaesthetic agent that acts by causing the release of gamma amino butyric acid in the brain. It is increasingly used in endoscopy due to its attractive properties such as rapid onset and offset, shortened recovery time, and fewer effects on neuropsychiatric functioning postprocedure. The half-life is 1–4 minutes, and the onset of sedation is within 30–60 seconds. Propofol is regarded as having a ‘narrow therapeutic window’ that can result in rapid depression to deep sedation or even general anaesthesia. In addition, hypotension can occur due to decreased systemic vascular resistance and negative cardiac inotropy. It has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use by anaesthetists, but it is commonly used ‘off label’ by endoscopists for sedation. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials comparing propofol use during endoscopy to combined midazolam and opiates suggested that there were no differences in hypoxaemia, hypotension, the proportion of patients reporting pain or physician satisfaction, though patient satisfaction was higher in the propofol group. Furthermore, in contrast to benzodiazepines and narcotics there is no reversal agent. This means that a practitioner using propofol must be prepared to artificially ventilate an apnoeic patient for up to several minutes if necessary.

Management of oversedation

Staffing

The level of staffing depends upon the procedure being performed, but should ideally include a nurse to assist with the procedure such as the use of biopsy forceps, and a nurse allocated to monitor the patient and administer sedation. Training of staff with regard to the principles behind the use of sedative agents and management of oversedation is important, and regular training or education sessions should be attended. There should be at least one practitioner who has advanced resuscitation skills (such as endotracheal intubation, defibrillation and usage of resuscitation medications) available within 1–5 minutes. If propofol is used, a practitioner with experience in advanced life support should be dedicated solely to sedation and patient monitoring. Recently, the Australia and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Gastroenterology Society of Australia and Royal Australian College of Surgeons have prepared a statement on appropriate staffing for different patient settings and anaesthetic agents. A regularly checked resuscitation trolley or kit should be available with equipment for endotracheal intubation, and a defibrillator should be available within several minutes. However, the vast majority of adverse events are related to oversedation and will respond promptly to bag and mask ventilation.

Key Points

[Anonymous]. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):1004-1017.

Australia and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Gastroenterology Society of Australia and Royal Australian College of Surgeons. PS9: guidelines on sedation and/or analgesia for diagnostic and interventional medical or surgical procedures, February 2008. Online.

Banerjee S., Shen B., Baron T.H., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(6):791-798.

Burton J.H., Harrah J.D., Germann C.A., et al. Does end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring detect respiratory events prior to current sedation monitoring practices? Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13(5):500-504.

Carbonell N., Pauwels A., Serfaty L., et al. Erythromycin infusion prior to endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(6):1211-1215.

Cohen L.B., DeLegge M.H., Aisenberg J., et al. AGA Institute review of endoscopic sedation. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):675-701.

Eisen G.M., Baron T.H., Dominitz J.A., et al. Guideline on the management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy for endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(7):775-779.

Evans L.T., Saberi S., Kim H.M., et al. Pharyngeal anesthesia during sedated EGDs: is ‘the spray’ beneficial? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(6):761-766.

Ladas S.D., Aabakken L., Rey J.F., et al. Use of sedation for routine diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy survey of McQuaid KR, Laine L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2008;67(6):910-923.

National Endoscopy Society members. Digestion. 2006;74(2):69-77.

Patel S., Vargo J.J., Khandwala F., et al. Deep sedation occurs frequently during elective endoscopy with meperidine and midazolam. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(12):2689-2695.

Rex D.K. Review article: moderate sedation for endoscopy: sedation regimens for non-anaesthesiologists. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;24(2):163-171.

Robin C., Trieger N. Paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines in intravenous sedation: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Anesth Prog. 2002;49(4):128-132.

Sorbi D., Gostout C.J., Henry J., et al. Unsedated small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus conventional EGD: a comparative study. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(6):1301-1307.

Vargo J.J., Zuccaro G.Jr., Dumot J.A., et al. Automated graphic assessment of respiratory activity is superior to pulse oximetry and visual assessment for the detection of early respiratory depression during therapeutic upper endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(7):826-831.

Veitch A.M., Baglin T.P., Gershlick A.H., et al. Guidelines for the management of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gut. 2008;57(9):1322-1329.