37 Paravertebral Block

Continuous Cervical Paravertebral Block

Perspective

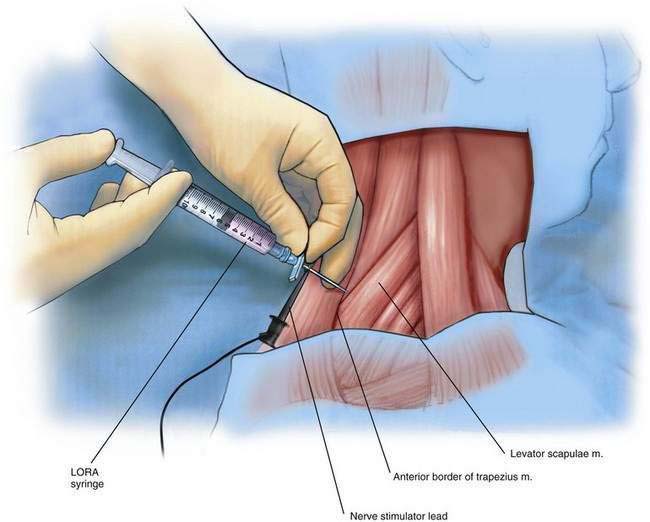

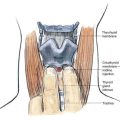

As originally described, this block was painful because it required multiple injections and penetrated the often-tender paraspinal extensor muscles of the neck. Recently, a modification was described that avoids penetration of the extensor cervical muscles. This technique minimizes the pain associated with this approach to the brachial plexus by inserting the needle in the window between the levator scapulae and trapezius muscles at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra (Fig. 37-1).

Placement

Anatomy

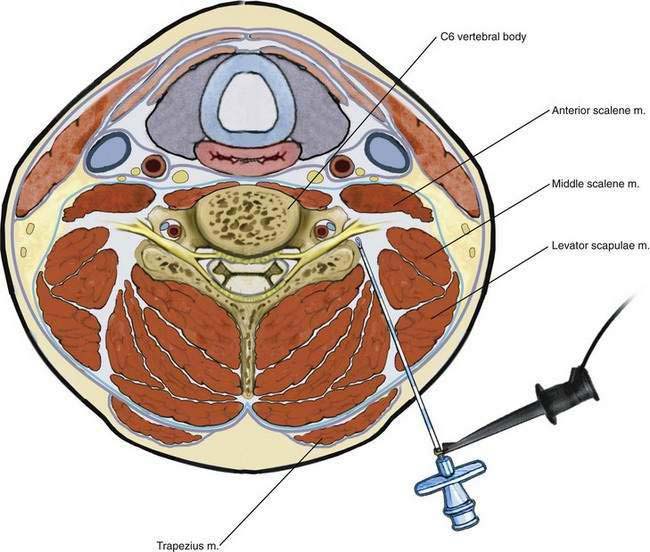

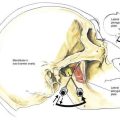

The brachial plexus is situated between the anterior and middle scalene muscles (Fig. 37-2). The phrenic nerve is anterior to the anterior scalene muscle and lateral to the superior cervical plexus. The vertebral artery and vein are situated anterior to the pars intervertebralis (articular column of the vertebrae) and typically travel through the transverse foramen in the center of the transverse processes of the first to sixth cervical vertebrae. The vertebral artery lies anterior to the interarticular parts of the vertebrae, so there is minimal risk of arterial injury with a posterior needle approach.

Needle Puncture

Next, an insulated 17- or 18-gauge Tuohy needle is inserted at the apex of the “V” formed by the trapezius and levator scapulae muscles at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra (see Fig. 37-1). The negative lead of the nerve stimulator, set to a current of 1.5 to 3 mA, a frequency of 2 Hz, and a pulse width of 100 to 300 µsec, is attached to the needle. If the block is intended for the management of pain associated with shoulder surgery, the needle is advanced anteromedially and is angled approximately 30 degrees caudad, aiming toward the suprasternal notch or cricoid cartilage until the transverse process of C6 or the pars intervertebralis of C6 is encountered. If the block is intended for wrist or elbow surgery, the needle is directed toward C7. This block is readily performed with ultrasonographic guidance, which avoids bony contact. However, close proximity to the bone is necessary if a true root-level block is intended. If the needle is directed too far laterally, the procedure will become no different from a traditional interscalene block except that the needle approach is posterior and not lateral.

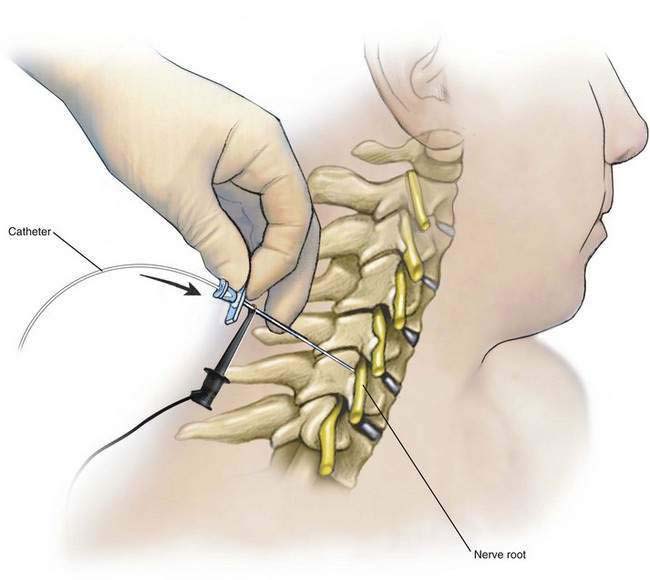

The stylet of the needle is removed after bone is encountered, and a loss-of-resistance syringe is attached to the needle. While continuously testing for loss of resistance, the needle is laterally “walked off” this bony structure and advanced anteriorly. Its course may be followed with ultrasonography, if available. Usually a distinct loss of resistance to air occurs simultaneously with a motor response observed in the biceps muscle (C5-C6) as the cervical paravertebral space is entered approximately 0.5 to 1 cm beyond the transverse process. At this level, the motor (anterior) and sensory (posterior) fibers have joined to become the roots of the brachial plexus, and more current is typically required to elicit a motor response than with an anterior interscalene technique (Fig. 37-3). If more distal surgery is planned (i.e., elbow, wrist, or hand), it is necessary to place the needle (and catheter) on the C7-C8 root, and a triceps motor response should be sought.

Catheter Placement

As the stimulating catheter is advanced, nerve stimulator output should be kept constant at a current that provides brisk muscle twitches of the shoulder or upper extremity muscles but is not uncomfortable to the patient. The catheter tip should be advanced 3 to 5 cm beyond the tip of the needle, as described in Chapter 2, Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks. After catheter advancement, the catheter is tunneled approximately 5 cm away from the insertion site to a convenient position and covered with a transparent dressing.

Thoracic Paravertebral Block: Single Injection or Continuous Infusion

Placement

Anatomy

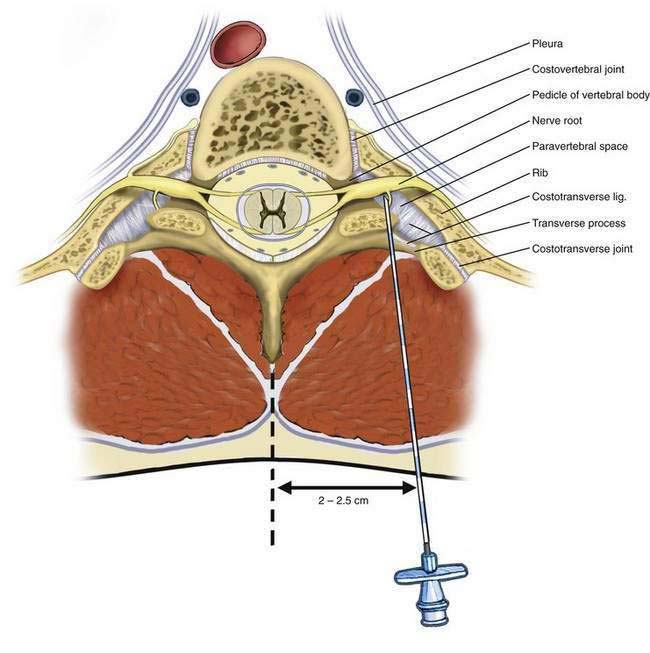

Figure 37-4 identifies the nerves in the thoracic paravertebral region that are anesthetized after injection of local anesthetic in the paravertebral space. The paravertebral space is immediately anterior to the transverse process and is bordered medially by the pedicle and vertebral body, anteriorly by the costovertebral joint, laterally by the rib and costotransverse joint, and posteriorly by the costotransverse ligament and transverse process. The endothoracic fascia bisects this space.

Needle Puncture

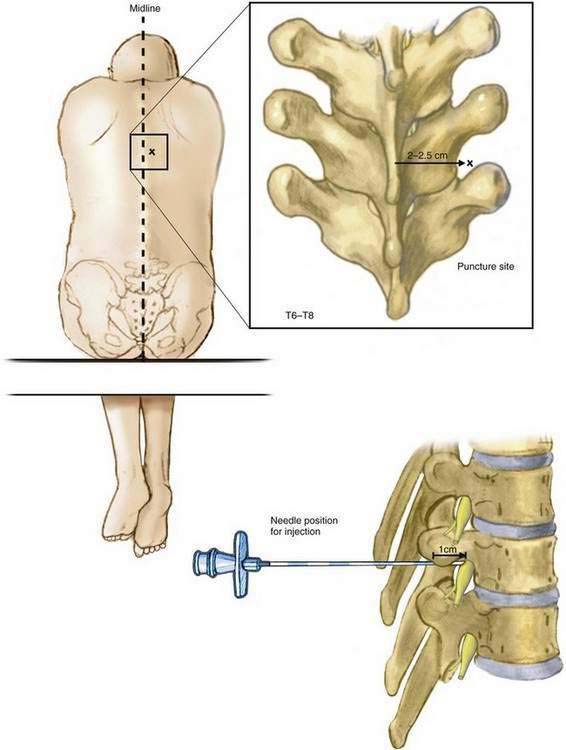

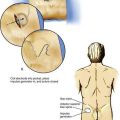

The midline of the back is identified, and the thoracic levels to be blocked are identified. A point 2 to 2.5 cm lateral to the midline and at the level of the superior border of the vertebral spinous process is marked at each level (Fig. 37-5). It is important not to choose an entry point too far lateral to minimize needle entry into the pleural cavity. The skin overlying the proposed needle insertion sites is cleaned with an appropriate disinfectant. Local anesthesia of the skin and subcutaneous tissues is produced using 1% lidocaine.

An 18-gauge Tuohy needle attached to a loss-of-resistance syringe is advanced anteriorly and slightly medially toward the transverse process. The transverse process can easily be identified on ultrasonography and the needle can be followed in-plane or out-of-plane until it contacts the transverse process, usually 3 to 5 cm from the skin in most patients. After the needle contacts the transverse process and the depth is marked, the needle should be withdrawn, redirected slightly caudad and laterally, and advanced 1 to 1.5 cm deeper than the depth at which the transverse process was encountered. Using a needle with 1-cm markings along the shaft facilitates placement, but this advancement can also be guided by ultrasonography. It is important not to advance more than 1 to 1.5 cm beyond the transverse process to limit entry into the pleural space (see Fig. 37-5). Entry of the needle into the paravertebral space should be associated with a typical loss of resistance to air (or 5% dextrose in water) as the needle penetrates the costotransverse ligament. Aspiration for air, blood, or cerebrospinal fluid should be negative, and the subsequent injection should flow easily. A total volume of 5 mL of local anesthetic is injected at each level.

Lumbar Paravertebral Block (Psoas Compartment Block): Single Injection or Continuous Infusion

Placement

Anatomy

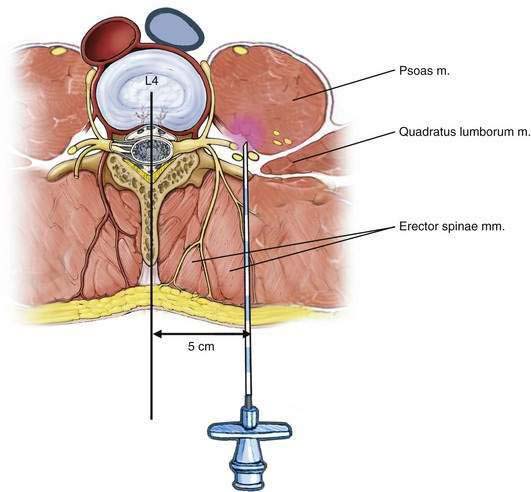

The nerves of the lumbar plexus are anesthetized by injecting a local anesthetic solution near the lumbar plexus, which is situated in the psoas compartment, anterior to the transverse process of the lumbar vertebral body (Fig. 37-6).

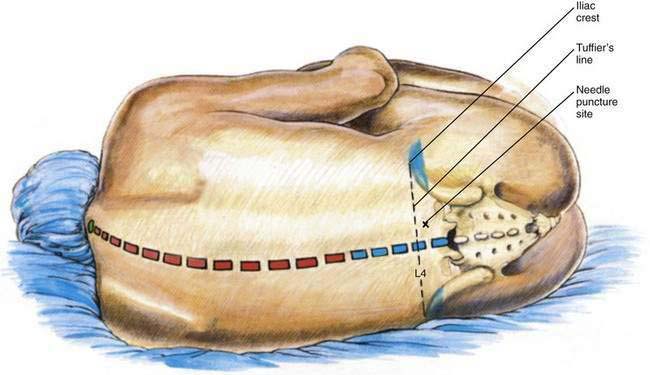

Needle Puncture

After the patient is positioned, a line is drawn between the superior margins of the iliac crests (i.e., Tuffier’s line). The vertebral spine palpable on this line in the midline is most often the fourth lumbar vertebra. The midline is marked and a second line, parallel to the midline, is drawn from the posterior superior iliac spine cephalad on the side being anesthetized. The needle insertion site is marked at a point on Tuffier’s line two thirds of the distance between the midline and the second, more laterally placed line originating from the posterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 37-7). Alternatively, the needle insertion site may be determined by identifying the L4-L5 interspace with ultrasonography. The skin overlying the proposed needle insertion site is then prepared aseptically and sterile drapes applied. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are anesthetized with 1% lidocaine.