28 Patient education and care of the perianesthesia patient

Affective Learning: Relates to attitude and includes the ability to receive, respond, value, and organize a personal value system and internalize the value system.

Cognitive Learning: The human processing of information; application of knowledge.

Continuous Positive-Pressure Airway (CPAP): Delivers air into the patient’s airway and creates enough pressure to keep the airway open during inhalation.

Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (IMV): Allows patients to breathe on their own as often and as deeply as they like and ensures that a set tidal volume is delivered at a predetermined back-up rate.

Patient Education: Useful information that helps patients and their families or companions become more informed about the medical and nursing care they receive before, during, and after surgical and diagnostic procedures.

Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP): A technique that can be used to help prevent collapse of the alveoli during the expiratory phase of ventilation, to increase the lung’s functional residual capacity, and to reduce the amount of physiologic shunting.

Stir-Up Regimen: Consists of five major activities as the patient is recovering from anesthesia: deep-breathing exercises, coughing, positioning, mobilization, and pain management.

Sustained Maximal Inspiratory (SMI) Maneuver: The patient inhales as close to total lung capacity as possible and, at the peak of inspiration, holds that volume of air in the lungs for 3 to 5 seconds before exhaling.

Synchronous Intermittent Mandatory Ventilation (SIMV): Allows the patient to control the inspiratory time and the size of the spontaneous tidal volumes.

Patient education concepts and perianesthesia care

The purpose of preoperative education is to empower patients, give them greater decision-making authority related to their care, and enable them to better manage their health. The patient benefits from learning before the surgery with decreased preoperative fear and anxiety, postoperative complications, recovery time, and postoperative pain.1,2 Education also increases patient compliance with instructions and improves coping mechanisms for the patient and preparation. Preoperative education is for the patient and the family or companion and is a responsibility of the professional registered nurse.

Before providing education for patients, perianesthesia nurses complete a self-assessment that reflects on strengths and weaknesses such as knowledge base, understanding of the information to teach, and whether they like or dislike teaching. Consideration should be given to personal biases: does the nurse react negatively to patients with a history of alcohol use or who are obese? Does the nurse dislike children or the elderly? Do the religious or ethnic preferences of the nurse conflict with the patient population served? Sensitivity to diversity and cultural awareness of patients improve the professional registered nurse’s ability to provide appropriate education for the patients and families or companions. The nurse may need to work on improving knowledge and teaching skills while preventing biases from affecting the duty to provide patient education.

Learning environment and learning needs

Methods for identifying learning needs of the patient and the family or companions include asking open-ended questions, directly observing the patient and family, and hearing the verbal cues that indicate learning and knowledge. Nonverbal cues are also observed and noted. The patient’s and family’s or companion’s current knowledge level can be identified through questionnaires, telephone conversations, observation, or interview. Patient education is more effective when the content and methods are individualized for the patient and family; the nurse should determine what the patient and family or companion want and need to know and teach them accordingly.1

Types of learners

When a child is the patient, the parents often begin education at home, depending on the age of the child and the preparation needed. Therefore parent preparation is essential and requires knowledge of adult learning characteristics by the nurse. Typically the younger the child, the closer to the day of the procedure the education occurs. Parents’ and caregivers’ understanding of the child’s behavior and developmental stage should guide the nurse in choosing appropriate teaching tools and techniques. Even with preparation, separation anxiety for both child and parent occurs and may be especially difficult for the 1- to 5-year-old child. See also Chapter 49 for specific information about caring for the pediatric patient.

The older adult may have had less formal education, and comprehension may be limited. However, the learning challenges of older patients may be related to sensory deficiencies that can interfere with the ability to learn, and not educational level or intellect. Chapter 50 reviews the care of the geriatric patient and the specific challenges of this population.

Influences on learning

Physiologic, emotional, cultural, and environmental barriers can hinder the learning process for all ages and developmental levels.1 Language barriers can decrease the patient’s ability to understand instructions and limit compliance with instructions because of a lack of comprehension. Inadequate or poor teaching can also be a barrier to the learning process, and the professional registered nurse works on improving knowledge and skills of teaching and learning for the patient populations encountered. Another consideration is evaluation of the learner’s present knowledge, previous experience, prior education, perceptions, expectations, and potential misinformation. The patient’s health beliefs, attitudes, level of stress, coping skills, anxiety, and social support also influence learning.

Teaching characteristics and planning

The professional registered nurse needs to have knowledge of teaching-learning principles, to recognize that anxiety and pain impede learning, and to value reinforcement of learning. Common language, not medical terminology, should be used. Knowledge of the teaching tools available and the content to teach is essential for successful patient education.

Content of teaching plan

The teaching plan includes generic content, with general information about preoperative preparation, day of surgery activities, and postoperative issues. The environment is described, as is the usual sequence of events. Individualized content is also integrated into the teaching plan to meet needs identified by the nurse’s assessment of learning, review of the patient’s history, and information requested by the patient or family.1

Discussion related to possible alterations in comfort helps to prepare the patient for what to expect after surgery. Common concerns include pain, sore throat, nausea, and vomiting. The patient’s past experience may influence expectations. Descriptions of strategies for pain reduction, including request of pain medication and use of positioning, ice, or other techniques, may ease the patient’s concerns about pain and discomfort. Postoperative nausea and vomiting may be minimized or controlled with medications, aromatherapy, hydration, and slow movements. Additional information on pain management can be found in Chapter 31; nausea and vomiting are discussed in Chapter 29.

Teaching strategies

The nurse’s primary objectives when teaching are establishing a rapport to reduce anxiety and fear, assessing patient and family knowledge and expectations for learning, and assessing patient and family learning style to enhance the learning process. These objectives can apply to teaching before the day of surgery in a structured setting, patient education that occurs at the bedside while the patient is in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), or teaching during preparation for discharge. The level of detail provided should be based on these assessments, with the education tailored specifically to the patient and family or companion. Teaching should be directed to the patient, but the family decision-maker or primary caregiver should also be considered as important to educational success. Ample opportunity for the patient and family to voice concerns and ask questions should be provided. If language is a barrier, interpreter services can assist in the teaching process. Short simple explanations are best, with the importance of the instructions and expected benefits of compliance with the instructions stressed. Jargon should be avoided and all terms should be clarified. Teachable moments should be used to take advantage of times when the patient and family are most likely to accept new information (e.g., symptoms are present).

Documentation

Patient education completed by the nurse is documented as a record of education provided to the patient. Forms vary by institution and may be paper or electronic. Standardized care plans include documentation of individualized education. Checklists or flow sheets may be used. Whatever the form, teaching should be documented to support the work of the nurse and record what the patient was told and the response to the educational information. This documentation protects the patient, the nurse, and the facility should concerns arise over educational content and patient preparation. Additional information on documentation can be found in Chapter 7.

Care of the perianesthesia patient

Stir-up regimen

Coughing

Preoperative teaching of postoperative breathing exercises and coughs and their importance is effective and should be included in the preoperative regimen whenever possible. Patients scheduled for surgery may attend formal teaching sessions before surgery or may receive instructions for coughing, deep breathing, and incentive spirometry through educational booklets, video programs, and visits to preoperative testing departments.

Pain management

Achievement of the stir-up regimen’s first four activities is difficult if adequate pain relief is not provided. Opioids depress the cough reflex and ciliary action and may lower alveolar ventilation with direct depression of the respiratory center. If breathing is painful and splinting occurs or if the patient refuses to cough or move because of pain, respiratory or embolic complications can occur. Pain management is discussed in detail in Chapter 31.

Intravenous therapy

Postoperative parenteral fluid requirements vary with the patient’s preoperative status and with the surgical procedure. For a discussion of fluid and electrolyte imbalance, see Chapter 14.

Maintenance of respiratory function

Oxygen therapy

Pulse oximetry, a noninvasive technique, is used to measure arterial oxygen saturation of functional hemoglobin. In the postanesthesia setting, continuous monitoring of a patient’s oxygen saturation assists in manipulation of the fraction of delivered oxygen (FDO2) levels and in identification of episodes of desaturation and hypoxemia.3 Normal pulse oximetry values are 97% to 100%. Oxygen saturation as measured with pulse oximetry (SpO2) values of 95% or greater are acceptable. Preanesthetic baseline SpO2 values should be noted; patient levels may normally fall below the normal range in room air. Attempts to maintain higher oxygen saturation levels than the baseline level can result in prolonged oxygen therapy and PACU stays.

Source: Pedersen T, et al: Pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4 (CD002013):2009.

Nurses may need to draw arterial blood gases to aid in the assessment of a patient’s status. For discussion of arterial blood gases and the method for measurement, see Chapter 12.

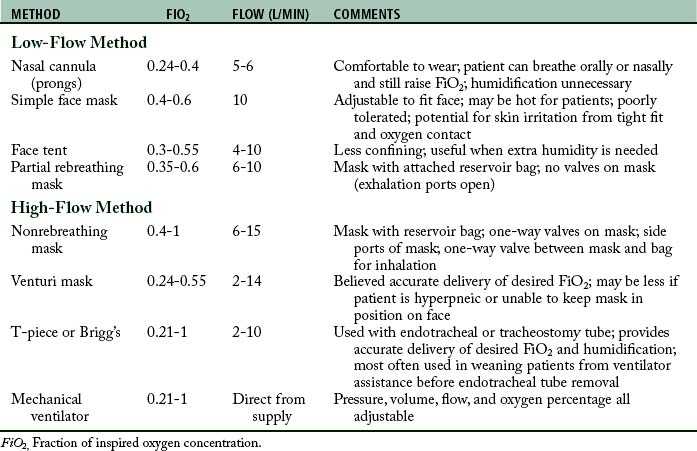

Methods of administration

Routine oxygen administration in the PACU can be accomplished with nasal cannula (prongs) or face masks. Table 28-1 lists commonly used oxygen delivery methods. Nasal cannulas are advantageous for routine short-term oxygen administration in the PACU. The cannula is made of plastic tubing with two soft plastic tips that insert into the nostrils about 1.5 cm. The prongs deliver 100% oxygen and thus yield a final inspired oxygen concentration of approximately 30% to 40% when a flow of 4 to 6 L/min is used. The prongs are easily inserted, comfortable, inexpensive, and disposable. Simple clear plastic disposable face masks can be used for oxygen administration in the PACU. They are also easy to apply and comfortable. The oxygen concentration inspired depends on the mask fit and the patient’s inspiratory flow rate; however, an oxygen flow rate of 10 L/min yields an FiO2 of up to 60%. A higher flow rate keeps the patient from rebreathing exhaled carbon dioxide (CO2). Face masks in the PACU must be clear to provide adequate observation of the patient’s nose and mouth. The mask should be removed intermittently to dry the face.

Capnography

Capnography is used to measure ventilatory status at the end of expiration thereby measuring the adequacy of ventilation at the alveolar level. End-tidal carbon dioxide can be measured via an endotracheal tube or via a sensor as part of a nasal cannula that also delivers oxygen. A patient in the PACU may require assessment of ventilatory status with the use of capnography. See Chapter 27 for a detailed discussion of capnography.

Mechanical ventilation

Rarely, some patients who are recovering from anesthesia may need some form of mechanical ventilation in the PACU. Various techniques such as positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) are used to improve the respiratory status of the patient. Table 28-2 gives the terminology of the common ventilatory modes.

| ABBREVIATION | TERM |

|---|---|

| Mechanical Ventilation with Positive Airway Pressure | |

| A/C | Assist–control ventilation |

| CMV | Continuous mandatory ventilation |

| IMV | Intermittent mandatory ventilation |

| SIMV | Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation |

| PSV | Pressure support ventilation |

| PEEP | Positive end-expiratory pressure |

| APRV | Airway pressure-release ventilation |

| Spontaneous Breathing with Positive Airway Pressure | |

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| BiPAP | Bilevel positive airway pressure |

Positive end-expiratory pressure

When a patient receives PEEP therapy, hemodynamic status should be monitored because this ventilatory technique decreases venous return and may cause a decrease in cardiac output, especially in the patient with hypovolemia. In some instances, the reduced cardiac output can cause a decrease in systolic blood pressure. Other parameters to be monitored are vital signs, skin perfusion, and urine output.

Nursing responsibilities

All PACU nurses must be familiar with the specific types and modes of operation of ventilators used in the area (Fig. 28-1; see Table 28-2); however, some nursing responsibilities remain the same regardless of mechanical ventilator. The following list discusses these responsibilities.

1. Ascertain that the patient’s lungs are ventilated with frequent observation of the chest for bilateral synchronous and equal expansion and by listening for bilaterally present and equal breath sounds.

2. Check the airway frequently for complete patency. See that the patient’s ventilator system is free of significant leaks by listening for air gurgling in the upper airway during ventilation and by comparing the exhaled volume with the tidal volume set on the ventilator.

3. Ensure that the cuff is never overinflated. Inflate the cuff until no leak is identified on tidal ventilation and a small barely audible leak occurs on sigh volume.

4. Empty the ventilatory hoses frequently of excess water from condensation.

5. Ensure that proper humidification is delivered to the patient by noting the presence of water droplets in the ventilator hoses.

6. Check the humidifier and fill frequently to ensure proper humidification.

7. Ensure that the temperature gauge is between 32.2° and 36.6° C, and that the ventilator hoses and humidifier are warm to the touch and never cold or hot.

8. Position the patient’s endotracheal or tracheostomy tube so that there is never any pull.

9. Perform the tracheostomy wound care as needed during the postanesthesia phase.

10. Ascertain frequently that all alarms on the ventilator are on, set appropriately, and functioning properly.

Suctioning

Tracheal suctioning

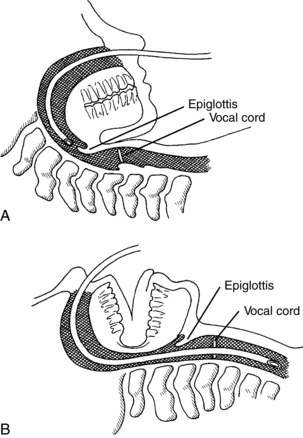

Tracheal suctioning can be performed through the mouth or nose, via endotracheal tube, or through a tracheostomy tube (Fig. 28-2). Tracheal suctioning must be accomplished atraumatically with aseptic technique. A selection of sterile suctioning catheters in a variety of sizes should be kept at the bedside of every patient in the PACU along with sterile gloves and sterile water or normal saline solution. The catheter chosen for suctioning should not have an external diameter that exceeds by one third the internal diameter of the tube to be suctioned. Most commonly, a 14 or 16 F size is used for adult patients. The catheter must not completely occlude the trachea or endotracheal tube.

Before suctioning, ensure proper ventilation. In most patients, suctioning lowers the arterial pressure of oxygen 30 to 35 mm Hg. Because suctioning removes oxygen, which can in turn initiate cardiac dysrhythmias, the nurse should assess the total physiologic condition of the patient before beginning the procedure. Is the patient restless, agitated, or disoriented? Although these conditions can be caused by other factors, they often indicate inadequate oxygenation. Conscious patients should be asked to take four or five deep breaths. The patient who cannot cooperate must undergo preoxygenation with a bag-mask unit or anesthesia bag. A bag-mask device delivers variable oxygen concentrations (FiO2 between 30% and 95%) and volumes. Flow rates should be at least 10 to 15 L/min for higher FiO2. Higher volumes can be obtained with the use of two hands to compress the bag. If the patient has an endotracheal airway in place and is using a ventilator, several sigh volumes can be delivered at 1 FiO2 before suctioning.

General comfort and safety measures

General comfort and safety measures are important parts of postanesthesia care. For safety, at least two nurses (one of whom is a registered nurse competent in phase I perianesthesia nursing care) should always be present in the same room or unit whenever patients in PACU Phase I level of care are recovering.4 An unconscious patient should never be left alone, and side rails should be raised on the bed or stretcher whenever direct patient care is not being provided. The wheels of the bed or stretcher should be locked to prevent sliding when care is rendered.

Mouth care with moistened Toothettes or swabs may be comforting to the patient who has been without oral fluids or breathing dry gases. When patients are fully conscious and laryngeal reflexes have returned, they can rinse the mouth with water. Ice chips and small sips of water or juice can be offered to the patient who can tolerate fluids. Ointment should be applied to the lips after mouth care to prevent drying and consequent cracking.

Patients often are cold when they return from the operating suite. This condition is caused in part by the effects of anesthesia and the cool atmosphere of the operating suite and the PACU. These reasons must be explained to the patient. Active warming measures, such as a convective warming device, should be instituted on arrival to the PACU if the patient is hypothermic.5 Devices should be used according to the manufacturers’ recommendations to avoid patient injury.

The patient who is normothermic may shiver or feel cold; warm blankets may provide psychologic comfort, and active warming interventions may be needed to reduce or eliminate shaking. Blankets of any type should not, however, obscure the intravenous lines, arterial lines, or other monitoring apparatuses from the direct view of the attending nurse. The patient’s body temperature must be monitored closely to avoid overheating. Shivering may be treated with low doses of meperidine, 12.5 to 25 mg intravenously, which attenuates the shivering response. Hypothermia is discussed in Chapter 53.

Transfer of the patient from the postanesthesia care unit

Patients can be transferred on a stretcher or bed as required by condition and operative procedure. The patient should be adequately covered with bed linens, including a warmed blanket if hallways are kept cool. The side rails of the stretcher should be locked in place. Ideally, two persons should wheel the stretcher to the receiving unit. Transport personnel vary by institution, and decisions regarding who transports can vary based on the patient’s condition, staffing, and unit needs. Practice Recommendation 6, in the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses’ 2010-2012 Perianesthesia Nursing Standards and Practice Recommendations, address required elements for the safe transfer of care.4 The handoff between providers should allow communication of patient status and care needs; the opportunity to ask questions of the transferring caregiver is required. The form of that transfer varies by facility policy and practice, but must minimize patient risk.

A receiving nurse should meet the patient on arrival to the unit and direct the transfer to the patient’s room. The patient is transferred to the bed along with all apparatuses. Safety precautions must be strictly followed. At least two people should always transfer the patient. A third person may be necessary to assist with the patient transfer if extra equipment or multiple drainage tubes are present. Use of transfer devices such as slider boards, roller tubes, or mechanical lifts facilitates the transfer and minimizes the risk of injury for both the patient and the nursing staff. Both the bed and the stretcher should be stabilized by locking the wheels when transferring the patient from one to the other. The nurse should ensure that all drainage tubes and catheters are safely transferred, that no kinking occurs, and that they do not become tangled underneath the patient. All drainage receptacles should remain below the level of the patient. Intravenous tubing and solution must be carefully transferred from the portable stand attached to the stretcher to the bedside stand or holder. Drainage tubes should be connected to suction or gravity drainage as indicated, and their proper functioning checked. The patient’s call light should be positioned within the patient’s reach, along with any other items that may be needed. The intravenous infusion rate should be assessed and adjusted as necessary. Side rails on the bed should be raised.

Summary

This chapter discussed patient education concepts including learner characteristics and teaching strategies. Nursing care of postanesthesia patients who are emerging from anesthesia is also reviewed in this chapter. Postanesthesia care discussed included the stir-up regimen, intravenous therapy, maintenance of cardiopulmonary function, and general comfort measures.

1. Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Adult surgical patients and the information provided to them by nurses: a literature review. Patient Educ Couns.2006;61(1):5–15.

2. Fredericks S, et al. Postoperative patient education: a systematic review. Clin Nurs Res.2010;19(2):144–164.

3. Pedersen T, et al. Pulse oximetry for perioperative monitoring. (CD 002013). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4. 10.1002/14651858.CD002013.pub2. Accessed December 6, 2011

4. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN): Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations 2010–2012. Cherry Hill, NJ: ASPAN; 2010.

5. Hooper VD, et al. ASPAN’s evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the promotion of perioperative normothermia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2009;24(5):271–287.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses: AACN procedure manual for critical care. ed 6. St. Louis: Saunders; 2011.

Black JM, Hawks JH. Medical-surgical nursing: clinical management for positive outcomes. ed 8. St. Louis: Saunders; 2008.

Finucane BT, et al. Principles of airway management, ed 4. New York: Springer; 2011.

Godden B. Where does capnography fit into the PACU. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26(6):408–410.

Johansson K, et al. Surgical patient education: assessing the interventions and exploring the outcomes from experimental and quasiexperimental studies from 1990 to 2003. Clin Effectiveness Nurs.2004;8(2):81–92.

Pasquina P, et al. Respiratory physiotherapy to prevent pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Chest.2006;130(6):1887–1899.

Sjoling M, et al. The impact of preoperative information on state anxiety, postoperative pain and satisfaction with pain management,. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:169–176.

Stern C, Lockwood C. Knowledge retention from preoperative patient information. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2005;3:45–63. 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2005.00021.x. Accessed December 6, 2011

Zhang CY, et al. Impact of nurse-initiated preoperative education on postoperative anxiety symptoms and complications after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27(1):84–88.