Parkinson’s disease and other akinetic rigid syndromes II

There is no cure for Parkinson’s disease. The treatments available are directed at minimizing the symptoms and disabilities of the patient. Several agents have been tried to provide a neuroprotective effect and slow the deterioration of the disease, and a range of treatments such as transplantation may prove useful in the future.

The life expectancy of a patient with Parkinson’s disease is only minimally reduced.

Pharmacology

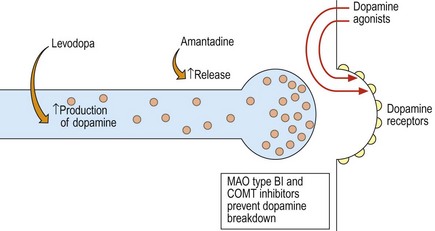

In simple terms, a reduction in dopamine and dopaminergic neurones underlies Parkinson’s disease. This dopaminergic system is antagonized by a cholinergic system. There are several levels for possible pharmacological intervention (Fig. 1; Table 1).

| Groups of drugs | Examples | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Levodopa preparations | Sinemet (levodopa plus carbidopa) | Precursor of dopamine combined with a dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor to prevent metabolism outside the brain |

| Madopar (levodopa plus benserazide) | ||

| Sinemet CR, Madopar CR | Controlled-release preparations | |

| Dopamine agonists | Bromocriptine, lisuride | Broad-spectrum dopamine agonists |

| Ergot | Pergolide | More specific agonist to D2 dopamine receptors |

| Cabergoline | ||

| Non-ergot | Apomorphine | Given subcutaneously by pump |

| Ropinirole, pramipexole | ||

| Rotigotine | Available as a patch | |

| Dopamine releasing agents, glumatergic | Amantadine | Weak symptomatic effect. May help dyskinesias |

| Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor | Selegiline, rasagiline | Mild symptomatic effect. Smoothes delivery of levodopa |

| Co-methyl-transferase inhibitors (COMT) | Entacapone | Potentially augment the effect of levodopa |

| Anticholinergics | Procyclidine | Limited efficacy |

| Benztropine | Useful for tremor. Prominent adverse effects |

Treatment

Adverse effects of dopamine agonists include nausea, dizziness, confusion, sudden bouts of sleepiness and altered behavior including gambling and hypersexuality, of which patients and their carers should be warned. Ergot-based dopamine agonists (see Table 1) may cause cardiac valvular fibrosis, and fibrosis in the lungs or abdomen. As a result, they are not routinely used and patients on these drugs require monitoring.

Complications of long-term treatment

Fluctuations

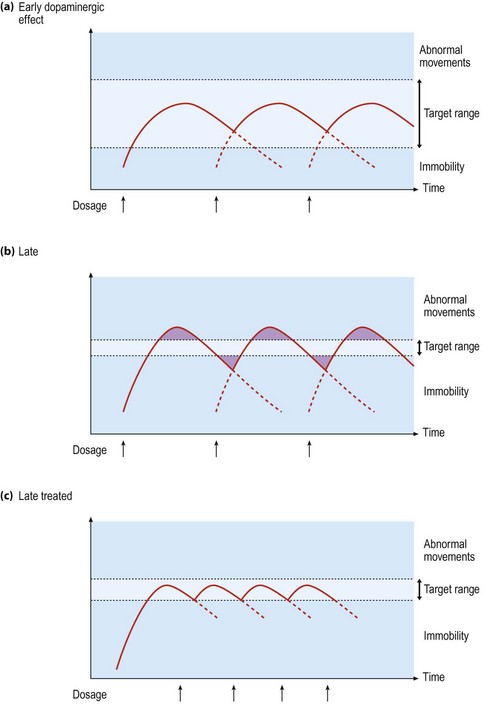

As the therapeutic window narrows, patients notice a more dramatic change in their symptoms when the drug levels are above or below a critical threshold. Initially this occurs at the end of the dose, as the drug effect wears off. This can be helped by either increasing the frequency of doses, adding selegiline or a COMT inhibitor, adding a dopamine agonist or using a controlled-release form of levodopa (Fig. 2). In some patients, the transitions seem to be more marked and random and the patient can swing violently from the rigid immobile ‘off’ state to an ‘on’ state where the patient has severe dyskinesias without any period of useful mobility. This is the ‘on-off’ effect. This is difficult to treat, but may be improved by using strategies to smooth levodopa levels (as above), by adding a dopamine agonist that has a longer half-life or by using apomorphine given subcutaneously by pump.