Secondary signs of pancreatic injury are usually present (peripancreatic fat stranding and fluid, thickening of pararenal fascia, peripancreatic hematoma)

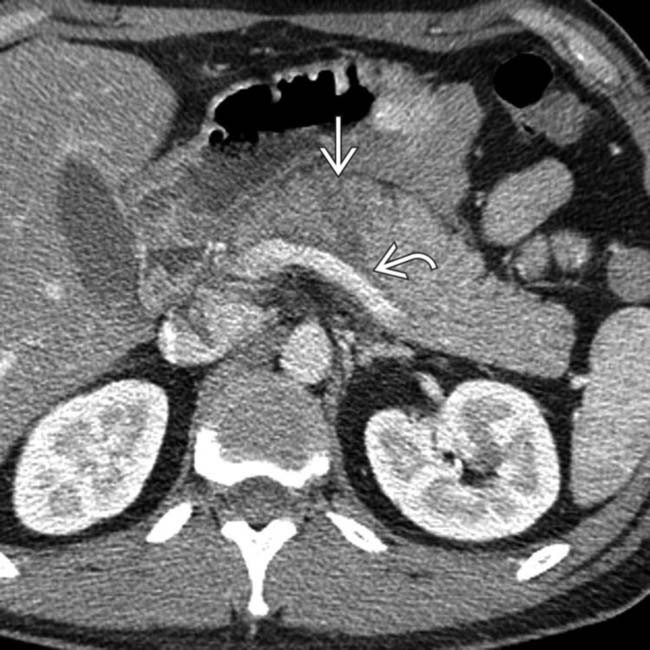

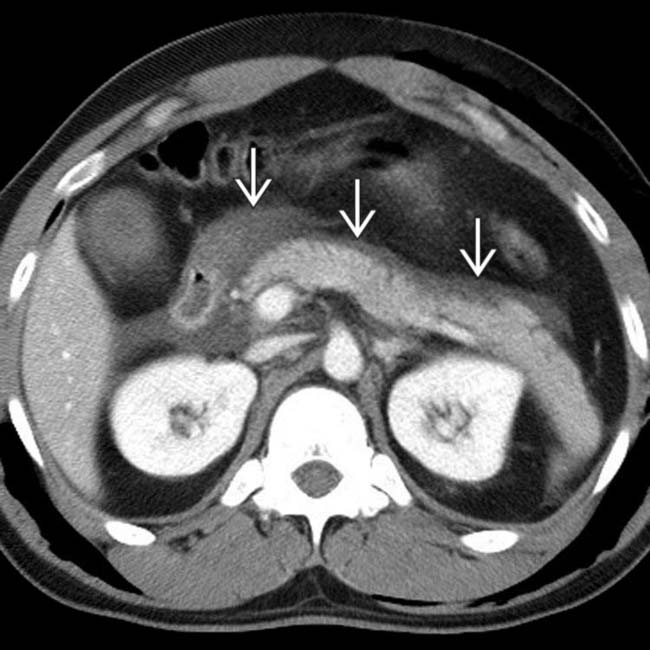

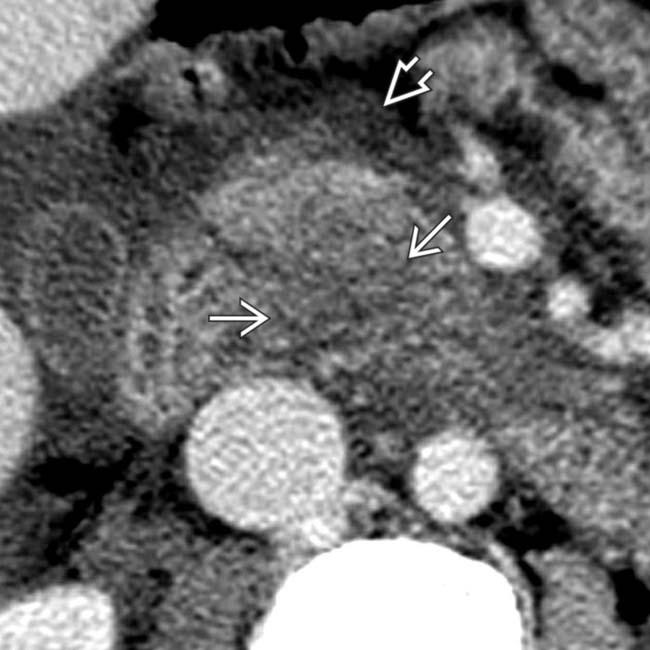

Pancreatic contusion: Ill-defined focal hypoattenuation at site of injury (not linear like laceration)

Pancreatic contusion: Ill-defined focal hypoattenuation at site of injury (not linear like laceration)

with fluid in the lesser sac

with fluid in the lesser sac  as well as retropancreatic fluid

as well as retropancreatic fluid  .

.

tracking posterior to the pancreas along the splenic vein from extravasated pancreatic juice. Secondary signs of injury, such as peripancreatic fluid, hematoma, or fat stranding, are almost always present as a clue to the diagnosis.

tracking posterior to the pancreas along the splenic vein from extravasated pancreatic juice. Secondary signs of injury, such as peripancreatic fluid, hematoma, or fat stranding, are almost always present as a clue to the diagnosis.

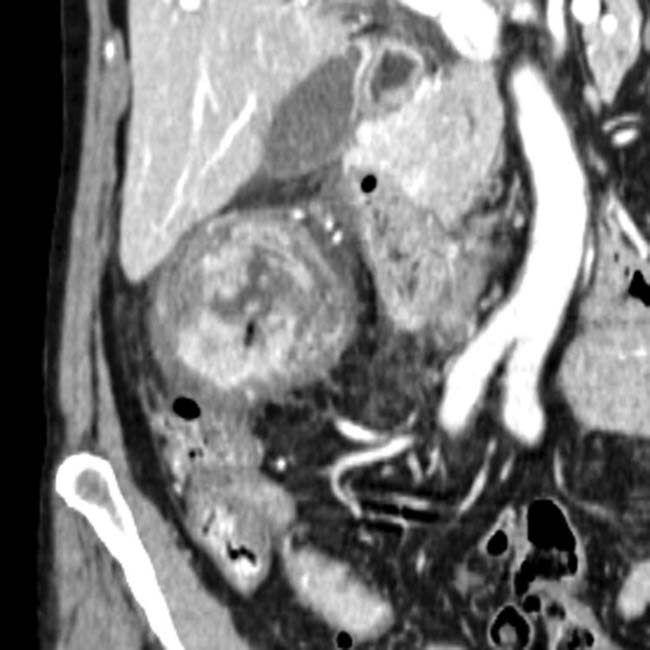

through the neck of the pancreas. The pancreatic duct was disrupted, and the body and tail of the pancreas were resected at surgery.

through the neck of the pancreas. The pancreatic duct was disrupted, and the body and tail of the pancreas were resected at surgery.

in the lesser sac in this pancreatic transection

in the lesser sac in this pancreatic transection  .The fluid collection developed as a result of leakage of fluid from the site of the transected pancreatic duct.

.The fluid collection developed as a result of leakage of fluid from the site of the transected pancreatic duct.IMAGING

General Features

CT Findings

• Secondary signs of pancreatic injury or post-traumatic pancreatitis usually present even in absence of discrete contusion/laceration

Peripancreatic fat stranding and fluid with loss of normal peripancreatic fat planes almost always present

Peripancreatic fat stranding and fluid with loss of normal peripancreatic fat planes almost always present

Peripancreatic fat stranding and fluid with loss of normal peripancreatic fat planes almost always present

Peripancreatic fat stranding and fluid with loss of normal peripancreatic fat planes almost always present

• Pancreatic contusion: Ill-defined focal hypoattenuation at site of injury

• Pancreatic laceration: Discrete linear cleft of hypoattenuation running through pancreas (usually perpendicular to long-axis of gland)

Often associated with distortion or irregularity of contour of pancreas and hypoenhancement of gland upstream from laceration

Often associated with distortion or irregularity of contour of pancreas and hypoenhancement of gland upstream from laceration

Often associated with distortion or irregularity of contour of pancreas and hypoenhancement of gland upstream from laceration

Often associated with distortion or irregularity of contour of pancreas and hypoenhancement of gland upstream from lacerationDIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Shock Pancreas

• Part of hypoperfusion complex seen in severe traumatic injuries or in setting of severe hypotension

• Abnormally intense enhancement of pancreas, bowel wall, and kidneys, with decreased caliber of aorta and inferior vena cava, and diffuse dilatation of intestine with fluid

PATHOLOGY

General Features

• Etiology

May result from either penetrating or blunt trauma

May result from either penetrating or blunt trauma

May result from either penetrating or blunt trauma

May result from either penetrating or blunt trauma

– Mechanism in blunt trauma

Most commonly the result of motor vehicle collisions, but also falls, crush injuries, and assaults (with direct blow to abdomen)

Most commonly the result of motor vehicle collisions, but also falls, crush injuries, and assaults (with direct blow to abdomen)

Pancreatic injuries in children often due to blunt trauma, including trauma from bicycle handlebar, motor vehicle crash, or child abuse

Pancreatic injuries in children often due to blunt trauma, including trauma from bicycle handlebar, motor vehicle crash, or child abuse

Usually result from anterior/posterior compression force to abdomen (more rarely lateral force vector)

Usually result from anterior/posterior compression force to abdomen (more rarely lateral force vector)

Most commonly the result of motor vehicle collisions, but also falls, crush injuries, and assaults (with direct blow to abdomen)

Most commonly the result of motor vehicle collisions, but also falls, crush injuries, and assaults (with direct blow to abdomen) Pancreatic injuries in children often due to blunt trauma, including trauma from bicycle handlebar, motor vehicle crash, or child abuse

Pancreatic injuries in children often due to blunt trauma, including trauma from bicycle handlebar, motor vehicle crash, or child abuse Usually result from anterior/posterior compression force to abdomen (more rarely lateral force vector)

Usually result from anterior/posterior compression force to abdomen (more rarely lateral force vector)CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

Treatment

• AAST grades III, IV, and V (blunt trauma): Require surgery within 24 hours

Grade III: Usually distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (with spleen preservation in children), although pancreas may be preserved with “clean” pancreatic lacerations

Grade III: Usually distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (with spleen preservation in children), although pancreas may be preserved with “clean” pancreatic lacerations

Grade III: Usually distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (with spleen preservation in children), although pancreas may be preserved with “clean” pancreatic lacerations

Grade III: Usually distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (with spleen preservation in children), although pancreas may be preserved with “clean” pancreatic lacerations

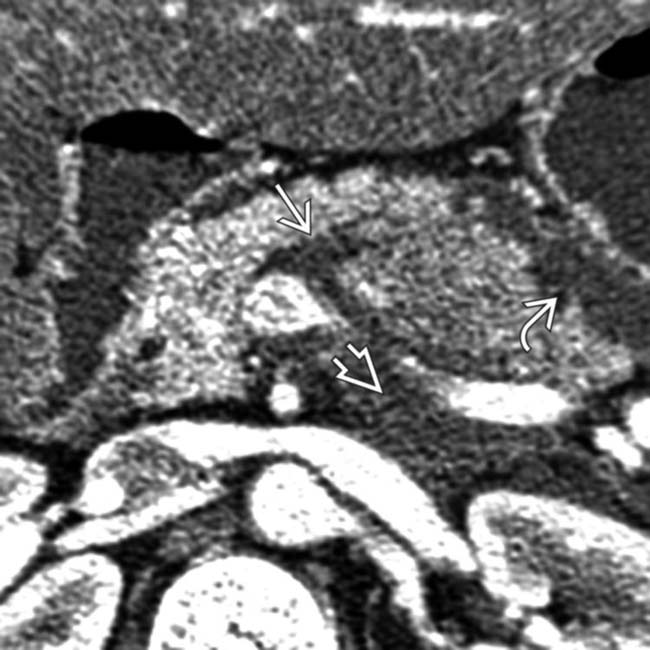

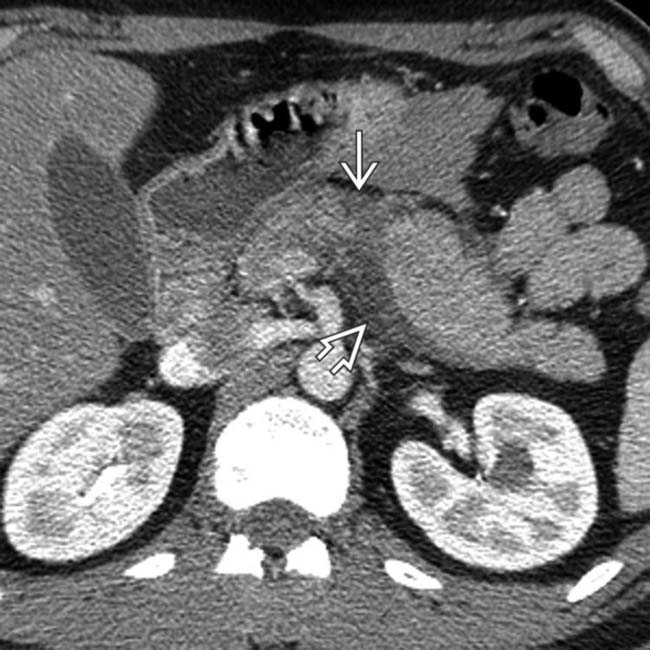

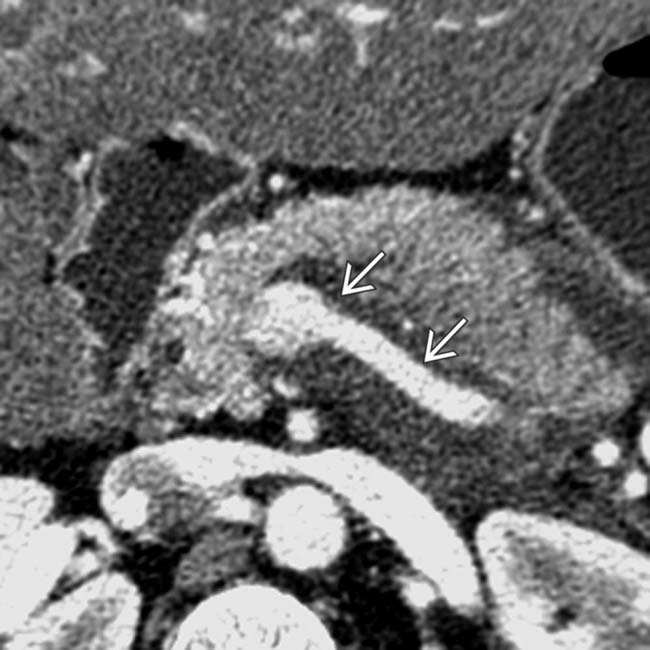

. Note the subtle retropancreatic fluid

. Note the subtle retropancreatic fluid  adjacent to the splenic vein.

adjacent to the splenic vein.

and more obvious adjacent peripancreatic fluid

and more obvious adjacent peripancreatic fluid  . In some patients, retropancreatic fluid is the most conspicuous sign of a pancreatic fracture.

. In some patients, retropancreatic fluid is the most conspicuous sign of a pancreatic fracture.

and a perirenal fluid collection

and a perirenal fluid collection  .

.

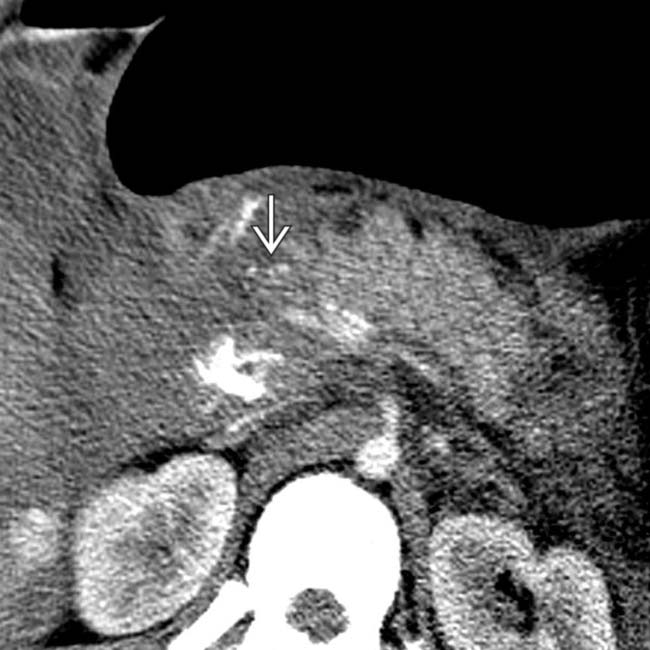

with fluid in the pancreatic groove

with fluid in the pancreatic groove  . Note the adjacent shock bowel

. Note the adjacent shock bowel  , which is thickened and hyperenhancing.

, which is thickened and hyperenhancing.

, in keeping with this patient’s pancreatic contusion. No discrete laceration was visualized.

, in keeping with this patient’s pancreatic contusion. No discrete laceration was visualized.

. While no parenchyma laceration was detected by CT, the isolated peripancreatic fluid, particularly in the presence of elevated serum lipase and amylase, is highly suggestive of a pancreatic injury.

. While no parenchyma laceration was detected by CT, the isolated peripancreatic fluid, particularly in the presence of elevated serum lipase and amylase, is highly suggestive of a pancreatic injury.

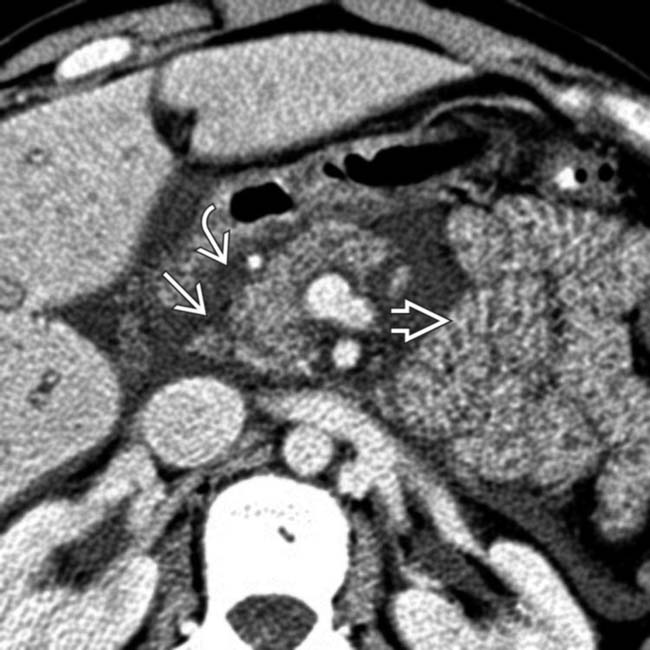

in the mid body of the pancreas and adjacent fluid in the lesser sac

in the mid body of the pancreas and adjacent fluid in the lesser sac  .

.

posterior to the pancreas and anterior to the splenic vein.

posterior to the pancreas and anterior to the splenic vein.

in the mid body of the pancreas.

in the mid body of the pancreas.

. in the anterior pararenal space.

. in the anterior pararenal space.

in the head of the pancreas.

in the head of the pancreas.

. Note the surrounding peripancreatic fluid and blood

. Note the surrounding peripancreatic fluid and blood  .

.

and a large surrounding hematoma

and a large surrounding hematoma  .

.

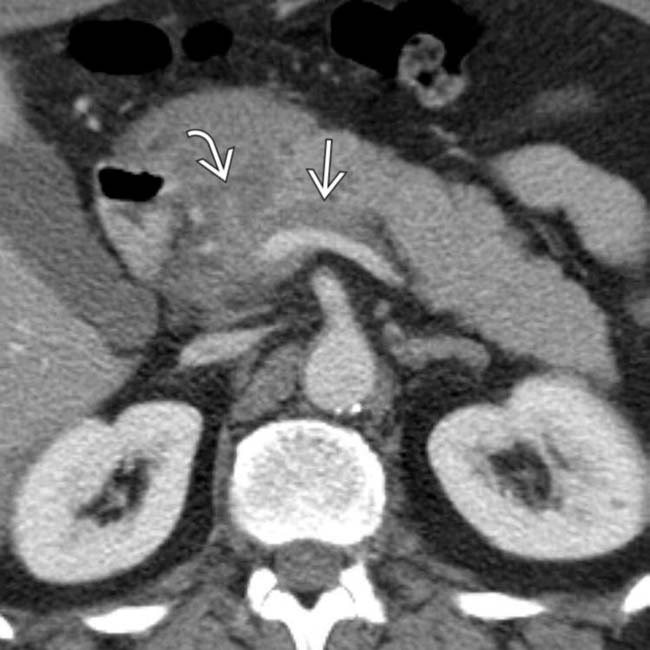

through the neck and body of the pancreas.

through the neck and body of the pancreas.

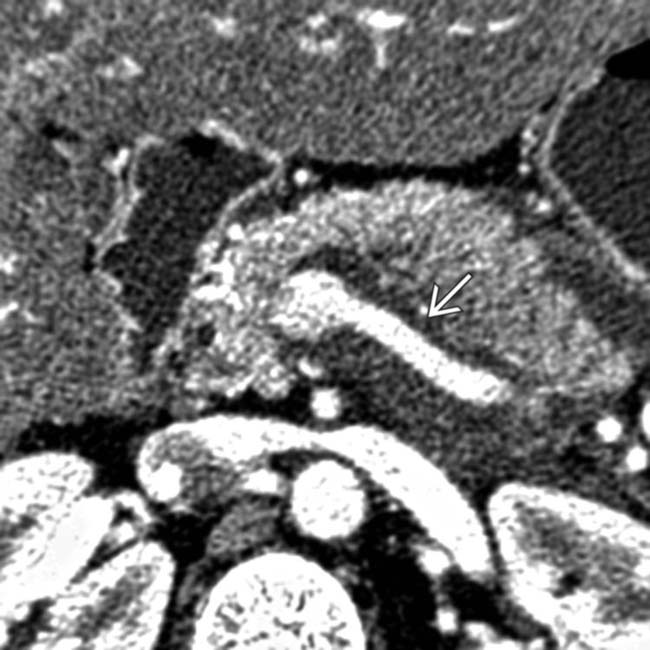

at the pancreatic neck as well as fluid

at the pancreatic neck as well as fluid  between the splenic vein and pancreatic body.

between the splenic vein and pancreatic body.

and hematoma in the body of the pancreas.

and hematoma in the body of the pancreas.

completely through the pancreatic neck.

completely through the pancreatic neck.

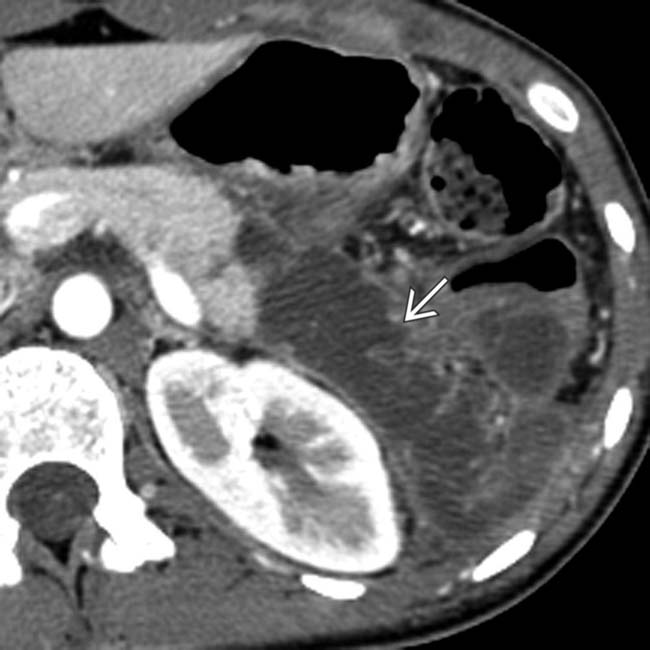

. Note the small amount of fluid posterior to the stomach in the lesser sac

. Note the small amount of fluid posterior to the stomach in the lesser sac  . There are subtle linear areas of decreased enhancement within the body of the pancreas representing a laceration

. There are subtle linear areas of decreased enhancement within the body of the pancreas representing a laceration  .

.

anterior to the splenic vein indicating a pancreatic injury. Note also the hemoperitoneum in the left paracolic gutter from the splenic fracture

anterior to the splenic vein indicating a pancreatic injury. Note also the hemoperitoneum in the left paracolic gutter from the splenic fracture  .

.

in the tail of the pancreas that was not detected at the time of initial surgical exploration. Note the surgically placed drain

in the tail of the pancreas that was not detected at the time of initial surgical exploration. Note the surgically placed drain  in the pancreatic bed and a small amount of peripancreatic fluid

in the pancreatic bed and a small amount of peripancreatic fluid  near the pancreatic tail.

near the pancreatic tail.

extends through the entire tail of the pancreas thus representing a pancreatic fracture. Note also the peripancreatic fluid

extends through the entire tail of the pancreas thus representing a pancreatic fracture. Note also the peripancreatic fluid  .

.

to the neck of the pancreas with an adjacent high-density hematoma

to the neck of the pancreas with an adjacent high-density hematoma  in the pancreatic groove.

in the pancreatic groove.

as well as the pancreatic groove

as well as the pancreatic groove  .

.

and adjacent fluid

and adjacent fluid  in the groove between the head of the pancreas and the 2nd duodenum.

in the groove between the head of the pancreas and the 2nd duodenum.

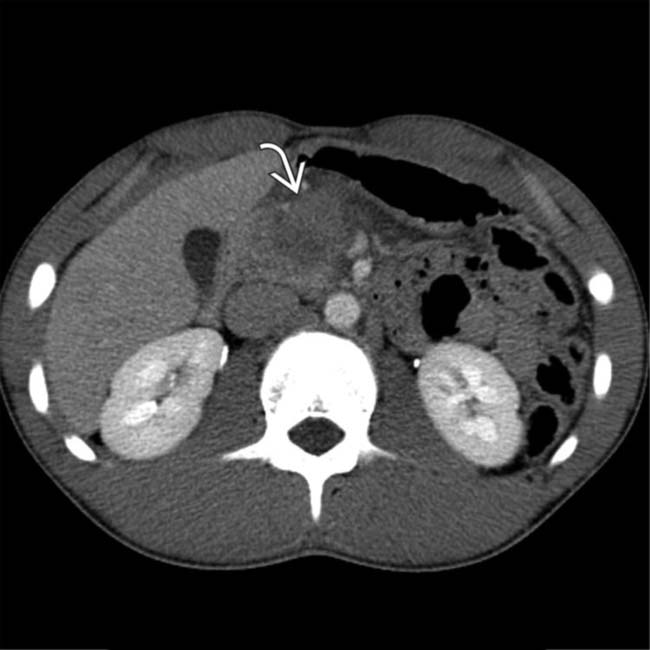

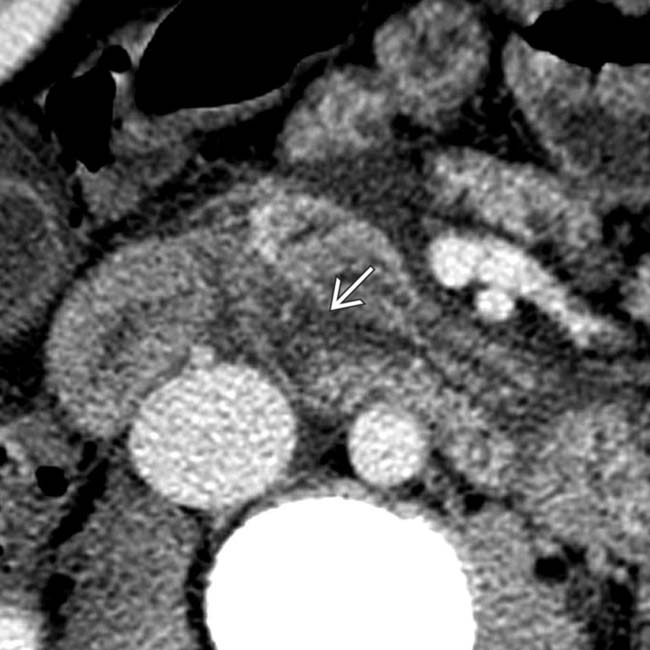

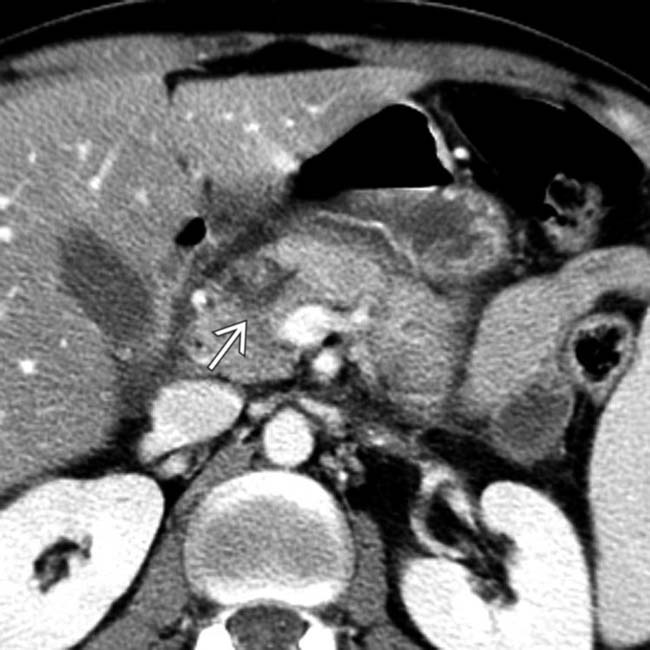

of retroperitoneal and mesenteric fat planes surrounding the pancreas, not explainable by liver injury. In addition, note the hypodense fluid

of retroperitoneal and mesenteric fat planes surrounding the pancreas, not explainable by liver injury. In addition, note the hypodense fluid  between the pancreas and splenic vein. The patient had several days of abdominal pain and elevation of serum amylase and lipase. However, there was no development of a pancreatic pseudocyst or sign of disruption of the pancreatic duct. The patient was managed without surgery and was sent home in good condition after a few days.

between the pancreas and splenic vein. The patient had several days of abdominal pain and elevation of serum amylase and lipase. However, there was no development of a pancreatic pseudocyst or sign of disruption of the pancreatic duct. The patient was managed without surgery and was sent home in good condition after a few days.

in pancreatic body, indicative of pancreatic contusion, possibly laceration. Note peripancreatic stranding

in pancreatic body, indicative of pancreatic contusion, possibly laceration. Note peripancreatic stranding  consistent with pancreatitis.

consistent with pancreatitis.

involving the head and neck of the pancreas.

involving the head and neck of the pancreas.

evident as irregular hypodense plane through right lobe.

evident as irregular hypodense plane through right lobe.

and thick-walled, vividly enhancing small bowel

and thick-walled, vividly enhancing small bowel  , consistent with shock bowel.

, consistent with shock bowel.

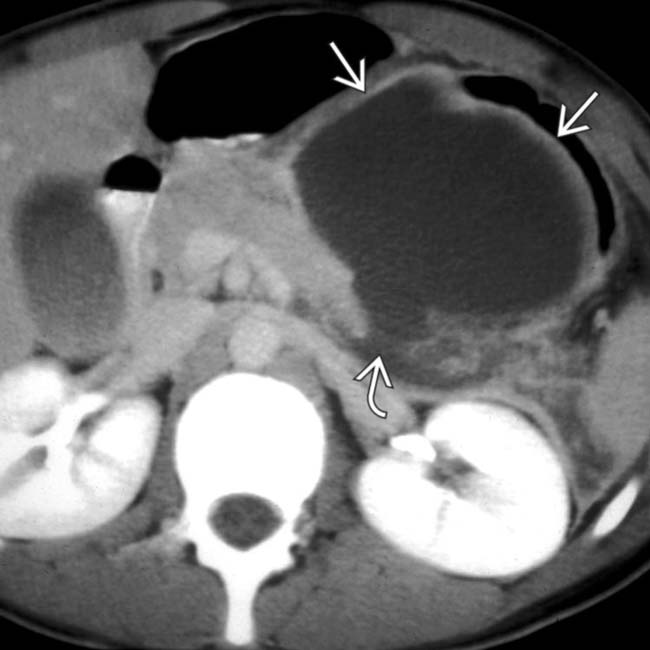

through the body of the pancreas. There is a small fluid collection in the lesser sac

through the body of the pancreas. There is a small fluid collection in the lesser sac  .

.