Patient positioning: Common pitfalls, neuropathies, and other problems

Upper-extremity neuropathies

Ulnar neuropathy

Ulnar neuropathy is the most common perioperative neuropathy.

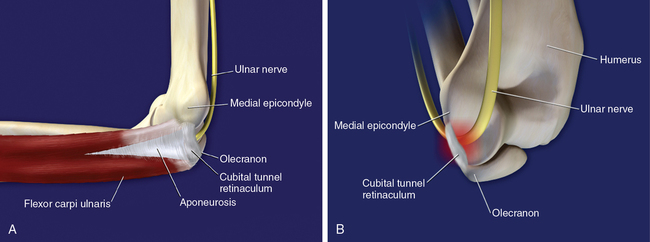

Anatomy and elbow flexion

Prolonged elbow flexion of more than 90 degrees increases intrinsic pressure on the nerve and may be as important an etiologic factor as is prolonged extrinsic pressure. The ulnar nerve passes behind the medial epicondyle and then runs under the aponeurosis that holds the two muscle bodies of the flexor carpi ulnaris together. The proximal edge of this aponeurosis is sufficiently thick, especially in men, to be separately named the cubital tunnel retinaculum. This retinaculum stretches from the medial epicondyle to the olecranon. Flexion of the elbow stretches the retinaculum and generates high pressures intrinsically on the nerve as it passes underneath the retinaculum (Figure 244-1).

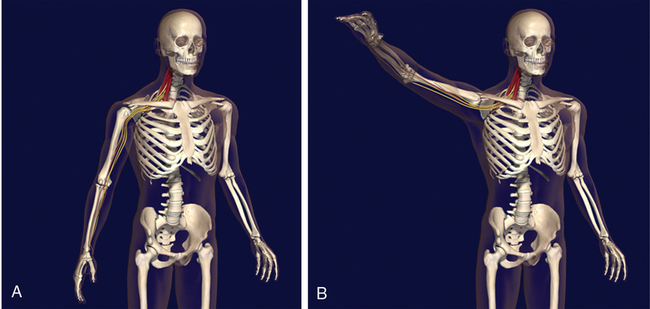

Brachial plexopathies

Anatomy of shoulder abduction

Abduction of a shoulder of 90 degrees or more places the distal plexus on the extensor side of the joint and potentially stretches the plexus (Figure 244-2). Therefore, it is prudent to avoid abduction of more than 90 degrees, especially for extended periods of time.

Lower-extremity neuropathies

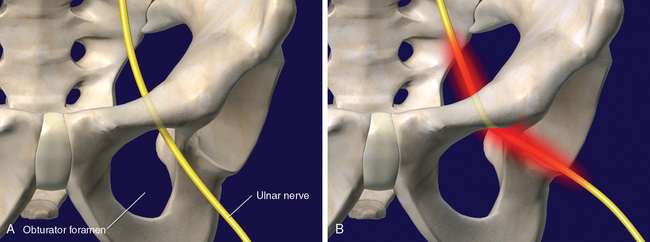

Impact of hip abduction on the obturator nerve

Hip abduction of more than 30 degrees results in significant strain on the obturator nerve. The nerve passes through the pelvis and out the obturator foramen. With hip abduction, the superior and lateral rim of the foramen serves as a fulcrum (Figure 244-3). The nerve stretches along its full length and is also compressed at this fulcrum point. Thus, excessive hip abduction should be avoided whenever possible. With obturator neuropathy, motor dysfunction is common, and approximately 50% of patients who have motor dysfunction in the perioperative period will continue to have it 2 years later. The dysfunction is usually not painful, but it can be debilitating.

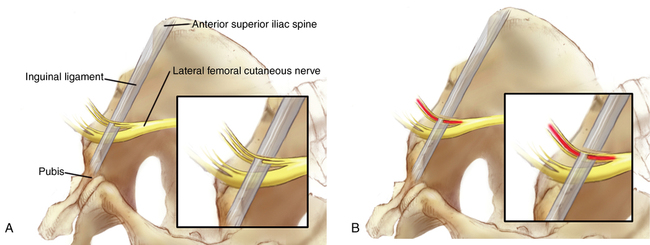

Impact of hip flexion on the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

Prolonged hip flexion of more than 90 degrees increases ischemia on fibers of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. One third of the fibers of this nerve pass through the inguinal ligament as the fibers pass into the thigh (Figure 244-4). Hip flexion of more than 90 degrees results in lateral displacement of the anterior superior iliac spine and in stretch of the inguinal ligament. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is compressed by the stretched inguinal ligament and, with time, becomes ischemic and dysfunctional. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve carries only sensory fibers, so no motor disability occurs when this nerve is injured. However, patients with this perioperative neuropathy can have disabling pain and dysesthesias of the lateral thigh. Approximately 40% of these patients have dysesthesias that last for more than a year.