Pancreatitis

Acute Pancreatitis

Aetiology and epidemiology of acute pancreatitis

Gallstones and alcoholism together account for about 80% of acute pancreatitis worldwide. These and the other main causes of acute pancreatitis are listed in Table 25.1 (see also Boxes 25.1 and 25.2). Opie first pointed out the relationship between gallstones and pancreatitis in 1901 based on autopsy evidence. Small gallstones may cause transient obstruction as they pass through the ampulla via the bile ducts, or larger stones may impact at the lower end of the common bile duct, resulting in pancreatic duct obstruction. Beyond this, the precise mechanism of gallstone pancreatitis remains obscure.

Table 25.1

Aetiology of acute pancreatitis

| Condition | Frequency |

| Obstruction | |

| Gallstones | 30–70% of cases |

| Congenital abnormalities: pancreas divisum with accessory duct obstruction; choledochocoele; duodenal diverticula | 5% of cases |

| Ampullary or pancreatic tumours | 3% of cases |

| Abnormally high pressure in the sphincter of Oddi (over 40 mmHg) | 1–2% of cases |

| Ascariasis (second most common cause in endemic areas, e.g. Kashmir) | Depends on locality |

| Drugs and toxins | |

| Alcohol excess | 30–70% of cases |

| Drugs: (‘SAND’—Steroids and sulphonamides, Azathioprine (and 6-mercaptopurine), NSAIDs, Diuretics such as furosemide and thiazides, and didanosine); also antibacterials such as metronidazole and tetracycline, H2 blockers and many other classes of drug | 1–2% |

| Scorpion venom | Very rare |

| Snake bites | Very rare |

| Iatrogenic and traumatic causes | |

| Following endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) or endoscopic sphincterotomy | 2–6% of patients having the procedure |

| Following cardiopulmonary bypass | 0.5–5% of patients having bypass |

| Blunt pancreatic trauma, usually due to motor vehicle accidents | Very rare |

| Repeated marathon running | Very rare |

| Metabolic causes | |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia (> 11 mmol/L) | 2% of cases |

| Hypercalcaemia | Rare |

| Hypothermia | Rare |

| Pregnancy | Rare |

| Infection | |

| AIDS: secondary infection with cytomegalovirus and others | About 10% in patients with AIDS |

| Other viruses: mumps, chickenpox, Coxsackie viruses, hepatitis A, B and C | Very rare |

| Idiopathic pancreatitis | |

| No definable cause after thorough diagnostic evaluation including ERCP; research studies show about two-thirds of ‘idiopathic’ cases have gallstone microlithiasis | 10–12% of cases |

Pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis

As severity increases, trypsin and other enzymes cause increasingly extensive local damage as well as activation of complement and cytokine systems leading on to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and organ failure. Manifestations include shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Ch. 2). At this stage, acute peripancreatic fluid collections become detectable on CT. The most severe pancreatitis is associated with pancreatic necrosis. Ischaemia within the gland plus reperfusion injury are likely mechanisms in transforming acute oedematous pancreatitis into this necrotising disease. Complications are common and mortality in this group (even without infection) is as high as 10%.

Investigation of suspected pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis must be excluded in any adult presenting with acute abdominal pain, and in any child with peritonitis not readily attributable to appendicitis. The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and other organisations have produced comprehensive guidelines on the management of acute pancreatitis: (http://www.bsg.org.uk/pdf_word_docs/pancreatic.pdf).

Plasma amylase: Amylase is one of the enzymes released into the circulation in pancreatitis; measurement is a simple laboratory investigation and is generally a reliable diagnostic test. A level above 1000 i.u. /ml is usually regarded as diagnostic of acute pancreatitis but levels are often lower in alcoholic pancreatitis, particularly during recurrent attacks. Any inflammatory upper abdominal condition near the pancreas (e.g. cholecystitis, perforated peptic ulcer or strangulated bowel) can cause a moderate rise in amylase, although this rarely reaches 1000 i.u. /ml. Levels rise rapidly at the outset of an attack, and readings of 10 000 i.u./ml or more may be recorded on admission to hospital. However, levels fall as the patient recovers so a diagnosis of pancreatitis should not rely on an arbitrary threshold; rather the amylase level at any moment should be interpreted in relation to how much time has elapsed since the onset.

Imaging: Plain X-rays of chest (erect) to look for free gas under the diaphragm, and abdomen (supine) are usually performed during the initial investigation. The latter may show a featureless ‘ground-glass’ appearance. Bowel gas tends to be absent except perhaps for a ‘sentinel loop’ of dilated adynamic small bowel in the centre. Note, however, that these signs are not specific for pancreatitis and are often absent. Rarely, radiopaque gallstones are visible.

Endoscopy: In patients with severe acute gallstone pancreatitis, urgent ERCP and sphincterotomy should be carried out within 72 hours of the onset of pain. This is especially important in patients with cholangitis, jaundice or a dilated common bile duct. ERCP also has an important diagnostic role once the patient has fully recovered from the acute attack if a cause for pancreatitis is not evident from the history or initial imaging studies. In this group, a cause can be found in about 50%, e.g. small pancreatic or periampullary tumours, pancreatic duct stricture, gallstones, congenital pancreas divisum or a high-pressure sphincter of Oddi.

Clinical classification

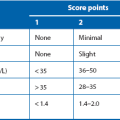

To provide early warning of severity, each patient with acute pancreatitis is sorted into one of two categories, mild or severe. This provides an indicator of prognosis within the first 48 hours, and is central to formulating a management strategy. Categorisation is based on thoroughly tested scoring systems originally developed by Ranson in USA (see Box 25.4) and modified by Imrie (Glasgow criteria—see Table 25.2). If three or more of the factors listed are present, the patient is diagnosed as having severe pancreatitis and should be admitted to an intensive care or high-dependency unit for careful monitoring. The more adverse factors present, the worse the prognosis. Even if a patient is initially placed in the mild group, continued observation is essential as deterioration to severe pancreatitis can occur at any time. The clinical features of acute pancreatitis are summarised in Box 25.3.

Table 25.2

A mnemonic (‘PANCREAS’) for remembering the modified Glasgow scoring system of severity prediction in acute pancreatitis (After E M Moore, with permission*)

| Mnemonic letter | Criterion | Positive when |

| P | PaO2 | < 8 kPA or 60 mmHg |

| A | Age | > 55 years |

| N | Neutrophil count | > 15 × 109/L |

| C | Calcium (blood) | < 2 mmol/L |

| R | Raised plasma urea | > 16 mmol/L |

| E | Enzyme (plasma lactate dehydrogenase, LDH) | > 600 i.u./L |

| A | Albumin (plasma) | < 32 g/L |

| S | Sugar (plasma glucose) | > 10 mmol/L |

*E Moore A useful mnemonic for severity stratification in acute pancreatitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2000; 82: 16–17

Mild acute pancreatitis: Mild attacks are common. The patient looks generally well with minimal systemic features. Nevertheless, there is often considerable pain. The abdomen is usually distended and diffusely tender but with little guarding. Bowel sounds are absent as a result of inflammatory ileus. The patient may be mildly jaundiced from periampullary oedema. The differential diagnosis includes biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, an acute exacerbation of a peptic ulcer or even a perforation of a peptic ulcer. Lower lobe pneumonia or an inferior myocardial infarction may sometimes present like this. Sometimes the pancreatitis diagnosis is made after plasma amylase is unexpectedly found to be elevated.

Severe acute pancreatitis: In a severe attack the patient looks apathetic, grey and shocked and there are typical abdominal signs of generalised peritonitis, i.e. extreme tenderness, guarding and rigidity. In this case, the differential diagnosis includes other major abdominal catastrophes, especially faecal peritonitis from perforated large bowel and concealed haemorrhage from a leaking aortic aneurysm or ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Massive bowel infarction due to arterial occlusion may present like this but abdominal signs are less marked. An important early and dangerous complication of severe acute pancreatitis is acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Management of acute pancreatitis

Mild attacks: The management of acute pancreatitis has been the subject of several international consensus conferences, the most important of which took place in Atlanta in 1992. This codified many definitions and circumstances within acute pancreatitis. Another important consensus meeting was in Washington in 2004. Numerous sets of guidelines are available; in the UK, the most used are published by BSG, updated in 2005.

Severe attacks: A severe attack is defined by referring to a specified list of criteria which should be evaluated on admission and over the next 48 hours (see Table 25.2 and Box 25.4). Patients with severe pancreatitis may die early in the attack because of profound systemic toxaemia (SIRS), shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS); see Chapter 3, p. 51. ARDS develops rapidly with little warning but a deteriorating arterial PO2 may herald its onset. This is an indication for urgent ventilatory support before the condition becomes established.

Gross fluid and electrolyte disturbances as well as hypocalcaemia are also likely to occur. Fluid balance in the shocked patient is complicated by massive losses of protein-rich fluid into the peritoneal cavity and interstitially (‘third space’). This sequestration of fluid needs to be countered by large amounts of intravenous fluids, carefully monitored by measuring central venous pressure and hourly urine output. Any patient with severe pancreatitis, or anyone with acute pancreatitis who develops signs of serious deterioration, should be admitted to an intensive care unit for close monitoring and vigorous treatment of cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal and septic complications. Box 25.5 lists recommended investigations to guide management.

Endoscopy and surgery in severe acute pancreatitis: All patients suspected of having or proven to have a gallstone aetiology should undergo urgent therapeutic ERCP, which should take place within 72 hours of the onset of pain. This applies whether severe pancreatitis is predicted or confirmed. All of these patients require sphincterotomy of the sphincter of Oddi whether or not stones are found in the common bile duct. If stones are seen or if cholangitis or jaundice is present, biliary stenting is usually required.

Complications of acute pancreatitis

Mortality: About 15% of patients admitted to hospital with acute pancreatitis have severe disease, which carries a high risk of potential complications. However, about a further 10% initially diagnosed with mild pancreatitis deteriorate markedly during admission and become severe. In severe pancreatitis, mortality is 10–30%, i.e. 2–5% of all cases, and obese patients have a higher mortality. About half of those that die, do so within the first week, usually of ARDS and pulmonary failure. Other early life-threatening complications are associated with multiple organ dysfunction (MODS). Manifestations include cardiovascular collapse aggravated by fluid shifts, renal insufficiency made worse by hypotension, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. If death occurs after the first week, infective complications of pancreatic necrosis added to existing organ failure are the usual cause.

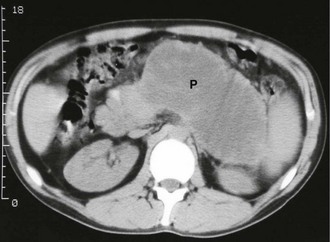

Pancreatic necrosis and infection: In severe pancreatitis, pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis may manifest during the first 2 weeks of the attack (see Fig. 25.1). Necrosis is identified using intravenous contrast-enhanced CT scanning in which necrotic pancreas does not opacify, having lost its blood supply. Infection of devitalised pancreatic and peripancreatic tissues occurs in about one-third of patients with severe pancreatitis, and is often lethal. Infection may be suspected on CT by gas bubbles in pancreatic fluid collections but can only be confirmed by percutaneous aspiration (with microscopy and culture of the aspirate), usually performed under CT guidance. In proven infected cases, operative debridement, drainage and sometimes continuous peritoneal irrigation may be necessary, along with aggressive organ support.

Fluid collections around the pancreas: During the initial attack, acute peripancreatic fluid collections may develop. Most resolve spontaneously, but for those that do not, CT-guided percutaneous drainage is valuable. Fluid collections persisting for longer than 6 weeks are termed pancreatic pseudocysts (see below). Late in the course of the disease, a pancreatic abscess may appear. This is a well-localised collection of pus within the gland, and contrasts with infected necrotising pancreatitis which appears earlier and is not localised.

Pancreatic pseudocyst: A pancreatic pseudocyst is a collection of pancreatic enzymes, inflammatory fluid and necrotic debris, usually encapsulated within the lesser sac. Pseudocysts appear in 1–8% of cases of acute pancreatitis and are less likely to resolve spontaneously than the early acute fluid collections. A pseudocyst is not a true cyst (i.e. there is no epithelial lining) although the surrounding tissues become thickened by the inflammatory response. Pseudocysts may occur after even a moderate attack of pancreatitis and sometimes reach the size of a football! An upper abdominal mass may be palpable. If a pseudocyst is suspected, CT scanning is the investigation of choice (see Fig. 25.2).

Pancreatic abscess: Pancreatic abscesses occur in 1–4% of cases of acute pancreatitis. Certain patients remain systemically well despite pancreatic necrosis, with an illness that may grumble on for several weeks. There is a recurrent high swinging fever indicating the presence of an abscess. By that time, the necrotic pancreas is likely to have formed a discrete grey mass lying free within the pancreatic bed and bathed in pus. Pus may extend widely in retroperitoneal tissues. Surgery is then required to remove the necrotic tissue and drain the abscesses.

Complications of severe acute pancreatitis: Severe acute pancreatitis can cause wide-ranging complications in almost every body system:

• Multi-organ failure may lead to renal failure, respiratory failure, cardiac failure, and haematological and coagulation disorders

• Direct pressure effects, inflammation and hypotension may cause portal vein thrombosis

• Local pressure plus hypotension may cause bowel ischaemia—the transverse colon is commonly affected because of the position of the middle colic artery

• Pseudoaneurysms may form in vessels such as the splenic artery because of inflammatory damage to the arterial wall and fluid collections around them

• Internal pancreatic fistulae may form, particularly if necrosis causes disruption of the pancreatic duct or the wall of a pseudocyst. The result may be pancreatic ascites, mediastinal pseudocysts, enzymatic mediastinitis or pancreatic pleural effusions

Recurrent and Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis

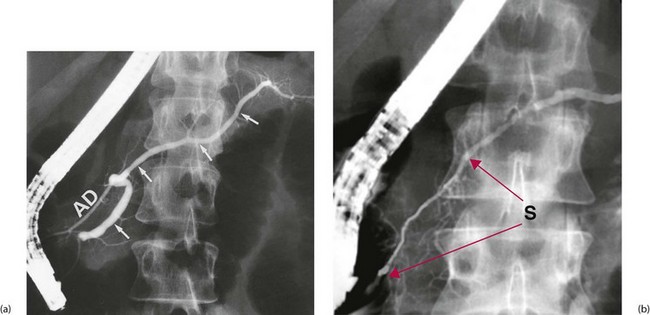

In chronic pancreatitis, ultrasound or CT scans may show glandular swelling (sometimes difficult to differentiate from pancreatic carcinoma) and a dilated pancreatic duct. If ERCP is performed, the pancreatic duct system may look normal or else may be distorted and irregular in calibre, confirming chronic inflammation and fibrosis (see Fig. 25.3). Sometimes pancreatic duct stones are shown.

Pancreatic calcification seen on abdominal X-rays is diagnostic of chronic pancreatitis but is a rare finding and is sometimes found in asymptomatic patients (see Fig. 25.4). X-rays are therefore of little clinical value.