1 Patient Assessment and Care Management

Note 1: This book is written to cover every item listed as testable on the Entry Level Examination (ELE), Written Registry Examination (WRE), and Clinical Simulation Examination (CSE).

The listed code for each item is taken from the National Board for Respiratory Care’s (NBRC) Summary Content Outline for CRT (Certified Respiratory Therapist) and Written RRT (Registered Respiratory Therapist) Examinations (http://evolve.elsevier.com/Sills/resptherapist/). For example, if an item is testable on both the ELE and WRE, it is shown simply as (Code: …). If an item is testable only on the ELE, it is shown as (ELE code: …). If an item is testable only on the WRE, it is shown as (WRE code: …).

Note 3: The Entry Level Examination has shown an average of 2 questions that directly cover a cardiopulmonary pathology issue; the Written Registry Examination has shown an average of 1 question. It is beyond the scope of this book to cover all the cardiopulmonary diseases and conditions that befall patients for whom respiratory therapists may provide care. It is recommended that asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; emphysema or chronic bronchitis or both), pneumonia, pneumothorax, flail chest, congestive heart failure with pulmonary edema, myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, head (brain) injury with increased intracranial pressure, pediatric croup and epiglottitis, infant respiratory distress syndrome, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and smoke inhalation with carbon monoxide poisoning be studied. Some limited discussion of these topics is covered in this book. The Written Registry Examination frequently ask questions about the respiratory therapy procedures that patients with these types of problems are receiving. In addition, the 11 Clinical Simulation Examination scenarios are built around the care of patients with these types of diseases and conditions. See Box 1 in the Introduction.

MODULE A

1. Review the patient’s history: present illness, admission notes, progress notes, diagnoses, respiratory care orders, medication history, do not resuscitate (DNR) status, and previous patient education (Code: IA1) [Difficulty: ELE is R; WRE: Ap]

a. Patient history

Review the complete initial patient history and note the following:

d. Diagnoses

After the medical history, physical exam, and laboratory tests are completed, the patient will be placed into one of the following four diagnostic categories. Refer to Table 1-1 for examples of each category:

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Crisis/acute onset of illness | Trauma, heart attack, allergic reaction, aspiration of a foreign body, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, and some pneumonias |

| Intermittent but repeated Illness | Asthma, chronic bronchitis, congestive heart failure, angina pectoris, myasthenia gravis, and some pneumonias |

| Progressive worsening | Congestive heart failure, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and upper respiratory tract infection leading to bronchitis or pneumonia |

| Mixed patterns/multiple problems | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis complicated by multiple problems, mucous plugging or infection; mixes of congestive heart failure and chronic lung disease; mixes of neuromuscular and lung disease; mixes of renal failure and congestive heart failure with chronic lung disease |

2. Review the results of the patient’s physical examination and vital signs (Code: IA2) [Difficulty: ELE: R; WRE: Ap]

c. Respiratory rate

The respiratory rate (f for frequency) is the number of breaths the patient takes in 1 minute. The number is counted by looking at or feeling the chest or abdominal movements, or both. The normal rate varies with age (Table 1-2). It is assumed that the patient is resting but awake and has a normal temperature and metabolic rate. A respiratory rate above or below normal is cause for alarm.

| Age (Years) | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 31 ± 8 | 30 ± 6 |

| 1-2 | 26 ± 4 | 27 ± 4 |

| 2-4 | 25 ± 4 | 25 ± 3 |

| 5-7 | 22 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 |

| 8-11 | 19 ± 2 | 19 ± 2 |

| 12-14 | 19 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 |

| 15-16 | 17 ± 3 | 18 ± 3 |

| 17-18 | 16 ± 3 | 17 ± 3 |

| Older | 16 ± 3 | 17 ± 3 |

Modified from Eubanks DH, Bone RC: Comprehensive respiratory care, ed 2, St Louis, 1990, Mosby.

d. Blood pressure

Hypertension in the adult is a systolic BP of 140 mm Hg or greater or a diastolic BP of 90 mm Hg or greater, or both. Carefully measure the BP of any patient with a history of hypertension, bounding pulse, or symptoms of a stroke (mental confusion, headache, and sudden weakness or partial paralysis). Fear, anxiety, and pain also cause the patient’s BP to increase temporarily.

e. Heart/pulse rate

The heart/pulse rate (HR) is the number of heartbeats per minute. It can be counted by listening to the heart tones with a stethoscope or by feeling any of the common sites where an artery is easy to locate. Table 1-3 shows the normal pulse rates based on age. It is assumed that the patient is alert but resting when the pulse is counted. Carefully measure the heart/pulse rate in any patient with cardiopulmonary disease or any of the aforementioned conditions for hypotension or hypertension.

| Age | Beats/min |

|---|---|

| Birth | 70–170 |

| Neonate | 120–140 |

| 1 year | 80–140 |

| 2 years | 80–130 |

| 3 years | 80–120 |

| 4 years | 70–115 |

| Adult | 60–100 |

From Eubanks DH, Bone RC: Comprehensive respiratory care, ed 2, St Louis, 1990, Mosby.

3. Serum electrolytes and other blood chemistries

a. Review the results of the patient’s serum electrolyte levels and other blood chemistries (Code: IA3) [Difficulty: ELE: R; WRE: Ap]

b. Recommend blood tests, such as the potassium level, to obtain additional data (WRE code: IC1) [Difficulty: WRE: R, Ap, An]

The serum (blood) electrolytes are measured in most patients when they are admitted to the hospital and as needed thereafter. This is to determine whether the values are within the normal ranges listed in Table 1-4. Any abnormality should be promptly corrected so that the patient’s nervous system, muscle function, and cellular processes can be optimized. Diet and a number of medications can affect the various electrolytes. Most abnormalities can be corrected by dietary adjustments or, if necessary, by oral or intravenous supplementation.

| NORMAL ELECTROLYTE VALUES* | |

| Chloride (Cl−) | 95–106 mEq/L |

| Potassium (K+) | 3.5–5.5 mEq/L |

| Sodium (Na+) | 135–145 mEq/L |

| Calcium (Ca++) | 4.5–5.5 mEq/L |

| Bicarbonate (HCO3−) | 22–25 mEq/L |

| NORMAL GLUCOSE VALUES* | |

| Serum or plasma | 70–110 mg/100 mL (dL) |

| Whole blood | 60–100 mg/100 mL (dL) |

* These values may vary somewhat among references.

1. Potassium (K+)

Potassium is the most important electrolyte to monitor because of its effect on general nerve function and cardiac function. Hyperkalemia is a high blood level of potas-sium. It causes the following electrocardiographic (ECG) changes: high, peaked T waves and depressed S-T segments; widening QRS complex; and bradycardia. Hypokalemia is a low blood level of potassium. It causes the following ECG changes: flat or inverted T waves, depression of the S-T segments, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), and ventricular fibrillation (if severe enough). Chapter 11 offers a more complete discussion of ECG interpretation.

4. Bicarbonate (HCO3−)

Altered bicarbonate levels are commonly seen in patients with pulmonary conditions. The kidneys of patients with a chronically elevated arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Paco2) typically retain bicarbonate to moderate the respiratory acidosis caused by the elevated carbon dioxide level. Conversely, the kidneys of patients with a chronically decreased Paco2 level excrete bicarbonate to moderate the respiratory alkalosis caused by the decreased Paco2 level.

6. Glucose

The blood glucose level is important to monitor, because it directly relates to how much glucose is available to the patient for energy for daily activities. The normal values are listed in Table 1-4. Hypoglycemia is a low blood level of glucose; it can mean that the patient is malnourished. Hyperglycemia is a high blood level of glucose; this may indicate that the patient has diabetes mellitus or Cushing’s disease or is being treated with corticosteroids. More specific testing must be done to prove the diagnosis.

4. Complete blood count

a. Review the results of the patient’s complete blood count (Code: IA3) [Difficulty: ELE: R; WRE: Ap]

b. Recommend a complete blood count for additional data. (Code: IC1) [Difficulty: WRE: R, Ap, An]

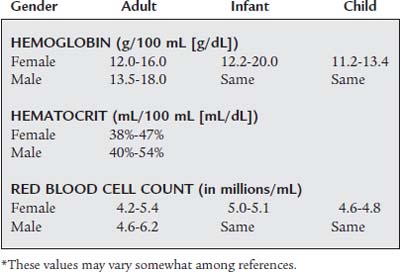

The key normal values for the RBC count are listed in Table 1-5. The hemoglobin and hematocrit values also are important, because they directly relate to the patient’s oxygen-carrying capacity. Decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit values indicate that the patient is anemic. An anemic patient has less oxygen-carrying capacity, and as a result, more stress is placed on the heart during exercise. Hypoxemia resulting from a cardiopulmonary abnormality places this patient at great risk. A transfusion is indicated if the hematocrit is below the level the physician considers clinically safe.

The key normal leukocyte count and differential are listed in Table 1-6. A normal leukocyte count and a normal differential reveal two things about the patient. First, no active bacterial infection is present. Second, the patient’s body is able to produce the normal number and variety of WBCs to combat an infection.

| WHITE BLOOD CELL COUNT (mm3) | |

| Adult | 4,500-11,000 |

| Infant and child | 9,000-33,000 |

| DIFFERENTIAL COUNT | |

| Segmented neutrophil | 40% |

| Lymphocytes | 20% |

| Monocytes | 2% |

| Eosinophils | 0% |

| Bands | 0% |

| Basophils | 0% |

* These values may vary somewhat among references.

A mild to moderate increase in the leukocyte count is called leukocytosis. It is seen as a WBC count of 11,000 to 17,000 per cubic millimeter (mm3). Usually, the higher the count, the more severe the infection. A WBC count above 17,000/mm3 is seen in patients with severe sepsis, miliary tuberculosis, and other overwhelming infections. When a patient has an acute, severe bacterial infection, the WBC differential count shows an increased number of neutrophils. Exceptions to this are patients who are elderly, those who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and those with other immunodeficiencies. These patients may have an infection but show only a mildly elevated WBC count.

5. Review the patient’s coagulation study results (Code: IA3) [Difficulty: ELE: R; WRE: Ap]

Coagulation studies are routinely done for many hospitalized patients; for those who are to have surgery; and for those who have or are suspected of having a blood-clotting disorder. Also, many medications speed or slow clotting time (so-called blood thinners). It is important to review a patient’s coagulation studies before drawing a blood sample or performing a procedure that may lead to bleeding. Table 1-7 lists normal coagulation study results. If the patient’s clotting time is increased, the individual is at risk of bleeding. Be prepared to apply pressure to a blood sampling site (especially and arterial one) longer than expected.

| Test Name | Normal Value | Critical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Bleeding time | 1-9 min | >15 min |

| Prothrombin time (PT or Pro-time) | 11.0-12.5 sec; 85%-100% | >20 sec |

| Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) | 60-70 sec | >100 sec |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) | 30-40 sec | >70 sec |

6. Gram stain results, culture results, and antibiotic sensitivity results

a. Review the patient’s Gram stain results, culture results, and antibiotic sensitivity results (Code: IA3) [Difficulty: ELE: R; WRE: Ap]

7. Review the patient’s urinalysis results

A urine sample routinely is taken from every patient admitted to the hospital and from pregnant women and presurgical patients. Much information about the functioning of the kidneys and other metabolic processes can be gathered from the urinalysis results. A urinalysis also is done for diagnostic purposes in patients with abdominal or back pain, hematuria, and chronic renal disease. Table 1-8 lists the normal findings for a urinalysis. Any abnormal findings should be further investigated to discover the cause.

| Test Item | Normal Value |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Clear |

| Color | Amber yellow |

| pH | 4.6-8.0 (average 6.0) |

| Specific gravity | Adult: 1.005-1.030 (usually 1.010-1.025) |

| Newborn: 1.001-1.020 | |

| White blood cells | 0-4 |

| Red blood cells | 0-2 |

8. Review the patient’s pleural fluid study results

If a patient has had a thoracentesis procedure to remove pleural fluid, the fluid is sent to the laboratory for further analysis. The fluid may turn out to be watery, bloody, infected, or lymphatic. See Chapter 18 for a complete discussion of the types of pleural fluids.

MODULE B

2. Recommend radiographic and other imaging studies to obtain additional data (Code: IC2) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

a. Chest radiograph

A chest radiograph should be recommended in the following situations:

d. MRI scan

An MRI scan provides images of body organs without the use of radioactive materials. The images are created when the powerful magnet of the MRI machine is turned on and off, affecting the way hydrogen atoms align within the body. A limitation of MRI is that the patient cannot have any metallic implants. In addition, most mechanical ventilators cannot be used during an MRI scan because the magnetic field will interfere with the unit. Indications for an MRI scan include, but are not limited to, the following:

3. Review the chest radiograph to determine the quality of the imaging (WRE code: IB7a) [Difficulty: R, Ap, An]

b. Patient positioning

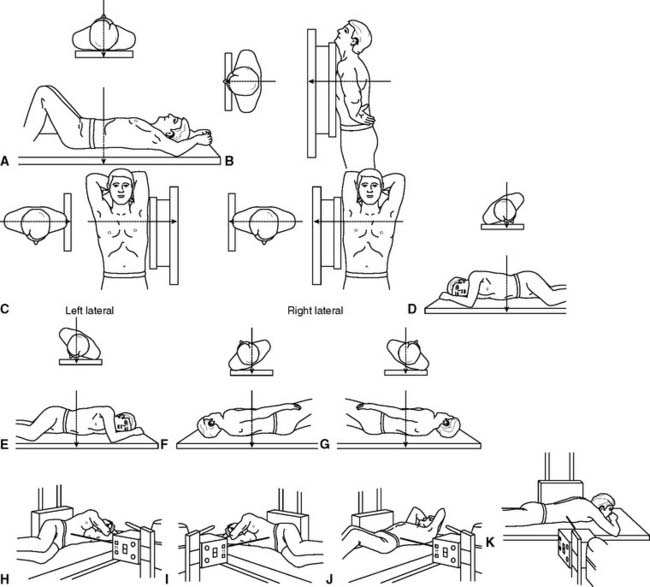

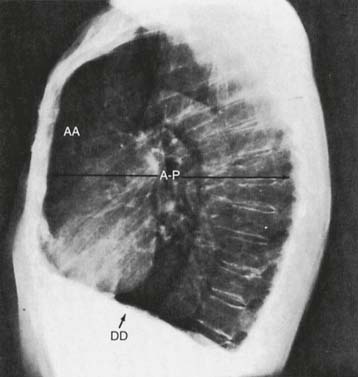

The patient is positioned between the radiograph machine and the film cassette so that the electromagnetic (x-ray) radiation penetrates the patient’s body, hits the film, and provides the desired view of the internal organs. Figure 1-1 shows the most common radiographic projections used for patients with cardiopulmonary problems. Examples of some of these positions are shown in this chapter.

If possible, the patient should be moved to the radiography department, and the chest radiograph should be taken from the posterior to anterior (posteroanterior, P-A, or PA) position. The patient’s chest is placed against the film cassette with the shoulders rolled forward. Because radiographs penetrate from back to front, the size of the heart is close to normal. Normally, the patient is instructed to take in and hold a deep breath. This reveals more clearly the lung fields, heart, and other structures. This may be contrasted with a chest radiograph taken after the patient has exhaled completely. If the patient has been correctly positioned perpendicular to the film cassette, the radiograph image will show the clavicle bones to be symmetrical.

4. Recommend and review the patient’s chest radiograph to evaluate and monitor the patient’s response to respiratory care procedures (Code: IIIE1) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

5. Look for the presence of, or any changes in, pneumothorax (ELE code: IB7c) [Difficulty: R, Ap, An]

a. Pneumothorax

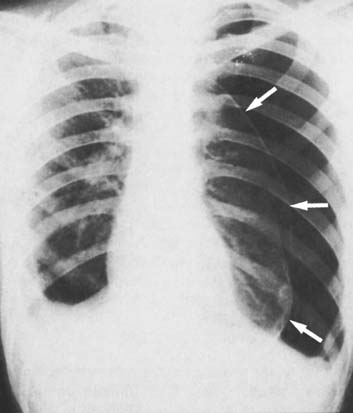

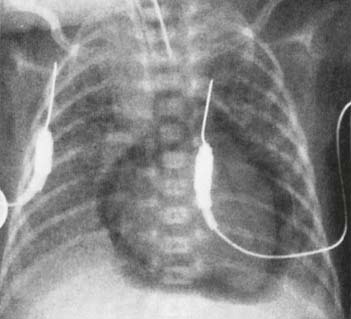

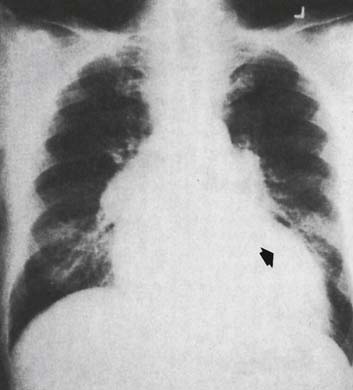

Pneumothorax is air in the pleural space. The lung tends to collapse toward the hilum. A pneumothorax is identified on the chest radiograph as an area of black, indicating air that surrounds the collapsed lung. No lung markings are visible in the air-filled space, and the edge of the lung can be seen (Figure 1-2). If the air is under sufficient pressure to shift the lung and mediastinal structures to the opposite side, the condition is called a tension pneumothorax. This is a serious condition that can lead to the death of the patient if it is not quickly identified and treated. A pleural chest tube is always placed into the affected side to remove the air so that the lung can re-expand.

In addition, the following are other locations where free air can be found:

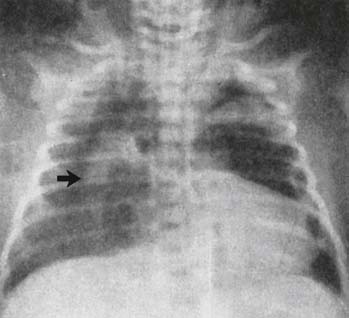

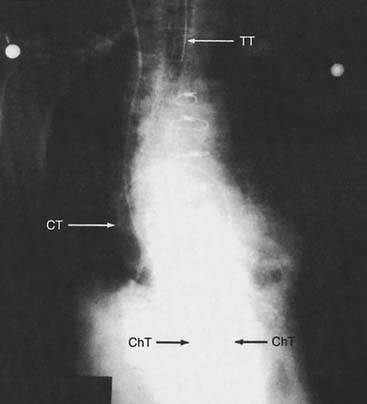

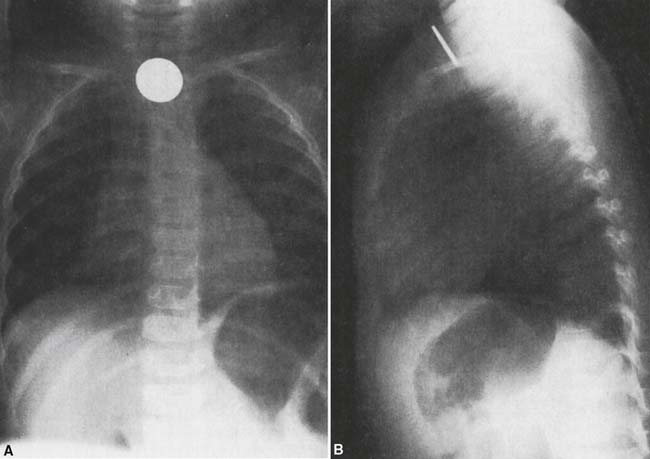

b. Subcutaneous emphysema

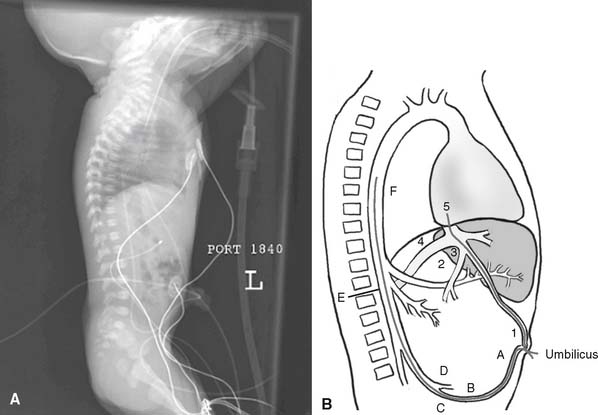

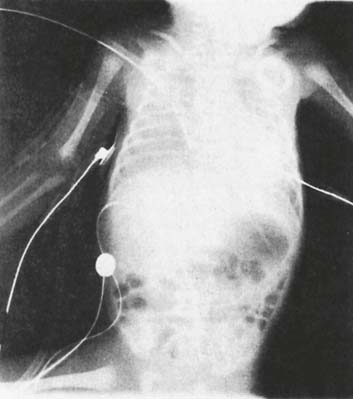

Subcutaneous emphysema is air found in the soft tissues, such as the skin, axilla, shoulder, neck, or breast, of the affected side. In extreme cases, the air forces its way into skin and soft tissues throughout the body. Scattered dark areas (air pockets) appear in the various soft tissues on the chest radiograph (Figure 1-3). Pneumomediastinum is air in the mediastinal space (Figure 1-3). Pneumopericardium is air in the pericardial space (Figure 1-4). Both of these conditions can be very serious. Cardiac tamponade is created if the pressure around the heart is great enough to interfere with its function. Pneumoperitoneum is air in the peritoneal space. This condition can be dangerous in an infant if a large enough volume of air is below the diaphragm and its movement is limited. Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is air that has disseminated throughout the interstitial spaces of the injured lung or lungs. The lungs appear “bubbly” on the chest radiograph (Figure 1-4). The air may further leak into any of the previously listed locations. PIE is most commonly seen in infants with infant respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) who require mechanical ventilation (MV).

6. Look for the presence of, or any changes in, mediastinal shift (Code: IB7f) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

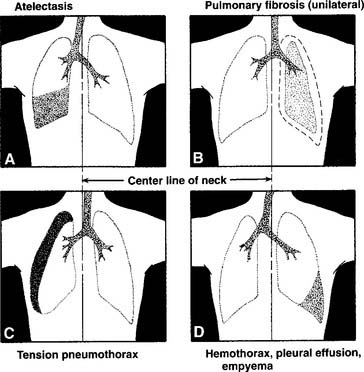

The mediastinum is the area between the lungs that contains the heart and great vessels, trachea, hilar structures, and esophagus. In the neonate, the heart and other mediastinal structures should be approximately in the center of the chest, with the left ventricle to the left of center. In the adult, the majority of the heart and mediastinal structures should be left of center in the chest. A shift of the mediastinum (and heart) is abnormal, as shown in several conditions in Figures 1-2 and 1-5. Either atelectasis or pulmonary fibrosis, if unilateral and great enough, can result in a shift toward the problem area. Tension pneumothorax results in a shift away from the problem area. Fluid in the pleural space, if great enough, results in a shift away from the problem area.

7. Look for the position of indwelling tubes and catheters (Code: IB7d) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Chest tubes are placed to remove any abnormal collection of air or fluid from the thoracic cavity so that the function of the heart and lungs returns to normal. A pleural chest tube is placed to remove air or fluid from the pleural space (see Figure 1-4). The insertion site and depth of insertion of the tube depend on the patient’s disorder. (See Chapter 18 for more discussion on the placement of pleural chest tubes.)

A mediastinal or pericardial chest tube is placed to remove air or fluid from either of these spaces (see Figures 1-4 and 1-6). Cardiac tamponade can result from the pressure of either air or fluid compressing the heart. Most postoperative open-heart surgery patients have one or more mediastinal chest tubes in place for several days to remove any blood from around the heart. The insertion site is below the sternum, and the tube or tubes are placed posterior to the heart in the pericardial or mediastinal space or both.

The various venous catheters (pulmonary artery catheter, central venous pressure [CVP] catheter, umbilical artery catheter [UAC], and umbilical vein catheter [UVC]) should be seen on the chest radiograph from their insertion points to their end points. (See Figures 1-6 and 1-7 for the placement of several catheters.)

8. Look for the presence of, or any changes in, consolidation (ELE code: IB7c) [Difficulty: R, Ap, An]

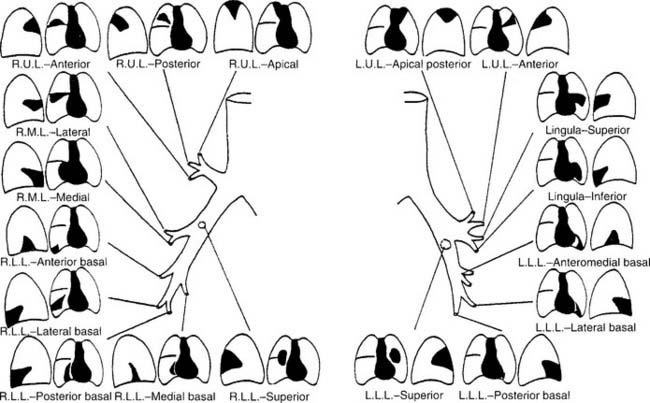

A consolidation is a filling of the alveoli with fluid from a pulmonary infiltrate, aspirated vomitus, blood, or water. It is often segmental or lobar. A pulmonary infiltrate occurs when blood plasma (water) passes from the pulmonary vascular bed into the lung tissues. Usually this fluid moves into the lung, because the alveolar capillary membrane is damaged. On a chest radiograph, an infiltrate often appears as a faint white blurring of the lung and other associated structures. Consolidation is noticed on the chest radiograph as a dense white shadow, because fluid has completely replaced the air. The mediastinum and heart are seen in their normal locations. Figure 1-8 shows a PA and lateral chest radiograph, indicating consolidation in each of the segments of both lungs. Air bronchograms also may be noticed on a radiograph that reveals consolidation.

9. Look for the positions of, or any changes in, the hemidiaphragms (Code: IB7f) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

10. Look for the presence of, or any changes in, pleural fluid (ELE code: IB7c) [Difficulty: R, AP, An]

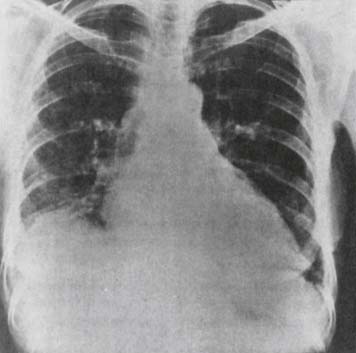

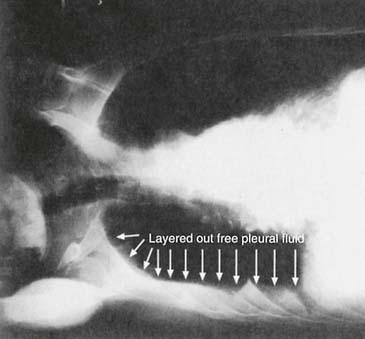

Pleural fluid typically is shown on a PA or AP film as obscuring the costophrenic angle. This is because gravity tends to draw the fluid to the lowest level. Often this results in an obscuring or a blunting of the costophrenic angle of the affected side (Figure 1-11). In some cases, an air/fluid level is seen within the intrapleural space. The term meniscus is used to describe the upward curve seen in the fluid part of this intrapleural air/fluid level. Small amounts of fluid sometimes can be better visualized by taking a lateral decubitus radiograph. If the fluid is able to move freely in the pleural space, it shifts in a few minutes to the lower side (Figure 1-12). An empyema that is loculated (fixed) by adhesions does not move when the patient lies on his or her side. If large amounts of fluid are removed by a thoracentesis procedure, a chest radiograph should be taken to confirm the removal of fluid, the re-expansion of the lung, and that a pneumothorax did not result.

11. Look for the presence of, or any changes in, pulmonary edema (ELE code: IB7c) [Difficulty: R, Ap, An]

Pulmonary edema appears on a PA or AP chest radiograph as fluffy, white infiltrates in either or both lung fields. These tend to be seen more extensively in the lower lobes as a result of gravity pulling the fluid to the basilar vessels, where it leaks out. If the root cause is left ventricular failure, the vessels in the hila also are engorged, and the left ventricle is enlarged (Figure 1-13). A worsening problem results in more fluid leaking into the lungs and the appearance of more white infiltrates on succeeding chest radiographs. Once the problem has been corrected, the lungs return to normal as the fluid is reabsorbed and removed.

12. Look for the presence of any foreign bodies (Code: IB7e) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

A foreign body is anything that is not naturally found in the chest. Metallic objects (e.g., bullets or swallowed or aspirated coins or metal buttons) are easily noticed, because they completely block any radiograph penetration through the chest and are clearly outlined on the film as solid, white shadows (Figure 1-14). Nonmetallic foreign objects (e.g., plastic pieces from toys and foods, such as peanuts) are much more difficult to identify, because they have about the same densities as normal body tissues. Determining the exact location of a foreign body may require taking PA, lateral, and oblique chest radiographs. Lung volumes can be compared by taking inspiratory and expiratory films. A CT scan may be the most successful method of finding a nonmetallic foreign body.

13. Check the chest radiograph for the position of the patient’s endotracheal or tracheostomy tube (Code: IB7b) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

The distal ends of these tubes should be seen within the lumen of the trachea and about midway between the larynx and the tracheal bifurcation to the right and left mainstem bronchi (see Figures 1-4 and 1-6 for endotracheal tube placement). The proximal end of the tracheostomy tube (or transtracheal oxygen catheter) is seen on the film coming out of the surgical insertion site in the suprasternal notch. The distal end should be centered within the trachea above the carina (see Figure 1-6). All these tubes are made of a radiopaque material or have a line of radiopaque material embedded in them so that they can be easily seen on the radiograph.

14. Check the chest radiograph for a sign that the cuff on the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube is overinflated

A properly inflated cuff fills the space between the tube and the patient’s trachea so that an airtight seal is made. If the cuff is overinflated, it places excessive pressure on the trachea. This can cause it to dilate and be seen as a wider dark area than the rest of the tracheal air column. If this is noticed, the cuff pressure should be measured. Excessive pressure should be reduced to a safer level.

16. Look for the presence of, or any changes in, atelectasis

Atelectasis is the collapse of alveoli; no air is found in them. This problem is commonly seen postoperatively in the lower lobes of patients who have had abdominal or thoracic surgery and who do not breathe deeply because of pain. The radiograph of atelectasis shows an increase in lung markings and a decrease in the lung volumes. If it is one sided, the mediastinum may shift toward the affected side (see Figure 1-5, A). If it is bilateral, the mediastinum is properly located. If it is severe enough, the lungs appear a uniform white (Figure 1-15).

MODULE C

1. What is the patient’s level of consciousness or sedation? (Code: IB5a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

c. Semicomatose

d. Comatose or coma

Another common way to evaluate a patient’s level of consciousness is to use the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). With this scale, a range of 3 to 15 points is possible; the larger the total number, the more normal the patient. A score of 15 is achieved in a patient normally awake and alert; a score of 3 is found in an unresponsive patient. Table 1-9 presents the details of the scale.

| Test Parameter | Response | Score* |

|---|---|---|

| EYES | ||

| Open | Spontaneously | 4 |

| To verbal command | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| BEST MOTOR RESPONSE | ||

| To verbal command | Obeys command | 6 |

| Moves arms to painful stimulus of knuckles against sternum | Localizes pain | 5 |

| Flexion—withdrawal | 4 | |

| Flexion—abnormal movement (decorticate rigidity) | 3 | |

| Extension—abnormal movement (decerebrate rigidity) | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

| BEST VERBAL RESPONSE (MAY AROUSE BY PAINFUL STIMULUS IF NECESSARY) | ||

| Oriented and converses | 5 | |

| Disoriented and converses | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words used | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 | |

| No response | 1 | |

* The total is obtained by adding the scores in all three areas. The range is 3 to 15.

From Teasdale G, Jennett B: Management of head injuries, Philadelphia, 1981, FA Davis.

2. Is the patient oriented to time, place, and person? (Code: IB5a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

3. What is the patient’s emotional state? (Code: IB5a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

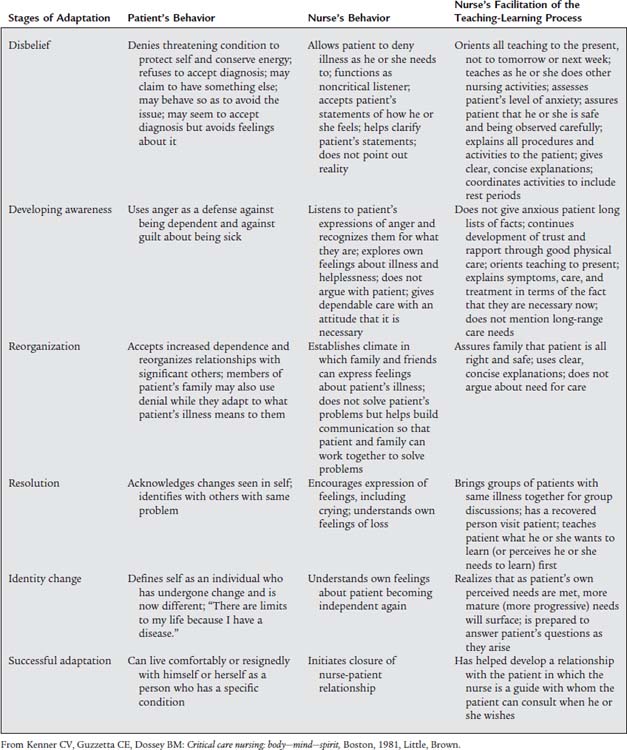

Chronic illness has been approached by a number of authors from varying points of view. Table 1-10 gives a presentation of a patient’s reaction to chronic illness. Substitute “respiratory therapists” for “nurses” as needed.

A patient’s statements and actions that indicate the developing awareness state of adaptation include the following:

5. Does the patient complain of dyspnea? (Code: IB5c) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Box 1-1 classifies the degrees of dyspnea, and Table 1-11 lists different kinds of dyspnea, including orthopnea. Only class I is normal dyspnea (on severe exertion). Classes II to V are progressively severe and limiting for the patient. Any orthopnea is abnormal, and the more the patient must sit up to breathe, the more limited the patient.

BOX 1-1 Degrees of Dyspnea

Modified from Burton GG: Practical physical diagnosis in respiratory care. In Burton GG, Hodgkin JE, editors: Respiratory care: a guide to clinical practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1984, JB Lippincott.)

TABLE 1-11 Causes of Dyspnea Related to Preferred Body Position

| Type of Dyspnea | Clinical Correlations |

|---|---|

| Orthopnea (must sit up to breathe; often occurs at night as paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea) | Congestive heart failure |

| Obstructive sleep apnea (periodically stops breathing, particularly when lying on back) | Obesity; obstructive sleep apnea syndromes |

| Emphysematous habitus | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) |

| Platypnea | Pleural effusion; dyspnea associated with various body positions |

| Orthodeoxia | Pulmonary fibrosis; improvement in dyspnea when patient lies flat |

From Burton GG: Patient assessment procedures. In Barnes TA, editor: Respiratory care practice, Chicago, 1990, Mosby.

The following are examples of questions to ask in evaluating dyspnea:

The following are examples of questions to ask in evaluating orthopnea:

6. What is the patient’s sputum production like? (Code: IB5c) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

a. Time of maximal and minimal expectoration

b. Quantity

MODULE D

1. Evaluate the patient’s general appearance (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

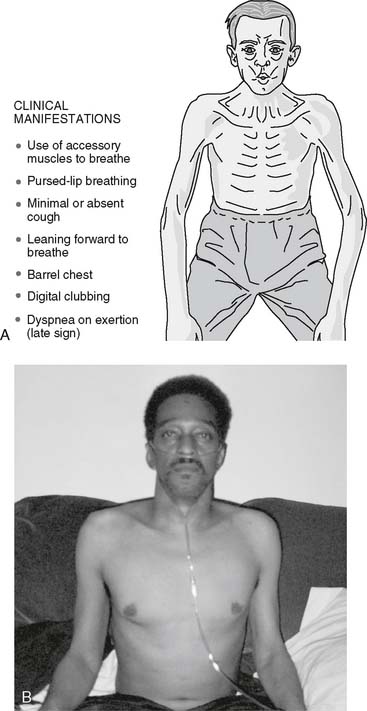

Start by quickly inspecting the patient from head to toe, including how he or she is dressed and found in the room. Ideally, this is done without the patient knowing that he or she is being observed. The patient who does not have cardiopulmonary disease should be able to lie flat in bed or on either side without any breathing difficulty. The patient with one-sided lung disease may prefer to lie with the good side down. This might be the case with lobar pneumonia, pleurisy, or broken ribs. The patient with severe airway obstruction, as seen in asthma, bronchitis, or emphysema, tends to sit up in a chair or on the edge of the bed and use locked arms and shoulders for support. This enables the patient to use accessory muscles (Figure 1-16). The patient with orthopnea will not want to lie down flat because of the resulting SOB. This is commonly seen in patients with congestive heart failure and pulmonary edema.

2. Determine whether the patient is cyanotic (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap: WRE: An]

Cyanosis is an abnormal blue or ashen gray coloration of the skin and mucous membranes. It is most easily seen in white persons by looking at the lips and nail beds. It can be seen in darker pigmented people by looking at the inner portion of the lip, the inner portion of the lower eyelid, and the nail beds. Commonly, cyanosis is said to be caused by hypoxemia, and that the more bluish a patient’s color, the more hypoxemic he or she is. This often is the case, but cyanosis is not an accurate measurement of a patient’s oxygenation. To be safe, a patient with cyanosis should have an arterial blood gas sample drawn for Pao2 measurement or a pulse oximetry (Spo2) measurement performed to evaluate oxygenation.

4. Determine whether the patient has clubbing of the fingers (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

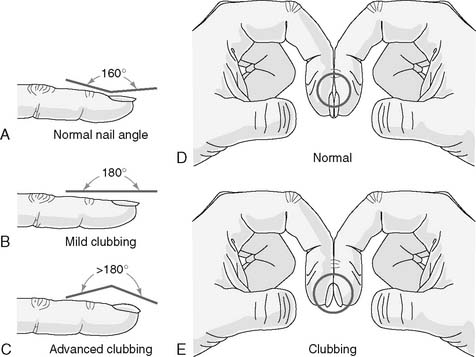

Clubbing of the fingers (also known as digital clubbing) is an abnormal thickening of the ends of the fingers. It also can occur in the toes. The key finding is an angle of more than 160 degrees between the top of the finger and the nail when seen from the side. Clinically, you will notice both a lateral and an AP thickening of the ends of the fingers (Figure 1-17 shows a comparison of normal fingers and clubbed fingers). The fingernail and toenail beds may be cyanotic.

5. Determine whether the patient has edema (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Peripheral edema is most commonly seen in patients with congestive heart failure and those who have a fluid overload. Patients with septicemia often have peripheral edema because the blood-borne pathogen (usually Staphylococcus) causes abnormal capillary leakage.

Many patients with edema from heart failure also have excessive venous distention of the neck veins. The internal jugular vein and external/anterior jugular vein are observed in the normal patient by having him or her lie supine with the head elevated 30 degrees. The crest of the vein column should be seen just above the border of the mid-clavicle. Make a rough measure of the intravascular volume and CVP by pressing on the veins at the base of the neck. The returning blood should fill the veins and make them distend (Figure 1-18). When the pressure is released, the veins should return to their previous level of distention just above the level of the mid-clavicle. Increased venous distention is noted when the veins stand out at a level above the clavicle. This is seen in patients with right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale), cardiac tamponade, fluid overload, and COPD and when high airway pressures and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) are needed for mechanical ventilation. The more the veins are distended, the more the patient is compromised.

6. Determine the patient’s chest wall movement (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

Normal infants and adults have symmetrical chest movement when breathing at rest or during exercise. All breathing efforts are best observed when the patient is sitting up straight or standing erect and shirtless. Ideally, look at the patient from the front, back, and both sides to see the symmetry. In female patients, it may be necessary to observe only the uncovered back to judge chest movement. Any kind of asymmetrical chest movement is abnormal. The asymmetrical movement may result from an abnormality of the chest wall or abdomen or from a pulmonary disorder.

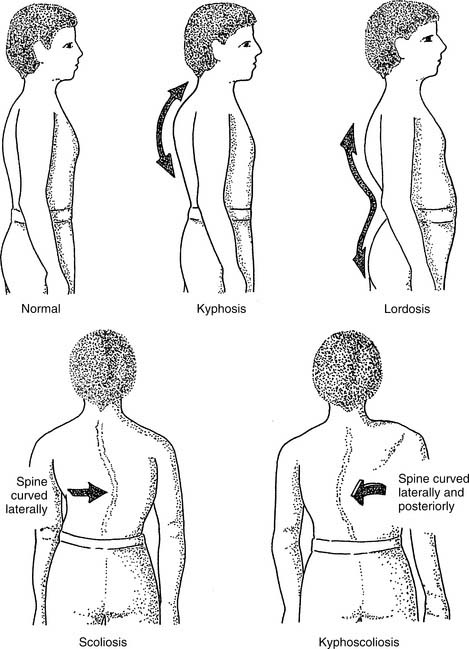

a. Thoracic scoliosis or kyphoscoliosis

Figure 1-19 shows the back view of a patient with thoracic scoliosis or kyphoscoliosis. The patient with scoliosis in Figure 1-19 tends to have more chest movement on the right side because of the right spinal curvature. The left side of the chest and left lung would inflate more than the right if the spine curved to the left. These same findings are seen in a patient with kyphoscoliosis.

c. Pneumothorax

The side with the collapsed lung does not move as much as the chest wall over the normal lung (see Figure 1-2).

d. Atelectasis/pneumonia

The side with the atelectasis or pneumonia does not move as much as the chest wall over the normal lung (see Figure 1-5).

Normally, an adult’s diaphragm moves downward several centimeters toward the abdomen during inspiration as the chest wall moves outward. This is seen when the abdomen protrudes as its contents are forced forward. The chest and abdomen should rise and fall together during quiet and vigorous breathing efforts. In two conditions, this normal chest and abdominal movement does not occur.

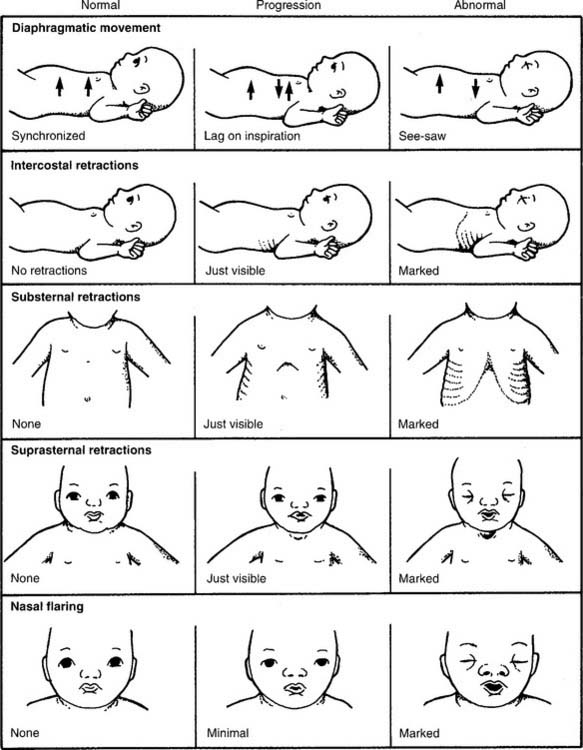

Second, the normal movement does not occur in any condition in which airway resistance is increased or lung compliance is decreased. The greater negative intrathoracic pressure needed to draw the tidal volume into the lungs can cause the chest wall to collapse inward as the abdominal contents are displaced outward. The result is a kind of “seesaw” or paradoxical movement relation between the chest wall and abdomen. On inspiration, the chest wall may move inward as the abdomen moves outward. Patients with RDS typically demonstrate this because the premature neonate’s rib cage is relatively compliant compared with the stiff lungs (Figure 1-20).

7. Determine whether the patient uses accessory muscles when breathing (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

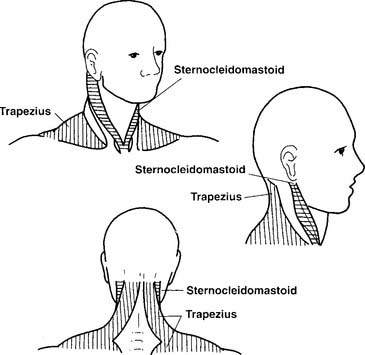

Accessory muscles of respiration should not be needed during passive, resting breathing. They are normally used when a person is breathing vigorously during exercise. A dyspneic patient likely will use them even when resting; this indicates that the WOB is greatly increased. The primary accessory muscles of inspiration are the intercostal, scalene, sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and rhomboid muscles. The abdominal muscles are used during active expiration. The easiest accessory muscles of inspiration to observe in action are the sternocleidomastoids from the front and side of the patient and the trapezius from the back of the patient (Figure 1-21). Their use is not specific for any one condition but is commonly seen in an adult patient with emphysema (see Figure 1-16).

Contraction of the dilator nares muscles (so-called nasal flaring) during inspiration further opens the nasal passages. A person breathing comfortably should have little or no nasal flaring. A person who is exercising vigorously may show nasal flaring in an attempt to reduce airway resistance. Nasal flaring is abnormal in a patient resting in bed, and it is a sign of increased work of breathing, especially in a neonate. Examples of conditions in which nasal flaring is seen include RDS (see Figure 1-20), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and any condition in which pulmonary compliance is decreased or airway resistance is increased.

Intercostal retractions are noticed when the soft tissues between the ribs are drawn inward during inspiration as the chest wall moves outward. Suprasternal retractions are noticed when the soft tissues above the sternum are drawn inward during an inspiration as the chest wall moves outward. Substernal retractions are noticed when the soft tissues below the sternum are drawn inward during an inspiration as the chest wall moves outward (see Figure 1-20). Conditions in which retractions are seen include RDS, ARDS, pulmonary edema, pneumonia, asthma, bronchitis, and emphysema.

8. Determine the patient’s breathing pattern (Code: IB1a) [Difficulty: ELE: R, Ap; WRE: An]

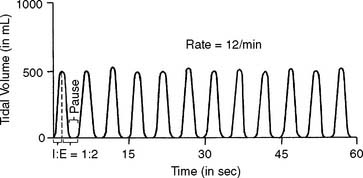

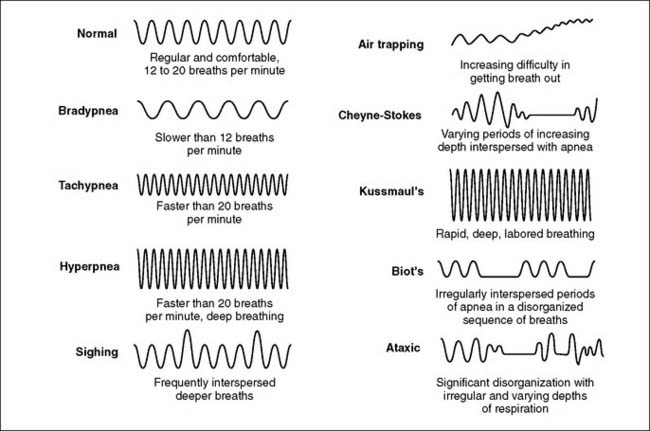

The various respiratory patterns can be identified by their characteristic respiratory rate, respiratory cycle, and tidal volume. Figure 1-22 shows a normal adult breathing pattern, and Figure 1-23 shows examples of normal and abnormal breathing patterns.

Figure 1-23 Representative drawings of normal and abnormal respiratory patterns.

(Modified from Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JE, et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 6, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)