Chapter 14

Patient Clinical Evaluation

Philip P. Goodney

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by G. Matthew Longo and Thomas G. Lynch

The emphasis of this chapter is on the use of the history and physical examination to identify the various disease states associated with arterial, venous, and lymphatic pathology. In general, the lower extremities provide a model for the clinical evaluation of patients with peripheral vascular disease and can be used to demonstrate the value of an organized approach to the history and physical examination. When appropriate, correlation will also be made with related pathology and symptoms in the upper extremities.

Overview

First, the patient’s chief complaint should be determined; the physical examination should be correlated with the history and should also provide a bridge to the pathophysiology of the disease process.1,2 As an example, aortoiliac obstructive disease will often be associated with more proximal symptoms of claudication involving the buttock, hip, or thigh. If the clinical history is accurate, the examiner should expect that the femoral pulse will be absent or decreased. If the history is not accurate, the history and assumptions regarding pathophysiology should be questioned.

When the history and physical examination are completed, diagnostic studies can be ordered, if necessary, to further localize the disease or quantify the extent of the process. Therapy is ultimately driven by the natural history of the disease process and its impact on quality of life, as well as by the patient’s risk factors and functional status. A relatively benign natural history or significant and unmodified patient risk factors may indicate an initial course of medical management, risk factor modification, and observation, whereas threat of tissue loss may indicate a need for more aggressive intervention.

Evaluation begins with identifying the patient’s signs and symptoms. It is important to obtain a chronologic description of the development and progression of the patient’s main complaint from the first sign or symptom to the present.

Clinical History

Typically, the symptoms of arterial and venous disease can be broadly classified into the following categories: pain; weakness; neurosensory complaints, including warmth, coolness, numbness, and hypersensitivity; discoloration; swelling; tissue loss and ulceration; and varicosities. Critical elements include the initial onset of symptoms (acute or chronic); progression or changes since the initial onset; location (unilateral, bilateral, proximal, distal); character or quality of the symptom or complaint; some measure of the extent of disability or limitation; the context or factors precipitating or aggravating the symptoms (activity, position, temperature, menses, vibration, pressure); factors mitigating or relieving symptoms; and associated signs, symptoms, or risk factors. In the assessment of vascular disease, the history is important. As will be seen, variations from the expected history or pattern of findings may suggest additional disease processes that may be included in the differential diagnosis.

As part of the history, associated vascular disease and predisposing risk factors should also be identified. Atherosclerotic vascular disease is a systemic process. A patient with claudication may also have a history of coronary artery disease or stroke. Predisposing risk factors for arterial disease can include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, chronic renal insufficiency, and a history of smoking. Venous disease can be associated with obesity, immobility, cancer, trauma, hypercoagulability, and a history of deep venous thrombosis.

Physical Examination

The physical examination links the clinical history and the pathophysiology of the arterial, venous, or lymphatic disease process. The pathology associated with arterial disease can be broadly classified into inflammation-mediated arterial wall changes, arterial wall irregularity or ulceration, stenosis and/or occlusion, and dilatation and aneurysmal degeneration. Veins are normally patent and competent, with functioning valves. Pathologically, intraluminal thrombus can partially or completely obstruct veins. With recanalization of thrombus, veins can become incompetent and lose their valvular function. Valvular incompetence can also develop primarily, independent of previous thrombosis. Finally, if flow through the lymphatic system is disturbed by obstruction, compression, or absence of the lymphatic channels, lymphedema may result.

The physical examination should progress from inspection, to palpation, to auscultation. On inspection, the extremity should be assessed for evidence of skin changes, including atrophy, cyanosis or mottling, pallor, and rubor; hair distribution; and abnormalities in nail growth. The presence and location of edema should be identified and quantified. Tissue loss and ulceration should be noted and fully described, including the location, size, and depth, and the presence of associated cellulitis and inflammation should be documented. Motor function should be documented. On initial palpation, changes in temperature and sensation should be noted and compared with the contralateral extremity. All accessible pulses should be evaluated. At a minimum, pulses should be classified as absent, decreased, or normal. A prominent or widened pulse may suggest aneurysmal degeneration.

Synthesis of the History and Physical Examination

Assessment of a patient with vascular disease is unique, in that it is frequently possible to make a diagnosis and predict the underlying anatomic pathology on the basis of history and physical examination alone. This is important because the anatomy of the disease process can often correlate with the location of symptoms. The history and physical examination should be thought of as a system of checks and balances. Symptoms should correlate with the physical examination and suspected pathology. Such correlation is important because additional evaluation and invasive assessment may not be critical to the initial treatment if the anatomic pathology can be inferred from the history and physical examination.

Arterial Disease—History

Patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) may initially be seen after acute arterial occlusion or with symptoms of chronic arterial insufficiency. Regardless of whether the onset of symptoms is acute or chronic, the chief complaint is generally pain or discomfort. As part of the initial history, it is important to determine the acuteness of onset, the character and intensity of the pain or discomfort, changes in the character and intensity since onset, and its location.

Acute Arterial Occlusion

Acute arterial occlusion may be either embolic or thrombotic in etiology. Classically, acute arterial occlusion is associated with the six “Ps”: pain, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesias, paralysis, and poikilothermy (meaning changing to room temperature, i.e., a cold extremity). Symptoms can occur within minutes to hours after acute arterial occlusion and are associated with a sudden, dramatic decrease in perfusion. Classically, a patient will complain of generalized pain that is severe and not well localized. The patient will notice a change in the color of the extremity, a decrease in sensation, and coolness to touch. Absent motor function is consistent with severe limb-threatening ischemia. An improvement in symptoms over time suggests the development of collateral circulation after the acute arterial occlusion, whereas progression of symptoms suggests lack of collateralization and increasing ischemia.

Acute Arterial Occlusion of the Lower Extremity

As a rule, patients with acute arterial occlusion secondary to an embolic etiology will not have a history of claudication or symptoms suggestive of chronic occlusive arterial disease. Embolic occlusion of the iliac, femoral, or popliteal arteries is frequently associated with a history of atrial fibrillation, and the patient may have had a previous embolic event. In patients who are normally on a regimen of long-term anticoagulation, warfarin (Coumadin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) may have recently been discontinued before a planned intervention, or the patient’s international normalized ratio may have been subtherapeutic. Patients with thrombotic occlusion of the iliac, femoral, or popliteal arteries will frequently have a history of claudication and may have previously undergone arterial bypass or intervention.

Atheroembolism: “Blue Toes Syndrome”

Atheroembolic debris arising from atherosclerotic plaque or ulcerations in the aorta, as well as the iliac, femoral, and popliteal arteries, can result in distal small arterial occlusion. Progressive renal insufficiency can be associated with atheroemboli originating in the thoracic or suprarenal aorta. Patients often have undergone some form of catheter-based procedure involving manipulation of a catheter in the aortic arch or the thoracic and abdominal aorta, or the embolism may be spontaneous.

Distal emboli or thrombotic occlusion can also be due to peripheral arterial aneurysms. Patients will have a painful bluish discoloration of the distal part of the foot or digits, resulting in “blue toe syndrome.” Calf pain can be associated with focal areas of ischemia or tissue necrosis. Symptoms are generally sudden in onset and slow to resolve. The patient often notes that the involved foot or digit feels cool and numb to touch.

Acute Arterial Occlusion of the Upper Extremity

Although less common, acute arterial occlusion may also occur in the upper extremities. The onset and symptoms are similar to those seen in the lower extremities. Emboli associated with atrial fibrillation or recent myocardial infarction are more common but may also originate from aneurysmal disease of the arch or upper extremity arteries. Atheroemboli involving the hand or digits may arise from atherosclerotic irregularity and plaque in the aortic arch or from thrombus associated with a subclavian artery aneurysm. Thrombotic events are infrequent, but may be associated with subclavian artery aneurysms.

Chronic Obstructive Arterial Disease

Patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) most commonly have long-standing symptoms. Chronic occlusive arterial disease encompasses a spectrum of symptoms, beginning with effort discomfort (claudication) and progressing to pain at rest and tissue loss.3 Claudication is derived from the Latin word claudicatio, which means to limp or be lame. Thus, claudication involves the lower extremities and is associated with walking. Effort-induced discomfort with activity involving the upper extremity can be associated with stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian and axillary arteries.4

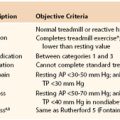

To ease communication between health care professionals who care for patients with PAD, many have adopted the Rutherford classification as the preferred clinical staging system.5 Although it is described in greater extent in other chapters (see Chapters 108 and 109), this clinical staging system ranges from asymptomatic (stage 0), to mild or moderate claudication (stage 3), to severe (stage 6). An example of a patient with stage 0 Rutherford classification would be an elderly patient with a low ankle-brachial index, but no findings of claudication or critical limb ischemia, whereas a patient with Rutherford stage 6 ischemia has severe ulceration and gangrene, as a result of rapidly impending limb-threatening ischemia. The clinical presentation of these entities is described in the following.

Lower Extremity Claudication

Patients with claudication will describe symptoms that are associated with walking. Because the symptoms are secondary to inadequate or decreased circulation, relief occurs promptly after the cessation of activity. Complete relief of symptoms should occur within 5 to 10 minutes, and it should not be necessary for the patient to sit to obtain relief. The exercised-induced symptoms can be described as cramping, aching, fatigue, or numbness; the common denominator is an association with exercise or activity.

Symptoms may have been present for months or years. Anatomically, lower extremity PAD is broadly classified as aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, or tibial. Depending on the location of the arterial obstruction, the patient may have pain in any of the three major muscle groups of the lower extremity: the buttock, thigh, or calf. Symptoms may involve one or more of these muscle groups and may progress from the proximal to the distal part of the extremity or from the calf to the thigh with continued activity. Symptoms will often occur in the muscle group immediately distal to the obstruction. Although obstruction of the superficial femoral artery will cause calf discomfort, aortoiliac disease will result in symptoms involving the buttock or thigh. However, patients with aortoiliac disease can also have associated or isolated discomfort of the calf because the calf is the most distal large muscle group and is used extensively in walking. The triad of intermittent claudication, impotence, and absent femoral pulses is associated with aortoiliac occlusion and is often referred to as Leriche syndrome. In his initial descriptions of the disease process, Leriche et al6 also identified widespread atrophy of the lower extremities and a pale appearance of the extremities and foot.

The severity of symptoms or the extent of disability is usually quantified relative to the distance that a patient can walk or flights of stairs that can be climbed before it is necessary to stop and rest. Usually exercise tolerance deteriorates when walking up a hill or an incline because greater energy expenditure is required than when walking on level ground.

Some patients with PAD confirmed by noninvasive vascular testing may not complain of claudication because comorbid conditions may limit their exercise tolerance. Conversely, other patients may have classic symptoms of claudication but a normal pulse examination. Because initial assessment generally occurs while the patient is at rest on the examining table, it is important to remember that the claudication occurs with walking. In cases when there is a mismatch between the history and physical examination, the physical examination may need to be repeated after exercise.

Conditions Mimicking Arterial Claudication

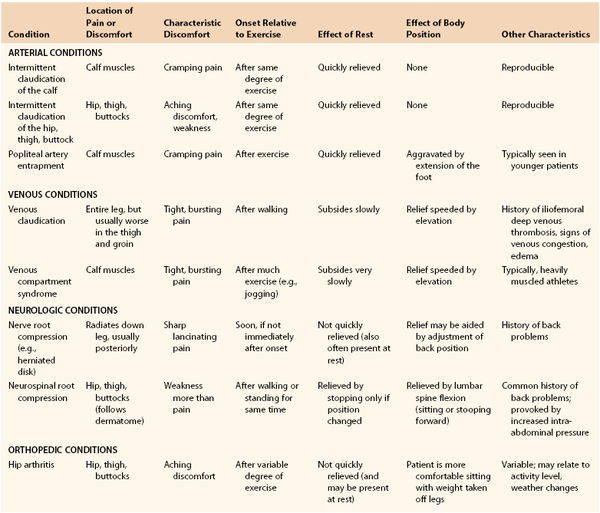

Classically, claudication is associated with arterial stenosis or occlusion, is induced by exercise and relieved by rest, and has an onset that is consistently reproducible. Inconsistencies in the history should suggest the possibility of other causes of the patient’s symptoms. Included in the differential diagnosis of claudication are musculoskeletal, neurologic, and venous pathologies, the most common of which are osteoarthritis, spinal stenosis, and venous outflow obstruction. Symptoms that occur at rest, occur with standing, or are associated with positional changes may suggest osteoarthritis, spinal stenosis, radiculopathy, or venous claudication (Table 14-1).

Patients with atypical claudication of nonarterial etiology will often note pain with exertion, yet the pain does not stop the individual from walking, may not involve the calves or other major muscle groups in the leg, or does not resolve within 10 minutes of rest.7–9 Patients may report the same type of pain in both legs regardless of the associated presence of occlusive disease. Frequently, patients with atypical symptoms often report walking impairment because of joint pain or shortness of breath.7,8

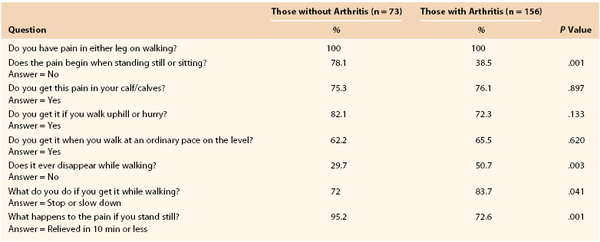

Ultimately, in the evaluation of an individual with leg pain, the examiner has to be cognizant of the patient’s comorbid conditions in an effort to offer the most complete treatment. Newman et al8a compared answers to the Rose Questionnaire in patients with and without arthritis, all of whom had a decreased ankle-brachial index and exertional leg pain. Both groups had pain in the calf or calves on walking at a normal pace, while in a hurry, or when walking uphill. The patients with arthritis, however, had a higher incidence of pain when standing still or sitting, were less likely to continue walking after the onset of pain, and required more than 10 minutes to obtain relief after they had stopped walking (Table 14-2).

Table 14-2

Answers to the Rose Questionnaire by Patients with or without Arthritis, with a Low Ankle-Brachial Index and Exertional Leg Pain, but without Positive Rose Questionnaire Findings for Intermittent Claudication

From Newman AB, et al: For the Cardiovascular Study Research Group: The role of comorbidity in the assessment of intermittent claudication in older adults. J Clin Epidemiol 54:294-300, 2001.

Several previous reports have examined the sensitivity and specificity of the Rose Questionnaire for patients with intermittent claudication. Geoffrey Rose at the London School of Hygiene designed the original questionnaire, which was used to identify patients with intermittent claudication.10 Although the original questionnaire was highly specific (>90%), it was not very sensitive (<70%). Several investigators, including those described previously, have worked to refine the sensitivity of this instrument and others like it. These tools are critical in attempts to discern patients with and without significant claudication from those with other conditions that cause leg pain.

Neurogenic Claudication.

Neurogenic claudication due to spinal stenosis can result from a wide range of conditions causing compression of the spinal cord or its nerve roots in the region of the lumbar spine. It may be associated with aging, arthritis, or inherited deformities of the spine. The symptoms of spinal stenosis are frequently inconsistent in their relationship to exercise or activity. It is not unusual for patients to be limited in their activity one day and be relatively symptom free the next. After the onset of symptoms associated with spinal stenosis, relief does not occur promptly once activity has ceased. Complete symptomatic relief may take 30 to 60 minutes or longer. Commonly, the patient will have to sit down or lean forward. Leaning forward flattens or straightens the lumbar lordosis and often relieves the cord compression.

Venous Insufficiency and/or Venous Claudication.

In an individual with venous claudication, symptoms are associated with a proximal venous obstruction resulting in impaired venous outflow. When an individual begins to exercise or engage in some activity, venous outflow cannot accommodate the increase in arterial flow to the extremity, and high venous pressure develops. The veins become engorged and tense, which causes a bursting sensation or pain that is slowly relieved by rest. The same symptoms can be seen in individuals with chronic venous insufficiency, where persistent venous thrombosis or valvular insufficiency can cause an increase in ambulatory venous pressure that results in chronic lower extremity edema and evidence of postphlebitic skin changes. In these patients, swelling is frequently minimal in the morning but progresses throughout the day with increased activity and dependency of the extremity.

Other Considerations in Young Patients.

Claudication of a vascular etiology most commonly occurs in patients 50 years or older. In younger patients, symptoms of effort discomfort can be associated with popliteal artery obstruction from muscular or tendinous entrapment or mucinous degeneration of the artery. Popliteal artery entrapment11 and popliteal adventitial cystic disease are uncommon conditions usually seen in patients younger than 50 years old (see Chapter 115). Another condition that can be seen in younger patients is chronic compartment syndrome, an overuse syndrome that is often symmetric and bilateral12,13 (see Chapter 163). The most common complaints are muscle cramping and swelling, with focal paresthesias on the plantar or dorsal aspect of the foot. The pain or discomfort is associated with tightness in the calf and is precipitated by exercise. The patient is often an athlete or a runner with large calf muscles. Muscle swelling, increased compartment pressure, and impaired venous outflow constitute a vicious circle. The pain usually starts after considerable exercise and does not quickly subside with rest.

Pain at Rest

Progressive, frequently multilevel atherosclerotic obstructive disease results in ischemic pain at rest. In the absence of acute embolic or thrombotic arterial occlusion, the onset of symptoms is gradual. In most cases, the patient will have a history of claudication. With injury or minor trauma, the patient may have associated nonhealing ulcers. Pain at rest represents a significant decrease in circulation and involves the most distal aspect of the lower extremity that is farthest from the central source of circulation and blood flow. The forefoot and digits are most commonly involved. In the absence of acute arterial occlusion, patients do not have pain in the thigh or calf at rest. The symptoms are classically relieved with dependency, because gravity tends to facilitate circulation. The symptoms are aggravated if the patient lies down and elevates the extremity, which further increases the work of pushing blood against gravity to the foot. Patients will complain that the pain awakens them at night or develops soon after lying down. It is not uncommon for patients to be unable to describe the character of the pain.

It is easiest to quantify the severity of pain at rest relative to the sleep that patients are able to obtain. Early in the course, patients may awaken only occasionally and are able to get back to sleep after sitting up or walking about the room. With time, patients may sleep with their foot constantly hanging over the edge of the bed. Eventually, it is necessary to sleep in a chair with the foot dependent. In the final stages, patients obtain little, if any, sleep.

Conditions Mimicking Pain at Rest

Clinicians should note, and investigate, other etiologies of leg pain, especially when noninvasive tests fail to reveal evidence of PAD. As shown in several examples in the following, inconsistencies in the history can suggest an alternative diagnosis.

Diabetic Neuropathy.

Diabetic patients are prone to a distal arterial occlusive process that frequently involves the tibial and digital arteries and can result in severe ischemia and pain at rest. Diabetic patients can also have associated peripheral neuropathy. Diabetic neuropathy can involve the forefoot and digits and is often described as a burning pain, hyperesthesia, or a “pins and needles” sensation. A careful history should permit differentiation between ischemic pain at rest and neuropathy, because neuropathic pain is constant and unrelieved by dependency.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome.

Complex regional pain syndrome (or reflex sympathetic dystrophy or causalgia) is described in detail in Chapter 85. Often the pain originates after soft issue or nerve injury. Pain is the most common and prominent feature. The pain is frequently burning and can be worse in the distal aspects of the extremity. The pain is not known to be associated with any exacerbating events and can occur at any time.14 Associated clinical features include signs of autonomic nerve dysfunction, resulting in edema and changes in skin color in the early stages. Later, the patient may have pallor or cyanosis, and a cool, moist sensation to touch. Generalized wasting involving the muscle, skin, and subcutaneous tissue may develop. There is also marked weakness and a decreased range of motion in the joints.

Upper Extremity Effort Discomfort

Effort discomfort involving the upper extremity can be associated with stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian or axillary arteries. Like claudication, symptoms are induced by exercise and relieved by rest. A careful history should allow the examiner to make a distinction between symptoms related to arterial disease and those associated with thoracic outlet syndrome. In neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, the nerve roots that form the brachial plexus and its trunks are compressed within the scalene triangle. Patients will complain of weakness, fatigue, or heaviness with activities involving the affected extremity. The pain or symptoms that they experience can be positional and are exacerbated by abduction or elevation of the arm. Patients will complain of neck, shoulder, and arm discomfort when working with the arms elevated above the head or with the hands in the 10- and 2-o’clock positions while driving a car or reading a newspaper. Extended activity can result in paresthesias.

Arterial Disease—Physical Examination

Regardless of the suspected vascular pathology, physical examination of an individual with suspected arterial disease should be complete because of the systemic nature of the atherosclerotic process underlying arterial disease.

Inspection

The examination begins with observation or inspection of the extremities. Significant PAD can be associated with atrophy of the calf muscles; loss of hair growth over the lower part of the leg and foot is also a common sign of arterial insufficiency, as is thickening of the nails. With more advanced changes, atrophy of the skin is seen, there is a decrease in subcutaneous tissue, and the skin assumes a fragile, shiny appearance. With severe ischemia, dependent rubor is observed, and the distal part of the leg, the foot, and the digits may appear reddish. On elevating the lower extremity, the rubrous appearance is replaced with pallor. In advanced stages of critical limb ischemia, the foot may appear edematous and the skin shiny and tense because the patient frequently hangs the foot dependently in an attempt to relieve the ischemic rest pain by relying on gravity to augment blood flow.

Ischemic Ulcers

With increasing ischemia, the formation of ischemic ulcers can be observed. These ulcers are small and circinate, with pale, grayish granulation tissue in the base. They are noted specifically on the toes, heels, or fingertips, and if found more proximally, they are usually secondary to trauma. When examining the foot and digits for ischemic ulcers, care should be taken to examine between the toes because skin breakdown and small fissures can frequently begin in these intertriginous areas. Ischemic ulcers are usually painful and can progress to tissue necrosis and frank gangrene. Gangrene can consist of dry eschar, or be “wet” due to purulent or serous drainage at the margins of the eshar. Table 14-3 provides a model that can be used to describe and document ischemic ulcers and wounds in uniform fashion.

Table 14-3

Documentation of Wound Characteristics

| Characteristic | Observations to Be Documented |

| Wound size | Length, width, depth, area, volume |

| Undermining | Presence, location, measurement |

| Appearance | Granulation tissue, sloughing, necrotic eschar, friability |

| Exudate | Amount, color, type (serous, serosanguineous, sanguineous, purulent), odor |

| Wound edge | Presence of maceration, advancing epithelium, erythema, even, rolled, ragged |

From Lawrence PF, et al: The wound care center and limb salvage. In Moore WS, editor: Vascular and endovascular surgery. A comprehensive review, ed 7. Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders Elsevier, pp 876-889.

Livedo Reticularis

Close examination of the skin may reveal abnormalities such as livedo reticularis, which is a discoloration of the skin consisting of macular, violaceous, connecting rings that form a netlike or lacelike pattern. Decreased flow leading to hypoxia and collateral formation are thought to cause the cutaneous findings. Livedo reticularis can be due to PAD and be found in areas of ischemia. More often, it is secondary to vasculitis, calciphylaxis, atheroemboli, hyperviscosity syndromes, endocrine abnormalities, infection, or any combination of these causes. In these latter forms, the lesions are usually more diffuse. In situations in which the microcirculation is affected, splinter hemorrhages, focal areas of cyanosis, or punctate violaceous lesions can be indicative of microemboli. These lesions can often be multiple, but they can also occur in single form. The lesions are generally small in overall diameter and are frequently found to be painful.15,16

Acrocyanosis

Although a precise definition of acrocyanosis remains elusive, it is a generalized term used to describe painless, symmetric, cyanotic discoloration of the hands, feet, and occasionally face and central portions of the body such as the tips of ears or nose.17 Episodes of acrocyanosis are often triggered by cold exposure.18,19 Distinction from Raynaud-like phenomena are difficult to discern. The diagnosis often relies on clinical interpretation based on the duration and persistence of the color changes, which usually persist longer than Raynaud phenomenon. Physical examination may reveal “Crocq sign,” which is described as slow resolution of the discoloration of the skin after blanching in a radial pattern. Although common in patients with acrocyanosis, this physical examination finding is not specific. Many of these symptoms are exacerbated in cold environments, and often improve with cessation of cold triggers. Given that the episodes of discoloration associated with acrocyanosis are painless, cause no tissue loss, and are self-limited, little treatment is required for acrocyanosis.

Pulse Examination

Palpation of pulses should be performed in a relatively consistent manner and should be complete. The examiner should avoid using the thumb for palpation because the transmitted pulse in the pulp of the thumb can be distracting. Although pulses are frequently graded on a scale from 0 to 4, observer variability makes the reliability of this scale suspect. It is probably more practical to simply document that a pulse is absent, decreased, or normal. Comparing a pulse with that in the contralateral extremity can demonstrate important relative differences. In addition to pulses in the neck and the upper and lower extremities, the abdominal aortic pulse should also be assessed.

The carotid pulse can best be palpated in the midneck region, anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Superficial temporal artery pulses should also be documented, particularly when evaluating temporal arteritis. The temporal artery is preauricular and can be followed onto the medial aspect of the forehead. The subclavian pulse is usually found in the supraclavicular fossa, and the axillary pulse is found lateral to the clavicle along the course of the deltopectoral groove or in the axilla. Upper extremity pulses are examined in the antecubital fossa and at the wrist. Both the brachial and radial pulses can generally be felt with superficial palpation. The ulnar pulse, in contrast, does require firmer palpation because this artery follows a deeper course than the radial or brachial arteries. In the lower extremity, the common femoral, popliteal, dorsal pedal, and posterior tibial artery pulses are examined. The common femoral artery pulse can usually be found in the medial aspect of the groin, just below the inguinal ligament, and can be felt with light palpation in a thin person; however, deeper palpation is necessary in an obese individual. Popliteal artery pulses are more difficult to palpate because they are generally located lateral to the popliteal fossa. The patient’s knee should be partially flexed and relaxed to allow the examiner to palpate the pulse; firm pressure is required. The posterior tibial artery pulse is typically found in the hollow posterior to the medial malleolus, and usually gentle pressure allows adequate palpation. Increased pressure, particularly in patients with poor arterial perfusion, can obscure the pulse. The dorsal pedal pulse is generally found on the dorsum of the foot between the first and second metatarsal bones. In 10% of patients, the dorsal pedal pulse is absent congenitally. In patients with suspected popliteal artery entrapment, tibial pulses should also be evaluated during active plantar flexion of the foot or during passive dorsiflexion.

Arterial Aneurysms

During the course of the pulse examination, the size of the artery should be assessed. Typically, an aneurysm is first suspected by a prominence of the palpated pulse. If a prominent pulse is appreciated, the artery should be further evaluated to determine whether aneurysmal dilatation is present, and if it is, the size of the aneurysm should be estimated and noted. Peripheral aneurysms are most commonly found in the popliteal, common femoral, and subclavian arteries. The abdominal aorta can be palpated in thin individuals by having them relax their abdominal musculature and then palpating deeply. In patients in whom it is difficult to examine the aorta, it is sometimes useful to ask them to take a deep breath and exhale. Deep palpation can usually be achieved as the patient slowly exhales through the mouth. The right and left lateral walls of the aorta should be localized to estimate aortic diameter.

Auscultation

After palpation, the arteries should be auscultated. Although typically nothing is heard on auscultation, the presence of a bruit, which is indicative of turbulent blood flow, is a marker of underlying pathology. Generally speaking, the pitch and duration of a systolic bruit are correlated with increasing severity of arterial narrowing, but it is difficult to quantify the degree of stenosis. Bruits extending into diastole may suggest the presence of an arteriovenous fistula. Although uncommon in the past, arteriovenous fistulae are being seen with increasing frequency because of the rising number of arterial catheterizations.

Palmar Circulation

In patients with upper extremity arterial disease, it may be of value to assess the patency of the palmar arch. Typically, circulation to the hand is supplied by both the radial and ulnar arteries. These two arteries merge to form the palmar arch. In approximately 10% of the population, the arch is congenitally incomplete. The Allen test can demonstrate the presence of an incomplete arch or occlusion of the arch. In this test, pressure is applied at the wrist to occlude the radial and ulnar arteries. The patient is asked to open and close the hand, making a fist. After several repetitions, the palmar aspect of the hand blanches and becomes pale. With release of pressure over the radial or ulnar artery, normal skin color should return within seconds. The other artery is then tested in a similar manner. Persistent blanching of the palm or slowly resolving pallor suggests either an incomplete arch or occlusion of the radial or ulnar artery. The test is also frequently used before dialysis access surgery or placement of a radial artery catheter.

Venous and Lymphatic Disease—History

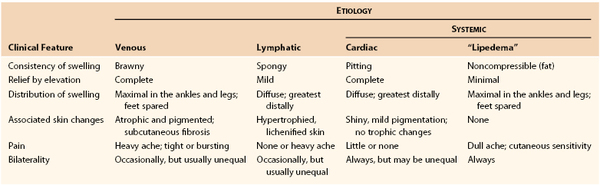

Vascular surgeons are frequently asked to evaluate a swollen or edematous extremity. The onset may have been acute, or the symptoms may be more chronic and long-standing. One or both extremities may be involved. The swelling may have been stable over time or have shown evidence of progression. Commonly, the patient obtains relief with elevation. The clinical history is particularly important in the evaluation of a patient with swelling to assist in excluding potential causes from the differential diagnosis. The etiology may be venous (related to the superficial and deep veins of the lower extremity), or nonvenous (generally related to disorders of the lymphatic system or other systemic illnesses) (Table 14-4).

Venous Disease

Patients with venous disease may initially be seen after acute venous problems, such as venous thrombosis, or with symptoms associated with chronic venous occlusion or valvular incompetence with venous reflux. The approach and focus for each of these problems differs, and is outlined in the following sections.

Symptoms in Acute Venous Disease

In patients with acute venous thrombosis, either the superficial or the deep veins can be involved. Superficial venous thrombosis is associated with a localized inflammatory process around the involved vein. The patient complains of tenderness along the course of the vein, which is associated with a painful, erythematous area of inflammation and induration. In the lower extremity, this is typically along the medial aspect of the leg and involves the great saphenous vein and its branches, but superficial thrombophlebitis may also be associated with varicosities in disparate distributions over the surface of the lower extremity. Thrombophlebitis may also involve the cephalic and basilic veins in the upper extremity and is frequently associated with indwelling venous catheters. A recent history of deep venous thrombosis may have resulted in the acute onset of swelling. Symptoms are generally unilateral; thrombosis of the iliac and femoral veins can result in swelling of the entire extremity, whereas thrombosis of the distal femoral and popliteal veins is associated with swelling of the calf. Patients frequently report a recent history of surgery, trauma, travel, or prolonged immobilization. They may have a diagnosis of cancer or report a previous episode of deep venous thrombosis. Over time, the thrombotic obstruction can resolve as the veins recanalize, and the patient is left with valvular incompetence, venous insufficiency, and chronic swelling or edema.

Symptoms in Chronic Venous Disease

In patients with chronic venous insufficiency, symptoms are usually described as pain or discomfort and swelling of the extremity. Long-standing venous insufficiency can result in ambulatory venous hypertension and edema. Long-standing symptoms of venous hypertension and swelling can ultimately result in the development of venous stasis ulcers. As with arterial disease, it is important to determine the acuteness with which the symptoms developed, the character and intensity of the symptoms, any changes in the character and intensity since onset, and the location of any pain and/or discomfort or swelling. In obtaining the history, it is important to remember that chronic symptoms can develop 5 to 10 years after an episode of deep venous thrombosis and that the patient may not recall the initial episode of deep venous thrombosis. Consequently, the patient should also be questioned about a history of predisposing risk factors, such as long-bone fracture, pelvic surgery, or prolonged immobilization.

Upper Extremity Venous Thrombosis

Although many consultations seen by vascular physicians are related to swelling in the lower extremity, vascular specialists often see patients with swollen upper extremities as well. Deep venous thrombosis may also involve the subclavian and axillary veins in the upper extremities. Its onset is typically acute and associated with swelling of the entire arm. There has always been a strong relationship between venous thrombosis and compression of the subclavian vein at the thoracic outlet, and patients will frequently note an association with upper body exercise and activity. More recently, subclavian and axillary vein thrombosis has increasingly been associated with subclavian vein catheters placed for central access.

Lymphatic and Systemic Disease

Swelling of Lymphatic Origin

Although many patients with swollen limbs have swelling that is secondary to venous insufficiency, dysfunction in the lymphatic system also presents a potential cause of lower extremity swelling. The lymphatic system functions to return protein lost from plasma back to the circulation. Obstruction of lymphatics results in the accumulation of protein and fluid in the interstitial tissues. The resulting swelling is termed lymphedema. Lymphedema may be classified as primary or secondary in etiology, as familial or sporadic, and relative to the age at onset.20,21 Primary lymphedema is associated with aplasia, hypoplasia, or hyperplasia, and incompetence of the lymphatic system. The clinical manifestation is usually painless leg swelling or mild discomfort. The edema is typically unilateral, and elevation of the extremity does not generally result in resolution of the edema. The swelling usually begins distally and involves the area about the ankle. There is also involvement of the dorsum of the foot. Initially, the edema is pitting, but with time, the skin and subcutaneous tissue become more fibrotic. Not infrequently, patients may have inflammation secondary to lymphangitis. The patient commonly has swelling and heaviness of the affected limb.

Swelling of Systemic Origin

Systemic causes of lower extremity swelling generally result in bilateral lower extremity edema. The most common cause of bilateral lower extremity swelling is cardiac dysfunction and congestive heart failure. Renal failure and liver failure are other common systemic causes. Additional causes may include endocrine disorders or a medication side effect associated with calcium channel blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, or oral hypoglycemic agents. Localized trauma or injury is usually associated with unilateral swelling. The common denominator among systemic causes of lower extremity swelling is fluid overload or retention. Frequently, progressive swelling of the legs is the first manifestation of heart failure. It may also be associated with dyspnea and orthopnea. Not uncommonly, women can have chronically “swollen” legs with none of the foregoing characteristics. These patients, as well as their female relatives, have a maldistribution of fat characterized by excessive peripheral deposition in the arms and legs. For unknown reasons, these women are prone to superimposed orthostatic edema and complain of a dull ache and sensitivity involving the overlying skin. This swelling, sometimes referred to as lipedema, never completely subsides with elevation or diuretics. Furthermore, it is symmetric, with noticeable sparing of the feet.22,23

Venous Disease—Physical Examination

As in patients with a history suggestive of arterial occlusive disease, physical examination of patients with suspected venous disease should be complete rather than focused. The examiner should begin with inspection or observation of the extremities. The presence of any swelling or edema should be noted and described. Unilateral or bilateral involvement should be noted, as well as the extent of involvement (i.e., is the entire extremity swollen or just the calf and foot?). Swelling associated with acute deep venous thrombosis or chronic venous insufficiency is frequently unilateral. The entire extremity may be swollen in patients with iliofemoral venous thrombosis, whereas femoropopliteal venous obstruction often results in swelling of the distal end of the extremity or calf.

As with the approach taken for this history of patients with leg swelling, the approaches taken for physical examination are divided into venous (acute and chronic) and nonvenous etiologies, focusing primarily on lymphedema.

Acute Venous Disease

Superficial Thrombophlebitis

Patients with superficial thrombophlebitis will have a localized area of erythema and induration that can readily be identified on initial inspection of the extremity. Most commonly, the inflammation will parallel the course of the great or small saphenous vein, although clusters of varicosities anywhere on the extremity can become acutely thrombosed and demonstrate inflammatory changes. There may or may not be associated swelling of the extremity. On palpation, the involved vein can be felt as a subcutaneous cord. The area is exquisitely tender to touch.

Deep Venous Thrombosis

Patients with acute deep venous thrombosis typically have unilateral leg swelling. The extremity may appear cyanotic secondary to venous congestion. Erythema can also be observed, and increased warmth may be appreciated on palpation. Variants of deep venous thrombosis have been described. Phlegmasia alba dolens, or “milk leg of pregnancy,” describes a pale, white extremity that has been frequently seen in the postpartum period. Homans24 attributed the findings to an underlying iliofemoral venous thrombosis. Collateral veins were noted over the upper part of the thigh and abdomen. The swelling was frequently associated with fever and pain in the calf, popliteal fossa, or groin. The absence of bluish discoloration was attributed to the rapid development of collateral venous flow. Phlegmasia cerulean dolens is associated with extensive proximal venous obstruction and minimal collateralization. The leg is massively swollen and cyanotic. Left untreated, the condition can lead to venous gangrene.

Homans sign describes the association between calf vein thrombus and calf pain with passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Other clinical findings that have been associated with acute deep venous thrombosis include Bancroft sign, or tenderness on the anteroposterior but not lateral compression of the calf, and Lowenberg sign, or calf pain associated with inflation of a blood pressure cuff about the calf. Unfortunately, none of these “signs” are diagnostic of deep venous thrombosis. Hospitalized patients with deep venous thrombus can be asymptomatic, and approximately half of nonhospitalized patients with symptoms suggesting deep venous thrombosis will not have venous pathology. The differential diagnosis includes trauma, cellulitis, muscle strain or tear, Baker cyst, hematoma, or dermatitis. Although the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis can be suspected on the basis of pain, swelling, and associated risk factors, noninvasive imaging remains a necessary adjunct to confirm the suspected diagnosis.

Chronic Venous Disease

Chronic Venous Insufficiency and/or Venous Stasis

Long-standing venous insufficiency in the deep or superficial veins (or in both) can result in chronic venous stasis changes. Mild swelling and pitting edema are replaced by a brawny induration. Hemosiderin deposits result in a brownish pigmentation and discoloration in a typical “gaiter” distribution about the distal part of the leg and ankle. Ultimately, large, irregular, generally painless ulcerations can be observed. Table 14-4 can be used to develop a uniform and consistent template for describing the ulcers. The CEAP classification has also been used to standardize the description of chronic venous disease.25 The classification incorporates clinical findings (C), etiology (E), anatomy (A), and pathophysiology (P) (see Table 55-1).

Varicose Veins

Patients with varicose veins generally do not complain of a discrete location of severe pain. Rather, the discomfort is described as burning or throbbing, and is localized to the general area of the varicosities. Swelling of the calf and foot can often be associated with varicosities. Patients also observe that symptoms increase during the course of the day, particularly if they are ambulatory and active. Patients with varicose veins should be examined in the standing position.

The location of all varicosities should be noted. Varicosities along the medial aspect of the leg are generally related to the great saphenous vein or its perforating branches; varicosities over the posterior calf region are in the distribution of the small saphenous vein, which begins on the lateral aspect of the foot and ascends along the posterior midline of the calf.

Venous reflux in the great saphenous vein may be associated with incompetence at the saphenofemoral junction or may be related to incompetent deep and perforating veins. The great saphenous vein can communicate with the Dodd, Boyd, Cockett, Sherman, and the Hunterian perforating veins. Hunterian perforator incompetence can be associated with varicosities in the middle third of the thigh. The Dodd perforator is located in the medial and distal third of the thigh, the Boyd perforators are along the medial aspect of the knee, and the Cockett and Sherman perforators are located at the ankle.

In patients with varicosities, the examiner can usually distinguish superficial from deep venous incompetence with the Brodie-Trendelenburg test. In this test, the patient is placed supine, the leg is elevated, and a tourniquet is placed around the proximal end or midportion of the thigh after all the superficial varicosities have been decompressed. For patients with isolated distal varicosities, the tourniquet can be placed above or below the knee, but proximal to the varicosities. The examiner then has the patient stand. In a patient without deep venous thrombosis, the veins below the tourniquet should fill slowly. If the veins refill promptly, in less than 30 seconds, the test is suggestive of incompetent deep and perforating veins. If the veins do not refill or refill slowly, the tourniquet should be removed. If after tourniquet removal, the varicosities fill rapidly, in less than 35 seconds, superficial venous incompetence is suspected.

Lymphatic Disease

Lymphedema is also frequently unilateral, beginning at the ankle and ascending proximally. The dorsum of the foot and digits may also be involved. Systemic causes of swelling usually result in bilateral lower extremity involvement.26–28 If indicated, the extent of lymphedema may be quantified by measuring the circumference of the thigh or calf and comparing the measurement with that of the uninvolved contralateral extremity.

Other causes of lymphedema often relate to local lymph node dissection, such as an inguinal node dissection for extremity melanoma.29,30 In this setting, physical examination will reveal stiffened, indurated skin as a nearly universal finding in these patients. This can be difficult to manage even with multimodality approaches such as physical therapy, ultrasound manipulation, and massage. Attempts to use different, less invasive surgical techniques to limit the occurrence of lymphedema have not yet been met with great success, but continue to be a source of current investigation.

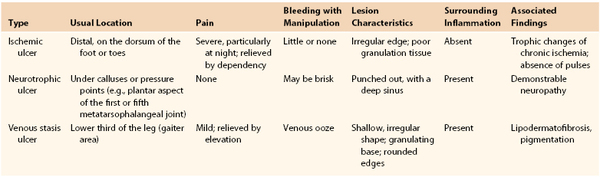

The Ulcerated Leg

Chronic ulcers can be associated with arterial ischemia, venous stasis, and neuropathy (Table 14-5). The history and physical examination are critical because the causes are not mutually exclusive. A history of arterial insufficiency, including claudication and pain at rest, should be sought. Ischemic ulcers and tissue loss represent the far end of the spectrum of arterial disease. Diabetics can have arterial disease and peripheral neuropathy. Neuropathy can predispose diabetic patients to neurotrophic ulcers over the weight-bearing prominences of the plantar surface of the foot. Venous stasis disease can result in characteristic ulcerations, but associated arterial disease can affect healing and influence treatment. The history should be accompanied by a complete physical examination, beginning with observation and inspection of the extremity. All areas of ulceration and tissue loss should be fully characterized with respect to location and size (see Table 14-5); the status of all pulses should be documented.

Ischemic Ulcers

Ischemic ulcers are usually painful, and there is likely to be typical ischemic pain at rest in the distal part of the forefoot that occurs nocturnally and is relieved by dependency. At first, these ulcers may have irregular edges, but when chronic, they are more likely to be “punched out.” They are commonly located distally over the dorsum of the foot or toes but may occasionally be pretibial. The ulcer base usually consists of poorly developed, grayish granulation tissue. The surrounding skin may be pale or mottled, and the previously described signs of chronic ischemia are invariably present. Notably, the usual signs of inflammation expected surrounding such a skin lesion are absent because it lacks adequate circulation to provide the necessary inflammatory response for healing that underlay ischemic ulcers. For the same reason, probing or débriding the ulcer causes little bleeding.

Neurotrophic Ulcers

Neurotrophic ulcers are completely painless but bleed with manipulation. They are deep and indolent, and are often surrounded not only by acute but also by chronic inflammatory reaction and callus. Their location is typically over pressure points or calluses (e.g., the plantar surface of the first or fifth metatarsophalangeal joint, the base of the distal phalanx of the great toe, the dorsum of the interphalangeal joints of toes with flexion contractures, or the callused posterior rim of the heel pad). The patient generally has long-standing diabetes with a neuropathy characterized by patchy hypoesthesia and diminution of positional sense, two-point discrimination, and vibratory perception.

Stasis Ulceration

The so-called venous stasis ulcer, actually secondary to ambulatory venous hypertension, is located within the gaiter area, most commonly near the medial malleolus. It is usually larger than the other types of ulcers and irregular in outline, but it is also shallower and has a moist granulating base. The ulcer is almost invariably surrounded by a zone containing some of the hallmarks of chronic venous insufficiency—pigmentation and inflammation (“stasis dermatitis”), lipodermatofibrosis, and cutaneous atrophy, as previously described.

Other Types of Ulcers

More than 95% of all chronic leg or foot ulcers fit into one of the three previously described recognizable types. The remainder are difficult to distinguish, except that they are not typical of the other three types. Leg ulcers may also be produced by vasculitis and hypertension. Vasculitis frequently produces multiple punched-out ulcers and an inflamed indurated base that on biopsy suggests fat necrosis or chronic panniculitis. Hypertensive ulcers represent focal infarcts and are very painful. They may be located around the malleoli, particularly laterally. Long-standing ulcers that are refractory to treatment may represent underlying osteomyelitis or a secondary malignant lesion.

Finally, most patients with ulcers identify trauma as an initiating cause. In diabetics, ulcers may also be related to poorly fitting shoes that result in persistent irritation or trauma or uneven weight distribution on the plantar surface of the foot. Although trauma of some form may be the initial cause, chronicity of the ulcer may be related to self-inflicted trauma, continuing irritation or uneven weight distribution associated with a poorly fitted shoe, underlying osteomyelitis, or arterial insufficiency.

Selected Key References

Gibbs MB, English JC, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1009–1019.

A comprehensive review of the physical finding of livedo reticularis, including the definition, causes, and contemporary evaluation and treatment algorithms.

Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Murphy WRC, Olin JW, Puschett JB, Rosenfield KA, Sacks D, Stanley JC, Taylor LM, White CJ, White J, White RA. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation. 2005;113:e463–e654.

Comprehensive review of the epidemiology, diagnostic methods, and current treatment recommendations for patients with peripheral vascular disease.

Kurklinsky AK, Miller VM, Rooke TW. Acrocyanosis: the flying dutchman. Vasc Med. 2011;16:288–301.

A well-written summary of the definitions, differential diagnoses, and presenting signs and symptoms of patients with acrocyanosis.

Turnipseed WD. Popliteal entrapment syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:910–915.

Review of the anatomy, epidemiology, clinical findings, diagnostic methods, and treatment of popliteal artery entrapment.

Wang JC, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Golomb BA, Fronek A. Exertional leg pain in patients with and without peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2005;112:3501–3508.

Study reviewing the multiple clinical findings in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Three cohort studies combined for cross-sectional analysis reveal that exertional leg pain alone is often not sensitive or specific enough for routine diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease.

The reference list can be found on the companion Expert Consult website at www.expertconsult.com.

References

1. Katzel LI, et al. Comorbidities and the entry of patients with peripheral arterial disease into an exercise rehabilitation program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20:165–171.

2. Holloway GA Jr. Arterial ulcers: assessment and diagnosis. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1996;42:46–48.

3. Hirsch AT, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): A collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease): Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; Transatlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. [American Association for Vascular S, Society for Vascular S, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and I, Society for Vascular Medicine and B, Society of Interventional R, Disease AATFoPGWCtDGftMoPWPA, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary R, National Heart LaBI, Society for Vascular N, TransAtlantic Inter-Society C, Vascular Disease F] Circulation. 2006;113:e463–e654.

4. Wang JC, et al. Exertional leg pain in patients with and without peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2005;112:3501–3508.

5. Rutherford RB, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517–538.

6. Leriche R, et al. The syndrome of thrombotic obliteration of the aortic bifurcation. Ann Surg. 1948;127:193–206.

7. Hirsch AT, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–1324.

8. McDermott MM, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286:1599–1606.

8a. Newman AB, et al. The role of comorbidity in the assessment of intermittent claudication in older adults. [for the Cardiovascular Study Research Group] J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:294–300.

9. McDermott MM, et al. Prevalence and significance of unrecognized lower extremity peripheral arterial disease in general medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:384–390.

10. Rose GA. The diagnosis of ischaemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;27:645–658.

11. Turnipseed WD. Popliteal entrapment syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:910–915.

12. Turnipseed WD. Diagnosis and management of chronic compartment syndrome. Surgery. 2002;132:613–617.

13. Turnipseed W, et al. Chronic compartment syndrome. An unusual cause for claudication. Ann Surg. 1989;210:557–562.

14. Vignes S. Physical therapy in limb lymphedema. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:185–187.

15. Herrero C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of livedo reticularis on the legs. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:598–607.

16. Gibbs MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1009–1019.

17. Kurklinsky AK, et al. Acrocyanosis: the flying dutchman. Vasc Med. 2011;16:288–301.

18. Glazer E, et al. Asymptomatic lower extremity acrocyanosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Vascular. 2011;19:105–110.

19. Heidrich H. Functional vascular diseases: Raynaud’s syndrome, acrocyanosis and erythromelalgia. Vasa. 2010;39:33–41.

20. Cemal Y, et al. Preventative measures for lymphedema: separating fact from fiction. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:543–551.

21. Wagner S. Lymphedema and lipedema—an overview of conservative treatment. Vasa. 2011;40:271–279.

22. Karakousis CP. Surgical procedures and lymphedema of the upper and lower extremity. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:87–91.

23. Saijo M, et al. Lymphedema. A clinical review and follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:513–521.

24. Homans J. Thrombophlebitis of the lower extremities. Ann Surg. 1928;87:641–651.

25. Porter JM, et al. Reporting standards in venous disease: an update. International Consensus Committee on chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:635–645.

26. Ryan TJ. Risk factors for the swollen ankle and their management at low cost: not forgetting lymphedema. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2002;1:202–208.

27. Pappas CJ, et al. Long-term results of compression treatment for lymphedema. J Vasc Surg. 1992;16:555–562.

28. Buchbinder MR, et al. Lymphedema praecox and yellow nail syndrome: a literature review and case report. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1978;68:592–594.

29. Wanchai A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine and lymphedema. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:41–49.

30. Chang CJ, et al. Lymphedema interventions: exercise, surgery, and compression devices. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:28–40.