Objectives

• Adapt and apply teaching-learning theory to the critical care setting.

• Perform a learning needs assessment.

• Construct a teaching plan for patients in the critical care unit.

• Discuss four methods of instruction and the appropriateness of each to the critical care setting.

• Describe informational needs of families of critically ill patients.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Adult Learning Principles

Central to successful implementation of an education plan in the critical care and telemetry environment is the incorporation of the principles of adult learning theory.1 Adults must be ready to learn, having moved from one developmental or educational task to the next. They need to know why it is important to learn something before they can actually learn it. Inherent in their attitudes is a responsibility for their own decisions. Consequently, they may resent when others try to force different beliefs on them. Adults bring a wealth of experience to the learning environment that must be recognized and promoted in educational techniques. Because their orientation to learning is life centered, the tasks being taught should focus on current problem resolution. Finally, motivation for the adult learner arises out of internal pressures such as self-esteem and quality of life.

Teaching-Learning Process

The teaching-learning process is a dynamic, continuous activity (Box 3-1). Teaching is not just the passing of facts and information from one person to another. Learning is both growth and development. It is an active process that occurs internally over time and cannot be forced. Learning involves altering behavior to produce changes in one or more of the three learning domains: knowledge, attitudes, and skills.2

Assessment

Assessment is the gathering of information for the purpose of identifying actual or potential learning needs. It identifies gaps in the knowledge, attitudes, and skills the patient or family has regarding the illness, environment, or lifestyle (Box 3-2). Knowing this information will allow the nurse to develop a collaborative, individualized, need-targeted education plan of care. The assessment process does not stop after the completion of the admission assessment; it is continuous and ongoing.

Patients and families may be so overwhelmed by what they see or have already been told that they may be unable to identify their own learning needs. The bedside nurse is responsible for involving both the patient and the family in the assessment process and discovering what they want and need to know. Involving patients and families in this needs assessment process gives value to their needs and assists them in gaining some control over a situation in which they may feel powerless. Active participation and control stimulate the motivation to receive information, as well as make the overall education process more satisfying; in essence, the patient/family will learn more.

Assessing ability, willingness, and readiness to learn is an essential part of developing and implementing an education plan of care. Readiness to learn is the motivation to try out new concepts and behaviors.3 The ability to learn is the capacity of the learner to understand, pay attention, and comprehend the material being taught. Willingness to learn describes the learner’s openness to new ideas and concepts. Several factors affect ability, willingness, and readiness to learn as well as the ability to cope and adapt to the current situation. These factors include physiological, psychological, sociocultural, financial, and environmental aspects.2–4

Development of Education Plan

The education plan must be ongoing, interactive, and consistent with the patient’s plan of care and education level (Box 3-3). Information gathered from the assessment must be analyzed and used to prioritize educational needs, formulate a nursing diagnosis, and develop an education plan of care. The nurse also must consider the patient’s clinical and emotional status when setting education priorities. The education plan should include (1) expected outcomes, (2) objectives, (3) content to be taught, (4) interventions, (5) available educational materials, and (6) appropriate teaching strategies. Refer to the Nursing Management Plan for Deficient Knowledge (Appendix A, p. A-15).

Establish Education Phases and Priorities

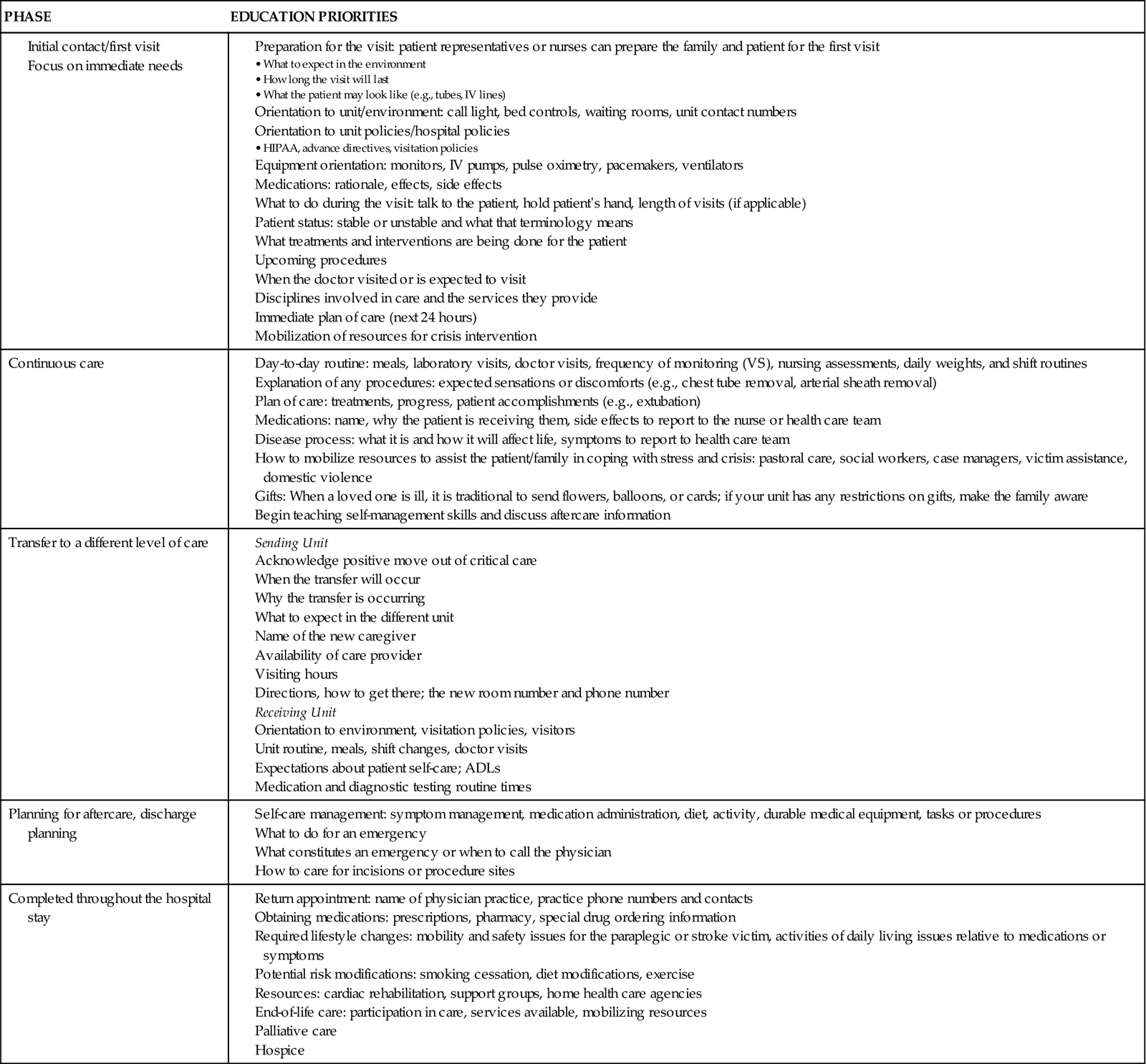

It can be a difficult task to prioritize the multitude of learning needs that practitioners are required to address during a period in acute care. Learning needs in the intensive care unit (ICU), the progressive care, or the telemetry setting can be separated into six different categories to help set teaching priorities in each phase of the hospitalization (Table 3-1). Learning needs during the initial contact or first hours of hospitalization can be predicted. Education during this time frame should be directed toward the reduction of immediate stress, anxiety, and fear rather than future lifestyle alterations or rehabilitation needs. The plan should focus on survival skills, orientation to the environment and equipment, communication of prognosis, procedure explanations, and the immediate plan of care.

TABLE 3-1

EDUCATION PHASES AND PRIORITIES

As the hospital length of stay increases, patients and families begin to adapt to the situation and learning needs change. The patient/family develops positive feelings of relief and happiness in the fact that survival has been achieved. Because lower-level, physiological needs are met, the patient’s efforts can be concentrated on modifying behavior to meet higher-level needs such as self-concept and self-actualization. Teaching during the continuous phase of nursing care is aimed at answering patient or family questions about the treatment plan or how the acute illness will impact their day-to-day lives. Education on lifestyle modification and self-management skills should be presented during this phase of nursing care. Discharge planning is also part of the education process and should start with admission to the hospital. Instructions for home health care, also known as aftercare, should be provided before the day of discharge to avoid decreased retention of education that occurs with information overload.

Teaching Methods

There are three basic methods of teaching: lecture, discussion, and demonstration. The selection of the methods will be determined by various factors, including patient clinical status, readiness to learn, cognitive abilities, learning style, instructional time, and availability of teaching materials and resources. In addition, innovative methods of teaching and presentation of educational materials must be developed and used efficiently to maximize existing resources.5

Lecture

Lecture is the presentation of information in a highly structured format to a group. In this method the teacher provides a great deal of material but may not provide ample opportunities for teacher-learner interaction. This style of teaching is inappropriate for acutely ill patients in the critical care unit, although it may be useful in the telemetry unit. Optimally, the group size should be arranged to enable the learners to ask questions and receive appropriate feedback on content presented.

Discussion

Discussion is less structured than lecturing and allows an exchange and feedback between the teacher and learner. The teacher can adapt the material to meet the needs of the individual or group. Discussion groups can be effective with hospitalized patients when a group with similar problems and at similar stages of adaptation can be gathered. Individual discussion with patients/families is appropriate and valuable during the acute phase of illness because it allows them to express their feelings and interpretations.

Demonstration and Practice

Demonstration involves acting out a procedure while giving appropriate explanations to provide the learner with a clear idea of how to perform a task. Patients can then practice the skill and can be given feedback about their performance. This method is often used in the acute care setting, as when coughing/deep breathing or taking one’s own pulse is taught.

Other Methods of Instruction

In addition to the three basic methods, several other approaches are available to deliver or augment information in a patient teaching program. These methods include commercially prepared or custom-designed printed materials, bedside videotape programs, and computer-assisted patient education programs.

Written Materials

Written materials can be very useful tools in patient/family education. These materials allow repetition and reinforcement of content and provide basic information in printed form for reference later. To be useful, however, the content must be accurate and current, and the patient/family must be able to read and understand it.

Low literacy levels are considered to be a barrier to successful patient/family education and the teaching-learning process.6 Typical patient education materials are written at or above the eighth-grade or ninth-grade reading level and may be out of reach for many people.3,7 Almost 20% of the U.S. adult population has low literacy skills and reads at or below the fifth-grade reading level.8 To help overcome the problem of low literacy and improve health literacy, it is recommended that patient education materials be written at or below the fifth-grade reading level7,9 (Box 3-4).

Audiovisual Media

Using media devices can be an excellent method of instruction. Use of overhead projectors, slides, pictures, videos, and closed-circuit patient education TV channels are the most frequently used audiovisual media strategies. These methods entertain the learners and provide them with important information they should know. This type of media can provide “nice to know” information as well as “need to know” information. Viewing a video alone does not ensure retention of material or knowledge acquisition. Patient education channels and videos should not replace nurse interaction and should be used jointly. The nurse must review with the learner the content presented to reiterate key points and evaluate the outcome.

Closed-circuit television (CCTV) is a common service in many health care settings. CCTV is best used as one component of a comprehensive educational program and is not intended to be used alone. CCTV allows for viewing of the session at a time that best suits the patient/family and can be stopped, restarted, or repeated as necessary.

Computer-Assisted Instruction

Computer-assisted instruction (CAI) is new in the patient/family education arena. Although personal computers are now commonplace, this learning medium may not be suitable for some individuals because comfort levels with technical aspects of the computer vary. The learner must pay attention to the material being presented and must not be preoccupied with learning how to use the computer mouse. Many computer systems available to the general public for learning purposes have touch screens that are easy to use and do not depend on the learner being familiar with computers. These CAI programs are generally easy to use, self-directed, and presented in a pleasant, colorful format.

Internet Websites

Patients and families often use Internet websites to research information regarding the illness or condition of concern. Websites contain a wealth of information, but not all the information is accurate. The nurse can and should play a role in assisting patients in selecting websites and evaluating the content they contain. Strategies may include explaining the difference between commercially supported sites versus sites maintained by the government or professional organizations; asking the patient to print out and bring in such material so that it can be discussed; or simply asking the patient what they may have learned through the Internet and ensuring the information is accurate.10

Implementation of Education Plan

Patients in the critical care environment are educated in many informal interactions with the nurse, and the knowledge gained fosters patient understanding and well-being. Educational opportunities can be present during various nursing care activities, such as bathing and administration of medication. Each encounter with the patient/family must be viewed as a teachable moment. At times during the hospitalization, however, more formal or structured educational experiences may be required.

Learning Environment

As discussed, patient barriers to learning are related to physiological, emotional, and motivational factors. To structure a successful teaching-learning experience in a critical care area, the nurse must also carefully assess the environmental and iatrogenic barriers that affect the interaction. Bright lights, unpleasant odors, unfamiliar noises, and untidy surroundings can distract patients and add to cognitive impairment. Control of these factors can facilitate the learning process. Factors that cannot be controlled must be explained to the patient to alleviate anxiety and facilitate a trusting relationship between patient and nurse.

Keys to Successful Patient Education

Clinical practice today is characterized by increasing patient acuity and a focus on decreasing length of stay, leaving little time for providing patient education. The nurse may only have a few days to provide education for a patient/family about the patient’s illness and ongoing care, therefore it is imperative to use every learning opportunity efficiently and effectively. Several strategies can enhance the education process.11

Get the Patient’s Attention

The nurse must ensure that the information presented is perceived by the patient as important and necessary to know, relevant, and valuable to recovery from illness. Whether using a teachable moment, creating a written teaching tool, or using a visual aid, the topic should be clearly stated at the very beginning. The importance of the information being presented can be communicated to the patient by varying the tone of voice used to emphasize key points. Using assorted teaching tools—discussion, demonstration, pictures or diagrams—will help focus the patient on essential information. Finally, turning abstract theory into meaningful information can be accomplished by using examples familiar to the patient.

Stick to the Basics

Use simple, everyday language when teaching. Avoid the use of medical terms. Avoid trying to teach everything all at once. Identify three or four key points the patient needs to know and focus on those. The nurse can always reinforce teaching by providing supplemental material the patient can review when their condition improves.

Make the Most of Your Time

Teachable moments occur throughout daily patient care—while bathing, administering medications, or taking vital signs. If the family is present in the room, involving them in the teaching process can be beneficial in reinforcing content. Verbal teaching can be supplemented with printed or recorded materials that can be reviewed by the patient and family later.

Reinforce Learning

Provide positive rewards when the patient demonstrates understanding. Be sure to provide documentation when the patient is transferred so that education supplied can be reinforced as the patient progresses.

Evaluation

What to Evaluate

The evaluation process helps the nurse determine the effectiveness of patient/family education interventions. The nurse must decide how well the learner has met the expected outcomes and objectives. Evaluation should be done as each intervention is carried out to allow the nurse to give feedback to the patient/family and revise the education plan of care to accommodate continued learning needs. It is also important to assess the patient/family’s response to the process. The response to the teaching-learning interaction includes the level of interest, willingness to learn, and level of participation.

How to Evaluate

There are several ways to determine the effectiveness of the teaching-learning process. Evaluating knowledge can be done through verbal questioning or written testing on the topic. Questioning provides an interactive avenue for the nurse to assess whether the learner has retained the information taught. Verbal questioning should occur not only immediately after the teaching event but also later to assess knowledge retention. Some CAI programs include a posttest that provides participants with immediate feedback on their learning. Written tests may also be administered to assess knowledge retention but are infrequently used in the critical care setting.

Observation and return demonstration represent the evaluation of choice for the skills-learning domain. For the patient/family to be “checked off” on a particular skill, they should be able to perform it independently, using the nurse only as a resource for questions. Endotracheal suctioning, placing condom catheters, and performing dressing changes are common tasks that patients and families may be asked to learn. Because of the increasingly complex care patients now require at home after discharge, these skills may be the entire focus of teaching before discharge.

It is important to remember that not every teaching moment is a success, and the nurse should not have feelings of guilt or failure when the learner has not achieved the desired objective. Revisiting and revising the goals and objectives during the teaching-learning session may be necessary to meet the ever-changing needs of the patient or family.

Documentation

Documentation of the teaching-learning process is multifaceted and should reflect each component in the education plan of care. Whenever a teaching-learning encounter has been completed, the interaction, material taught, and learner response must be recorded.12 The assessment documentation should include assessment of patient/family learning needs, abilities, preferences, and readiness to learn as well as potential barriers to learning. The remainder of the documentation should include the expected outcome/goals, objectives, interventions, who was taught, what was taught, materials used, patient/family response to teaching, and any follow-up education or materials needed.

Special Considerations

The Older Adult

As individuals age, cognitive, physiological, and psychological changes occur that must be considered when planning and implementing a teaching plan. It is the nurse’s responsibility to understand the effects of aging and adjust teaching strategies to accommodate them.13

Cognitive Effects of Aging

Cognitive effects include processing information more slowly, a decrease in the ability to take in multiple messages, and difficulty understanding the abstract. When teaching the older adult, nurses should provide information slowly and deliberately to allow the patient time to process each concept. Information should be presented in two to three essential points and reviewed frequently. Nurses should avoid using vague terms such as “several times a day” or “until better”. Instead, they must be very specific with amounts, times, and frequencies.

Physical Effects of Aging

Presbyopia, cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration affect the vision of many older adults. Although additional lighting is necessary, it is also necessary to avoid direct sunlight, harsh lights, and using glossy paper. Colors in the blue end of the spectrum are difficult for the older adult to distinguish because of yellowing of the lens of the eye. When using written instructions or color-coded dosing, blues, greens, and purples should not be used.

High-pitched tones become more difficult to hear as an individual ages. Female nurses will need to make an effort to modulate their voices into the lower register so the older adult can hear better. In addition, careful enunciation of words containing higher-pitched sounds like “f”, “s”, “k”, and “sh” may be necessary. Providing audio and video recordings will help reinforce learning.

Aging and associated co-morbidities may result in fatigue, joint pain, or decreased dexterity. Learning can be facilitated by scheduling teaching sessions early in the day, keeping sessions short, and managing pain prior to learning.

Psychological Effects of Aging

Older adults often suffer from depression. Learning can be enhanced by selecting content that holds value and relevance to the individual. Nurses should choose content that is perceived by the learner as important in maintaining quality of life, and should try to relate what they are teaching to the individual’s previous life experiences.

Sedated and Unconscious Patients

Patient education should not be reserved for the conscious and coherent patient only; it should be provided to the unconscious or sedated patient as well. Addressing the learning needs of this critically ill population of patients is challenging. These patients cannot communicate their educational needs, nor can they interact and participate in the learning process. Although it is truly not known what the unconscious or sedated patient hears or remembers, it is known that some sedated patients undergoing surgery remember discussions that took place among physicians and staff during the procedure. Therefore, one should not ignore unconscious or sedated patients during the education process. These patients may not be able to respond or participate, and the effectiveness of the teaching process cannot be evaluated, but providing information regarding environment, procedures, sensations, and time of day is benevolent and may help to decrease immediate physiological stress.

The Illiterate Patient

Illiteracy affects 44 million people in the United States and may be difficult to diagnose.14 The nurse must be aware of the subtle signs, such as avoiding reading or asking others to read and complete forms, or becoming defensive when handed written materials during teaching. If the patient is illiterate, using simple language, providing frequent examples and using teach-back or return demonstration can be useful in providing patient education. Pictures, diagrams, and audio or videotapes can also be useful for these patients.

The Noncompliant Patient

Noncompliance, or an unwillingness to learn, does not necessarily mean that the patient is consciously choosing not to participate in their care or follow medical instructions. There are many other issues that can lead to noncompliance. The nurse must be alert for barriers that may prevent a willing patient from being compliant. Box 3-5 lists factors that may contribute to noncompliance or unwillingness to learn.15

Using an Interpreter

The patient/family with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) presents a challenge for the nurse in providing education. In addition to the basics already presented, more preparation is required to ensure a productive teaching session. Box 3-6 describes helpful techniques when using an interpreter for patient education.16

Informational Needs of Families in Critical Care

Family members and significant others of critically ill patients are integral to the recovery of their loved ones. When planning for the overall care of patients, nurses and other caregivers need to consider the informational and emotional support needs of this group.17 Families of critically ill patients report their greatest need is for information.17 Flexible visiting hours and informational booklets regarding the critical care experience are recommended to meet this need.18

Preparation of Patient/Family for Transfer from Critical Care

When patients are more stable, requiring less hemodynamic monitoring and close observation, they are frequently transferred to another level of care in a different geographic hospital setting. They may be transferred to an intermediate care unit (also called step-down, intermediate care area, or telemetry). While on these units, patients receive optimal care to their level of requirement, a lower nurse-to-patient ratio, and less expensive technological monitoring in a quieter environment.19,20

Being transferred from the critical care unit to a step-down unit may cause the patient anxiety and stress. By this time, patients and families have become dependent on the monitors, equipment, constant nursing attention, and abundant information received while in the critical care unit. The patient has become secure knowing that immediate physiological and emotional needs are being met. A strong bond has often developed between the staff and the family. Many patients and families are reluctant to give up that bond and believe that their needs will not be met as well on a step-down unit. To avoid anxiety and provide the patient and family with some control over the event, nurses need to prepare them for the transfer process.

Preparation for transfer should start after the patient has been stabilized and the life-threatening event that resulted in hospitalization has subsided. The stressor at this point is not the now-familiar critical care environment but the unfamiliar step-down environment. Information such as where the patient will be transferred, the reason for transfer, and the name of the nurse who will be providing care should be given as soon as known. Before transfer, information about changes in care, expectations for self-care, and visiting hours should be provided to the patient/family. Family members should also be contacted concerning exactly when the patient will be transferred so they can be present during the transfer or made aware of the patient’s new location.

The education plan of care and tips learned by the critical care staff about that particular patient and family should be communicated to the step-down unit staff. Most of the patient transfers made from the critical care unit to a step-down unit are planned events. At times, however, unplanned or unexpected transfers occur, usually when the critical care unit requires bed space for a more seriously ill patient. In this situation the transfer occurs quickly, either during the day or often at night. Families may be present in the hospital or may have gone home for the evening. This sudden need to transfer the patient can produce as much anxiety as the initial event, primarily because the patient/family may not feel ready for the transfer or may think they have lost control of the situation. Providing the patient/family with concrete evidence of improvement, such as more favorable vital signs or the need for fewer medications or tubes, can assure them of improvement in the patient’s condition before unplanned transfers occur. Increased communication and providing consistent information to patients and families also increases satisfaction with care and services.21,22