Chapter 391 Parenchymal Disease with Prominent Hypersensitivity, Eosinophilic Infiltration, or Toxin-Mediated Injury

391.1 Hypersensitivity to Inhaled Materials

Clinical Manifestations

Acute attacks usually occur 4-8 hr after an exposure. Symptoms include fever, chills, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, and malaise that can persist for up to 48 hr. Physical examination usually reveals an ill-appearing, dyspneic child with bibasilar crackles, wheezing, or a normal lung examination. Chest radiographs may also be normal or may demonstrate bilateral ground-glass haziness, often sparing the lung apices and bases, with fine nodulations (Fig. 391-1). These patients may progress to the subacute presentation if exposure continues or recurs. The cough worsens, dyspnea becomes more prominent, and anorexia and weight loss may occur. The chest radiograph at this stage has a more reticulonodular appearance. Long-term exposure can lead to the chronic presentation. Dyspnea and cough are severe; clubbing may be present, as are weight loss, weakness, and hypoxemia. These patients eventually develop chronic alveolitis and fibrosis that can lead to cor pulmonale. Chest radiographs show coarse reticulonodular infiltrates and bronchiectasis primarily in the upper- and mid-lung zones. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans may be more sensitive in demonstrating bronchiectasis.

Diagnosis

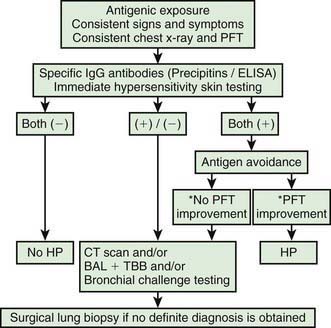

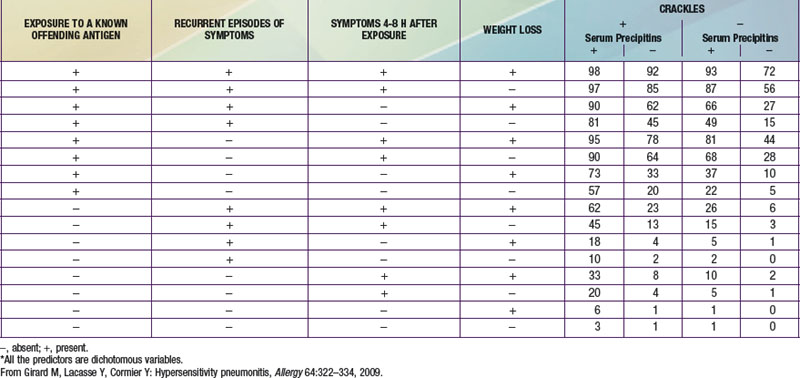

The diagnosis of HP is based primarily on the clinical presentation in association with a suspicious exposure. Because the clinical presentation is nonspecific, a high index of suspicion is crucial. Children with HP will meet most of the basic diagnostic criteria that have been proposed for adults. A variety of diagnostic criteria recommendations have been proposed. Major criteria include symptoms compatible with HP, evidence of exposure (antibody studies), compatible chest x-ray or HRCT findings, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) lymphocytosis, histologic changes compatible with HP, and a positive antigen provocation challenge. Minor criteria include bibasilar crackles, decreased diffusion capacity, and hypoxemia. The presence of 4 major and 2 minor criteria are very suggestive of HP, especially when other diseases with similar presentations have been excluded. A number of laboratory tests may also be helpful in confirming a strong clinical suspicion. HP patients often demonstrate a modest leukocytosis with neutrophilia with a left shift, and modest elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Serum levels of immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) are often elevated. Skin testing to particular antigens lacks sensitivity and specificity, as do serum precipitins to specific antigens. Both these tests may indicate exposure but are often positive in individuals without the clinical disease. In adults, BAL fluid typically demonstrates a marked lymphocytosis (often up to 70%) particularly of the CD8+ suppressor T cells, although in children the CD4 : CD8 ratio is not increased. BAL fluid may also contain higher levels of immunoglobulins. Pulmonary function tests classically demonstrate a restrictive pattern with impaired gas exchange (diffusion capacity). The presence of a mild obstructive pattern during the acute stage is a poor prognostic indicator. Some have advocated an inhalational challenge either in the laboratory or by re-exposure to the environment. Challenge testing can be dangerous and therefore should be undertaken only in appropriately equipped diagnostic centers. A diagnostic algorithm is proposed in Figure 391-2. Table 391-1 provides criteria for estimating the probability of HP; an individual living on a farm presenting with recurrent episodes of respiratory symptoms, inspiratory crackles and testing positive for the corresponding precipitating antibodies, would have an 81% chance of having HP, while an individual with progressive dyspnea and inspiratory crackles only would have a probability of HP of less than 1%.

Ceviz N, Kaynar H, Olgun H, et al. Pigeon breeder’s lung in childhood: is family screening necessary? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:279-282.

Engelhart S, Rietschel E, Exner M, et al. Childhood hypersensitivity pneumonitis associated with fungal contamination of indoor hydroponics. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009;212:18-20.

Girard M, Lacasse Y, Cormier Y. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Allergy. 2009;64:322-334.

Hanak V, Globin JM, Ryu JH. Causes and presenting features in 85 consecutive patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:812-816.

Kurup VP, Zacharisen MC, Fink JN. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:115-128.

Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Classification of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149:161-166.

Morell F, Roger A, Reyes L, et al. Bird fancier’s lung: a series of 86 patients. Medicine. 2008;87:110-130.

Natarjan A, Sutton P, Spencer DA, et al. Pigeon fancier’s lung in childhood. Respiratory Medicine Extra. 2006;2:71-73.

Stauffer Ettlin M, Pache JC, Renevey F, et al. Bird breeder’s disease: a rare diagnosis in young children. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:55-61.

Venkatesh P, Wild L. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis in children. Pediatr Drugs. 2005;7:235-244.

391.2 Silo Filler Disease

Meulenbelt J. Nitrogen and nitrogen oxides. Medicine. 2007;35:638.

Rasmussen MD, Bascom R. Silo filler’s disease. www.emedicine.com.

Tanaka N, Emoto T, Matsumoto T, et al. Inhalational lung injury due to nitrogen dioxide: high resolution computed tomography findings in 3 patients. JCAT. 2007;31:808-811.

391.3 Paraquat Lung

Afzali S, Gholyaf M. The effectiveness of combined treatment with methylprednisone and cyclophosphamide in oral paraquat poisoning. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11:387-391.

Chomchai C, Tiawilai A. Fetal poisoning after maternal paraquat ingestion during third trimester of pregnancy: case report and literature review. J Med Toxicol. 2007;3:182-186.

Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Sarmento A, Reis P, et al. Acute paraquat poisoning: report of a survival case following intake of a potential lethal dose. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:537-540.

Gil HW, Kang MS, Yang JO, et al. Association between plasma paraquat level and outcome of paraquat poisoning in 375 paraquat poisoning patients. Clinl Toxicol. 2008;46:513-518.

Hong KH, Jung JH, Eo EK. A case of moderate paraquat intoxication with pulse therapy in the subacute stage of pulmonary fibrosis. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol. 2008;6:130-133.

Lin JL, Lin-Tan DT, Chen KH, et al. Repeated pulse of methylprednisone and cyclophosphamide with continuous dexamethasone therapy for patients with severe paraquat poisoning. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:368-373.

Pinto Pereira LM, Boysielal K, Siung-Chang A. Pesticide regulation, utilization, and retailers’ selling practices in Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies: current situation and needed changes. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007;22:83-90.

Senarathna L, Eddleston M, Wilks MF, et al. Prediction of outcome after paraquat poisoning by measurement of the plasma paraquat concentration. QJM. 2009;102:251-259.

391.4 Eosinophilic Lung Disease

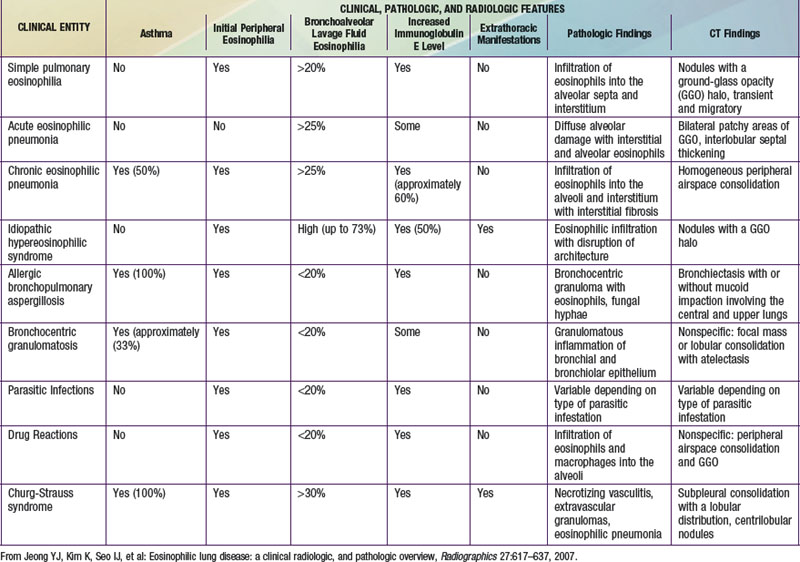

The findings of pulmonary infiltrates and circulating or tissue eosinophilia describe the heterogenous group of disorders referred to as eosinophilic lung diseases or pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia (PIE) (see Table 391-2 the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). There are numerous classification schemes for these types of lung disease. PIE syndromes can be divided into primary (idiopathic) and secondary eosinophilic lung diseases. Primary eosinophilic lung diseases include simple pulmonary eosinophilia (Löffler syndrome), acute eosinophilic pneumonia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, and idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Secondary eosinophilic lung diseases include tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, pulmonary eosinophilia with asthma, polyarteritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss syndrome, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), and drug-induced eosinophilic lung disease. Additional lung diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Langerhans cell granuloma, and other interstitial lung diseases may have associated eosinophilia but are better classified elsewhere.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

In the pediatric population, the most common etiology of PIE syndromes includes parasite infections and drug reactions. The prevalence of individual parasite infections varies geographically. The most common parasite causing PIE syndromes in the USA is Ascaris lumbricoides (Chapter 283). The eggs are ingested. After the larvae hatch, they pass through the intestinal wall and migrate to the lungs, causing an intense inflammatory reaction. Alveolar macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils are the most striking inflammatory cells. Other common parasites include Strongyloides species, Toxocara canis (dog roundworm, visceral larva migrans), and Ancylostoma braziliense (“creeping eruption”). In Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia, the filarial worms Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia malayi cause tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.

Jeong YJ, Kim K, Seo IJ, et al. Eosinophilic lung disease: a clinical radiologic, and pathologic overview. Radiographics. 2007;27:617-639.

Mann B. Eosinophilic lung disease. Clinical Medicine: Circulatory, Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine. 2008;2:99-108.

Nathan N, Guillemot N, Aubertin G, et al. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia in a 13-year-old child. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1203-1207.

Pigakis K, Meletis G, Ferdoutsis M, et al. Idiopathic eosinophilic lung diseases: a new approach to pathogenesis and treatment. Pneumon. 2008;21:156-166.

Vijayan VK. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:428-433.

Wechsler ME. Pulmonary eosinophilic syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007;27:477-492.