CHAPTER 94 PARASITIC AND FUNGAL INFECTIONS

PARASITIC INFECTIONS OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

In 1909 John D. Rockefeller declared, “Deprivation in the agriculturally rich Southern States is not due to stupidity or laziness, but to parasite infestation.”1 The human immunodeficiency virus pandemic and global warming have resurrected the study of parasitology. In general, parasitic diseases are treatable and should be considered when geography, patient susceptibility, and exposure make infection possible.

More than 2 million people die each year of falciparum malaria; 200 million are infected with schistosomiasis. Toxoplasma species flourish in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Epilepsy from neurocysticercosis affects more than 1% of the population in some regions. Most cases of neurocysticercosis in Mexico remain undiagnosed despite the people having cognitive and psychiatric problems throughout life. Sleeping sickness affects 300,000 Africans and threatens many more. Intestinal helminths dull children’s minds.2

This chapter addresses the major neuroparasites, as is customary in the neurosciences, by location and clinical presentation. The aim is to present the clinician with a catalog of possibilities so that a treatable disease is not overlooked (Table 94-1).

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Amebic Encephalitis

Various features of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (a fulminant encephalitis) and granulomatous amebic encephalitis (a subacute granulomatous disease) are summarized in Table 94-2.

| Feature | PAM | GAE |

|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Swimming | Diabetes, pregnancy, alcohol/cirrhosis, corticosteroids, AIDS, chemotherapy/radiotherapy |

| Organism | Naegleria | Acanthamoeba27,28 |

| Balamuthia | ||

| Route to CNS | Olfactory epithelium/nerves | Intranasal/intracranial vasculitis leading to thrombosis and infarction |

| CNS disease | Culture-negative, fulminant, purulent meningitis; mostly PMN, unlike TB or viral | Focal or diffuse encephalitis with meningism, giant cell reaction29 |

| Organism can harbor | Yes30 | Yes |

| Legionella, Vibrio cholerae | ||

| CSF laboratory findings | Glucose variable; protein >1 g/L | Glucose variable |

| CSF microscopic findings | Motile Naegleria move 1-3 body lengths/min11 | Lymphocytic pleocytosis; trophozoite seldom found in CSF31,32 |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GAE, granulomatous amebic encephalitis; PAM, primary amebic meningoencephalitis; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; TB, tuberculosis.

Entamoeba histolytica

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by use of microscopy after staining tissue with Gomori trichrome or the iron hematoxylin method. The sensitivity of microscopy is low. The organism may not be found in stool. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (sensitivity, 87%) and polymerase chain reaction (sensitivity, 85%) are used on stool or serum.34–36

African Trypanosomiasis

Epidemiology

David Livingstone first attributed nagana to the tsetse fly (Glossina) in 1857. The disease is transmitted by male and female tsetse flies through a bite that is painful and does not go unnoticed. Trypanosoma brucei gambiense is found in West Africa; the infection takes months or years to affect the central nervous system (CNS). Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense causes an acute illness in East Africa, affecting the brain within a few months of the original bite. Transplacental transmission also occurs.

Diagnosis

T. b. rhodesiense, however, can be found in blood. Concentration techniques are used for blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples. Inoculation of rodents, which are killed after 21 days, is useful for identification of T. b. rhodesiense, but serological results are positive only after the onset of clinical symptoms, limiting its use in the asymptomatic traveler who is bitten in an endemic area where cattle are dying.37

Treatment

If CSF is positive for leukocytes and IgM concentrations are high, melarsoprol (a trivalent arsenic compound) is the drug of choice (Table 94-3). Relapse rates are high, and up to 20% of patients infected with T. b. gambiense do not respond to melarsoprol. Eflornithine is an alternative therapy for infections from T. b. gambiense but not from T. b. rhodesiense. Melarsoprol may cause post-treatment reactive encephalopathy in up to 10% of cases, with a mortality rate of 50%. Thus, the overall mortality from melarsoprol is 5% from arsenic encephalopathy.

TABLE 94-3 Treatment of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense Sleeping Sickness*

| Stage | West African (T. b. gambiense) | East African (T. b. rhodesiense) |

|---|---|---|

| Early stage | ||

| Endemic countries | According to national legislation or guidelines | According to national legislation or guidelines |

| Other countries | Pentamidine isethionate, 4 mg/kg body weight daily or on alternate days for 7 to 10 days intravenously† or intramuscularly | Suramin, test dose of 4-5 mg/kg body weight at day 1, followed by 5 injections of 20 mg/kg body weight every 7 days (e.g., days 3, 10, 17, 24, 31); the maximum dose per injection is 1 g |

| Late stage | ||

| Endemic countries | According to national legislation or guidelines | According to national legislation or guidelines |

| Other countries | If available: eflornithine, 100 mg/kg body weight at 6-hour intervals for 14 days (150 mg/kg body weight in children) by short infusions over a period of at least 30 minutes | Eflornithine not recommended (low efficacy38) |

| Alternative: melarsoprol,‡ 3 series of 3.6 mg/kg body weight at 24-hour intervals for 3 days; the series are spaced by intervals of 7 days | Melarsoprol,‡§ 1 series of 1.8, 2.16, 2.52 mg/kg body weight at 24-hour intervals; 1 series of 2.52, 2.88, 3.25 mg/kg body weight at 24-hour intervals; and 1 series of 3.6, 3.6, 3.6 mg/kg body weight at 24-hour intervals; the series are spaced by intervals of 7 days (the maximum dose is 5 mL) | |

* No firm recommendations exist for the use of the trypanocidal drugs; the schedules indicated are those most commonly used. A concise treatment schedule for treatment of T. b. gambiense sleeping sickness consisting of 10 days of melarsoprol, 2.2 mg/kg body weight daily, is under final evaluation.39,40 Note: This 10-day schedule must not be used for treatment of T. b. rhodesiense sleeping sickness, because there are no data available.

† Very slow intravenous injection or short infusion, only under well-controlled circumstances.

‡ The concomitant application of 1 mg/kg body weight prednisolone has been shown to reduce the incidence of encephalopathic syndromes in one large-scale clinical trial.41

§ A single dose of Suramin is often applied before the stage determining lumbar puncture.

From Burri C, Brun R: Human African trypanosomiasis. In Cook GC, Zumla AI, eds: Manson’s Tropical Diseases, 21st ed. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003, pp 1303-1323. Used with permission.

A lumbar puncture should be performed 1 day after a course of therapy for late-stage disease. All patients should be monitored for 2 years with lumbar punctures every 6 months. A relapse is suspected if the CSF cell count is more than 20 cells/μL. Reinfection is likely when CSF has more than 50 cells/μL, when the count has doubled since the previous count, or when there are 20 to 49 cells/μL in a symptomatic patient.25,39

Angiostrongylus cantonensis

Epidemiology

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is found mostly in southeast Asia and the Pacific Basin, but its distribution is spreading to Africa and the Caribbean. The infection is mainly acquired by eating raw or undercooked snails or slugs; it may also be acquired from eating crabs and freshwater shrimp.

Cysticercus of Taenia solium

Epidemiology

Humans are an accidental end-stage host of cysticerci, which die and degenerate in the brain, eye, and spinal cord, causing an inflammatory reaction. Cysticercosis is the most common cause of epilepsy in developing countries. T. solium intestinal carriers, releasing up to 200,000 eggs per day into their environment, are infective sources of cysticercosis, endangering all who come in contact with them. In 1993, the World Health Organization declared cysticercosis a potentially eradicable disease by tracing human carriers of T. solium. In the early 19th century, cysticercosis was diagnosed in 2% of autopsies in Berlin, roughly the same rate as found today in Mexico.11 The Commission on Tropical Diseases of the International League Against Epilepsy states that the prevalence of active epilepsy in tropical countries ranges from 1% to 1.5%, almost twice the level in Western countries. Regions and peoples with a religious aversion to pork are spared.24,43,44

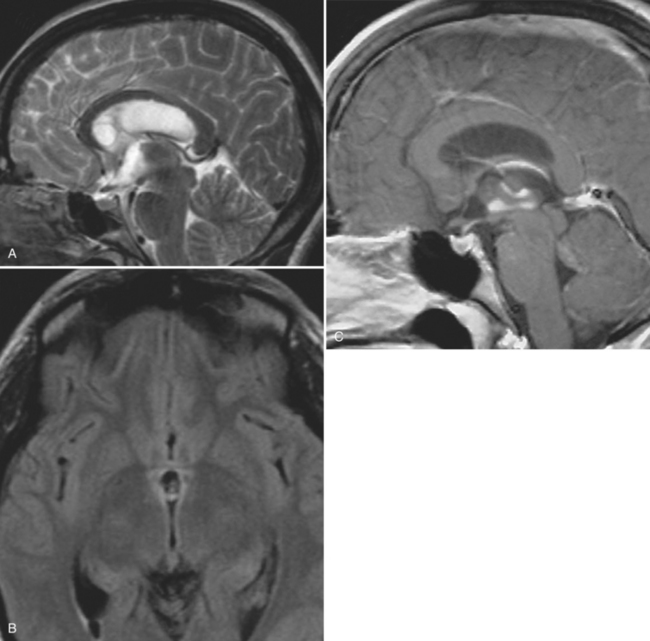

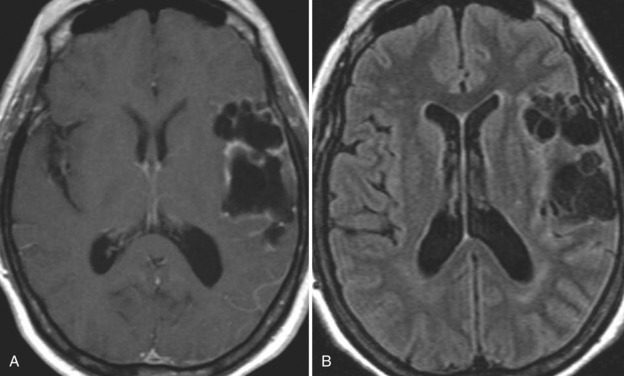

Clinical Presentation

With parenchymal disease, most children (80%) present with seizures. Episodic headaches and vomiting are featured in one third. Ventricular cysts may wander in the isodense CSF and cause hydrocephalus through an intermittent ball-valve effect. Subarachnoid cysts can result in meningeal signs, usually without fever. Rarely, cysticerci erode into large vessels. Arachnoiditis is another cause of hydrocephalus, as well as focal vasculitis, which may be responsible for lacunar strokes. Small space-occupying lesions are responsible for focal weakness. Cognitive and psychiatric impairments are common. In the eye, a scotoma may develop or vision may be lost.45

Diagnosis

Blood and CSF serological analyses have improved. Many clinicians use the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB) assay. It derives from coproantigens of adult T. solium and ignores nonspecific bands of antigen. EITB results may revert to negative after the cysticercus dies. The assay is not always readily available. In the blood, sensitivity is 92.5% and specificity is 100%. However, EITB sensitivity has been reported to be as low as 28% in subjects with a single parenchymal lesion, as is commonly seen in India.46 EITB sensitivity may be less in CSF.47

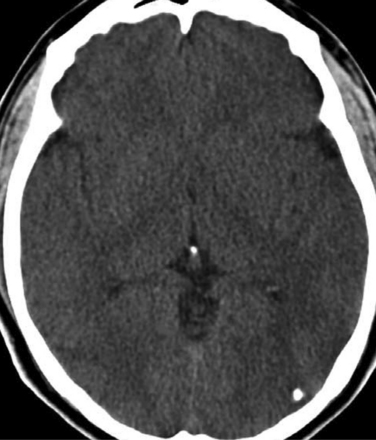

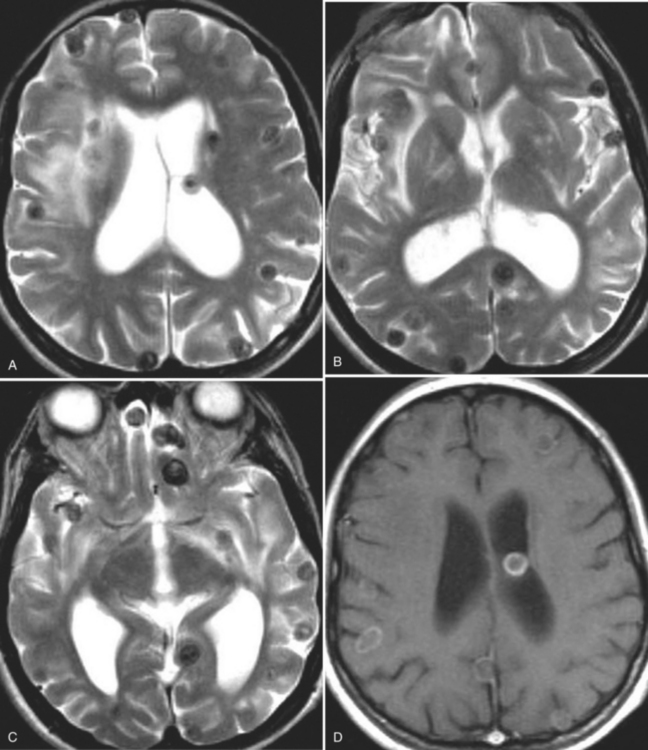

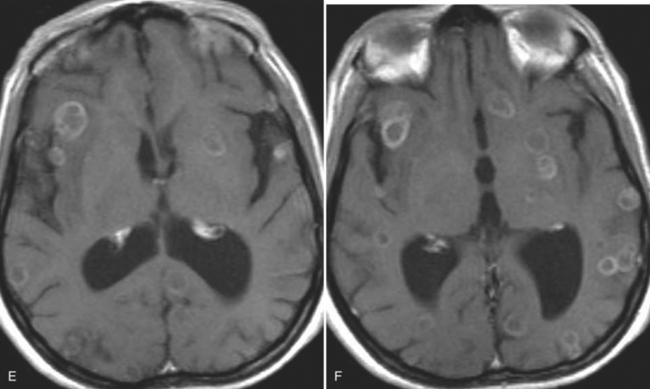

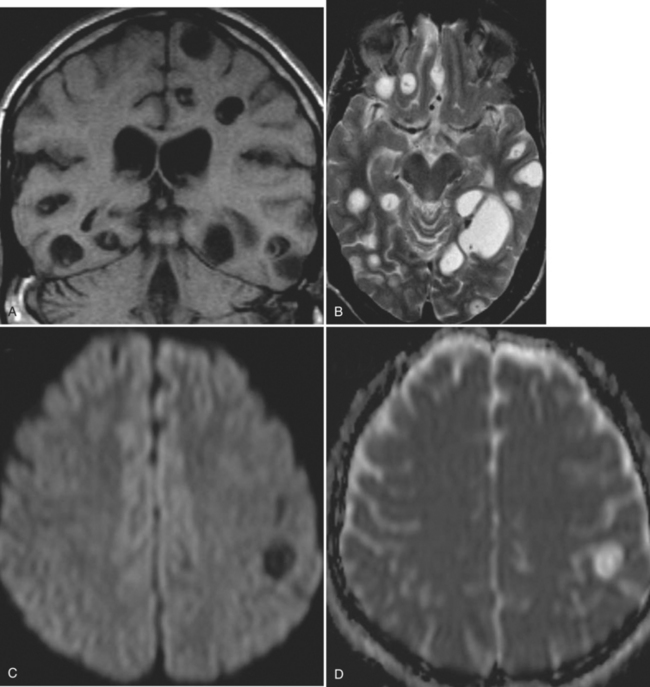

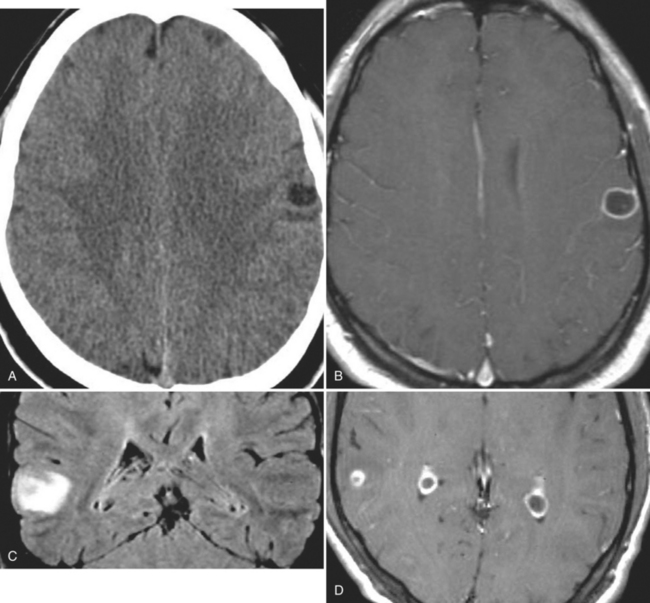

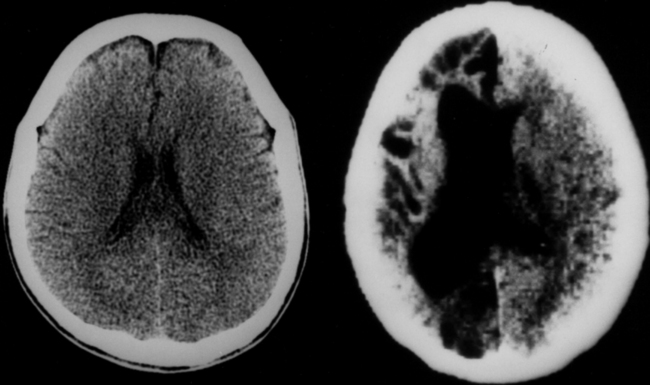

The diagnosis requires neuroimaging, with the goal of identifying the scolex (2 to 3 mm). Only since the frequent use of computed tomography in the 1980s has cysticercosis emerged as the most common cause of epilepsy in many areas. (Cerebral malaria is likely the most common cause of febrile seizures.) Magnetic resonance imaging may show a diagnostic invaginated scolex but not show the calcific stage, for which computed tomography is best. Magnetic resonance imaging can show ventricular cysts. In brain parenchyma, the cysts mature in 3 months to 10mm in size (occasionally up to 20mm); in the ventricles, they can exceed 5 cm. Therefore, serum EITB, CSF ELISA, and neuroimaging have become useful diagnostic tools48,49 (Figs. 94-1 through 94-7).

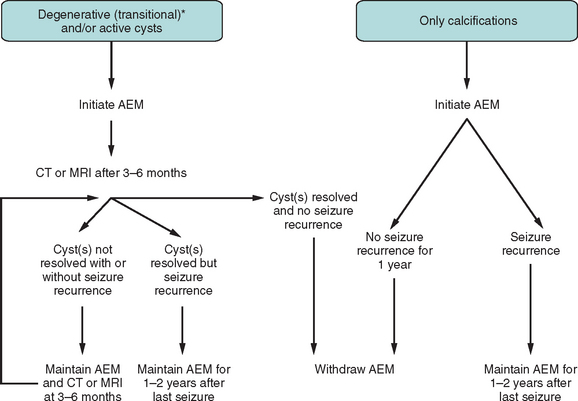

Treatment

In the tropics, studies have shown that hypoproteinemia, malabsorption, and malnutrition affect drug kinetics. This has been shown with chloroquine, phenylbutazone, chloramphenicol, carbamazepine, and others. Higher doses of antiepileptics are sometimes required (Fig. 94-8).

In the tropics, studies have shown that hypoproteinemia, malabsorption, and malnutrition affect drug kinetics. This has been shown with chloroquine, phenylbutazone, chloramphenicol, carbamazepine, and others. Higher doses of antiepileptics are sometimes required (Fig. 94-8). Corticosteroids are indicated for cerebral edema and focal inflammation around a dead or dying cyst. They are used along with a cysticidal drug for multiple parenchymal brain cysts, giant (>5 cm) subarachnoid cysts, ventricular cysts, and spinal cysts. For arachnoiditis, the duration of corticosteroid therapy can be determined by repeat CSF examination.53,54

Corticosteroids are indicated for cerebral edema and focal inflammation around a dead or dying cyst. They are used along with a cysticidal drug for multiple parenchymal brain cysts, giant (>5 cm) subarachnoid cysts, ventricular cysts, and spinal cysts. For arachnoiditis, the duration of corticosteroid therapy can be determined by repeat CSF examination.53,54 Subarachnoid cysticercosis generally requires antiparasitic therapy. The dose and duration of therapy are controversial, and multiple courses of treatment may be required. An ophthalmological examination should precede the use of antiparasitic medication. Cysticercocidal drugs may cause irreparable damage, and when considering larvacidal medication, each case must be studied individually. Albendazole (15 mg/kg per day) may be given orally for 7 or more days. Simultaneously, dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg per day) may be given. Enhancing lesions will degenerate regardless of therapy, but larvicidal medication may increase resolution and reduce recurrence of seizures.55,56

Subarachnoid cysticercosis generally requires antiparasitic therapy. The dose and duration of therapy are controversial, and multiple courses of treatment may be required. An ophthalmological examination should precede the use of antiparasitic medication. Cysticercocidal drugs may cause irreparable damage, and when considering larvacidal medication, each case must be studied individually. Albendazole (15 mg/kg per day) may be given orally for 7 or more days. Simultaneously, dexamethasone (0.1 mg/kg per day) may be given. Enhancing lesions will degenerate regardless of therapy, but larvicidal medication may increase resolution and reduce recurrence of seizures.55,56 Surgical excision is considered for extraparenchymal (ventricular and subarachnoid) cysts. CSF diversion is usually required for hydrocephalus.57,58

Surgical excision is considered for extraparenchymal (ventricular and subarachnoid) cysts. CSF diversion is usually required for hydrocephalus.57,58

Figure 94-8 Antiepileptic treatment for patients with first seizure due to neurocysticercosis.52 Asterisk indicates that “degenerative” includes a single enhancing lesion on computed tomography (computed tomography) after differential diagnosis has been established. AEM, antiepileptic medication; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

(From Carpio A: Neurocysticercosis: an update. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2:751-762. Used with permission.)

Falciparum Malaria

Pathophysiology

Cytoadherence and sequestration clog cerebral vessels with parasitized red blood cells, which adhere to endothelial receptors. Ligands for adhesion are produced by the parasite and are expressed on knobs on the red blood cell surface. Cytokine excess in the capillaries, where sequestration occurs, appears to be more significant than obstruction of flow. To avoid passage through the spleen, which would eliminate the parasites, they travel inside red blood cells and adhere to endothelial cells and other red blood cells in the brain, lung, liver, placenta, and other organs. Massive infection may occur with low peripheral parasitemia.62,63

Cytoadherence and sequestration clog cerebral vessels with parasitized red blood cells, which adhere to endothelial receptors. Ligands for adhesion are produced by the parasite and are expressed on knobs on the red blood cell surface. Cytokine excess in the capillaries, where sequestration occurs, appears to be more significant than obstruction of flow. To avoid passage through the spleen, which would eliminate the parasites, they travel inside red blood cells and adhere to endothelial cells and other red blood cells in the brain, lung, liver, placenta, and other organs. Massive infection may occur with low peripheral parasitemia.62,63 Capillary permeability, including breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, leads to perivascular edema. Pulmonary edema occurs in adults and is less common in children.64–67

Capillary permeability, including breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, leads to perivascular edema. Pulmonary edema occurs in adults and is less common in children.64–67Clinical Presentation

Severe falciparum malaria is clearly defined and should be treated parenterally initially (Table 94-5). Patients with cerebral malaria present with coma, convulsions, dysconjugate gaze, pouting, and bruxism. Retinal hemorrhages are seen. CNS findings are symmetrical. The plantar reflexes are upgoing.68

|

Cerebral malaria, defined as unrousable coma (lasting >1 hour after a seizure) not attributable to any other cause in a patient with falciparum malaria

|

Modified from the World Health Organization: Management of Severe Malaria: A Practical Handbook, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000, p 5. Used with permission.

In children with febrile convulsions followed by coma, 30 to 60 minutes may have to pass before malaria is diagnosed, but treatment should not be delayed. Patients with malarial convulsions may present with only nystagmus, salivation, and twitching of the mouth or a digit. One third of seizures in children manifest only as eye deviation or salivation, or both. One in 10 children with severe malaria has sequelae: ataxia, hemiparesis (hemiconvulsion-hemiparesis syndrome), speech disorder, blindness, behavioral problems, cognitive difficulties (executive functions), and spasticity. Prolonged seizures, coma, hypoglycemia, and absence of hyperpyrexia are associated with neurological sequelae.69

Treatment

Common errors in treating malaria are the following:

Treatment guidelines with quinine and quinidine for severe malaria are as follows:

Quinine dihydrochloride (salt), 20 mg/kg, is given as an intravenous (IV) load over 4 hours, in 5 to 10 mL/kg of 5% dextrose in saline; 8 to 12 hours after the start of the load, 10 mg/kg (salt) is given at the same dilution, over 4 hours, and repeated every 8 to 12 hours until oral medication is taken, for a total of 7 days.

Quinine dihydrochloride (salt), 20 mg/kg, is given as an intravenous (IV) load over 4 hours, in 5 to 10 mL/kg of 5% dextrose in saline; 8 to 12 hours after the start of the load, 10 mg/kg (salt) is given at the same dilution, over 4 hours, and repeated every 8 to 12 hours until oral medication is taken, for a total of 7 days. Quinidine (base), 15 mg/kg, equivalent to 20 mg/kg of quinidine gluconate, is given as an IV load over 4 hours; then 7.5 mg/kg (base), equivalent to 10 mg/kg of IV quinidine gluconate, is given over 1 to 2 hours, every 8 hours until oral medication is taken, for a total of 7 days.

Quinidine (base), 15 mg/kg, equivalent to 20 mg/kg of quinidine gluconate, is given as an IV load over 4 hours; then 7.5 mg/kg (base), equivalent to 10 mg/kg of IV quinidine gluconate, is given over 1 to 2 hours, every 8 hours until oral medication is taken, for a total of 7 days. Because quinidine, the dextrorotatory isomer of quinine, is more effective and more cardiotoxic than quinine, the patient must be monitored electrocardiographically: the QRS complex should not exceed a 50% increase over the pretreatment complex and the QTc interval should not show more than a 25% increase. The IV dose may be reduced by one third after 48 hours.

Because quinidine, the dextrorotatory isomer of quinine, is more effective and more cardiotoxic than quinine, the patient must be monitored electrocardiographically: the QRS complex should not exceed a 50% increase over the pretreatment complex and the QTc interval should not show more than a 25% increase. The IV dose may be reduced by one third after 48 hours. Side effects of quinine include cinchonism, hypoglycemia, and a prolonged QT interval. A loading dose should be avoided if quinine, quinidine, or mefloquine were taken within 24 hours.

Side effects of quinine include cinchonism, hypoglycemia, and a prolonged QT interval. A loading dose should be avoided if quinine, quinidine, or mefloquine were taken within 24 hours. Doxycycline is added to quinine, quinidine, or mefloquine as 2.5 mg/kg daily (100 mg every 12 hours) for 7 days; if the patient is younger than 8 years or pregnant, use clindamycin instead.

Doxycycline is added to quinine, quinidine, or mefloquine as 2.5 mg/kg daily (100 mg every 12 hours) for 7 days; if the patient is younger than 8 years or pregnant, use clindamycin instead.The artemisinins clear parasitemia faster than quinine:

Artesunate (2.4 mg/kg) is given as an IV or intramuscular (IM) load, followed by 1.2 mg/kg daily for a minimum of 3 days or until the patient can swallow quinine or mefloquine and doxycycline for a total of 7 days.

Artesunate (2.4 mg/kg) is given as an IV or intramuscular (IM) load, followed by 1.2 mg/kg daily for a minimum of 3 days or until the patient can swallow quinine or mefloquine and doxycycline for a total of 7 days. Artemether (3.2 mg/kg) is given as an IM load, followed by 1.6 mg/kg repeated every 12 to 24 hours for a minimum of 3 days or until the patient can swallow quinine or mefloquine and doxycycline for a total of 7 days. Artemether is formulated in peanut oil for injection.

Artemether (3.2 mg/kg) is given as an IM load, followed by 1.6 mg/kg repeated every 12 to 24 hours for a minimum of 3 days or until the patient can swallow quinine or mefloquine and doxycycline for a total of 7 days. Artemether is formulated in peanut oil for injection.Corticosteroids are associated with an increased risk of adverse side effects and do not decrease mortality. The diagnosis and management of severe malaria70 and therapeutic options are discussed in other publications.25,70–76

Gnathostoma spinigerum

Epidemiology

Gnathostoma spinigerum, a nematode larva, is acquired in Southeast Asia, Japan, and Latin America from eating undercooked fish, frogs, snakes, ducks, and chicken. Ceviche and sushi are known sources of infection.

Clinical Presentation

One to 2 days after the larva is ingested, it causes epigastric pain as it penetrates the gastric mucosa. A retrospective study of 946 cases of gnathostomiasis in Mexico City identified nodular migratory panniculitis over the trunk as the most common skin sign.77 Migrating immature worms move through spinal foramina at all levels, causing sudden, severe radicular pain and nerve palsy. This resolves in a few days as the worm races to the brain, causing symptoms for as long as 15 years. Focal symptoms are present as well as eosinophilic meningitis with myeloencephalitis, and 25% of the CNS cases are fatal.

Diagnosis

Eosinophilia is prominent and serum levels of IgE are elevated. Diagnosis is by serology (ELISA when available: sensitivity, 93%; specificity, 96.7%) and magnetic resonance imaging (cervical cord enlargement and hemorrhagic tracts in the brain with scattered deep intracerebral hemorrhages). Microscopic examination is diagnostic.78

Paragonimus

Clinical Presentation

The lung infection can be mistaken for bronchiectasis. It may be misdiagnosed as nocardiosis, tuberculosis, or metastatic lung cancer. Symptoms may be recognized for years before diagnosis.79 Epilepsy occurs in 65% to 95% of CNS cases before diagnosis. Chronic mild insidious eosinophilic meningitis (the majority of cases), or recurrent acute meningitis, as well as chronic decline in mental status persisting for as long as 20 years is described. Homonymous hemianopia is common.80,81 Flukes in the spinal cord cause spastic paraplegia.82

Diagnosis

Chest radiographic abnormalities are seen in 80% of patients. Oh83 reviewed 62 cases of cerebral paragonimiasis and found CSF eosinophilia in 8% and peripheral eosinophilia in 41%. If available, serology by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and complement fixation on CSF samples may be used for diagnosis and for monitoring therapy. Microscopic examination is performed on stool, gastric washings, sputum, or tissue.84

In chronic brain syndrome, magnetic resonance imaging shows multiple conglomerated, round, enhancing nodules (“soap bubbles”) with encephalomalacia in the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. Computed tomography scans show large calcified nodules or multiple cystic calcifications in the same region in 40% to 70% of cases.20,80,82,83

Schistosoma japonicum

Diagnosis

Stool microscopy is performed. Immunodiagnosis is similar to that of S. mansoni. On magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, there may be focal and asymmetrical findings, such as a dilated ventricle from massive egg embolization. CSF opening pressure is increased. The CSF cell count is increased (5 to 55 monocytes per high-power field), with increased protein and normal glucose concentrations. Partial seizures are more common in the Philippines and China, whereas generalized seizures are more common in Japan85 (Fig. 94-9).

Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium

Epidemiology

Schistosomiasis affects 200 million people in the Middle East, Africa, Brazil, Suriname, Venezuela, and the Caribbean, wherever the freshwater snail vector is found. In CNS disease, S. haematobium can be found in the brain, but S. mansoni and S. haematobium are more commonly found in the spinal cord.

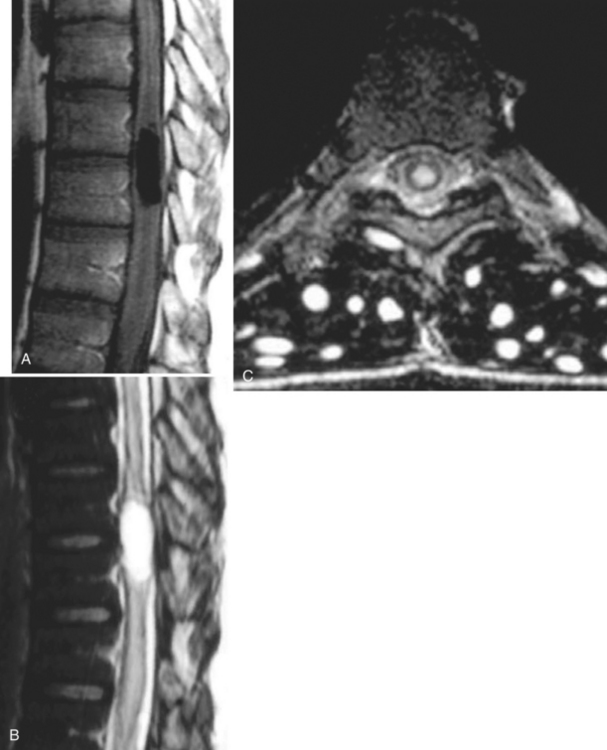

Clinical Presentation

S. mansoni is the most common cause of schistosomal myeloradiculopathy. The second most common is S. haematobium. Radicular symptoms may occur at any stage of the infection but are more likely during early stages, or with mild chronic forms, than during later stages with severe forms of the disease, such as the hepatosplenic stage.86 In Brazil, Nascimento-Carvalho and Moreno-Carvalho87 reported that the most common CNS manifestations in pediatric neuroschistosomiasis due to S. mansoni are paraparesis (55%), urinary retention (53%), and paraplegia (20%).

Diagnosis

CSF eosinophilia with increased concentrations of protein is common. Stool and urine microscopy and rectal biopsy are diagnostic (S. haematobium eggs are easily detected in the urine). S. mansoni is sometimes found in the urine. Multiple techniques allow schistosome antigens to be identified in the serum, urine, and CSF, mostly using ELISA and circulating anodic antigen. An ELISA of the CSF is helpful for suspected CNS infection.88 Magnetic resonance imaging shows an enlarged spinal cord.

Toxoplasma gondii

Epidemiology

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan found worldwide from Alaska to Australia. One third of the human population has been exposed. In one third of AIDS patients who are Toxoplasma seropositive, cerebral toxoplasmosis reactivates. Toxoplasmosis sickens fetuses and immunosuppressed hosts. Prophylactic medication has impacted the prevalence of postnatal infection. Nonfetal infection is acquired by ingesting tissue cysts in undercooked meat (pork, lamb, and rabbit) or oocysts in cat feces that have contaminated food, water, or hands (pregnant women should wear gloves when gardening). In British Columbia, a water reservoir became infected from use by cougars. Toxoplasmosis may be transmitted by blood transfusion and organ donation. Immunosuppressive therapy prescribed to transplant patients puts them at higher risk.89

Pathophysiology

CD4 and CD8 cells and possibly astrocytes prevent reactivation in immune individuals. CD4 counts less than 100/μL are associated with more severe infections. TH1 helper T cells produce interleukin 2, interferon γ, and tumor necrosis factors α and β. Interferon γ has a preeminent role in the development of toxoplasmosis. Its synthesis results in chronic asymptomatic infection. When the CD4 cell count is less than 100/μL, interferon γ production decreases or stops. The imbalance between TH1 and TH2 responses allows interleukins 4 and 10 to further downregulate the secretion and activity of interferon γ. With progression of disease, multifocal necrotizing encephalitis develops, particularly in the thalamus, basal ganglia, and the intersection between white and gray matter in the frontal and temporal cortex.90

In dormant stages, bradyzoites are within pseudocysts in brain tissue and skeletal muscle. With reactivation, tachyzoites invade virtually any cell. The parasite favors neurons over microglial cells because they do not express major histocompatibility complex class 1 molecules and cannot be eliminated by sensitized CD8+ T cells.65

Clinical Presentation

Acute toxoplasmosis induces a mononucleosis-like illness. Acute infection or reactivation in the immunosuppressed patient may result in encephalitis and devastating disease. Severe bilateral headache has little response to analgesics. Focal neurological signs are common (69% of cases). Seizures are observed in 15% to 30% as a presenting sign. Depression, bipolar disorder, altered mental status, ataxia, and dementia may follow. Blindness, with mental retardation and intracranial calcification (Table 94-6), and hydrocephalus occur in neonates.

TABLE 94-6 Infectious Causes of Central Nervous System Calcifications

FUNGAL INFECTIONS OF THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Central Nervous System Cryptococcosis

C. neoformans is a round or oval yeast that has a worldwide distribution and is found particularly in bird excreta.91 Infection is acquired through inhalation of the organism. Most pulmonary infections are asymptomatic, but acute symptomatic pneumonia may occur. Infection can disseminate to distant sites either during this primary lung infection or later during reactivation, usually as a result of cell-mediated immune deficiency.92 The most likely site for dissemination is the CNS, but the reason is not entirely clear. Some investigators have hypothesized that there is a receptor in the CNS that binds a ligand on the organism, but this hypothesis has not been verified.

Patients with CNS cryptococcosis usually present with a subacute meningitis, with signs and symptoms such as headache, fever, and focal neurological deficits occurring over several weeks.93,94 Symptoms may be subtle, waxing and waning. Classic meningeal symptoms (e.g., neck stiffness or photophobia) may not always be present. In particular, in human immunodeficiency virus infection, they are present in only one fourth to one third of patients. Brain imaging studies are also nonspecific; computed tomography scans may be normal in one half the cases. Cerebral atrophy and ventricular enlargement are the most common findings in human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients. Cryptococcomas (nodules in the brain parenchyma) can also be present occasionally, especially in patients with infection caused by C. neoformans var. gattii. CSF findings usually include an increased opening pressure, mild mononuclear pleocytosis, and increased protein concentration. India ink examination of the CSF is positive in 50% of non-AIDS patients with cryptococcal meningitis and in more than 80% of patients with AIDS. Similarly, cultures of CSF are usually positive. Both the serum and the CSF cryptococcal antigen tests are accurate for the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis, with sensitivity and specificity greater than 90%.

The recommended treatment of cryptococcal meningitis has three stages, particularly in patients with HIV infection:95,96

Chronic suppression can be discontinued if patients remain asymptomatic and have a sustained increase in CD4 counts of more than 100 to 200/μL for at least 6 months after antiretroviral therapy.95

Patients without HIV infection either follow the same treatment algorithm as for HIV patients or are treated with a 6- to 10-week regimen of amphotericin B, with or without initial flucytosine.94 If the 6- to 10-week regimen is selected, the decision to discontinue treatment will depend on resolution of symptoms, negative CSF cultures on at least two occasions, and normal CSF values. Patients with ongoing immunosuppression that may have initially predisposed them to cryptococcal infection will require an additional 6 to 12 months of fluconazole therapy after these criteria are met. Increased intracranial pressure is a common feature of cryptococcal meningitis, particularly in patients with AIDS.97 It may result in a delayed clinical response and death; therefore, decompression may be required through drainage of the CSF by either serial lumbar punctures or placement of a shunt.

Central Nervous System Histoplasmosis

H. capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus, which means that it occurs as a mold (mycelial form) in nature and as a yeast in tissue (and at temperatures less than 37°C in cultures).98 The yeast form is a small, thin-walled, oval structure measuring 2 to 4mm in diameter. H. capsulatum is found in temperate zones around the world. In the United States, it is endemic in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.99 Its natural habitat is soil, especially soil with high organic content such as soil enriched with bird, chicken, or bat excrement.

Infection is acquired by inhalation and deposition of mycelial fragments into the alveoli. The organism converts to its pathogenic yeast form and is phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. Specific T cell–mediated immunity develops and inhibits the growth of the organisms. However, the persistence of the organisms within granulomas can lead to reactivation or dissemination (or both) of the disease during the immunosuppressed state.100

CNS involvement occurs either as an isolated infection or as part of a progressive disseminated disease.101,102 In disseminated disease, CNS involvement is noted in 5% to 10% of cases. Clinical presentation varies widely and includes meningitis, diffuse encephalitis, focal neurological deficits, and stroke syndromes. Unless the yeast is identified in different organs, the diagnosis of CNS infection itself may be problematic.101–103 CSF findings are nonspecific, usually with lymphocytic pleocytosis, decreased glucose levels, and increased protein levels. CSF cultures are often negative early in the disease, and they require multiple specimens, large volumes (greater than 10 mL), and an extended incubation period (longer than 35 days). Serological tests for anti-Histoplasma antibodies in the CSF may be positive in up to 80% of cases. Testing for Histoplasma polysaccharide antigen in the CSF can be useful in 38% to 67% of cases.104

The treatment of choice for CNS histoplasmosis is amphotericin B, 0.7 to 1 mg/kg per day for a total dose of 30 to 35 mg/kg, followed by fluconazole, 800 mg daily for 9 to 12 months.96,105 Itraconazole does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier well and therefore should not be used. Criteria for discontinuing treatment include a normal concentration of CSF glucose and an undetectable level of CSF Histoplasma polysaccharide antigen. If immunodeficiency cannot be reversed, lifelong maintenance therapy may be required. Some clinicians prefer lipid formulations of amphotericin B because they deliver higher doses with less toxicity. If lipid formulations are used, they should be administered at dosages of 3 to 5 mg/kg per day for a total of 100 to 150 mg/kg over 6 to 12 weeks.

Central Nervous System Blastomycosis

B. dermatitidis is also a dimorphic fungus.98 The yeast cells are round and thick walled with daughter cells forming from a broad-based bud. It is an endemic fungus found primarily in the south central, southeastern, and midwestern United States, especially in the states along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, as well as in the Canadian provinces bordering the Great Lakes.106 Occasionally, cases have also been reported in Africa, India, the Middle East, Central America, and South America. Outdoor activities near waterways and exposure to dust from construction and excavation sites are the major risk factors for acquiring infection.

Infection begins with inhalation of the organism, which then enters the lungs and converts to its yeast phase. Infection at this stage is usually asymptomatic. Cellular immunity is the major host protective factor in preventing progression of disease. Symptomatic disease develops in about one half of infected individuals. In some, the infection spreads via the bloodstream and lymphatics to distant sites, most commonly skin, bone, and the genitourinary system.107

CNS involvement is uncommon (less than 5%) in immune-competent patients with blastomycosis.108,109 In contrast, as many as 40% of AIDS patients with blastomycosis have been reported to have CNS disease, usually as a fulminant complication of widely disseminated blastomycosis.110 CNS blastomycosis manifests itself as either an abscess or meningitis. Both are difficult to diagnose in the absence of a diagnosis from another site in the body. CSF cultures are rarely positive, and culture of ventricular fluid may have a higher yield. Biopsy of cranial abscesses may be required for identification of the organism.

For patients with CNS blastomycosis, amphotericin B deoxycholate remains the drug of choice.111 A total dose of at least 2g is usually recommended. For patients unable to tolerate a full course of amphotericin B, fluconazole at a dosage of 800 mg/day can be substituted. Human immunodeficiency virus–infected or otherwise significantly immunocompromised patients with CNS blastomycosis require long-term suppressive therapy with fluconazole.96

Central Nervous System Coccidioidomycosis

C. immitis is a dimorphic fungus endemic to certain areas in the southwestern United States and parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America.112 The yeast form has a unique spherical structure known as a spherule, which is a large, round, thick-walled structure filled with daughter cells or endospores. As a spherule matures, its outer wall becomes thinner and eventually ruptures. This results in the release of endospores, which may propagate further in tissue.

Infection is acquired by inhalation of the organism and the subsequent formation of a lung lesion is the consequence of an inflammatory response. Many of the infections are either asymptomatic or mild and self-limited.113 As with the other endemic fungi, control of the infection is dependent on cell-mediated immunity.

Coccidioidomycosis rarely spreads beyond the lungs. However, immunodeficiency conditions, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection, immunosuppressive therapy, Hodgkin lymphoma, and transplant recipients, dramatically increase the risk of dissemination.114,115 Other conditions that increase the likelihood of dissemination include pregnancy and African or Filipino ancestry. Up to one third of disseminated cases present with meningitis. Infection predominantly affects the basilar meninges. However, intracerebral abscesses occasionally develop.116,117 The most common symptoms are headache, nausea, vomiting, and altered mental status. Hydrocephalus is a common complication of coccidioidal meningitis.

CSF analysis shows mononuclear pleocytosis with decreased glucose and increased protein concentrations. CSF eosinophilia occurs in up to 70% of cases. Serological testing plays a more important role in the diagnosis and management of coccidioidomycosis than of other fungal infections.118 Tube precipitin-reacting antibodies disappear and are not found in chronic infections, whereas complement-fixing antibodies are present as long as infection persists; they disappear when the infection resolves. Complement-fixing antibodies can also be detected in the CSF of patients with meningitis and similarly can be useful for monitoring disease. Culture of the CSF is often negative.

The standard treatment for coccidioidal meningitis had been intrathecal amphotericin B, but this treatment is now reserved for patients who do not respond to oral azole therapy. The current preferred initial treatment for coccidioidal meningitis is oral fluconazole at 400 mg/day.119 Some patients may need higher doses of fluconazole. Treatment should be continued for at least 1 year and for 6 months after all evidence of further improvement has ceased. Relapses occur in approximately one third of patients when therapy is stopped, and some patients may require suppressive therapy indefinitely. In addition to antifungal therapy, a shunting procedure may be required to control hydrocephalus. If present, abscesses may require drainage or resection.

Central Nervous System Mucormycosis

The term mucormycosis describes a group of diseases caused by fungi that belong to the order Mucorales.120 The genera reported to cause invasive infection include Rhizopus, Absidia, Cunninghamella, Rhizomucor, Mucor, Apophysomyces, Saksenaea, Cokeromyces, and Syncephalastrum. These organisms are morphologically filamentous with broad, nonseptate hyphae with branches occurring at right angles. They are ubiquitous in nature and are common inhabitants of decaying matter and soil.

The most common clinical presentation of mucormycosis is rhinocerebral mucormycosis.121,122 As the name implies, infection starts in the nose and paranasal sinuses and spreads to the orbit and the adjacent structures of the brain, commonly the frontal lobe and the cavernous sinus. The clinical manifestations of rhinocerebral mucormycosis reflect the involvement of the tissues and structures. Initial complaints are facial pain and headache. Fever may not be present. With further progression of the infection, additional complaints and findings include erythema and ulceration of the palate, periorbital cellulitis, proptosis, swelling of the conjunctiva, cranial nerve dysfunction, loss of vision, mental status changes, and coma.

Isolated CNS mucormycosis has also been reported. The majority of these reports were in intravenous drug users.123 The most common clinical presentation includes mental status changes and focal neurological deficits. The infection appears to have a predilection for basal ganglia.

Treatment of mucormycosis needs to be prompt and aggressive. Both surgical débridement of necrotic tissue and antifungal therapy are required. Repeated débridement is often necessary. The agents of mucormycosis are relatively refractory to antifungal therapy. They require high doses of amphotericin B deoxycholate, typically 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg per day. Lipid preparations of amphotericin B are acceptable alternatives and may permit the delivery of high doses of amphotericin B with less toxicity. None of the currently available azoles or echinocandins are active against the organisms that cause mucormycosis. However, posaconazole, a new azole that is currently in phase III trials and is also available in compassionate use protocols, has been reported to have good activity against some of the agents that cause mucormycosis.124,125 The overall mortality rate of mucormycosis is approximately 50%.

Central Nervous System Aspergillosis

Aspergillus is a mold that is ubiquitous in the environment worldwide, being found primarily in decaying vegetation but also in soil and water. Its hyphae (filaments) are thin and septated, branching off at acute angles. The most common species causing invasive infection include Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, and Aspergillus niger.126 Infection is usually acquired by inhalation into the lungs. In persons without effective host defenses (e.g., neutropenic patients, patients receiving corticosteroid treatment, and transplant recipients), the inhaled organisms enlarge and germinate, invade tissue, and eventually cause disseminated infection. Tissue and vascular invasiveness is the hallmark of Aspergillus infections.127

The most common clinical manifestation of Aspergillus infection is invasive pulmonary infection. CNS aspergillosis may occur in up to 10% to 20% of all cases of invasive aspergillosis. Reports suggest that it is being encountered more frequently than in the past. Although it usually occurs as part of a disseminated infection with concomitant pulmonary infection, isolated CNS aspergillosis has been reported, particularly in intravenous drug users. Even though it has been reported among patients with HIV infection, CNS aspergillosis does not appear to be more common in HIV patients than in other immunocompromised patients. Its most common manifestation is a brain abscess causing headache, focal neurological signs, and altered mental status. The spectrum of CNS disease includes meningitis, hemorrhages, bland infarctions, myelitis, epidural abscesses, and mycotic aneurysms.128–134

The diagnosis of CNS aspergillosis requires the demonstration of the organism and its invasion in CNS tissue or isolation of the organism from a biopsy specimen or CSF. Blood cultures are rarely positive. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain most commonly shows single or multiple ring-enhancing lesions with surrounding edema. Other radiographic appearances include hemorrhagic infarction pattern, parenchymal hemorrhage pattern, and diffuse necrotic encephalitis pattern.135 An enzyme immunoassay for detecting Aspergillus galactomannan, an Aspergillus antigen, has been licensed in the United States for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis.136 Although not extensively evaluated, at least one report suggests that detection of Aspergillus galactomannan in CSF may be of diagnostic value.137

Historically, invasive aspergillosis as a whole is refractory to treatment, with overall mortality rates of 50% or more. CNS aspergillosis carries the poorest prognosis, with mortality rates of more than 90% reported in most series.138 The following antifungal agents are active against Aspergillus species: amphotericin B deoxycholate, lipid forms of amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, and caspofungin. Voriconazole is considered by many as the agent of first choice for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis. This may also apply for the treatment of CNS aspergillosis. New drugs in development, such as posaconazole, ravuconazole, micafungin, and anidulafungin are also active against Aspergillus species and may offer new options for therapy. All drugs need to be given at high doses, and the optimal duration of therapy is unknown. Although it would be reasonable to continue to treat until clinical and radiographic abnormalities have resolved, it may be necessary to continue treatment as long as the underlying predisposition for invasive Aspergillus infection exists. Stereotactic drainage of abscesses may be required.139

Benson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, et al. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:S131-S235.

CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases. Parasitic disease information. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/listing.htm.

Cook GC, Zumla AI, editors. Manson’s Tropical Diseases. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003.

Cortez KJ, Walsh TJ. Space-occupying fungal lesions. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the Central Nervous System. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:713-734.

Drugs for parasitic infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. Available at http://www.medletter.com/freedocs/parasitic.pdf, 2004.

Garcia HH, Del Brutto OH, Nash TE, et al. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis (Taenia solium). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:3-9.

Perfect JR. Fungal meningitis. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the Central Nervous System. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:691-712.

Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the central nervous system, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Sobel JD, Mycoses Study Group. Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America: practice guidelines for the treatment of fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:652.

Walker M, Zunt JR. Parasitic central nervous system infections in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1005-1015.

1 Nevins A. Study In Power: John D. Rockefeller, Industrialist and Philanthropist. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953.

2 Awasthi S, Bundy DA, Savioli L. Helminthic infections. BMJ. 2003;327:431-433.

3 Ing MB, Schantz PM, Turner JA. Human coneurosis in North America: case reports and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:519-523.

4 Ferreira MS, Nishioka Sde A, Silvestre MT, et al. Reactivation of Chagas’ disease in patients with AIDS: report of three new cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1397-1400.

5 Breniere SF, Bosseno MF, Noireau F, et al. Integrate study of a Bolivian population infected by Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:289-295.

6 Pinto NX, Torres-Hillera MA, Mendoza E, et al. Immune response, nitric oxide, autonomic dysfunction and stroke: a puzzling linkage on Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Med Hypotheses. 2002;58:374-377.

7 da Cunha AB. Chagas’ disease and the involvement of the autonomic nervous system. Rev Port Cardiol. 2003;22:813-824.

8 Di Lorenzo GA, Pagano MA, Taratuto AL, et al. Chagasic granulomatous encephalitis in immunosuppressed patients: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Neuroimaging. 1996;6:94-97.

9 Suiter TM, Schreiner-Suiter S, Glockner WM. Cerebral immune vasculitis as a complication of larva migrans infection caused by Toxocara canis [in German]. Med Klin (Munich). 1993;88:445-448.

10 Osoegawa M. Diagnosis and treatment of central nervous system parasite infection with special reference to parasitic myelitis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2004;44:961-964.

11 Cook GC, Zumla AI, editors. Manson’s Tropical Diseases. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2003.

12 Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the Central Nervous System, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

13 Hashim FA, Ahmed AE, el Hassan M, et al. Neurologic changes in visceral leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:149-154.

14 Jin E, Ma D, Liang Y, et al. MRI findings of eosinophilic myelomeningoencephalitis due to Angiostrongylus cantonensis.. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:242-250.

15 Gupta S, Desai K, Goel A. Intracranial hydatid cyst: a report of five cases and review of literature. Neurol India. 1999;47:214-217.

16 Altinors N, Bavbek M, Caner HH, et al. Central nervous system hydatidosis in Turkey: a cooperative study and literature survey analysis of 458 cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:1-8.

17 Tüzün M, Altinörs N, Arda IS, et al. Cerebral hydatid disease computed tomography and MR findings. Clin Imaging. 2002;26:353-357.

18 Sawanyawisuth K, Tiamkao S, Kanpittaya J, et al. MR imaging findings in cerebrospinal gnathostomiasis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:446-449.

19 Choo JD, Suh BS, Lee HS, et al. Chronic cerebral paragonimiasis combined with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:466-469.

20 Kaw GJ, Sitoh YY. Clinics in diagnostic imaging (58): chronic cerebral paragonimiasis. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:89-91.

21 Mao SC, Ye XC, Liu JX, et al. CT brain scanning in the diagnosis and localisation of cerebral schistosomiasis [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 1989;7:115-118.

22 Kirchhoff LV, Nash TE. A case of schistosomiasis japonica: resolution of CAT-scan detected cerebral abnormalities without specific therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:1155-1158.

23 Putman CE, Ravin CE, editors. Textbook of Diagnostic Imaging, 2nd ed., Vols 1, 2. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994.

24 Commission on Tropical Diseases of the International League Against Epilepsy. Relationship between epilepsy and tropical diseases. Epilepsia. 1994;35:89-93.

25 Drugs for parasitic infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. Available at http://www.medletter.com/freedocs/parasitic.pdf, 2004.

26 CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases. Parasitic disease information. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/listing.htm.

27 Storey MV, Winiecka-Krusnell J, Ashbolt NJ, et al. The efficacy of heat and chlorine treatment against thermotolerant Acanthamoebae and Legionellae. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:656-662.

28 Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. Acanthamoeba spp. as agents of disease in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:273-307.

29 Velho V, Sharma GK, Palande DA. Cerebrospinal acanthamebic granulomas: case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:572-574.

30 Kilvington S, Price J. Survival of Legionella pneumophila within cysts of Acanthamoeba polyphaga following chlorine exposure. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;68:519-525.

31 Alizadeh H, Apte S, El-Agha MS, et al. Tear IgA and serum IgG antibodies against Acanthamoeba in patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 2001;20:622-627.

32 Bloch KC, Schuster FL. Inability to make a premortem diagnosis of Acanthamoeba species infection in a patient with fatal granulomatous amebic encephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3003-3006.

33 Stanley SLJr. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025-1034.

34 Haque R, Ali IK, Akther S, et al. Comparison of PCR, isoenzyme analysis, and antigen detection for diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:449-452.

35 Furrows SJ, Moody AH, Chiodini PL. Comparison of PCR and antigen detection methods for diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica infection.. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1264-1266.

36 Delialioglu N, Aslan G, Sozen M, et al. Detection of Entamoeba histolytica/Entamoeba dispar in stool specimens by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:769-772.

37 Truc P, Lejon V, Magnus E, et al. Evaluation of the micro-CATT, CATT/Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, and LATEX/T b gambiense methods for serodiagnosis and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis in west and central Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:882-886.

38 Iten M, Mett H, Evans A, et al. Alterations in ornithine decarboxylase characteristics account for tolerance of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense to D, L-α-difluoromethylornithine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1922-1925.

39 Burri C, Nkunku S, Merolle A, et al. Efficacy of new, concise schedule for melarsoprol in treatment of sleeping sickness caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1419-1425.

40 Schmid C, Nkunku S, Merolle A, et al. Efficacy of 10-day melarsoprol schedule 2 years after treatment for late-stage gambiense sleeping sickness. Lancet. 2004;364:789-790.

41 Pepin J, Milord F. The treatment of human African trypanosomiasis. Adv Parasitol. 1994;33:1-47.

42 Slom TJ, Cortese MM, Gerber SI, et al. An outbreak of eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in travelers returning from the Caribbean. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:668-675.

43 Roman G, Sotelo J, Del Brutto O, et al. A proposal to declare neurocysticercosis an international reportable disease. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:399-406.

44 Mitchell WG. Neurocysticercosis and acquired cerebral toxoplasmosis in children. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1999;6:267-277.

45 Hawk MW, Shahlaie K, Kim KD, et al. Neurocysticercosis: a review. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:123-132.

46 Narula G, Bawa KS. Neurocysticercosis: new millennium, ancient disease and unending debate. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:337-342.

47 Wilson M, Bryan RT, Fried JA, et al. Clinical evaluation of the cysticercosis enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot in patients with neurocysticercosis. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:1007-1009.

48 Villota GE, Gomez DI, Volcy M, et al. Similar diagnostic performance for neurocysticercosis of three glycoprotein preparations from Taenia solium metacestodes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:276-280.

49 Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White ACJr, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 2001;57:177-183.

50 Rajshekhar V, Jeyaseelan L. Seizure outcome in patients with a solitary cerebral cysticercus granuloma. Neurology. 2004;62:2236-2240.

51 Singh G, Kaushal S, Gupta M, et al. Cutaneous reactions in patients with solitary cysticercus granuloma on phenytoin sodium. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:331-333.

52 Carpio A, Hauser WA. Neurocysticercosis and epilepsy. In: Singh G, Prabhakar S, editors. Taenia solium Cysticercosis: From Basic to Clinical Science. Chandigarh, India: CABI Publishing; 2002:211-220.

53 Garcia HH, Pretell EJ, Gilman RH, et al. A trial of antiparasitic treatment to reduce the rate of seizures due to cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:249-258.

54 Singhi P, Jain V, Khandelwal N. Corticosteroids versus albendazole for treatment of single small enhancing computed tomographic lesions in children with neurocysticercosis. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:323-327.

55 Kalra V, Dua T, Kumar V. Efficacy of albendazole and shortcourse dexamethasone treatment in children with 1 or 2 ring-enhancing lesions of neurocysticercosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2003;143:111-114.

56 Garcia HH, Evans CA, Nash TE, et al. Current consensus guidelines for treatment of neurocysticercosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:747-756.

57 Psarros TG, Zouros A, Coimbra C. Neurocysticercosis: a neurosurgical perspective. South Med J. 2003;96:1019-1022.

58 Garcia HH, Del Brutto OH, Nash TE, et al. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis (Taenia solium). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:3-9.

59 Carpio A. Neurocysticercosis: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:751-762.

60 Garcia HH, Del Brutto OH. Taenia solium cysticercosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:97-119.

61 White ACJr. Neurocysticercosis: updates on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:187-206.

62 Adams S, Brown H, Turner G. Breaking down the blood-brain barrier: signaling a path to cerebral malaria? Trends Parasitol. 2002;18:360-366.

63 de Souza JB, Riley EM. Cerebral malaria: the contribution of studies in animal models to our understanding of immunopathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:291-300.

64 Mhlanga JD, Bentivoglio M, Kristensson K. Neurobiology of cerebral malaria and African sleeping sickness. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:579-589.

65 Kristensson K, Mhlanga JD, Bentivoglio M. Parasites and the brain: neuroinvasion, immunopathogenesis and neuronal dysfunctions. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;265:227-257.

66 Wassmer SC, Combes V, Grau GE. Pathophysiology of cerebral malaria: role of host cells in the modulation of cytoadhesion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;992:30-38.

67 Baruch DI, Pasloske BL, Singh HB, et al. Cloning the P. falciparum gene encoding PfEMP1, a malarial variant antigen and adherence receptor on the surface of parasitized human erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:77-87.

68 Beare NA, Southern C, Chalira C, et al. Prognostic significance and course of retinopathy in children with severe malaria. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1141-1147.

69 Holding PA, Stevenson J, Peshu N, et al. Cognitive sequelae of severe malaria with impaired consciousness. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:529-534.

70 World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malaria: A Practical Handbook. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Available at http://www.who.int/malaria/docs/hbsm.pdf.

71 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for treatment of malaria in the United States (based on drugs currently available for use in the United States). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/pdf/treatmenttable.pdf, 2004.

72 The Roll Back Malaria Partnership: RBM: a global partnership. Available at http://www.rbm.who.int/, 2005.

73 Ogutu BR, Newton CR. Management of seizures in children with falciparum malaria. Trop Doct. 2004;34:71-75.

74 Mturi N, Musumba CO, Wamola BM, et al. Cerebral malaria: optimising management. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:153-165.

75 Artemether-Quinine Metaanalysis Study Group. A metaanalysis using individual patient data of trials comparing artemether with quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:637-650.

76 Newton CR, Hien TT, White N. Cerebral malaria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:433-441.

77 Magana M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

78 Diaz Camacho SP, Zazueta Ramos M, Ponce Torrecillas E, et al. Clinical manifestations and immunodiagnosis of gnathostomiasis in Culiacan, Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:908-915.

79 Miyazaki I. Cerebral paragonimiasis. Contemp Neurol Ser. 1975;12:109-132.

80 Kim SK. Cerebral paragonimiasis: a report of forty-seven cases. Arch Neurol. 1959;1:30-37.

81 Joo EY, Kim JH, Tae WS, et al. Simple partial status epilepticus localized by single-photon emission computed tomography subtraction in chronic cerebral paragonimiasis. J Neuroimaging. 2004;14:365-368.

82 Kusner DJ, King CH. Cerebral paragonimiasis. Semin Neurol. 1993;13:201-208.

83 Oh SJ. Cerebral paragonimiasis. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1967;92:275-277.

84 Maleewong W. Recent advances in diagnosis of paragonimiasis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28(Suppl 1):134-138.

85 Hayashi M. Clinical features of cerebral schistosomiasis, especially in cerebral and hepatosplenomegalic type. Parasitol Int. 2003;52:375-383.

86 Ferrari TC, Moreira PR, Cunha AS. Spinal-cord involvement in the hepatosplenic form of Schistosoma mansoni infection. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:633-635.

87 Nascimento-Carvalho CM, Moreno-Carvalho OA. Clinical and cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients less than 20 years old with a presumptive diagnosis of neuroschistosomiasis. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50:98-100.

88 Mansour MM, Ali PO, Farid Z, et al. Serological differentiation of acute and chronic schistosomiasis mansoni by antibody responses to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;41:338-344.

89 Hill D, Dubey JP. Toxoplasma gondii: transmission, diagnosis and prevention. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:634-640.

90 Sarciron ME, Gherardi A. Cytokines involved in toxoplasmic encephalitis. Scand J Immunol. 2000;52:534-543.

91 Levitz SM. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1163-1169.

92 Perfect JR, Casadevall A. Cryptococcosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:837-874.

93 Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Cloud GA, et al. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients in the era of effective azole therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:690-699.

94 Powderly WG. Cryptococcal meningitis and AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:837-842.

95 Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:710-718.

96 Benson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, et al. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(Suppl 3):S131-S235.

97 Graybill JR, Sobel J, Saag M, et al. The NIAID Mycoses Study Group and AIDS Cooperative Treatment Groups. Diagnosis and management of increased intracranial pressure in patients with AIDS and cryptococcal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:47-54.

98 Maresca B, Kobayashi GS. Dimorphism in Histoplasma capsulatum and Blastomyces dermatitidis.. Contrib Microbiol. 2000;5:201-216.

99 Ajello L. Distribution of Histoplasma capsulatum in the United States. In: Ajello L, Chick EW, Furcolow ML, editors. Histoplasmosis. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1971:103-122.

100 Wheat LJ, Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:1-19.

101 Wheat LJ, Batteiger BE, Sathapatayavongs B. Histoplasma capsulatum infections of the central nervous system: a clinical review. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69:244-260.

102 Wheat LJ, Connolly-Stringfield PA, Baker RL, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment, and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69:361-374.

103 Joseph Wheat L. Current diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:488-494.

104 Wheat LJ, Garringer T, Brizendine E, et al. Diagnosis of histoplasmosis by antigen detection based upon experience at the histoplasmosis reference laboratory. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;43:29-37.

105 Wheat J, Sarosi G, McKinsey D, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:688-695.

106 Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

107 Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40.

108 Kravitz GR, Davies SF, Eckman MR, et al. Chronic blastomycotic meningitis. Am J Med. 1981;71:501-505.

109 Gonyea EF. The spectrum of primary blastomycotic meningitis: a review of central nervous system blastomycosis. Ann Neurol. 1978;3:26-39.

110 Pappas PG, Pottage JC, Powderly WG, et al. Blastomycosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:847-853.

111 Chapman SW, Bradsher RWJr, Campbell GDJr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:679-683.

112 Pappagianis D. Epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1988;2:199-238.

113 Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1077-1082.

114 Deresinski SC, Stevens DA. Coccidioidomycosis in compromised hosts: experience at Stanford University Hospital. Medicine (Baltimore). 1975;54:377-395.

115 Logan JL, Blair JE, Galgiani JN. Coccidioidomycosis complicating solid organ transplantation. Semin Respir Infect. 2001;16:251-256.

116 Mischel PS, Vinters HV. Coccidioidomycosis of the central nervous system: neuropathological and vasculopathic manifestations and clinical correlates. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:400-405.

117 Banuelos AF, Williams PL, Johnson RH, et al. Central nervous system abscesses due to Coccidioides species. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:240-250.

118 Pappagianis D, Zimmer BL. Serology of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:247-268.

119 Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Catanzaro A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:658-661.

120 Eucker J, Sezer O, Graf B, Possinger K. Mucormycoses. Mycoses. 2001;44:253-260.

121 Prabhu RM, Patel R. Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: a review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(Suppl 1):31-47.

122 Peterson KL, Wang M, Canalis RF, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: evolution of the disease and treatment options. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:855-862.

123 Pierce PFJr, Solomon SL, Kaufman L, et al. Zygomycetes brain abscesses in narcotic addicts with serological diagnosis. JAMA. 1982;248:2881-2882.

124 Tobon AM, Arango M, Fernandez D, et al. Mucormycosis (zygomycosis) in a heart-kidney transplant recipient: recovery after posaconazole therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1488-1491.

125 Dannaoui E, Meis JF, Loebenberg D, et al. Activity of posaconazole in treatment of experimental disseminated zygomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3647-3650.

126 Sutton DA, Fothergill AW, Rinaldi MG. Guide to Clinically Significant Fungi. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1997.

127 Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:781-803.

128 Walsh TJ, Hier DB, Caplan LR. Aspergillosis of the central nervous system: clinicopathological analysis of 17 patients. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:574-582.

129 Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Central nervous system aspergillosis: a 20-year retrospective series. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:116-124.

130 Torre-Cisneros J, Lopez OL, Kusne S, et al. CNS aspergillosis in organ transplantation: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:188-193.

131 Boes B, Bashir R, Boes C, et al. Central nervous system aspergillosis: analysis of 26 patients. J Neuroimaging. 1994;4:123-129.

132 Boon AP, Adams DH, Buckels J, et al. Cerebral aspergillosis in liver transplantation. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:114-118.

133 Woods GL, Goldsmith JC. Aspergillus infection of the central nervous system in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:181-184.

134 Jantunen E, Volin L, Salonen O, et al. Central nervous system aspergillosis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:191-196.

135 Romero Vidal FJ, Ortega Aznar A, Ibarra de Grassa B. Central nervous system aspergillosis: computed tomographic patterns and radiopathological correlation. Int J Neuroradiol. 1998;4:320-323.

136 Stynen D, Goris A, Sarfati J, et al. A new sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect galactofuran in patients with invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:497-500.

137 Machetti M, Zotti M, Veroni L, et al. Antigen detection in the diagnosis and management of a patient with probable cerebral aspergillosis treated with voriconazole. Transpl Infect Dis. 2000;2:140-144.

138 Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:358-366.

139 Stevens DA, Kan VL, Judson MA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for diseases caused by aspergillus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:696-709.