Chapter 243 Parvovirus B19

Parvovirus B19 is the cause of erythema infectiosum or fifth disease.

Pathogenesis

Infections in the fetus and neonate are somewhat analogous to infections in immunocompromised persons. B19 is associated with nonimmune fetal hydrops and stillbirth in women experiencing a primary infection but does not appear to be teratogenic. Like most mammalian parvoviruses, B19 can cross the placenta and cause fetal infection during primary maternal infection. Parvovirus cytopathic effects are seen primarily in erythroblasts of the bone marrow and sites of extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver and spleen. Fetal infection can presumably occur as early as 6 wk of gestation, when erythroblasts are first found in the fetal liver; after the 4th mo of gestation, hematopoiesis switches to the bone marrow. In some cases, fetal infection leads to profound fetal anemia and subsequent high-output cardiac failure (Chapter 97). Fetal hydrops ensues and is often associated with fetal death. There may also be a direct effect of the virus on myocardial tissue that contributes to the cardiac failure. However, most infections during pregnancy result in normal deliveries at term. Some of the asymptomatic infants from these deliveries have been reported to have chronic postnatal infection with B19 that is of unknown significance.

Clinical Manifestations

Erythema Infectiosum (Fifth Disease)

The incubation period for erythema infectiosum is 4-28 days (average 16-17 days). The prodromal phase is mild and consists of low-grade fever in 15-30% of cases, headache, and symptoms of mild upper respiratory tract infection. The hallmark of erythema infectiosum is the characteristic rash, which occurs in 3 stages that are not always distinguishable. The initial stage is an erythematous facial flushing, often described as a “slapped-cheek” appearance (Fig. 243-1). The rash spreads rapidly or concurrently to the trunk and proximal extremities as a diffuse macular erythema in the 2nd stage. Central clearing of macular lesions occurs promptly, giving the rash a lacy, reticulated appearance (Fig. 243-2). The rash tends to be more prominent on extensor surfaces, sparing the palms and soles. Affected children are afebrile and do not appear ill. Some have petechiae. Older children and adults often complain of mild pruritus. The rash resolves spontaneously without desquamation but tends to wax and wane over 1-3 wk. It can recur with exposure to sunlight, heat, exercise, and stress. Lymphadenopathy and atypical papular, purpuric, vesicular rashes are also described.

Fetal Infection

Primary maternal infection is associated with nonimmune fetal hydrops and intrauterine fetal demise, with the risk for fetal loss after infection estimated at <5%. The mechanism of fetal disease appears to be a viral-induced RBC aplasia at a time when the fetal erythroid fraction is rapidly expanding, leading to profound anemia, high-output cardiac failure, and fetal hydrops. Viral DNA has been detected in infected abortuses. The second trimester seems to be the most sensitive period, but fetal losses are reported at every stage of gestation. If maternal B19 infection is suspected, fetal ultrasonography and measurement of the peak systolic flow velocity of the middle cerebral artery are sensitive, noninvasive procedures to diagnose fetal anemia and hydrops. Most infants infected in utero are born normally at term, including some who have had ultrasonographic evidence of hydrops. A small subset of infants infected in utero may acquire a chronic or persistent postnatal infection with B19 that is of unknown significance. Congenital anemia associated with intrauterine B19 infection has been reported in a few cases, sometimes following intrauterine hydrops. This process may mimic other forms of congenital hypoplastic anemia (e.g., Diamond-Blackfan syndrome). Fetal infection with B19 has not been associated with other birth defects. B19 is only one of many causes of hydrops fetalis (Chapter 97.2).

Other Cutaneous Manifestations

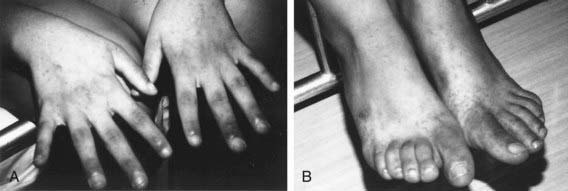

A variety of atypical skin eruptions have been reported with B19 infection. Most of these are petechial or purpuric in nature, often with evidence of vasculitis on biopsy. Among these rashes, the papular-purpuric “gloves and socks” syndrome (PPGSS) is well established in the dermatologic literature as distinctly associated with B19 infection (Fig. 243-3). PPGSS is characterized by fever, pruritus, and painful edema and erythema localized to the distal extremities in a distinct “gloves and socks” distribution, followed by acral petechiae and oral lesions. The syndrome is self-limited and resolves within a few weeks. Although PPGSS was initially described in young adults, a number of reports of the disease in children have since been published. In those cases linked to B19 infection, the eruption is accompanied by serologic evidence of acute infection.

Treatment

B19-infected fetuses with anemia and hydrops have been managed successfully with intrauterine RBC transfusions, but this procedure has significant attendant risks. Once fetal hydrops is diagnosed, regardless of the suspected cause, the mother should be referred to a fetal therapy center for further evaluation because of the high risk for serious complications (Chapter 97.2).

Douvoyiannis M, Litman N, Goldman DL. Neurologic manifestations associated with parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1713-1723.

Heegaard ED, Brown KE. Human parvovirus B19. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:485-505.

Khan J. Human bocavirus: clinical significance and implications. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:62-66.

Lindblom A, Heyman M, Gustafsson I, et al. Parvovirus B19 infection in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with cytopenia resulting in prolonged interruptions of chemotherapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:528-536.

Messina MF, Ruggeri C, Rosana M, et al. Purpuric gloves and socks syndrome caused by parvovirus B19 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:755-756.

Nigro G, Bastianon V, Colloridi V, et al. Human parvovirus B19 infection in infancy associated with acute and chronic lymphocytic myocarditis and high cytokine levels: report of 3 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:65-69.

Ramirez MM, Mastrobattista JM. Diagnosis and management of human parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Perinatol. 2005;32:697-704.

Smith SB, Libow LF, Elston DM, et al. Gloves and socks syndrome: early and late histopathologic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:749-754.

Smith-Whitley K, Zhao H, Hodinka RL, et al. Epidemiology of human parvovirus B19 in children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:422-427.

Young NS, Brown KE. Parvovirus B19. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:586-597.