Chapter 155 Paracoccygeal Transsacral Approach to the Lumbosacral Junction for Interbody Fusion and Stabilization

The interbody space can be approached from the ventral, dorsal, and direct lateral approaches. Each of these approaches has its limitations. Anterior interbody fusions allow for the instrumentation to be placed along the long axis of the spine, which has been shown to demonstrate favorable biomechanics, because the instrumentation is placed close to the instantaneous axis of rotation of the spine and perpendicular to the compressive moments of the vertebral bodies. The ventral exposure techniques to the lumbosacral segment have evolved from transperitoneal to retroperitoneal and even laparoscopic approaches. However, these exposures require mobilization of the abdominal contents and vascular structures, and this carries an element of risk and also frequently involves specialized expertise to perform the exposure safely. The use of interbody implants with these exposures necessitates partial resection of the anulus to place the implant. This, in turn, may contribute to a destabilizing effect on the spine despite the use of a specific implant. In response to the limitations of these contemporary exposures and techniques for lumbosacral fusions, Cragg et al.1 recently described a novel percutaneous, fluoroscopically guided, access method to the lumbosacral junction. The access is gained through a paracoccygeal incision with blunt dissection through the presacral space, all while the patient is positioned prone. This approach allows for axial transsacral access to the lumbosacral junction. Along with this exposure, specially designed tools to evacuate the disc space, prepare the end plates, and introduce graft material, as well as a specialized axial stabilization rod, have all been developed to facilitate a minimally invasive fusion of the lumbosacral junction.

Presacral Anatomy

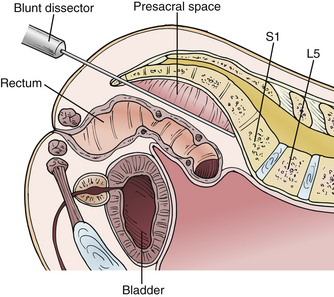

The paracoccygeal presacral access to the lumbosacral junction takes advantage of a well-defined anatomic potential space between the anterior surface of the sacrum and posterior surfaces of the sigmoid colon and rectum (Fig. 155-1). This presacral space is bounded by visceral fascia on the sigmoid colon and rectum and by parietal fascia on the anterior surface of the sacrum. The presacral space is filled with areolar tissue and fat. The rectum and sigmoid colon are not attached to any structures in the course of the presacral space; therefore, they can be easily mobilized with a blunt dissector. It is important to keep the dissection limited to the midline presacral space. The sacral nerve roots exit the foramina and course laterally and inferiorly, away from the midline presacral space. Because this space is devoid of any significant vascular or neurologic elements, there are no obstacles to establishing a corridor for access.

Yuan et al. studied the anatomic relationships of the presacral space.2 These investigators reported that at the lumbosacral junction the iliac vessels and their accompanying sympathetic hypogastric nerves coursed laterally over the sacral ala. In the midline just beyond the lumbosacral junction, the midline sacral artery and vein follow a variable course and typically terminate in a fine reticular mesh. They defined the coronal safe zone at the S1-2 interspace as more than 6 cm wide in both males and females on the basis of CT and MRI measurements. Therefore, at the typical docking and entry point into the sacral promontory, which is usually at the S1-2 junction, there are no significant obstructions.

Parke et al. described the variability of the middle sacral artery in 20 cadavers, reporting that in humans, it is only a minor contributor to any major segmental arteries, through bilateral segmental branches.3 Furthermore, it was found to be absent in many specimens. Using 10 cadavers and MRI studies, Güvençer et al. measured the distances between the sacrum and the presacral structures (i.e., middle and lateral sacral arteries, sympathetic trunks, internal iliac arteries and veins, and colon/rectum).4 This cadaver study showed that the middle sacral artery was located on the right side in 55.0% of cases, on the left side in 31.7%, and on the midline in the 13.3%. The distance between the sacral midline and middle sacral artery was 8.0 ± 5.4, 9.0 ± 4.9, 8.7 ± 6.0, 8.6 ± 6.4, and 4.7 ± 5.0 mm at the S1-2, S2-3, S3-4, S4-5, and S5-coccyx levels, respectively. The distance between the sacral midline and the sympathetic trunk ranged between 22.4 ± 5.8 and 9.5 ± 3.2 mm in different levels between the S1 and coccygeal levels. The study also showed that the distance between the posterior wall of the intestine (colon/rectum) and the ventral surface of the sacrum can be as close as 11.44 ± 7.69 mm on MRI. Because of the close relationships, as well as the potential for anatomic variations, the authors recommended the use of sacral and presacral imaging before a presacral approach. Oto et al.5 described the sagittal width of the presacral space at the S1, S2, and S3 vertebral levels retrospectively on MRI in 193 patients. The researchers found that (1) the presacral width in males was significantly wider than in females and (2) in general, the presacral space was at least 1 cm wide in more than 60% of males and 40% of females.

Evolution of Technique

The paracoccygeal presacral access to the lumbosacral junction was validated in a series of cadaver, animal, and human trials. Cragg et al., in a series of 15 cadavers, refined the access technique and the necessary instruments.1 The instruments evolved to include dissectors, cannulae, drills, discectomy tools, bone graft application tools, and axial rod implantation tools. The investigators validated the procedure with a fully percutaneous fluoroscopic approach through a single 2-cm paracoccygeal incision. Cragg et al. then assessed the safety of the access procedure in a series of six consecutive animals.1 The access was performed without adverse events. Lumbosacral access in the animals was confirmed fluoroscopically by axial discography. Following the success of the preclinical studies, the researchers undertook a series of consecutive biopsies of the lumbosacral disc and vertebral body region for suspected pathologic lesions in three patients.1 Again, the technique posed no significant issues.

Surgical Procedure

Preoperative Planning

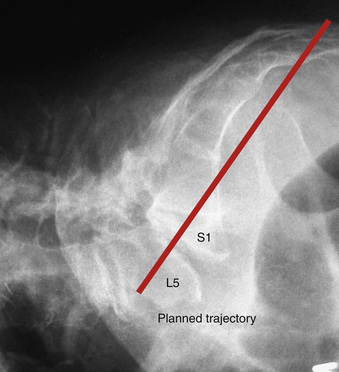

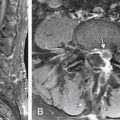

In preparation for the surgical approach, the radiographic images, including a full sacral view, are analyzed to determine if the anatomy is suitable for the paracoccygeal transsacral approach to the lumbosacral junction. The standard field of view for a lumbar MRI scan should be expanded to include the entire sacrum and coccyx on the sagittal views. With the radiographs and MRI scans, one can plan and map the trajectory of the access and subsequent implantation of the axial rod (Fig. 155-2).

Patient Preparation

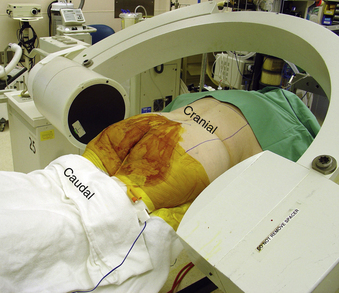

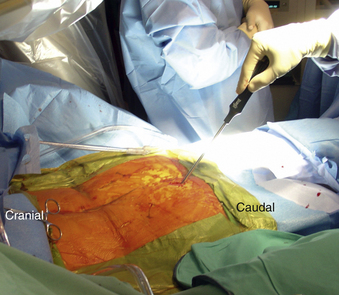

Typically, a standard bowel preparation the evening before surgery is advisable. In the operating room, the patient is positioned prone onto a radiolucent table with the lumbar spine in extension to facilitate lumbar lordosis. The lumbar and the sacrococcygeal regions are prepped and draped. The operative area should be isolated from the anus with an occlusive dressing (Fig. 155-3).

Operating Room Setup

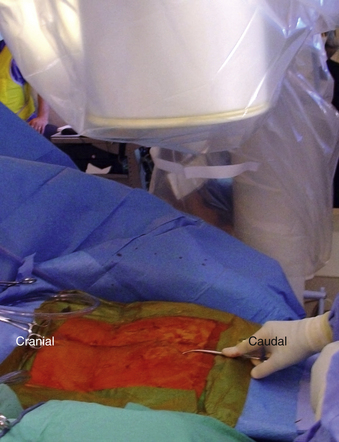

Once the patient is positioned, two image intensifiers are positioned for simultaneous biplanar fluoroscopy. The posteroanterior C-arm should be adjusted to project a lordotic view of the lumbosacral junction. The lateral C-arm should be adjusted to achieve a true lateral view of the lumbosacral junction. The lateral and anteroposterior C-arms should be draped such that they can move in a parallel fashion from the tip of the coccyx to the lumbosacral junction freely as needed throughout the procedure (Fig. 155-4).

Access and Trajectory Planning

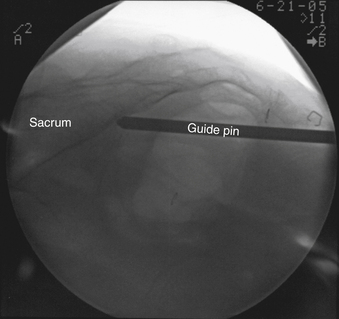

To begin, it is necessary to palpate the coccyx and sacrotuberous ligament arch and then create a 15- to 20-mm incision through the skin and superficial fascia 2 to 3 cm caudal to the paracoccygeal notch and left or right of the coccyx (Fig. 155-5). After making the initial 2-cm paracoccygeal skin incision, a Kelly clamp is used to bluntly dissect down to the parietal fascia. Penetrating the fascia is necessary to access the presacral space and the anterior face of the sacrum. Penetrating the fascia can be accomplished using finger dissection, blunt guide pin dissection, or a combination of the two. Once achieved, the blunt guide pin is then advanced in a cephalic direction under fluoroscopic guidance in the midline, keeping the tip engaged on the anterior cortex of sacrum to approximately the S1-2 junction (Fig. 155-6). This maneuver is accomplished with “fingertip” control on the handle of the guide pin introducer and should be completed using fluoroscopic guidance in both anteroposterior and lateral planes.

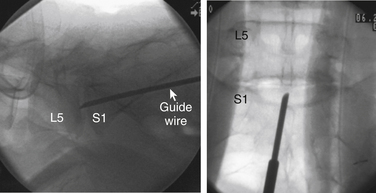

Centerline Trajectory

Once the guide pin has reached the S1-2 junction, a midline trajectory for entry into and through the L5-S1 disc space is established by adjusting the angle of the guide pin. The aim is to traverse the L5-S1 disc space in its midpoint in both the posteroanterior and lateral planes. Once the trajectory is established, an exchange system is used to switch the blunt guide pin for a bevel tip extended K-wire. The bevel tip K-wire is then advanced across the disc space, keeping its predetermined trajectory (Fig. 155-7).

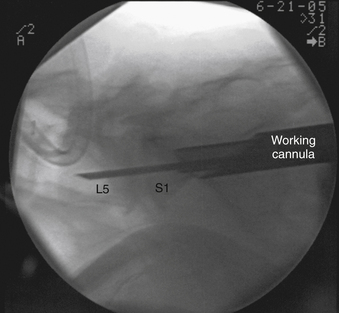

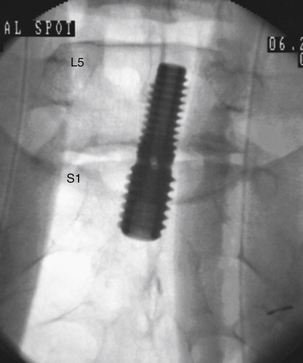

Working Cannula and Disc Space Preparation

Once the guidewire is situated, a series of instruments is used to dilate the soft tissue and sacral corticocancellous bone sequentially to create the working channel and to dock the working cannula (Fig. 155-8). Following this, several tools are used to prepare the disc space for fusion. These include specially designed radial cutters and brushes (Fig. 155-9).

Preparing to Implant the Axial Rod

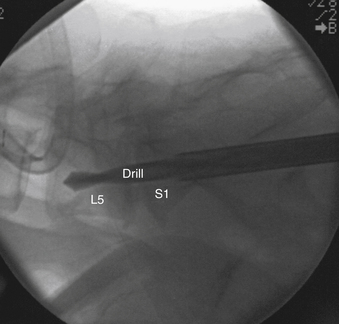

At this point, a drill is advanced across the disc space and into the L5 vertebral body to create a channel to accommodate the axial rod. The depth of the drilling is guided with the fluoroscopic views (Fig. 155-10).

Potential Complications

To date, more than 2000 cases using a paracoccygeal exposure have been performed worldwide.6 Experience with this technique is still too limited to comment accurately on the magnitude of risk associated with it and the various potential complications. However, the possible complications that may be encountered as they relate to the surgical access include infection, injury to the presacral structures, fracture of the sacral promontory, and inaccurate trajectory or placement of the implants.

Outcomes

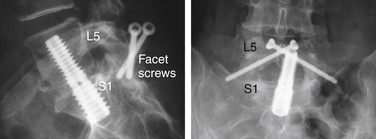

Both biomechanical and clinical investigations have been performed. A biomechanical study using human cadaveric lumbar spine designed to evaluate the biomechanics of paracoccygeal transsacral rod fixation has been performed by Akesen et al.7 Unconstrained and nondestructive pure moments in axial torsion (AT), lateral bending (LB), and flexion-extension (FE) were applied to each specimen after applying a transsacral rod and after additional augmentation methods, including bilateral screws, facet screws, and a pedicle screw and rod system. Range of motion (ROM) was calculated for each surgical treatment. The mean ROM of the intact specimens was 3.5, 6.4, and 11.0 degrees in AT, LB, and FE, respectively. The stand-alone transsacral rod reduced ROM more than 40% compared with the intact condition (P = .002). Bilateral screws further reduced the ROM in AT (64%) and LB (70%) but not in FE (53%). Both facet screws and the pedicle screw and rod system achieved high construct stability under all loading conditions. The transsacral rod augmented with facet screws reduced ROM by 70%, 80%, and 90% in AT, LB, and FE, respectively, compared with the intact condition. When augmented with the pedicle screw and rod system, the transsacral rod reduced ROM by 73%, 87%, and 88% in AT, LB, and FE, respectively. There was no statistical difference between the two facet screws and the pedicle screw and rod system. The authors concluded that the transsacral rod fixation provides strong ligamentotaxis due to intact anulus. The stand-alone transsacral rod is able to reduce ROM significantly and achieve indirect decompression by distracting the L5-S1 disc space. However, additional posterior fixation, such as facet screws or pedicle screws, is required to achieve better construct stability.

The feasibility of a two-level transsacral rod has been evaluated by Erkan et al.8 Unconstrained and nondestructive pure moments in AT, LB, and FE were applied to each specimen following intact, stand-alone transsacral rod, and transsacral rod with two posterior fixation options—facet screws and pedicle screws with rods. At the L4-5 level in AT and FE, none of the surgical treatments showed a statistically significant difference between the procedures, although facet screws and pedicle screws had higher stability on average. In LB, the two posterior fixation techniques had significantly higher construct stability than the stand-alone rod. No significant difference was found between facet screws and pedicle screws. At the L5-S1 level in AT and LB, none of the surgical treatments were found to be statistically significant. In FE, the stand-alone two-level transsacral rod had significantly higher ROM compared with the posterior fixation techniques. The authors concluded that the stand-alone rod reduced intact ROM significantly. However, they recommended supplementary fixations, including facet screws and pedicle screws, to increase construct stability.

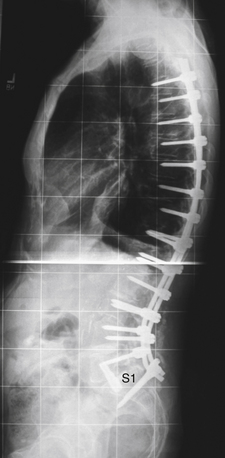

In a prospective evaluation of 12 patients undergoing surgery for lumbar degenerative scoliosis, Anand et al. evaluated the feasibility of a transsacral rod placed at L5-S1 as an alternative to traditional anterior or posterior transsacral fixation.9 Short-term follow-up demonstrated that this technique is a potential minimally invasive option for patients undergoing long instrumented fusions to the sacrum.

Aryan et al. reviewed these investigators’ experience with the transsacral interbody fusion in 35 patients.10 Average follow-up was 17.5 months. All patients had radiographic evidence of L5-S1 degeneration and underwent percutaneous paracoccygeal axial fluoroscopically guided interbody fusion with cage, local bone autograft, and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP). Mean operative time for the L5-S1 paracoccygeal transsacral procedure was 42 minutes. Twenty-one patients underwent transsacral interbody fusion followed by percutaneous L5-S1 pedicle screw-rod fixation. Two patients underwent transsacral interbody fusion followed by percutaneous L4-5 lateral psoas splitting interbody fusion and posterior instrumentation. Ten patients had a stand-alone procedure. Unfavorable anatomy precluded access to the L5-S1 disc space during open lumbar interbody fusion in two patients who subsequently underwent transsacral rod instrumentation at this level as part of a large construct. Thirty-two patients (91%) had radiographic evidence of stable L5-S1 interbody cage placement and fusion at the last follow-up.

Asgarzadie et al. reported on 28 consecutive patients who underwent paracoccygeal transsacral interbody fusion.11 Follow-up averaged 1 year. The operative time averaged 45 minutes, the estimated blood loss was minimal in all cases, and the hospital stay averaged 24 hours. There was an average 26-point decrease between preoperative and postoperative Oswestry Disability Index scores and a 7-point decrease in visual analogue scale scores at 1-year follow-up; these results were statistically significant. The rate of fusion was 90% at 1 year (16/16 patients with bone morphogenetic protein had radiologic fusion at 1 year). The investigators noted no complications.

Summary

The paracoccygeal transsacral exposure technique represents another option for minimally invasive access to the lumbosacral junction. This approach can be used either for primary lumbar fusions (Fig. 155-12) or as an extension of long fusions (Fig. 155-13) across the lumbosacral junction. The approach is associated with minimal soft tissue trauma, which could potentially result in faster postoperative recovery. It may serve as an alternative approach to the L5-S1 interspace in those patients who may have unfavorable anatomy or other contraindications to traditional open techniques. Currently, no randomized prospective studies exist that validate the advantages of this technique.

Akesen B., Wu C., Mehbod A., et al. Biomechanical evaluation of paracoccygeal transsacral fixation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(1):39-44.

Anand N., Baron E., Thaiyananthan G., et al. Minimally invasive multilevel percutaneous correction and fusion for adult lumbar degenerative scoliosis: a technique and feasibility study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(7):459-467.

Cragg A., Carl A., Casteneda F., et al. New percutaneous access method for minimally invasive anterior lumbar surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17(1):21-28.

Parke W., Whalen J., Van Demark R., et al. The infra-aortic arteries of the spine: their variability and clinical significance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(1):1-5.

Yuan P., Day T., Albert T., et al. Anatomy of the percutaneous presacral space for a novel fusion technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(4):237-241.

1. Cragg A., Carl A., Casteneda F., et al. New percutaneous access method for minimally invasive anterior lumbar surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17(1):21-28.

2. Yuan P., Day T., Albert T., et al. Anatomy of the percutaneous presacral space for a novel fusion technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(4):237-241.

3. Parke W., Whalen J., Van Demark R., Kambin P. The infra-aortic arteries of the spine: their variability and clinical significance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(1):1-5.

4. Güvençer M., Dalbayrak S., Tayefi H., et al. Surgical anatomy of the presacral area. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009;31(4):251-257.

5. Oto A., Peynircioglu B., Eryilmaz M., et al. Determination of the width of the presacral space on magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Anat. 2004;17(1):14-26.

6. Company data. TranS1 Inc, Wilmington, NC.

7. Akesen B., Wu C., Mehbod A., Transfeldt E. Biomechanical evaluation of paracoccygeal transsacral fixation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(1):39-44.

8. Erkan S., Wu C., Mehbod A., et al. Biomechanical evaluation of a new AxiaLIF technique for two-level lumbar fusion. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(6):807-814.

9. Anand N., Baron E., Thaiyananthan G., et al. Minimally invasive multilevel percutaneous correction and fusion for adult lumbar degenerative scoliosis: a technique and feasibility study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(7):459-467.

10. Aryan H., Newman C., Gold J., et al. Percutaneous axial lumbar interbody fusion (AxiaLIF) of the L5-S1 segment: initial clinical and radiographic experience. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51(4):225-230.

11. Asgarzadie F., Khoo L., Cosar M., et al. One year outcomes of minimally invasive presacral approach and instrumentation technique for anterior lumbosacral intervertebral discectomy and fusion. Proceedings of the 22nd CNS Annual Meeting. Spine J. 2007;7(55):S26-S27. [Special Interest Paper Presentations 4: Fusion]