CHAPTER 24 Parasagittal and Falx Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Parasagittal meningiomas are interesting because of the technical challenges they present in resection and the changing concepts of their general management. Their usual location is in eloquent cortex, and the increasingly conservative surgical management is paradigmatic of a changing approach to meningiomas in general. Aggressive resection of these tumors means opening the superior sagittal sinus (SSS), removing tumor from within it, and somehow reconstituting the sinus. This has been advocated by some as the preferred surgical goal when the sinus is only partially occluded, with sinus repair and venous grafting when necessary.1–3 In the past, surgical techniques for assessing and safely grafting the sinus have been described.1,4

Recently there has been a different approach to these meningiomas. Resection of the sinus, although leading to lower rate of recurrence, increases the risk of hemorrhage, SSS thrombosis, or venous infarction leading to brain edema and neurologic deterioration. This approach has therefore been modified in recent years, with increasing use of radiosurgery as adjunctive treatment for residual tumors after resection of most of the meningioma.5 We have recently evaluated patients who underwent parasagittal meningioma resection at our institution. Our general approach to these tumors was to resect all tumor and dura involved outside the SSS, and closely follow the residual tumor in the sinus. Tumor progression was treated with radiosurgery.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Positioning

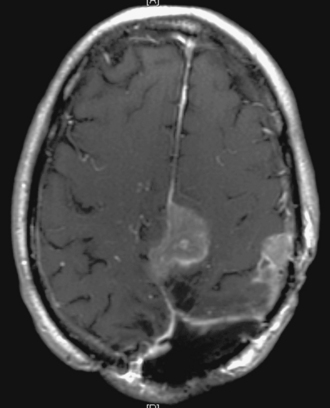

Our approach and positioning are chosen based on the segment of the SSS involved. The general concept is to have eloquent cortex fall away from the tumor by gravity. Patients with tumors involving the anterior third of the SSS are therefore positioned supine with the head flexed. Patients with tumors involving the middle third are positioned with the head turned to the side of the tumor so that gravity causes the brain to fall away from the tumor6 (Fig. 24-1). This usually eliminates the need for brain retraction. Patients with tumors involving the posterior third are positioned prone so that the motor cortex falls away by gravity.

Procedure

The veins associated with these tumors must be preserved at all costs.7,8 The safe surgery of parasagittal meningiomas is surgery of the veins that are associated with them. We undermine veins or gently dissect them off the tumor surface as we are debulking the tumor.

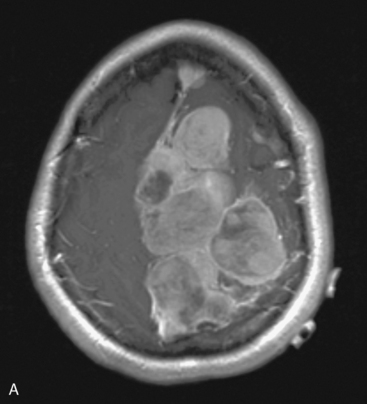

We begin tumor resection by internally debulking using Cavitron or loop cautery, doing our best to avoid retraction on the brain. We then separate the tumor from the brain circumferentially. Tumor invading the SSS is cauterized on the wall of the SSS. If the tumor is just in the wall of the sinus it is removed and the sinus is sutured as the tumor is removed; however, we do not try to reconstruct the sinus with a vein or other graft. Figure 24-2 shows an example of a large parasagittal meningioma removed using these techniques.

Several series have been published advocating aggressive surgical approaches to parasagittal meningiomas. Central to them is a classification of sinus involvement in meningiomas: Brotchi’s group has created a useful classification that was also used with slight modification in Sindou’s series:2,7,9

MANAGEMENT OF THE SAGITTAL SINUS

Sindou has published the most recent series using an aggressive approach to parasagittal meningiomas that includes sinus reconstruction when necessary.10 In his series, gross total removal was achieved in 93% of cases, with sinus reconstruction in 65% of the 69 cases demonstrating wall and lumen invasion. Patients with an 8-year follow-up after en bloc resection had a recurrence rate of 4%. There was, however, a mortality rate of 3%, and 8% of patients had permanent neurologic worsening from venous infarction. Based on these findings, Sindou and colleagues favored aggressive resection with sinus reconstruction using autologous grafts for tumors invading the wall of the sinus. However, patients were exposed to higher risk surgery, with nearly a third of the patients undergoing a two-stage procedure and all patients with sinus reconstruction requiring anticoagulation treatment after surgery. Bonnal and Brotchi advocated an aggressive approach to the sinus in an early publication;2 however, recently Professor Brotchi and his group have gravitated toward a more conservative approach.8 Dimeco and colleagues published a series of 108 patients in which they achieved Simpson grade 1 and 2 resection in 100 patients. They had a 13.9% recurrence rate, with most recurrences in the higher-grade tumors. Benign meningiomas had recurrence-free survival rate of 98% and 93%, in 5 and 10 years, respectively.3 Older series between 1978 and 1990 and with 5- to 10-year follow-up have reported recurrence rates between 8% and 23.9%.7–9,11,12 It is likely that certain features of tumor biology that have not yet been fully clarified are important in recurrence, although degree of resection is also important.13–15

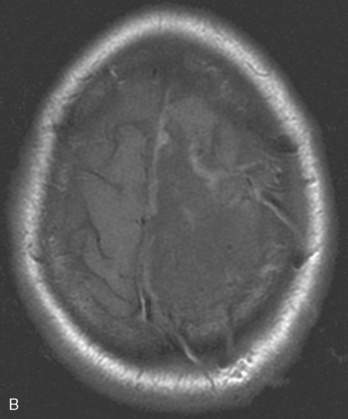

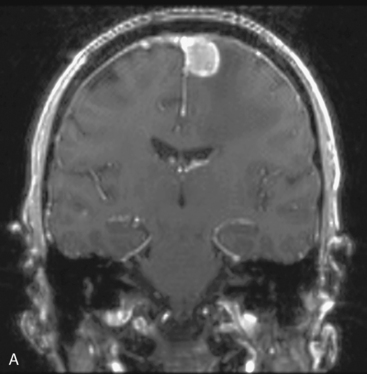

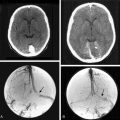

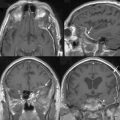

Based on the concept of avoiding direct deficit, there has been a general move to less aggressive surgery and the use of radiation to control tumor left in the sinus. Our series demonstrates the effect of a less aggressive surgical approach to parasagittal meningiomas. If the sinus was obliterated by tumor, the tumor and sinus were resected completely (see Fig. 24-2). If the tumor was adherent to the sinus wall, it was dissected away from it (see Fig. 24-1). The difficulty was encountered in such tumors as those shown in Figure 24-3: the problem is the possible patency of the sinus despite a major invasion. For these cases, we took a conservative approach. The patient was positioned with the tumor uppermost and the tumor was removed from cortex rather than retracting the brain (Fig. 24-4). Tumor was resected up to the sinus wall, and the sinus was left intact. Residual tumor was followed up and treated with radiosurgery for recurrence. In one case, a second surgery was needed because of failure of radiosurgery to control tumor growth. Although this approach led to a substantial number of postoperative residual tumors (36.8%), fewer than one third of those eventually progressed, and only three WHO grade 1 meningiomas (7.7%) progressed. In our series, in 55.6% of patients with a preoperative neurologic deficit, the deficit resolved after surgery and 5.5% had a new deficit. One elderly patient died within a month of surgery from a pulmonary embolus.

FIGURE 24-3 A parasagittal meningioma that appears to have occluded the sinus. The sinus should be able to be resected.

RADIATION THERAPY

In our series, 6% of cases required radiation within 5 years of their first surgery. Radiosurgery is a noninvasive means of treating residual tumor that is growing; it may in certain occasions be the first line of treatment. A large series was published by Kondziolka and colleagues, which included 203 patients who were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas.5 This series represents a change to radiosurgery as the primary treatment for these tumors. They had good results for radiosurgery as the first line of treatment, with 93 ± 4% tumor control rate. They had a lower control rate of 60 ± 10% for patients who had previous surgery. The control rate was 85% for the radiosurgery-treated volume. Radiosurgery was recommended for tumors less than 3 cm in diameter.

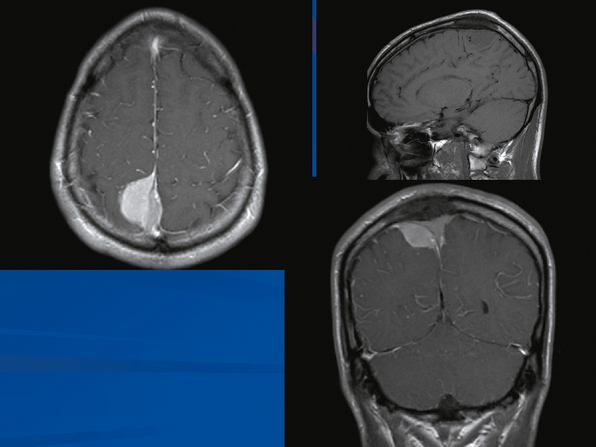

Figure 24-5 shows the effect of radiosurgery many years after it has been completed: the tumor is enhancing but is a stable remnant without change over 7 years.

OUTCOMES

We believe that a conservative approach to parasagittal meningiomas without aggressive resection of the sinus wall avoids potential thrombotic complications, and when undertaken with radiosurgery, has a very satisfactory long-term effect. For these and other meningiomas, the biology of the tumor may be as important as the degree of resection,13,14 and maximum safe resection followed by watchful waiting may be the most prudent approach.

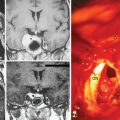

Falx Meningiomas

Falx meningiomas differ from parasagittal meningiomas in that the sagittal sinus is not involved in them (Fig. 24-6). They therefore represent a very different set of issues for the surgeon. For these, the major problem is localization and safe resection from the brain that is around them. Like parasagittal meningiomas, they tend to be in the central part of the brain in which the motor and sensory cortex are represented. It is extremely important to identify their location precisely and to approach them without retracting or otherwise hurting the brain that overlies them. For us, this means a navigation system to localize the tumor, positioning of the head to allow the cortex to fall away from the tumor, and minimal retraction on the brain adjacent to tumor. As with parasagittal tumors, great care must be taken with the veins that bridge from cortex to sagittal sinus; a preoperative MRI may be helpful in establishing where these veins are. Particular care must be taken with the cortex adjacent to the tumor, as this may be the foot area and is very unforgiving.15,16

CONCLUSIONS

The management of parasagittal and falx meningiomas has changed in the last decade. Tumors that are asymptomatic may be watched for growth with sequential MR scans. Tumors larger than 3 cm, producing symptoms, or with significant edema should be resected. For parasagittal tumors, the sinus need not be reconstructed; residual tumor on it can be treated with radiosurgery. For falx tumors, the major problem is avoiding problems with the surrounding brain and veins as the tumor is approached. Tumor biology must be taken into consideration as well as surgery for these important meningiomas.17

[1] Bederson J.B., Eisenberg M.B. Resection and replacement of the superior sagittal sinus for treatment of a parasagittal meningioma: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:1015-1018. discussion 1018–19

[2] Bonnal J., Brotchi J. Surgery of the superior sagittal sinus in parasagittal meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1975;48:935-945. 1978

[3] DiMeco F., Li K.W., Casali C., et al. Meningiomas invading the superior sagittal sinus: surgical experience in 108 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1263-1272. discussion 1272–4

[4] Schmid-Elsaesser R., Steiger H.J., Yousry T., et al. Radical resection of meningiomas and arteriovenous fistulas involving critical dural sinus segments: experience with intraoperative sinus pressure monitoring and elective sinus reconstruction in 10 patients. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:1005-1016. discussion 1016–8

[5] Kondziolka D., Flickinger J.C., Perez B. Judicious resection and/or radiosurgery for parasagittal meningiomas: outcomes from a multicenter review. Gamma Knife Meningioma Study Group. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:405-413. discussion 413–4

[6] Shevach I., Cohen M., Rappaport Z.H. Patient positioning for the operative approach to midline intracerebral lesions: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(1):154-155.

[7] Giombini S, Solero CL, Lasio G, Morello G. Immediate and late outcome of operations for Parasagittal and falx meningiomas. Report of 342 cases. Surg Neurol 21:427–43.

[8] Hancq A., Baleriaux D., Brotchi J. Surgical treatment of parasagittal meningiomas. In: Meningiomas; Contemporary Treatment. Seminars in Neurosurgery. 14(3), 2004.

[9] Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22-39.

[10] Sindou M.P., Alvernia J.E. Results of attempted radical tumor removal and venous repair in 100 consecutive meningiomas involving the major dural sinuses. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:514-525.

[11] Nowak A., Marchel A. Surgical treatment of parasagittal and falx meningiomas. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2007;41(4):306-314.

[12] Yamasaki F., Yoshioka H., Hama S., et al. Recurrence of meningiomas. Cancer. 2000;89:1102-1110.

[13] Jaaskelainen J., Haltia M., Servo A. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: radiology, surgery, radiotherapy, and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:233-242.

[14] Modha A., Gutin P.H. Diagnosis and treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: a review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:538-550. discussion 538–50

[15] Pimentel J., Fernandes A., Pinto A.E., et al. Clear cell meningioma variant and clinical aggressiveness. Clin Neuropathol. 1998;17:141-146.

[16] Kropp F., La Motta A., Landucci C., et al. [Recurrence of parasagittal meningioma after surgical treatment]. Riv Neurobiol. 1978;24:236-242.

[17] Schiffer D., Ghimenti C., Fiano V. Absence of histological signs of tumor progression in recurrence of completely resected meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2005;73:125-130.