Pathophysiology, clinical features and diagnosis of vascular disease affecting the limbs

Introduction

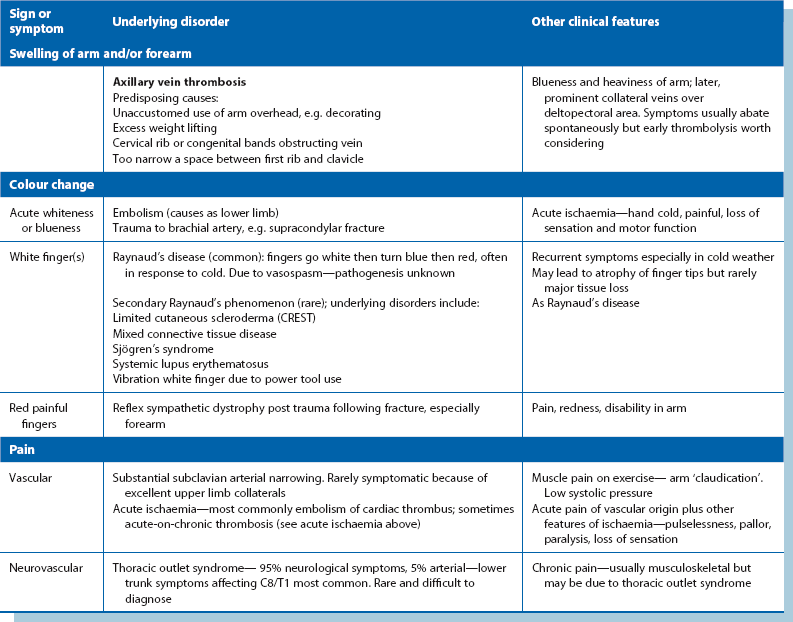

The term ‘peripheral arterial disease’ (PAD) is often employed to mean obstructive (‘obliterative’) disease of major lower limb arteries causing ischaemia. However, a range of vascular disorders can cause symptoms in upper and lower limbs, and a broader term ‘peripheral vascular disease’ (PVD) includes any disease of arteries, veins or lymphatics outside the heart. This chapter concentrates on lower limb vascular-related problems as they are much more common; upper limb symptoms are outlined in Table 40.5 (p. 488).

Vascular insufficiency of the limb (Table 40.1)

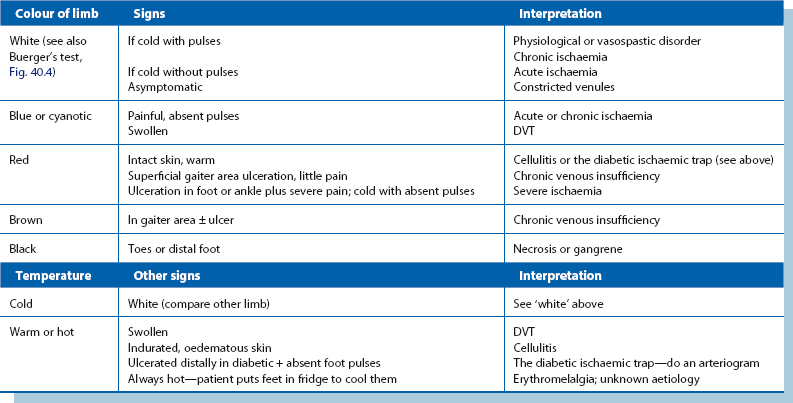

Table 40.1

Pathophysiology of arterial and venous insufficiency—the clinical consequences of vascular diseases affecting the lower limb*

*Aneurysms are covered in Chapter 42 and varicose veins and thrombophlebitis in Chapter 43.

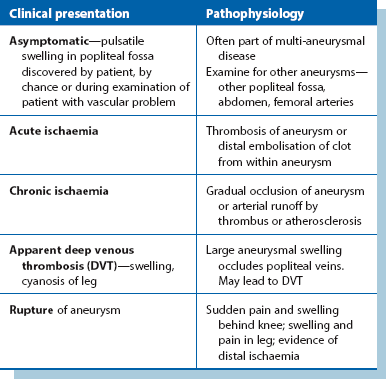

Acute arterial insufficiency means inadequate arterial blood supply to a limb over hours or days. It may be caused by embolism into a normal artery, in which thrombus originating in the heart or other proximal site detaches and is swept distally until it lodges and obstructs the vessel. It can also occur by in situ thrombosis of an atherosclerotic plaque in lower limb arteries, by thrombosis of a popliteal aneurysm or by an aortic dissection extending into the lower limb vessels. Any disorder can manifest in several ways—see Table 40.2 for the various manifestations of popliteal aneurysm.

Symptoms and signs in the limb

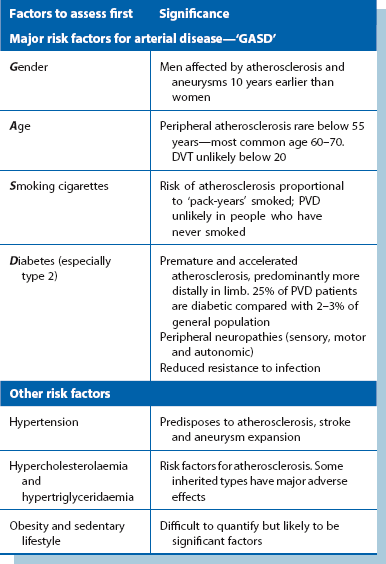

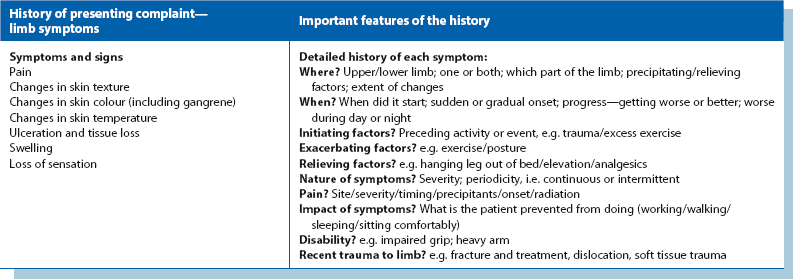

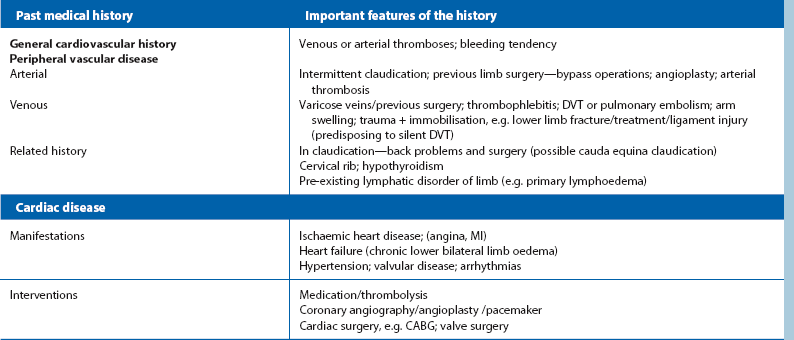

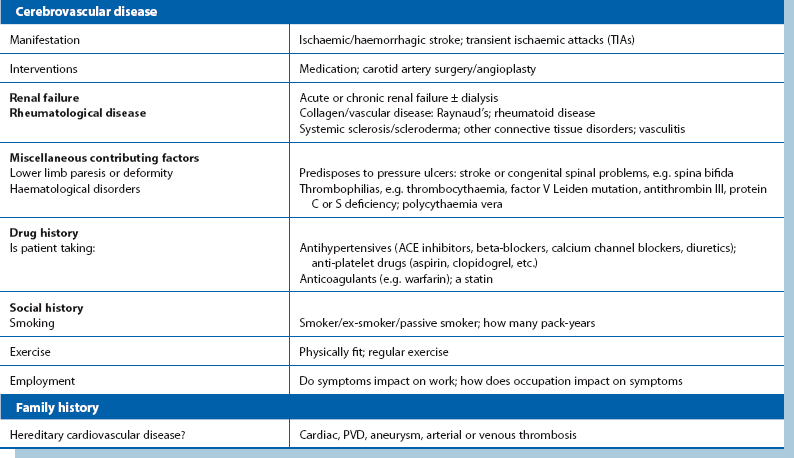

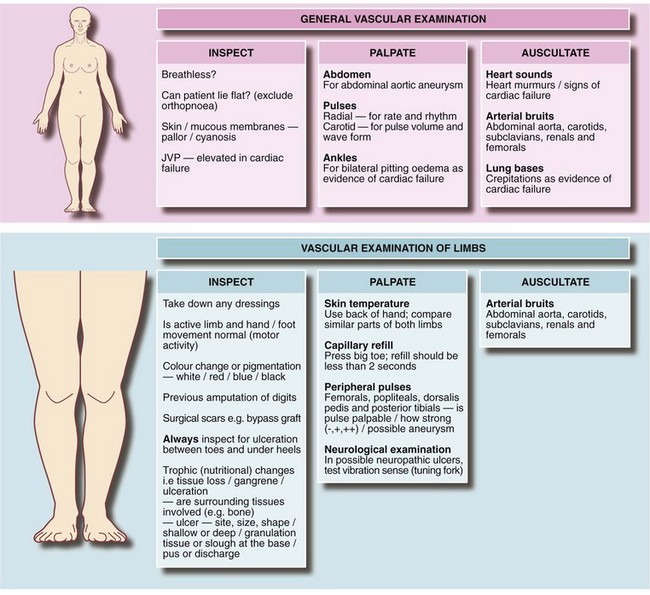

An accurate initial diagnosis depends almost entirely on skilled and methodical clinical evaluation rather than on special investigations. Preliminary assessment notes obvious major risk factors (Table 40.3). Detailed history taking is covered in Table 40.4 and examination in Figure 40.1. In a suspected vascular case, the student or doctor tries to decide if the problem is arterial, venous or lymphatic, or has some other cause.

The principal symptoms and signs of vascular disease are pain, changes in skin texture, colour and temperature, tissue loss including ulceration, and swelling. The upper limb is affected by a largely different range of disorders with signs and symptoms with only a small overlap (see Table 40.5).

Pain

Most limb pain is due to musculoskeletal disorders such as arthritis or trauma rather than vascular disease. Where lower limb peripheral ischaemia is the working diagnosis, a full cardiovascular workup is needed (see Table 40.4 and Fig. 40.1).

• Lower limb—patients may have itching and aching with varicose veins, or have exercise-related pain or severe and constant pain caused by obliterative arterial disease. Where the history is short, acute ischaemia may be the cause

• Upper limb—vascular-related pain is uncommon. Aching and swelling may be caused by subclavian vein thrombosis. Claudication is rare and acute ischaemia is usually due to embolism. Thoracic outlet syndrome is also rare. The brachial plexus may be compressed as it passes between the clavicle and first rib (or extra cervical rib) causing nerve root symptoms. Even less commonly, the condition may cause arterial or venous obstruction at the thoracic outlet

Intermittent claudication

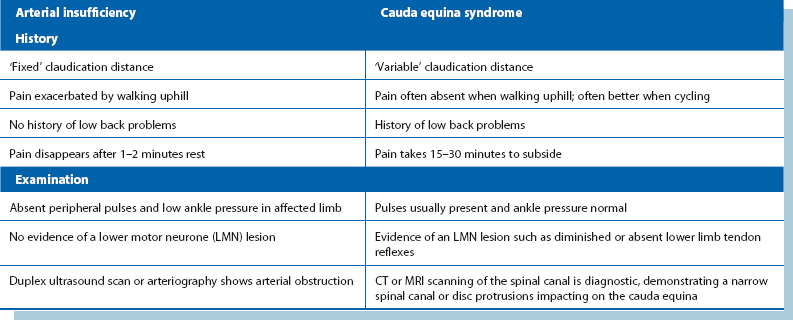

After a thorough history, only cauda equina claudication or pseudo claudication might be mistaken for ‘true’ claudication. This is caused by compression of the cauda equina in the spinal canal by central disc protrusion or canal stenosis. Lower limb pain is also brought on by exercise but there are important differences—see Table 40.6.

Acute critical ischaemia

The cardinal clinical features of acute critical ischaemia are:

• Pain—severe but variable in intensity; affects distal part of limb

• Pallor—the ischaemic area is initially white but later becomes mottled (marbling) due to stagnation of deoxygenated blood. If this blanches on pressure, the limb is still viable. If the mottling does not blanch (fixed staining) then the limb is non-viable

• Pulselessness— foot pulses are absent and popliteal and femoral pulses may be lost, depending on level of arterial occlusion

• Perishing coldness—most extreme at foot (or hand)

• Paraesthesia (reduced sensation) or anaesthesia of the periphery. This only occurs if ischaemia is severe

• Paralysis of calf muscles. The patient is unable to flex or extend toes or ankle. This only occurs if ischaemia is extreme. Pain may disappear at this stage

(As an aide-mémoire, these features are known as the six Ps: Pain, Pallor, Pulselessness, Perishing coldness, Paraesthesia, Paralysis. Not all are present all of the time; anaesthesia and paralysis are dire prognostic features and indicate that revascularisation is required immediately.)

Skin changes

In arterial insufficiency, whatever level the obstruction, the trophic effects are most evident at the periphery, i.e. the foot and toes or hand. In contrast, the changes caused by chronic venous insufficiency are most severe around the medial ankle above the malleolus (the ‘gaiter area’), almost never on the foot. Evidence of chronic venous disease includes venous eczema and haemosiderin deposition, progressing to lipodermatosclerosis (cutaneous fat around the ankle becomes thinned and indurated by fibrosis) and the characteristic ‘champagne bottle’ leg (marked sclerosis and narrowing at the ankle with oedema above—see Fig 43.1c).

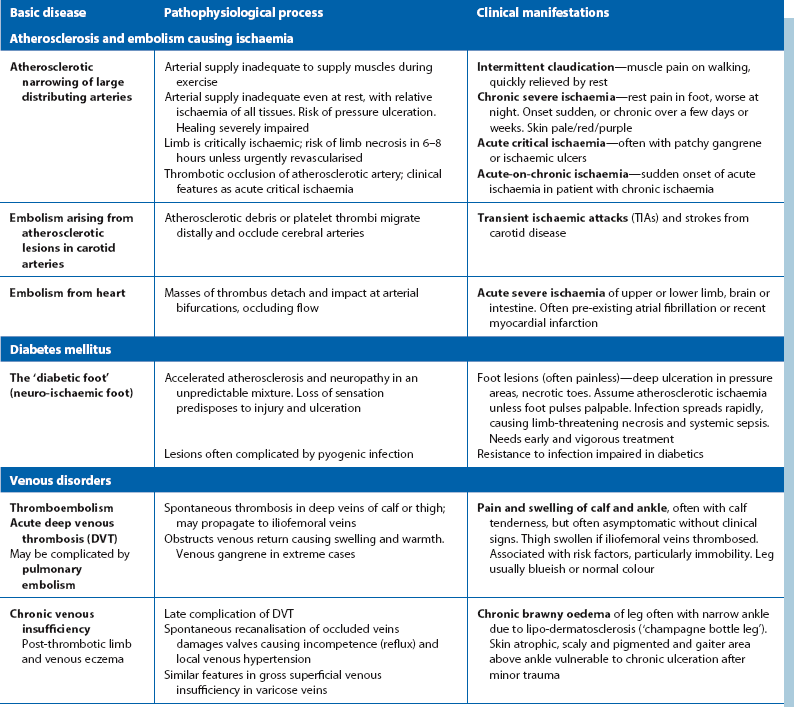

Changes in skin colour and temperature (see Table 40.7)

The acutely cold white foot: The main cause is a sudden complete arterial occlusion by thrombosis or embolism. This is usually spontaneous but precipitating events such as trauma or frostbite will be evident from the history. Ischaemia is usually unilateral unless the abdominal aorta or both iliac arteries become obstructed. Ischaemic tissue changes reach a variable distance up the leg.

Colour change in venous thrombosis: Noticeable colour change is unusual in deep venous thrombosis but massive pelvic vein thrombosis may cause changes sometimes mistaken for arterial occlusion. Massive thrombosis was once more common, especially during late pregnancy. The condition was known as white leg of pregnancy or phlegmasia alba dolens. The whole lower limb is painful, pale and massively swollen. In contrast to arterial occlusion, the limb is warm and pulses are detectable despite the oedema. A more serious variant is blue leg or phlegmasia caerulea dolens, which represents incipient venous infarction.

Blue toes: In severe claudication or rest pain, the onset of dusky skin in the foot suggests developing tissue necrosis (pre-gangrene). If finger pressure is applied to the skin, the rate of colour return gives some indication of skin perfusion (capillary refill). However, many elderly people with few symptoms have a slow refill time; these rarely have arterial disease and this can easily be excluded by Doppler ankle pressures.

Black toes: Necrosis in chronic ischaemia may be patchy and localised if there is a developed collateral circulation (Fig. 40.2). Such necrosis is usually confined to toes or part of the forefoot. The necrotic area slowly becomes hard, black and mummified (dry gangrene) and may eventually separate spontaneously from viable tissue. However, there is a risk that the necrotic area becomes infected. The tissue then becomes boggy and ulcerated and the infection and gangrene spread proximally, particularly in diabetics. This wet gangrene requires urgent treatment, often with a combination of revascularisation and amputation.

Redness: Skin redness indicates oxygenated blood is present in capillaries and implies there is no venous congestion or obstruction. With ischaemia, there is reactive dilatation of the microvasculature to hypoxia, a physiological attempt to extract the maximum oxygen from whatever blood is reaching the area. Thus severely ischaemic skin may feel cool but, paradoxically, be red—the so-called ‘sunset foot’.

Buerger’s test for severe ischaemia (Fig. 40.3) involves high elevation of the leg for a minute or two. If peripheral arterial pressure is inadequate to overcome gravity, the entire foot becomes white. When the leg is hung down, it gradually becomes blueish-red as blood flow returns. This test is easily misinterpreted—even in the normal limb, the foot will blanch somewhat with elevation.

Fig. 40.3 Buerger’s test in severe ischaemia of the lower limb

Buerger’s test is only truly positive when limbs are severely ischaemic. This 78-year-old man had severe ischaemia of both legs with the left being critically ischaemic. (a) In the first stage, one or both feet are elevated. Both feet go pale but the right is dead white. The left big toe is seen to be necrotic distally. (b) In the second stage, with dependency, both feet go blueish red, most marked on the left

The warm foot: Inflammatory dilatation of the microcirculation causes redness, and the skin is warm and slightly swollen because of enhanced blood flow. An example is low-grade bacterial cellulitis which may be seen in diabetes or chronic venous insufficiency or may arise unexpectedly. Note that if a severely ischaemic limb becomes infected, the usual signs of inflammation may not develop and the extent of infection may be underestimated. If blood supply is later restored, signs of inflammation appear.

Abnormal pigmentation: Brown pigmentation around the gaiter area is often caused by superficial or deep chronic venous insufficiency due to gross reflux in varicose veins or a post-thrombotic limb. In the latter, deep vein valves have been disrupted by inflammation, organisation and recanalisation following DVT. Valves thus become incompetent and allow deep venous reflux. This prevents an effective muscle pump and leads to chronic venous insufficiency. In gross superficial or deep venous reflux, standing causes venous stagnation, increased venous pressure in the leg (venous hypertension) and chronic leg swelling. Red cells extravasate into the tissues and form haemosiderin deposits which cause brown pigmentation. This, accompanied by dry, scaly, atrophic skin, is described as varicose or venous eczema (see Fig. 40.4).

Lower limb ulceration (Box 40.1)

• History of the origin and evolution of the ulcer

• The characteristics of the ulcer

History of the ulcer: Details of the initial skin lesion and how it occurred may provide clues. Minor trauma or an insect bite may initiate it but failure to heal can usually be attributed to abnormal skin nutrition. The common causes include chronic venous insufficiency, arterial ischaemia and diabetic neuropathy. The ulcer often begins insidiously with minor breakdown in a patch of atrophic skin. In venous insufficiency, the leg is often oedematous and the skin may ‘weep’ plasma.

The ulcer duration, its healing, and recurrences or change in extent or distribution give further clues. Ischaemic ulcers present early because pain becomes intolerable (except in diabetics with coexisting neuropathy and ischaemia)—see Table 40.8. In contrast, post-thrombotic and varicose ulcers are not severely painful and fluctuate between healing and breakdown. Very rarely, squamous carcinoma develops in a longstanding ulcer and is recognised by proliferative change at the ulcer margin. These are sometimes known as Marjolin’s ulcers and were first described following burns which failed to heal (Fig. 40.5). Primary skin malignancies on the leg may ulcerate, but these usually begin as a cutaneous lump.

Table 40.8

Main characteristics of ischaemic versus venous ulcers

| Ischaemic ulcer | Venous ulcer | |

| Pain | Yes, unless neuropathic | Minimal; not intolerable |

| Duration | Less than 6 weeks | Often months or years |

| Past history | Cardiac ischaemia/coronary artery bypass graft common | DVT; severe varicose veins |

| Limb signs | ||

| Swelling | Not swollen unless patient has been sleeping in a chair to relieve pain | Usually non-pitting plus pitting oedema unless effective bandaging in place |

| Temperature | Usually cold | Usually normal or warm |

| Pulses | Absent; low Doppler pressure | Present; normal Doppler pressure |

Fig. 40.5 Squamous carcinoma developing in a chronic venous ulcer

This very rare transformation, sometimes known as Marjolin’s ulcer, followed 34 years of continuous venous ulceration. The leg was amputated below knee and the patient cured

If the patient has claudication or rest pain, this suggests an ischaemic cause (Fig. 40.6). Neuropathic or mixed diabetic ulcers tend to be painless because of sensory neuropathy (which may be the main predisposing cause). Neuropathic changes to motor nerves affect small muscles of the foot, altering its shape and pressure areas, and autonomic dysfunction results in dryness, both predisposing to ulceration. A history or strong suspicion of previous deep venous thrombosis makes venous insufficiency the likely cause.

Site of the ulcer: Post-thrombotic and varicose ulcers typically arise just above the medial malleolus and may extend circumferentially (Fig. 40.7). They rarely occur elsewhere. Diabetic neuropathic ulcers always occur on the foot either as perforating ulcers on the sole beneath metatarsal heads or at other bony prominences; these include the toes, the ball of the great toe and the malleoli (see Fig. 41.8, p. 507), but ischaemia must always be excluded first.

Fig. 40.7 Venous (varicose) ulcer

This longstanding ulcer is typical of venous ulceration by its site, the medial gaiter area of the ankle, its relative painlessness and the presence of venous eczema surrounding it. The visible corrugations in the skin above the ulcer are caused by four-layer compression bandaging

Arterial ulcers may occur anywhere below mid-calf. Pressure ulcers occur mainly in debilitated, elderly or unconscious patients, especially at the heel (see Fig. 12.8). Even a few minutes resting on a hard casualty trolley or operating table may initiate necrosis in an ischaemic limb. Pressure ulcers usually begin as a circumscribed patch of discolouration, becoming necrotic and later ulcerating. The heels of vulnerable patients should be nursed carefully and regularly inspected to avoid this. Treatment of pressure ulcers is difficult and prolonged and it is best to prevent them.

Characteristics of the ulcer: Most ulcers are shallow, involving only skin and subcutaneous fat. Diabetic ulcers tend to penetrate deeply into the foot, where there is necrotic and infected tissue. The base of any ulcer usually contains slough and fibrin but granulation tissue may be visible beneath. Slough should not be removed unless arterial insufficiency can be excluded. If there is proliferating tissue in the ulcer, this should be biopsied.

Nature of the surrounding tissues: The surrounding tissues indicate the background on which the ulcer has formed. These include colour, e.g. chronic venous pigmentation, texture, e.g. induration, and perfusion (shown by temperature, blanching response, venous filling and Buerger’s test), as well as swelling.

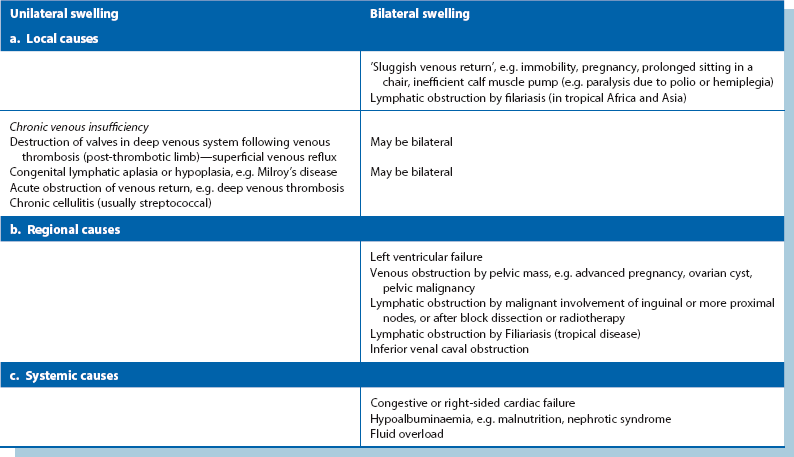

Limb swelling

Lower limb swelling may be unilateral or bilateral. The causes are summarised in Table 40.9. If bilateral, this suggests a ‘central’ cause such as heart failure. Systemic causes, and conditions listed under ‘sluggish venous return’ cause bilateral swelling. Unilateral swelling is more likely to present to a surgeon. The other causes usually produce swelling of only one limb. Most causes of unilateral swelling are chronic and painless, except for acute deep venous thrombosis and cellulitis.