Chapter 251 Parainfluenza Viruses

Epidemiology

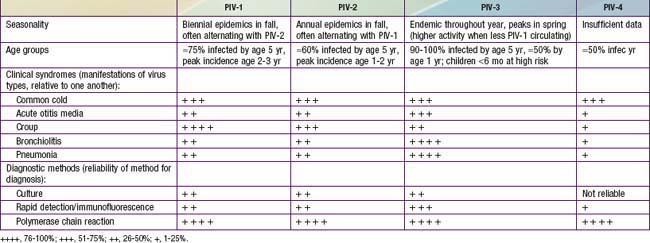

By 5 yr of age, most children have experienced primary infection with PIV types 1, 2, and 3 (Table 251-1). PIV-3 infections often occur in the first 6 mo of life, whereas PIV-1 and PIV-2 are more common after infancy. In the USA and temperate climates, PIV-1 and PIV-2 have biennial epidemics in the fall, usually alternating years in which their serotype is most prevalent. PIV-3 is endemic throughout the year but typically peaks in late spring. In years with less PIV-1 activity, the PIV-3 season may extend longer or have a second peak in the fall. The epidemiology of PIV-4 is less well defined, because it is difficult to grow in tissue culture and was often excluded from early studies.

Clinical Manifestations

Most PIV infections manifest themselves primarily in the upper respiratory tract (see Table 251-1). The most common types of illness consist of some combination of low-grade fever, rhinorrhea, cough, pharyngitis, and hoarseness and may be associated with vomiting or diarrhea. Rarely, PIV infection has been associated with parotitis. The illnesses usually last 4-5 days. The generally mild illness pattern is belied by a spectrum of rarer but more serious illnesses that result in hospitalization. PIVs account for 50% of hospitalizations for croup and at least 15% of cases of bronchiolitis and pneumonia. PIV-1 and to a lesser extent PIV-2 cause more cases of croup, whereas PIV-3 is more likely to infect the small air passages and cause pneumonia, bronchiolitis, or bronchitis. Any PIV can cause lower respiratory tract disease, particularly during primary infection or in immunosuppressed patients.

Laboratory Findings

Conventional laboratory diagnosis of infection is accomplished by PIV isolation in tissue culture. Direct immunofluorescent (IF) staining is available in some centers for rapid identification of virus antigen in respiratory secretions. Many laboratories perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) viral genomic testing, which greatly increases sensitivity of PIV detection (see Table 251-1). For viral culture or IF, a nasal wash or aspirate provides the best sample, but for PCR, nasal swabs are also appropriate.

Treatment

There are no approved treatments for PIV infections with the exception of croup. For croup, the possibility of rapid respiratory compromise should influence the acuity of care given (Chapter 377). Humidified air has not been shown to be effective. Generally a single dose of oral, intramuscular, or intravenous dexamethasone (0.6 mg/kg) should be part of the management of croup in the office or emergency room setting. This dose may be repeated, but there are no guidelines to compare outcomes of single- and multiple-dose treatment schedules. Nebulized epinephrine (either racemic epinephrine 2.25%, 0.5 mL in 2.5 mL of saline, or L-epinephrine, 1:1000 dilution in 5 mL of saline) may also provide temporary symptomatic improvement. Children should be observed for at least 2 hr after receiving epinephrine treatment for return of obstructive symptoms. Repeated treatments may obviate the need for intubation. Oxygen should be administered for hypoxia, and supportive care with analgesics and antipyretics is reasonable for fever and discomfort associated with PIV infections. The indications for antibiotics are limited to well-documented secondary bacterial infections of the middle ear(s) or lower respiratory tract.

Cherry JD. Clinical practice: croup. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:384-391.

Chonmaitree T, Revai K, Grady JJ, et al. Viral upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media complication in young children. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:815-823.

Fry AM, Curns AT, Harbour K, et al. Seasonal trends of human parainfluenza viral infections: United States, 1990–2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1016-1022.

Henrickson KJ. Parainfluenza viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:242-264.

Lau SK, To WK, Tse PW, et al. Human parainfluenza virus 4 outbreak and the role of diagnostic tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4515-4521.

Loughlin GM, Moscona A. The cell biology of acute childhood respiratory disease: therapeutic implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:929-959.

Nichols WG, Peck Campbell AJ, Boeckh M. Respiratory viruses other than influenza virus: impact and therapeutic advances. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:274-290.

Reed G, Jewett PH, Thompson J, et al. Epidemiology and clinical impact of parainfluenza virus infections in otherwise healthy infants and young children <5 years old. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:807-813.

Sato M, Wright PF. Current status of vaccines for parainfluenza virus infections. Pediatr Infec Dis J. 2008;27:S123-S125.

Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Iwane MK, et al. Parainfluenza virus infection of young children: estimates of the population-based burden of hospitalization. J Pediatr. 2009;154:694-699.