Patient and Family Education

Challenges of Patient and Family Education

When alterations in health arise in daily life, people use all available resources to discover information to help them cope and adapt to the new experience. This type of consumerism has developed a populace that is more educated in health matters than ever before. It is our duty as health professionals to assist patients and families with information gathering and self-care management skills so they can lead lives of the best quality possible. According to The Joint Commission, patients must receive “sufficient information to make decisions and to take responsibility for self-management activities related to their needs.”1 The goals of patient and family education are to improve health outcomes by promoting healthy behavior and involvement in care and care decisions.1

Admission to a critical care unit usually is an unexpected event in anyone’s life. The seriousness of the situation and unfamiliarity of the hospital or unit environment evokes a stress response in patients and their families. Nursing care is focused on improving the patient’s physiologic stability and promoting end-organ tissue perfusion. Promoting the most basic human physiologic survival need for cellular oxygenation is the priority. Alterations in normal functioning related to disease-process progression, sedation, assist devices, or mechanical ventilation contribute to the possibility of mental alterations in the patient. Sleep deprivation and sensory overload add to the complexity of the issues that affect the patient’s ability to receive and understand medical information. Mental alterations may limit the effectiveness of the teaching-learning encounter. These physical and cognitive limitations prevent patients from receiving or understanding information related to their care and impair their ability to make an informed decision.2 At these times, critical life-or-death care decisions are transferred to a proxy, usually an immediate family member. The designated proxy has the responsibility to make informed treatment decisions for the patient. These types of situations present the nurse with special challenges in the education of patients and families.

Critical illness disrupts the normal patterns of daily life. Stress and crisis can develop within the family unit and stretch its members’ coping resources.3 These many emotional factors build barriers to the teaching-learning process and can become frustrating for the learner and the nurse. Amid the chaos, how do bedside nurses effectively provide patient and family education that can optimize outcomes and deliver quality, cost-effective care? It is the nurse’s responsibility to educate himself or herself about concepts that provide insight into the framework for patient and family education. Adult educational concepts such as adult learning principles, types of educational needs, barriers to learning, stress and coping strategies, and evidence-based interventions must be used to develop an individualized education plan to meet the identified learning needs of the patient and family.

Education

Definition

Patient education is a process that includes the purposeful delivery of health-related information to promote changes in behavior that will optimize health practices and assist the individual in attaining new skills for living.4,5 This concept can be overwhelming in the fast-paced, technology-rich setting of the critical care environment. The bedside nurse must incorporate the abundant educational needs of the patient or family into the education plan and be aware of the requirements of regulatory agencies and the legalities of documenting the teaching-learning encounter.

Benefits

Studies have documented that quality education shortens hospital length of stay, reduces readmission rates, and improves self-care management skills.4–6 Complications associated with the physiologic stress response may be prevented if the patient or family perceives the education encounter as positive. Positive encounters decrease the stress response, relieve anxiety, promote individual growth and development, and increase patient and family satisfaction.4–6 The following are examples of positive outcomes associated with a structured teaching-learning process.7,8

• Clarification of patients’ understanding and perceptions of their chronic illness and care decisions

• Improved health outcomes relative to self-management techniques, such as symptom management

• Promotion of informed decision making and control over the situation

• Diminished emotional stress associated with an unfamiliar environment and unknown prognosis

• Improved adaptation to stressful situations

• Improved satisfaction with the care received

The Education Process

The education process follows the same framework as the nursing process: assessment, diagnosis, goals or outcomes, interventions, and evaluation.4 Although this chapter discusses these steps individually, in practice, they may occur simultaneously and repetitively. The teaching-learning process is a dynamic, continuous activity that occurs throughout the entire hospitalization and may continue after the patient has been discharged. This process is often envisioned by the nurse as a time-consuming task that requires knowledge and skills to accomplish. Whereas knowledge and skills can be obtained, time in the critical care unit is a scarce commodity. Many nurses believe they cannot educate unless formal blocks of education time are planned during the shift. Although this type of education encounter is optimal, it is not realistic for contemporary nursing. The nurse must recognize that teaching occurs during every moment of a nurse-patient encounter.9 Instructions for how to use to the call bell or explanations of events and sensations to expect during a bed bath can be considered an education session. It is the nurse’s role to recognize that education, no matter how brief or extensive, affects the daily lives of each person with whom he or she comes in contact. By following the nursing process, the physical assessment and education assessment can occur simultaneously.

Step 1: Assessment

According to The Joint Commission, education provided should be appropriate to the patient’s condition and should address the patient’s identified learning needs.1 The assessment is an important first step to providing need-targeted patient and family education. It begins on admission and continues until the patient is discharged. A formal, comprehensive, initial education assessment produces valuable information; however, it can take the nurse hours to complete. The nurse must focus the initial and subsequent education assessments on identifying gaps in knowledge related to the patient’s current health-altering situation.

Learning needs can be defined as gaps between what the learner knows and what the learner needs to know, such as survival skills, coping skills, and ability to make a care decision. Identification of actual and perceived learning needs directs the health care team to provide need-targeted education. Need-targeted or need-to-know education is directed at helping the learner to become familiar with the current situation. Educational needs of the patient and family can be categorized as 1) information only (environment, visitation hours, get questions answered); 2) informed decision making (treatment plan, informed consent); or 3) self-management (recognition of problems and how to respond).5,10 Patient education to be included in the education plan should address the plan of care, health practices and safety, safe and effective use of medications, nutrition interventions, safe and effective use of medical equipment or supplies, pain, and habilitation or rehabilitation needs.1

Learning needs may change from day to day, shift to shift, or minute to minute. Educational needs are influenced by how the patient or the family perceives or interprets the critical illness.11 Perceptions of experiences vary from person to person, even if two people are involved in the same event. This intense internal feeling affects the desire to learn and understanding of the current situation. Satisfaction with the learning encounter is often judged to be positive if the nurse meets the expected learning needs of the patient and family. Congruency between nurse-identified needs and patient-identified needs brings about more positive learning experiences and encourages the learner to seek further information. The nurse must actively listen, maintain eye contact, seek clarification, and pay attention to verbal and nonverbal cues from the patient and the family to gather relevant information concerning perceived learning needs. The nurse should seek to first understand the learning need from the patient’s point of view and then seek to be understood.

Strategic questioning provides an avenue for the nurse to determine whether the patient or family has any misconceptions about the environment, their illness, self-management skills, or the medication schedule. Health care providers use the term noncompliant to describe a patient or family members who do not modify behaviors to the meet the demands of the prescribed treatment regimen, such as following the rules of a low-fat diet or medication dosing. However, the problem behind noncompliance may not be a conscious desire to defy the treatment plan but instead be a misunderstanding of the importance of the medication or how to take the medication. The technique of asking open-ended questions (“Can you tell me what you know about your medication?”) can elicit more information about the patient’s knowledge base than asking closed-ended questions (“You know this is your water pill, right?”). Open-ended questions provide the nurse an opportunity to assess actual knowledge gaps rather than assume knowledge by obtaining a yes-or-no response. These types of questions also assist the patient and family to tell their story of the illness and communicate their perceptions of the experience,5 allowing the adult learner to feel respected and involved in the treatment process. Questions that elicit a yes-or-no response close off communication and do not provide an interactive teaching-learning session. Box 5-1 contains sample questions the nurse can use in an assessment to obtain needed information. Generally, with practice and effort, it can be determined what educational information is needed in a brief period without much disruption in the routine care of the patient. Patients and families are multidimensional. Even with good questioning skills, the nurse cannot assess many aspects of the learner during the initial contact or even during the hospital stay.

Learner Identification

Identifying learner characteristics benefits the nurse and results in optimal communication and the patient’s understanding of information. Certain factors can affect the education process. Culture or ethnicity, age, and adult learning principles influence the manner in which information is presented and concepts are understood.5,12

Family

A family can be defined as a group of individuals who are bonded by biologic, legal, and social relationships.3 The modern family is diverse in ethnic backgrounds, sexual orientation, age, gender, work experience, physical or mental challenges, communication skills, educational backgrounds, work experience, geographic location, lived experiences, and religious beliefs.13–15 A picture of the modern family would resemble that of a large patchwork quilt. Patches of different sizes, ethnicities, religions, cultures, attitudes, stages of development, and lived experiences would overlap and occupy their own individual spaces within the quilt framework. Bedside practitioners are expected to provide culturally competent care to each individual in the critical care setting. Culturally competent care is the delivery of sensitive, meaningful care to patients and families from diverse backgrounds.15 This implies that the practitioner must value diversity and become knowledgeable concerning the cultural strengths and abilities of those for whom they care.16 Communication and understanding impact the education process. Provision of language-appropriate literature and translation services and recognition of cultural or religious differences in the perception of illness and treatment influence the education encounter.15

Age-Specific Considerations

The critical care patient population differs culturally and by age and stages of human development. Older adult patients may have more difficulty reading patient educational materials or the label on the bottle of prescription medication than younger adults. Printed materials with larger fonts may be needed for these patients. Older adults were not exposed to technology during their youth and may find it difficult to navigate the fragmented maze of modern health care. Because of advanced age, this population of adults may have prescriptions for multiple drug therapies. Education to prevent adverse drug reactions may be required because of the prevalence of multiple drug therapies.17 Older adults may also be coping with end-of-life issues and are in need of information to make informed decisions. Young adults may struggle with the issue of how to incorporate intimacy into their lives without feeling isolated from the mainstream social scene. The need for privacy and peer support may be required to assist the young adult in coping with the current situation. The practitioner must recognize these age-specific issues and incorporate them into the education plan.1

Adult Learners

Adults learn in large part through lived experiences. The motivation to learn is internal and problem-oriented, focusing on life events. Malcolm Knowles described these principles of adult learning in a model known as andragogy. Adult learning theory stresses concepts of individualism, self-assessment, self-direction, motivation, experience, and autonomy. Adults tend to have a strong sense of self-concept, are goal-oriented learners, and like to make their own decisions.18 They take responsibility and accountability for their own learning and want to be respected as individuals, as well as recognized for accomplished life experiences. Adults have individualized learning styles and often lack confidence in their ability to learn. Education is resisted when the information given is perceived to be in conflict with the individual’s self-image.

The learning process generally involves altering some part of current behavior to produce changes in lifestyle, incorporating the new or chronic illness into daily living. Coping mechanisms such as anger, disbelief, and denial affect the willingness of the patient or family to learn. The unwillingness to change behavior to manage health needs adds to the complexity of the critical care teaching-learning encounter. The nurse must provide need-to-know information in easy, understandable terms and in short bursts. Positive feedback and repetition of information may also be required before health education is incorporated into the patient’s or family’s bank of experiences.18 Adults are sensitive about making mistakes and tend to view mistakes as failures. Learning situations that the patient and family interpret as belittling or embarrassing or that are perceived as insurmountable will be avoided or disregarded. The nurse should act more as a coach or facilitator of information instead of a didactic instructor.12 The teacher can only show the learner to the door; the learner must decide to walk through that door. Learning is an active process that occurs internally over time and cannot be forced. Bedside nurses are obliged to be proactive and to have a good understanding of adult learning theory and to incorporate its concepts into the assessment of learning needs, development of an education plan, implementation of the plan, and evaluation of the outcomes of the education encounter.

Factors Affecting the Learning Process

Information must also be gathered on factors that affect the education process and impair the ability of the patient or family to respond. These factors include 1) desire and motivation; 2) physical or cognitive limitations; 3) cultural and religious views of illness or health; 4) emotional barriers; and 5) barriers to effective communication.1

Readiness, Willingness, Ability

For teaching to be successful and learning to be achieved the patient or family must be ready, willing, and able to learn. The ability to learn is the capacity of the learner to understand, pay attention, and comprehend the material being taught. Willingness to learn describes the learner’s openness to new ideas and concepts. Readiness to learn is the motivation to try out new concepts and behaviors.5 Even if the inventive teaching methods, well-considered education materials, and amounts of time are unlimited, learning cannot take place if the patient or family is not ready, willing, and able to learn.19 Several factors affect the ability, willingness, and readiness to learn, as well as the ability to cope and adapt to the current situation. These factors include physiologic, psychologic, sociocultural, financial, and environmental aspects.5,12

Physiologic Factors

Physiologic alterations in heart rate and blood pressure can be measured and taken into consideration during the teaching-learning encounter.3 Sources of physiologic stress in the critically ill include medications, pain, hypoxia, decreased cerebral and peripheral perfusion, hypotension, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, infection, sensory alterations, fever, and neurologic deficits.12 Experiencing one or more of these stressors may completely consume all the patient’s available energy and thoughts, affecting his or her ability to interact, comprehend, and respond to teaching.

Health Literacy

Patients and families may be ready and willing to learn but lack the ability to comprehend and act upon the information presented to them. In its report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion the Institute of Medicine (IOM) states that nearly half of adult Americans struggle to understand and follow the health information they are provided. The IOM defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” However, health literacy goes beyond the individual. Practitioners must develop the ability to present information and instructions in a way that patients and families can best understand.20

Assessing health literacy is not an easy task, but knowing what to look for can make it easier. Several tools are available to assist health care professionals to screen for low literary skills. Generally, these tools fall into four categories: 1) word recognition; 2) reading comprehension; 3) functional health literacy; and 4) informal methods.21,22 Each tool has both positive and negative aspects to its use.

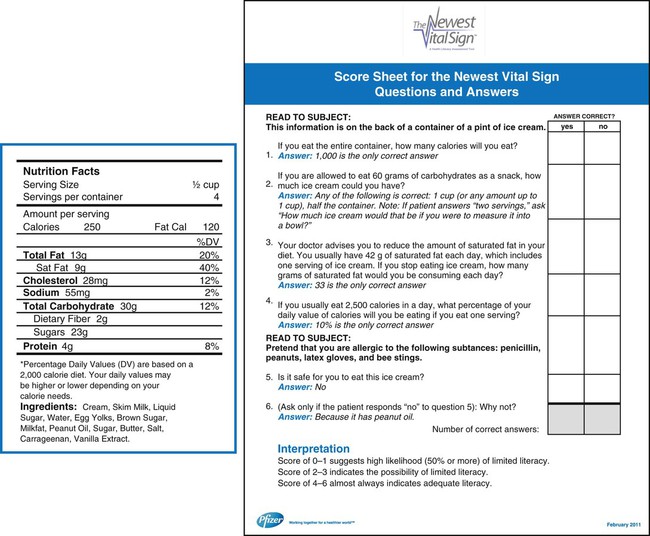

Functional health literacy tests assess the individual’s level of comprehension and ability to put into action what they have learned. Examples of these tests include the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA)4 and the Newest Vital Sign (NVS).21–22 The TOFHLA requires the individual to complete missing sections of written statements to assess the ability to read and comprehend directions for taking medications, monitoring blood glucose, and keeping appointments.23 The tool takes 20-30 minutes to administer and score, making it undesirable for use in the critical care setting. An abbreviated version, the S-TOFHLA, is now available. It takes approximately 10-12 minutes to complete and score. Figure 5-1 shows the NVS tool and scoring sheet.

Shame has been cited as one of the most common emotions associated with low health literacy.24 Behaviors such as handing a form to a family member to complete, claiming to be too tired, or “forgetting” their glasses are a few behaviors that may be used by individuals to hide their limitations. Other behaviors that may also provide clues to a patient’s health literacy are listed in Box 5-2.

Sociocultural Factors

Variables such as culture, ethnicity, values, beliefs, lifestyle, and family role influence the way an individual perceives illness, pain, and healing.15 Culturally sensitive educational strategies should be developed to communicate specific needs to other members of the health care team and achieve optimal learning outcomes.1

Psychologic Factors

When confronted with life-altering situations such as admission to a critical care unit, patients and families may experience anxiety and emotional stress. Anxiety and fear disrupt the normalcy of daily life. Sources of emotional stress include fear of death, uncertain prognosis, role change, self-image change, social isolation, disruption in daily routine, financial concerns, and unfamiliar critical care environment.3,20 These intense emotions can lead to a crisis situation and alter the ability of the patient and family to cope.25,26 During the critical illness, an individual’s ability to process or retain information and ability to participate in the treatment plan could be altered.2 If the disease process or physiologic stressors impair the patient’s ability to make decisions, the burden of decision making will transfer to the family. Gender differences affect a patient’s reaction to stress. For example, women who have experienced a myocardial infarction report higher anxiety levels than men at all points during the hospital stay.27 Physiologic alterations caused by anxiety negatively impact the recovery process and the long-term prognosis.27 In critical situations, the nurse may find it necessary to repeat information or limit teaching sessions to short bursts rather than one long encounter. Medical jargon should be limited and replaced by terms that are easy to understand. Provision of honest and accurate disease state information may decrease the effects of stressors and alleviate anxiety and fear.

Coping

Coping refers to the way a person manages stressful events that are straining or exceeding personal resources.5,28 The stressful event is appraised according to the level of threat to the individual and is managed by focusing on the problem at hand or the emotions felt at the moment.29 Critical illness disrupts the normalcy of daily routines. Coping strategies are used by the patient and family to help maintain control over the situation and encourage hope and stability in life. Disbelief and denial may be present any time during the hospitalization. Phrases such as “Why me” and “I can’t believe this is happening” are common in the critical care setting. Other coping mechanisms, such as denial and anger, hamper the ability of the patient or family to problem solve and cope with the situation. All are barriers to the ability of the patient to receive information and incorporate it into the self-concept. Adults must be physically ready and emotionally willing to learn. Teaching new skills or self-management techniques to the adult learner therefore presents a special challenge to the nurse in critical care. For example, until the patient accepts the diagnosis of heart failure as part of who he or she is, he or she will not make appropriate changes in lifestyle to avoid an exacerbation of the disease.

Adaptation

A stressor can be any condition, situation, or perception that requires an individual to adapt.30 All situations in a critical care facility may well be considered stressful. The capacity of an individual to adapt is paramount in breaking down emotional barriers that affect willingness and readiness for learning. Culture, beliefs, attitudes, and ability to mobilize resources affect a person’s ability to respond to a crisis situation.28 General characteristics of the stages of adaptation to illness are outlined in Table 5-1 with corresponding applications for the teaching-learning process. Patients and families move through these stages on an individual timeline and at a variable pace. A person may move back and forth between stages and may skip one altogether. The patient and each member of the family may be experiencing different stages in the adaptation process at the same time. The education encounter may need to be modified to meet the needs of the patient and family.

TABLE 5-1

TEACHING-LEARNING PROCESS IN ADAPTATION TO ILLNESS

| STAGE OF ADAPTATION | CHARACTERISTIC PATIENT RESPONSE | IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING-LEARNING PROCESS |

| Disbelief | Denial | Orient teaching to present. |

| Teach during other nursing activities. | ||

| Reassure patient about safety. | ||

| Explain all procedures and activities clearly and concisely. | ||

| Developing awareness | Anger | Continue to orient teaching to present. |

| Avoid long lists of facts. | ||

| Continue to foster development of trust and rapport through good physical care. | ||

| Reorganization | Acceptance of sick role | Orient teaching to meet patient. |

| Teach whatever patient wants to learn. | ||

| Provide necessary self-care information; reinforce with written material. | ||

| Resolution | Identification with others with same problem; recognition of loss | Use group instruction. |

| Use patient support groups and visits by recovered patients with same problem. | ||

| Identifying change | Definition of self as one who has undergone change and is now different | Answer the patient’s questions as they arise. |

| Recognize that as basic needs are met, more mature needs will arise. |

Environmental Factors

The critical care environment can be considered a source of stress to the learner. Although sounds, people, and state-of-the-art equipment are familiar and mundane for the nurse, this environment may appear foreign and intimidating to the patient and family. Prior exposure to a critical care unit is a double-edged sword. Depending on whether the outcome of the experience was positive or negative, it may help alleviate or heighten anxiety. The nurse must pay attention to the perceptions of the environment by the patient and family and alter the teaching-learning encounter accordingly. Sleep cycle alterations caused by sleep deprivation or sensory overload related to continuous noise from machines or people affect the patient’s ability to concentrate and comprehend information. Allowing frequent uninterrupted rest periods assists the patient in obtaining structured sleep.30

For patients and families to value education, they must believe the information source is reliable. The bedside nurse is the most available source of information in the critical care unit. It is important for him or her to develop a rapport and establish a sense of trust within the nurse-patient relationship. These positive characteristics are recommended for a supportive learning environment. Assignment of multiple caregivers may negatively affect the ability of the patient and family to form a trusting relationship with the nursing staff. Arranging consistency in the assigned caregivers can help promote rapport and trust, as well as decrease anxiety and enhance comfort level with the environment.5,28

Step 2: Education Plan Development

Education must be ongoing, interactive, and consistent with the patient’s plan of care and education level.1 The nurse must analyze information gathered from the assessment to prioritize the educational needs of the patient and family. The nursing diagnosis for deficient knowledge and accompanying interventions can be applied to any situation. The nurse must also consider the patient’s physical and emotional status when setting education priorities. Ability, willingness, and readiness to learn are factors that impair acceptance of new information and add to the complexity of teaching-learning encounter. These factors should be recognized by the nurse before implementation of teaching. The written teaching plan should identify the learning need, goals or expected outcome of the teaching-learning encounter, interventions to meet that outcome, and appropriate teaching strategies.

Determining What to Teach

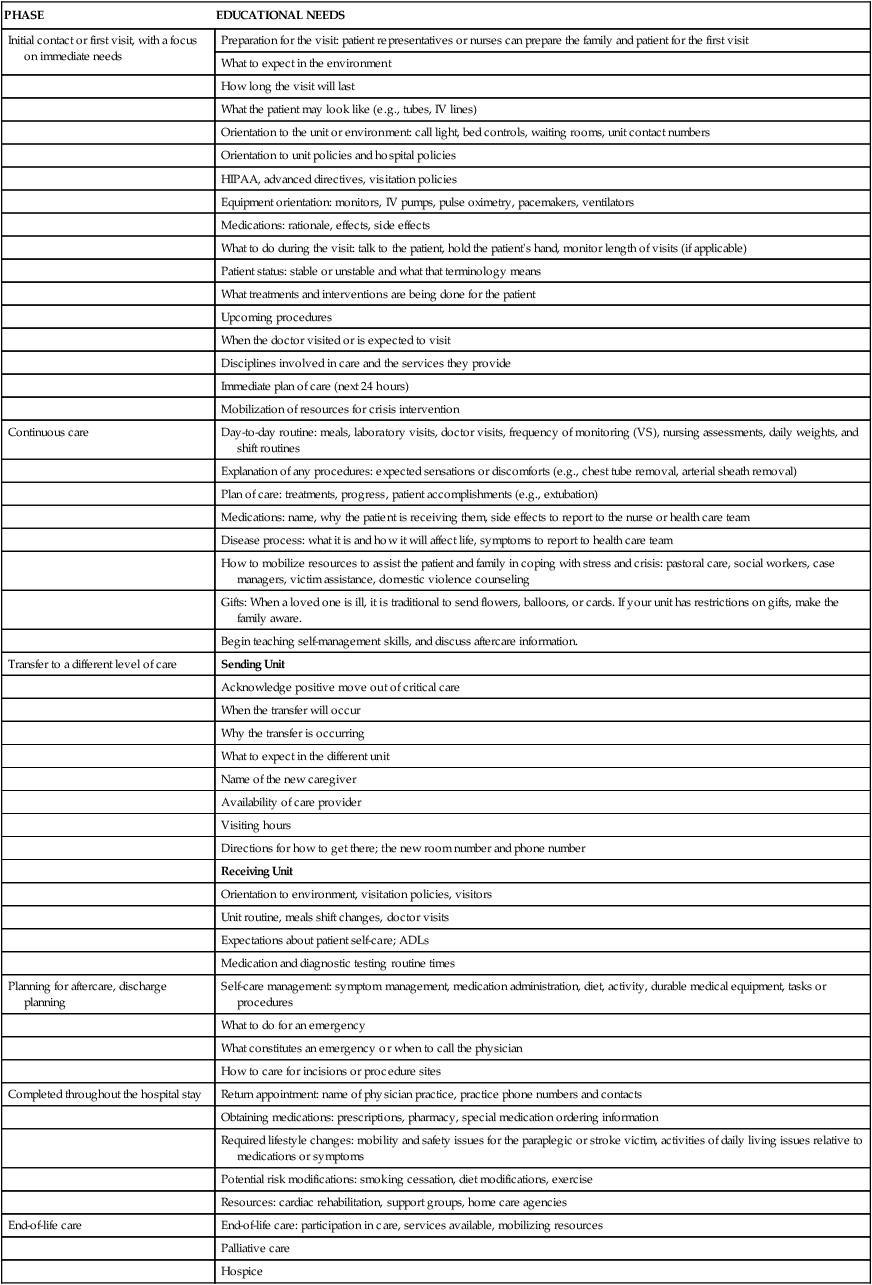

It can be difficult to prioritize the multitude of learning needs that practitioners are required to address during a period in critical care. Learning needs in the critical care unit, the progressive care, or the telemetry setting can be separated into four different categories to help set teaching priorities in each phase of the hospitalization (Table 5-2). Learning needs during the initial contact or first hours of hospitalization can be predicted. Education during this time frame should be directed toward the reduction of immediate stress, anxiety, and fear rather than future lifestyle alterations or rehabilitation needs. Interventions are targeted to promote comfort and familiarity with the environment and surroundings.31 The plan should focus on survival skills, orientation to the environment and equipment, communication of prognosis, procedure explanations, and the immediate plan of care.

TABLE 5-2

CATEGORIES OF EDUCATIONAL NEEDS IN CRITICAL CARE

| PHASE | EDUCATIONAL NEEDS |

| Initial contact or first visit, with a focus on immediate needs | Preparation for the visit: patient representatives or nurses can prepare the family and patient for the first visit |

| What to expect in the environment | |

| How long the visit will last | |

| What the patient may look like (e.g., tubes, IV lines) | |

| Orientation to the unit or environment: call light, bed controls, waiting rooms, unit contact numbers | |

| Orientation to unit policies and hospital policies | |

| HIPAA, advanced directives, visitation policies | |

| Equipment orientation: monitors, IV pumps, pulse oximetry, pacemakers, ventilators | |

| Medications: rationale, effects, side effects | |

| What to do during the visit: talk to the patient, hold the patient’s hand, monitor length of visits (if applicable) | |

| Patient status: stable or unstable and what that terminology means | |

| What treatments and interventions are being done for the patient | |

| Upcoming procedures | |

| When the doctor visited or is expected to visit | |

| Disciplines involved in care and the services they provide | |

| Immediate plan of care (next 24 hours) | |

| Mobilization of resources for crisis intervention | |

| Continuous care | Day-to-day routine: meals, laboratory visits, doctor visits, frequency of monitoring (VS), nursing assessments, daily weights, and shift routines |

| Explanation of any procedures: expected sensations or discomforts (e.g., chest tube removal, arterial sheath removal) | |

| Plan of care: treatments, progress, patient accomplishments (e.g., extubation) | |

| Medications: name, why the patient is receiving them, side effects to report to the nurse or health care team | |

| Disease process: what it is and how it will affect life, symptoms to report to health care team | |

| How to mobilize resources to assist the patient and family in coping with stress and crisis: pastoral care, social workers, case managers, victim assistance, domestic violence counseling | |

| Gifts: When a loved one is ill, it is traditional to send flowers, balloons, or cards. If your unit has restrictions on gifts, make the family aware. | |

| Begin teaching self-management skills, and discuss aftercare information. | |

| Transfer to a different level of care | Sending Unit |

| Acknowledge positive move out of critical care | |

| When the transfer will occur | |

| Why the transfer is occurring | |

| What to expect in the different unit | |

| Name of the new caregiver | |

| Availability of care provider | |

| Visiting hours | |

| Directions for how to get there; the new room number and phone number | |

| Receiving Unit | |

| Orientation to environment, visitation policies, visitors | |

| Unit routine, meals shift changes, doctor visits | |

| Expectations about patient self-care; ADLs | |

| Medication and diagnostic testing routine times | |

| Planning for aftercare, discharge planning | Self-care management: symptom management, medication administration, diet, activity, durable medical equipment, tasks or procedures |

| What to do for an emergency | |

| What constitutes an emergency or when to call the physician | |

| How to care for incisions or procedure sites | |

| Completed throughout the hospital stay | Return appointment: name of physician practice, practice phone numbers and contacts |

| Obtaining medications: prescriptions, pharmacy, special medication ordering information | |

| Required lifestyle changes: mobility and safety issues for the paraplegic or stroke victim, activities of daily living issues relative to medications or symptoms | |

| Potential risk modifications: smoking cessation, diet modifications, exercise | |

| Resources: cardiac rehabilitation, support groups, home care agencies | |

| End-of-life care | End-of-life care: participation in care, services available, mobilizing resources |

| Palliative care | |

| Hospice |

Patients and their families are attempting to cope with the seriousness of the current situation and need information continually to adapt their behavior accordingly. Leske and Molter’s hallmark research in the area of needs of the families of critically ill patients has provided nursing with a scientific body of knowledge for identification of the learning needs of this population. Results of these studies found that families of critically ill patients needed to have their questions answered honestly and to have a feeling of hope.32 The outcomes of this research can be used in developing interventions for the initial phase in the hospitalization process. Box 5-3 includes a sample listing of interventions that can be used to help meet the needs of the family. During this time of elevated stress, the nurse may have to refocus the patient and family to help concentrate efforts on coping with the present instead of dwelling on possibilities of the future. Not addressing these immediate concerns can result in further anxiety, affect the ability to cope, and prevent open and honest communication.3

Writing Goals or Outcomes

An outcomes statement helps clarify to the teacher and the learner what is to be taught, what is to be learned, what is to be evaluated, and what is to be documented. When goals or expected outcomes of the education encounter are clearly stated, the teacher and the learner understand the expectations and will do their best to achieve them. These statements differ from interventions in that they reflect what the learner is to accomplish, not what the nurse is to teach.33 Identifying and writing outcomes may be the most difficult aspect in the development of the education plan of care. The written outcomes provide direction for the teaching-learning process and should be straightforward, attainable, and include one task or learning domain.33

Developing Interventions

Interventions describe how a nurse will become involved in providing education to the patient or the family. Determining education interventions is part of clinical decision making.34 Nurse-initiated interventions are based on clinical knowledge and judgment and have a direct impact on the outcome of the teaching encounter.34 Although physiologic problems occupy most of the nursing plan of care, it is essential to incorporate teaching interventions into the daily plan to create positive patient outcomes. Nurses just entering the profession readily refer to education plans developed by experienced nurses to guide them in their new role of patient educator.35 Carefully planned and developed interventions support nurses, patients, and families focused on achievable outcomes. Education interventions are targeted toward information to be taught, such as how to care and use oxygen or how to recognize signs and symptoms of an infection. The following is an example of a clearly stated research-based intervention: Instruct the patient and family on proper name of prescribed diet.34

Standardized Education Plans

Standardized education plans provide the health care team with consistent outcomes and interventions. Even though standardized plans are easy to implement, they must be individualized to meet the specific needs of the patient or family. Examples of standardized plans of care include patient pathways, traditional nursing care plans for Deficient Knowledge, and the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) for Teaching: Disease Process, which is presented in Box 5-4. Examples of nursing management plans for Deficient Knowledge are included in Appendix A.

Step 3: Implementation

After the assessment is completed and the education plan is developed, need-targeted education can commence. Beginning practitioners differ from experienced practitioners in their skills of implementing the education plan of care. Experienced practitioners use their intuition and knowledge base to anticipate learning needs and form a mental list of interventions and possible outcomes.35 Those just starting in the profession need the concrete education plan that has been developed to guide the teaching-learning encounter.35

Setting up the Environment

The optimal environment for learning is one that is nonthreatening, comfortable, open, and honest. Many factors concerning the critical care environment can be threatening or anxiety producing. The practitioner must assess for these distractions and control them as much as possible. Providing the family with open visitation and access to the patient and health care providers can help decrease their anxiety level and improve satisfaction with care.3 Current Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements for patient confidentiality necessitate a need for privacy during the teaching-learning encounter. Bedside practitioner attention to this detail in open environments such as critical care units, waiting rooms, and emergency departments is important in creating an environment of trust and reassurance. Supportive education promotes behaviors that facilitate motivation to learn and adherence to lifestyle changes.36 The following is a list of strategies the practitioner can implement to facilitate learning36:

• Show empathy and concern. Actively listen to the learner and acknowledge lived experiences and ideas.

• Use language and nonverbal communication to enhance choice and promote problem solving.

• Reduce language that is controlling, criticizing, guilt provoking, judgmental, or punishing.

• Provide rationale for self-management behaviors: the importance of changing lifestyle to manage symptoms.

One example of the difference between supportive education and nonsupportive education is demonstrated by a patient diagnosed with chronic heart failure who is experiencing an exacerbation of symptoms related to dietary salt intake. Suppose the patient states that he or she is doing “okay” at adhering to the low-salt diet, but family members complain that he or she eats too many processed foods and too much take-out fast food. This is an example of a nonsupportive teaching phrase: “You know salt isn’t good for you.”36 This phrase is judgmental, critical, and guilt provoking and makes an assumption of the patient’s level of knowledge. By revising the wording in the phrase, the meaning of the information is changed. This is an example: “I know it is difficult not to eat all of your favorite foods. Adding salt is up to you. Do you understand that salt will affect your heart condition?”36 This supportive statement transfers accountability of performing the self-management skill from the nurse to the patient and motivates the patient to make the conscious decision to limit salt intake.

Teaching Strategies

Discussion

Several strategies are used to maintain a positive teaching-learning encounter:

• Addressing the patient and family members by name

• Clearly stating the purpose of the education encounter

• Getting and keeping them involved in the learning process

• Maintaining eye contact during the encounter

• Keeping the encounter brief and to the point

• Giving positive reinforcement

• Communicating with professionals in other disciplines about the progress and additional learning needs of the patient and family4,5

Written Materials

Written media, such as brochures, pamphlets, patient pathways, and booklets, are common in outpatient and inpatient areas of health care. They usually are inexpensive and offer opportunities for a wide range of education: disease process education, risk factor modification information, procedure education, medication education, and use of medical equipment in the home setting. Written materials address multiple learning styles and offer learner-centered teaching with concrete, basic information that can be placed at the learner’s fingertips for immediate review, as well as future review anytime the learner desires. The practitioner must make sure that written materials are appropriate for the patient population as a whole and for a particular individual patient or family. Several factors should be considered when choosing printed materials for patient education: readability, cultural considerations, age-specific considerations, primary language, and literacy.6

Readability is an important factor in the consideration of printed educational materials. Readability refers to how easy or hard the literature is to read. Nearly 20% of the U.S. adult population have low literacy skills and read at or below the fifth-grade reading level.37 Typical patient educational materials are written at or above the eighth- or ninth-grade reading level and may be out of reach for many readers.5,38 If the patient or family is unable to read the material or understand its meaning, he or she cannot perform self-management tasks to maintain health. This sets the patient and the family up for failure and being labeled noncompliant.

Readability tools are designed to provide quick and easy assessment of the readability level of patient educational materials. However, it is important to know that these formulas do not assess the understandability of the material. Many formulas, such as the Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) and the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) assessment tools, are available to assist practitioners in determining the readability of health educational materials. Selection of the appropriate readability formula is dependent on the type of information being presented. Additional tools maybe found at www.readabilityformulas.com.

Providing written educational materials at the appropriate reading level is important, if the information is to be easily read and understood by most patients and families. To assist the nurse in overcoming literacy-related barriers to health education, it is recommended that patient educational materials be printed at or below the fifth-grade reading level.37,39 Samples of health-related instructions at different reading levels are provided in Box 5-5.

Several situations present special challenges with regard to the use of printed patient-education materials. The inability of a patient or family to read or understand the English language does not mean they cannot understand directions and treatment regimens. Multilingual, written educational materials are a necessity in any health care institution. Hodgdon states that “communication is 55% visual, 37% vocal, and 7% verbal or the actual message.”40 Including pictures, drawings, diagrams, charts, or tables in educational materials has been shown to enhance understanding and increase retention in patients with low literacy skills.41 Materials translated into Braille or provided in audio format may be used for the blind patient.

When predeveloped educational materials do not meet the needs of the institution’s patient population, the decision is made to develop internal patient educational materials. Producing homegrown educational materials can be time consuming and difficult.12 Time must be spent determining content, readability, and design. Some simple rules when designing written patient-education materials include 1) use a white background; 2) use pictures and graphics to illustrate major concepts; 3) use bullet points instead of paragraphs to reduce reading time and “word clutter”42; and 4) emphasize only key facts and desired behaviors, avoiding the addition of “nice to know” information that may distract the reader from the true message.

Internet Sites

Patients and families often use websites to research information about the illness or condition about which they are concerned.43 Information on the Internet is generally presented on an eighth-grade reading level.9 Websites contain a wealth of information. However, the information is not regulated or controlled for reliability or validity,43 and not all information provided on every website is accurate. The nurse must advise the patient and family about this concern and ask them to print out and bring in such material so it can be discussed. Government websites and those of professional organizations, reputable health care organizations, and consumer health groups offer trustworthy information for the practitioner and the public.43

Communication

Communicating effectively is essential to obtaining positive outcomes for patient education. Speaking slowly, clearly, and avoiding the use of slang or medical jargon is essential. Even when the patient and family speak English, the stress of hospitalization, fear of health outcomes, and difficulty speaking of personal issues with a stranger can present a challenge to providing patient education. When the patient or family has limited English proficiency (LEP) the challenge becomes even greater. In many instances a family member is called upon to serve in the role of interpreter. Although this may seem like an ideal solution, the family member may not have any better comprehension of the material being taught, and thus is unable to adequately relay the information. The use of professional interpreter services is preferable when the message is vital to a patient’s health and well-being. Interpreter services are available through a variety of modes.44 Some hospitals employ professional interpreters or provide special training for multilingual staff in effective interpretation. Telephonic interpretive services are offered by many vendors and special phones with dual handsets are available for use. Emerging technology has given rise to video-on-demand interpretive services such as those offered through the Language Access Network. Whichever method is used, interpretation can be a frustrating process. Box 5-6 describes helpful techniques to enhance the experience.45

All patients and families desire to be understood and have their concerns validated. This can be difficult for patients who are critically ill and whose ability to communicate to family and health care providers is impaired. Communication aids such as picture cards, picture boards, or word boards enhance the ability of the nurse to understand educational needs and communicate information. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems may be considered for temporarily nonspeaking patients in the critical care unit. Technology that has been available in the outpatient setting to help persons who cannot speak is becoming available in the critical care environment. This technology is known as an electronic voice output communication aid (VOCA). VOCA is a prerecorded, human or digitized computer-generated voice message.46 It can be beneficial for patients who are awake and alert but are unable to talk for reasons such as mechanical ventilation through an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy tube. Whole phrases, as opposed to pictures or single words, are communicated to the health care team; for example, “I am having pain.”46 This technology can assist the patient to communicate comfort needs, anxiety, and fears and to ask questions concerning care or progress. Intubated patients describe the inability of families and caregivers to effectively understand their needs as an extremely stressful part of being in the critical care unit.30 AACs can also assist the nurse to evaluate more effectively the outcome of education. Use of verbal, whole-sentence communication rather than traditional, nonverbal picture board communication has been found to decrease the guesswork in interpreting patient needs.46

Special Considerations

The Older Adult

As individuals age, cognitive, physiologic, and psychologic changes occur that must be considered when planning and implementing a teaching plan. It is the nurse’s responsibility to understand the effects of aging and adjust teaching strategies to accommodate them.47

The Noncompliant Patient

Noncompliance, or an unwillingness to learn, does not necessarily mean that the patient is consciously choosing not to participate in their care or follow medical instructions. There are many other issues that can lead to noncompliance. The nurse must be alert for barriers that may prevent a willing patient from being compliant. Box 5-7 lists factors that may contribute to noncompliance or unwillingness to learn.48

Step 4: Evaluation

How to Evaluate

Physiologic evidence of the effectiveness of education can also be measured. Indicators such as blood cholesterol levels, blood pressure, heart rate, blood sugars, and weight can lead the practitioner to the conclusion that the patient and family may be having difficulties understanding or following through with the identified plan of care.36 Adults generally want to comply with new expectations but often cannot for various reasons, such as a lack of money for medications or an inability to understand what is expected of them. These barriers must be explored and included in the education plan.

Step 5: Documentation

Documentation of education is necessary to communicate educational efforts to members of the health care team, patients and families, and regulatory agencies. The nurse should recognize that informal teaching at the bedside is education. It is important to record any information given to the patient on formal documents approved for use by each health care institution. In most institutions, formal education records are used to document education rendered by practitioners of any discipline involved in the care of a particular patient and family. These forms are communication tools used to indicate progress in the teaching-learning process from shift to shift, day to day, and discipline to discipline.49 Documentation should include education from admission to discharge on topics ranging from orientation to the environment to acquisition of self-management skills for home care.

What Should Be Documented?

The complexity of information, demand by governing agencies, lawsuits, and the sheer volume of patients in and out of a unit are driving nurses to provide quality documentation of the education encounter.49 Documentation of the teaching-learning process is multifaceted. The documentation form should “tell the story” of the education encounter from assessment to evaluation. Documentation of the education assessment should include learning preferences; factors that impair ability, readiness, and willingness to learn; and actual or perceived learning needs. Information should be recorded on the interaction, material taught, supplemental materials distributed, response to the education, achievement of outcome, and any follow-up education or resources needed.

Factors that Affect the Teaching-Learning Process

Many factors can produce barriers to a successful teaching-learning process. The physiologic, psychologic, sociocultural, financial, and environmental factors previously discussed are known to affect the patient’s and family’s ability, willingness, and readiness to learn. Physical disabilities, impaired vision, and hearing loss affect the learner’s ability to read materials, listen to instructions, or perform a technical task.50 If a technical task is required, ensure that the patient or family member has the physical ability or manual dexterity to perform the required skill. Provision of eyeglasses and hearing aids is essential to improving participation in learning. Several other factors have an impact on the teaching-learning process5,12:

• Lack of an accurate assessment

• Not involving the patient or the family in the process

• Overloading the learner with information

• Relying too heavily on resources

• Haphazard and nondirected teaching; lack of an education plan of care

• Teaching at the wrong time, hurried teaching, not paying attention to the learner

• Lack of trust and rapport between the teacher and learner

Barriers to the teaching-learning process exist for the patient or family and for the bedside nurse. Time constraints, decreased length of stay, and daily routines interrupt or impair the nurse’s ability to communicate information to the patient and the family. Table 5-3 includes common barriers to the education process experienced by nurses. The patient’s positive interactions and relationships with health care providers, as well as a clear understanding of his or her illness, symptoms, and medications, will promote adherence to the patient education plan.51

TABLE 5-3

| BARRIER | EXAMPLE | SOLUTION |

| Interruptions | Daily routines | Use all available teachable moments. |

| Distractions | Tasks; medication administration | Turn TV off; minimize noise. |

| Phone calls | ||

| TV or other noise in patient’s room | ||

| Night shift | Sleeping patients | Plan education before bedtime. |

| Sedation or pain medications | Narcotic analgesic | Teach before administering the medication. |

| Nurse unaware of what to teach | Diabetic education | Educate self. |

Data from London F. No Time to Teach. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1999; Rankin S, Stallings K. Patient Education: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2001.

Informational Needs of Families in Critical Care

Family members and significant others of critically ill patients are integral to the recovery of their loved ones. When planning for the overall care of patients, nurses and other caregivers need to consider the informational and emotional support needs of this group.52 Families of critically ill patients report their greatest need is for information.52 Flexible visiting hours and informational booklets regarding the critical care experience are recommended to meet this need.54

Preparation of the Patient and Family for Transfer from Critical Care

When patients are more stable, requiring less hemodynamic monitoring and close observation, they are frequently transferred to another level of care in a different geographic hospital setting. They may be transferred to an intermediate care unit (i.e., step-down unit, intermediate care area, or telemetry). While on these units, patients receive optimal care to their level of requirement, a lower nurse-to-patient ratio, and less expensive technologic monitoring in a quieter environment.55–56

Preparation for transfer should start after the patient has been stabilized and the life-threatening event that resulted in hospitalization has subsided. The stressor at this point is no longer the critical care environment but has become the unfamiliar step-down environment. Explanations about where the patient will be transferred, the reason for transfer, and the name of the nurse who will be providing care should be offered as soon as known. Before transfer, information about changes in care, expectations for self-care, and visiting hours should be provided to the patient and family. Family members should be contacted concerning exactly when the patient will be transferred so they can be present during the transfer or made aware of the patient’s new location (Box 5-8).

The education plan of care and tips learned by the critical care staff about that particular patient and family should be communicated to the step-down unit staff. Most of the patient transfers made from the critical care unit to a step-down unit are planned events. However, unplanned or unexpected transfers sometimes occur, usually when the critical care unit requires bed space for a more seriously ill patient. In this situation, the transfer occurs quickly during the day or often at night. Families may be present in the hospital or may have gone home for the evening. This sudden need to transfer the patient can produce as much anxiety as the initial event, primarily because the patient and family may not feel ready for the transfer or may think they have lost control of the situation. Providing the patient and family with concrete evidence of improvement, such as more favorable vital signs or the need for fewer medications or tubes, can assure them about improvement in the patient’s condition before unplanned transfers occur. Increasing communication and providing consistent information to patients and families also increases satisfaction with care and services.57

Summary

• A collaborative, well-organized, need-targeted education plan of care is essential to improving health outcomes and decreasing lengths of stay.

• The teaching-learning process is a dynamic, continuous activity that occurs throughout the entire hospitalization and may continue after the patient has been discharged.

• Information must be gathered on many factors that may affect the education process: cultural or religious views of illness or death, emotional barriers, desire and motivation, physical or cognitive limitations, and barriers to effective communication.

• The learner’s needs can be defined as gaps between what the learner knows and what the learner needs to know (e.g., survival skills, coping skills, ability to make a care decision).

• Standardized education plans provide consistent interventions and outcomes; however, they must be individualized to meet the unique needs of the patient and family.

• The optimal environment for learning is one that is nonthreatening, comfortable, open, and honest.

• Determination of an appropriate teaching strategy is essential to meet the needs of the patient.

• Providing information regarding the environment, procedures, sensations, and time of day is important for patients who are unconscious and may help to decrease immediate physiologic stress.

• When planning for the overall care of patients, nurses must consider the informational needs and emotional support of family members.

• It is important to prepare patients and families for transfers to other units to decrease stress and anxiety related to going to a less intensively monitored environment.