Pancreatic endocrine tumors

1. What are the pancreatic endocrine tumors?

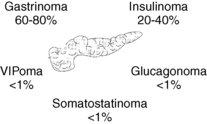

Tumors that arise from the islet cells of the pancreas are generally named for the hormones they secrete. These include tumors that secrete insulin (insulinomas), gastrin (gastrinomas), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIPomas), glucagon (glucagonomas), somatostatin (somatostatinomas), pancreatic polypeptide (PPomas), corticotropin-releasing factor (CRFomas), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTHomas), and growth hormone–releasing factor (GRFomas) (Fig. 53-1).

Figure 53-1. Pancreatic islet-cell tumors.

2. Are pancreatic endocrine tumors usually benign or malignant?

Insulinomas are usually benign (80%–90%); other pancreatic endocrine tumors are frequently malignant (50%–80%).

3. Are pancreatic endocrine tumors associated with other endocrine disorders?

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) syndrome accounts for up to 10% of pancreatic endocrine tumors. This inherited disorder consists of pituitary tumors, pancreatic endocrine tumors, and hyperparathyroidism. Hyperparathyroidism usually precedes the pituitary and pancreatic tumors by years. The condition is caused by an inherited mutation in the menin gene.

Insulinomas are discrete insulin-producing tumors within the pancreas. They belong to a larger group of hyperinsulinemic pancreatic beta-cell disorders that include insulinomas, islet-cell hyperplasia, and nesidioblastosis (neoproliferation of beta cells along the pancreatic ducts).

6. What glucose levels are considered to be hypoglycemia?

Glucose levels lower than 55 mg/dL are commonly considered to be hypoglycemic, but the best criteria for hypoglycemia continue to be controversial.

7. What are the symptoms of hypoglycemia?

Hypoglycemic symptoms are classified by their type and timing in relation to meals. Neuroglycopenic symptoms (confusion, slurred speech, blurred vision, seizures, coma) result from inadequate glucose delivery to the brain. Adrenergic symptoms (tremors, sweating, palpitations, nausea) result from catecholamine discharges. Symptoms that occur within 5 hours after a meal are termed postprandial; those occurring more than 5 hours after meals are considered fasting. Neuroglycopenic symptoms are characteristic of insulinomas, but adrenergic symptoms may also occur. Insulinomas most commonly cause fasting hypoglycemia (73%), although both fasting and postprandial hypoglycemia (21%) and pure postprandial hypoglycemia (6%) may be seen.

8. What evaluation should be done to test for an insulinoma?

Blood samples can be obtained during an episode of witnessed hypoglycemia, or the conditions that provoke the hypoglycemia must be replicated. This is most commonly done with a prolonged fast (supervised 72-hour fast or outpatient 12- to 18-hour fast). For this procedure, patients are allowed to drink calorie-free, caffeine-free beverages only. Blood is drawn every 6 hours until the glucose is less than 60 mg/dL, and then every 1 to 2 hours. Sufficient blood is obtained for measurement of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin, and beta-hydroxybutyrate; glucose is measured immediately on all samples, and the other tests are run only on samples for which the glucose is lower than 55 mg/dL. Insulin antibodies are ordered on one sample, and a urine screen is sent for sulfonylureas and meglitinides. The test is stopped when the patient has typical symptoms, when the glucose level is less than 45 mg/dL (or <55 mg/dL if Whipple’s triad was previously demonstrated) or at the end of 72 hours. At the end of the test, glucagon 1 mg is given intravenously, and glucose is measured 10, 20, and 30 minutes later.

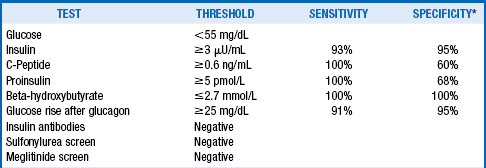

9. What are the diagnostic criteria for an insulinoma?

Hypoglycemia with endogenous hyperinsulinemia must be demonstrated to diagnose an insulinoma. Diagnostic criteria are shown in Table 53-1.

TABLE 53-1.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR INSULINOMA: DEMONSTRATION OF HYPOGLYCEMIA WITH ENDOGENOUS HYPERINSULINEMIA

*Compared with normal controls who developed glucose <60 mg/dL during a 72-hour fast.

Adapted from Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al: Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:709–728, 2009; and KA Placzkowski, A Vella, GB Thompson, et al: Secular trends in the presentation and management of functioning insulinoma at the Mayo Clinic, 1987–2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:1069–1073, 2009.

10. How can an insulinoma be localized?

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually the first localization procedure; reported sensitivities of these techniques vary from 15% to 90%. Endoscopic ultrasound of the pancreas has higher sensitivity (56%–93%) and can detect tumors as small as 2 to 3 mm. Intraarterial pancreatic calcium infusions with measurement of insulin changes in the right hepatic vein yield similar or superior results. Intraoperative ultrasound is highly accurate and useful for finding small tumors that could not be localized preoperatively.

11. What is the treatment for an insulinoma?

Surgery is the treatment of choice. When surgery is not desired or feasible, symptom relief can often be achieved with dietary management (multiple small meals per day) and medical therapy to inhibit insulin secretion with diazoxide, somatostatin analogs (octreotide, lanreotide), or calcium channel blockers. Malignant insulinomas can show partial responses to cytotoxic chemotherapy (streptozotocin with doxorubicin or 5-fluorouracil). Other considerations may include everolimus, an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), sunitinib and other inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF-R), and radiolabeled somatostatin analog therapy.

12. What are the clinical manifestations of gastrinomas?

Gastrinomas secrete excessive gastrin, which stimulates prolific gastric acid secretion. Patients develop severe peptic ulcer disease, often associated with secretory diarrhea. This disorder is also known as the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

13. Do gastrinomas always arise from pancreatic islet cells?

Gastrinomas may arise from the pancreatic islets, but they also can occur in the duodenum and stomach.

14. How is the diagnosis of gastrinoma made?

Gastrinoma is diagnosed by demonstrating a fasting serum gastrin level greater than 1000 pg/mL associated with high gastric acidity (pH ≤ 4.0). For moderately elevated serum gastrin levels of 110 to 1000 pg/mL, a secretin test should be conducted. A gastrin increment of 200 pg/mL or higher 15 minutes after intravenous secretin administration is also diagnostic of this condition. Serum chromogranin A, a nonspecific marker of neuroendocrine tumors, is also significantly elevated in gastrinomas. Patients should discontinue proton pump inhibitor therapy for 1 week before testing for gastrinoma.

15. What is the best way to localize a gastrinoma?

Localization of the tumor may be pursued with various techniques, including CT scan, MRI, endoscopic ultrasonography, octreotide scanning, transhepatic portal venous sampling, and selective arterial secretin infusions with right hepatic vein gastrin measurements.

16. How are gastrinomas managed?

Most benign and some malignant gastrinomas can be cured by surgery. Otherwise, attention should be directed toward reducing gastric acid overproduction. Proton pump inhibitors, in high doses, are the medications of choice for this purpose. Somatostatin analogs (octreotide, Octreotide LAR, lanreotide) are also effective agents. High-dose histamine-2 blockers may be useful but are rarely adequate by themselves. Patients with refractory cases may require total gastrectomy and vagotomy for symptom relief.

17. How do you treat malignant gastrinomas?

Gastrinomas are usually malignant, and therefore antitumor therapy is often necessary. Because liver metastases are common, hepatically directed therapies such as partial resection, hepatic artery embolization, and liver transplantation may be considered. Streptozotocin-doxorubicin combination therapy is the most commonly used cytotoxic regimen for malignant pancreatic endocrine tumors. Everolimus, an inhibitor of mTOR, sunitinib and other inhibitors of VEGF-R, and radiolabeled somatostatin analog therapy are other potential approaches that have shown modest success.

18. What are the characteristics of glucagonomas?

Glucagon antagonizes the effects of insulin in the liver by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Glucagonomas secrete excessive glucagon and thereby cause diabetes mellitus, weight loss, anemia, and a characteristic skin rash, necrolytic migratory erythema. Affected patients also have thromboembolic diathesis. The diagnosis depends on finding an elevated level of serum glucagon (>500 pg/mL). Techniques similar to those used for gastrinomas are useful for localizing these tumors.

19. How are glucagonomas treated?

Treatment options include surgery for localized disease, somatostatin analogs (octreotide, Octreotide LAR, lanreotide) to reduce glucagon secretion, hepatically directed therapies, and chemotherapy regimens similar to those used for gastrinomas. Long-term anticoagulation to reduce the risk of thromboembolic events should also be considered. Finally, zinc supplements and intermittent amino acid infusions may help to reduce the skin rash and to improve the patient’s overall sense of well-being.

20. What are the characteristics of somatostatinomas?

Among its multiple systemic effects, somatostatin inhibits secretion of insulin and pancreatic enzymes, production of gastric acid, and gallbladder contraction. Somatostatinomas secrete excess somatostatin and cause diabetes mellitus, weight loss, steatorrhea, hypochlorhydria, and cholelithiasis. The diagnosis is made by finding a significantly elevated serum somatostatin level.

21. What is the treatment for somatostatinoma?

Surgery is the treatment of choice. When surgery is not possible, the same treatment options as discussed earlier for gastrinomas should be considered.

22. What are the characteristics of VIPomas?

VIPomas cause watery diarrhea, hypokalemia, and achlorhydria (WDHA syndrome). The diagnosis is made by finding a significantly elevated serum VIP level. This is also known as the Verner-Morrison syndrome or pancreatic cholera.

Surgery is the treatment of choice. Somatostatin analogs effectively reduce diarrhea in most patients. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy also may effectively decrease diarrhea and tumor size.

24. Briefly discuss the remaining pancreatic endocrine tumors.

The remaining pancreatic endocrine tumors are rare. CRFomas and ACTHomas lead to the development of Cushing’s syndrome, and GRFomas cause acromegaly. PPomas are initially asymptomatic but may eventually enlarge to produce mass effects without a recognizable hormone hypersecretion syndrome. Localization procedures and treatments are similar to those described earlier for other pancreatic endocrine tumors.

Arnold, R, Simon, B, Wied, M, Treatment of neuroendocrine GEP tumors with somatostatin analogues. review. Digestion. 2000;62(Suppl S1):84–91.

Baudin, E, Gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumors. clinical characterization before therapy. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2007;3:228–238.

Boukhman, MP, Karam, JM, Shaver, J, et al. Localization of insulinomas. Arch Surg. 1999;134:818–822. (discussion 822–823)

Bousquet, C, Lasfargues, C, Chalabi, M, et al. Current scientific rationale for use of somatostatin analogs and mTOR inhibitors in neuroendocrine tumor therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:727–737.

Cryer, PE, Axelrod, L, Grossman, AB, et al, Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders. an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:709–728.

Guettier, J-M, Kam, A, Chang, R, et al, Localization of insulinomas to regions of the pancreas by intraarterial calcium stimulation. the NIH experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:1074–1080.

Jaffe, BM. Current issues in the management of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgery. 1992;111:241–243.

Kar, P, Price, P, Sawers, S, et al. Insulinomas may present with normoglycemia after prolonged fasting but glucose-stimulated hypoglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4733–4736.

Kauhanen, S, Sappanen, M, Minn, H, et al. Fluorine-18-l-dihydroxyphenylalanine (F18DOPA) positron emission tomography as a tool to localize an insulinoma or B-cell hyperplasia in adult patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1237–1244.

Krejs, GJ, Orci, L, Conlon, M, et al, Somatostatinoma syndrome. biochemical, morphologic and clinical features. N Engl J Med 1979;301:283–292.

Leichter, SB. Clinical and metabolic aspects of glucagonoma. Medicine. 1980;59:100–113.

Placzkowski, KA, Vella, A, Thompson, GB, et al. Secular trends in the presentation and management of functioning insulinoma at the Mayo Clinic, 1987–2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1069–1073.

Raymond, E, Dahan, L, Raoul, J-L. Sunitinib for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:501–513.

Ricke, J, Klose, K. Imaging procedures in neuroendocrine tumors. Digestion. 2000;62(Suppl S1):39–44.

Service, FJ. Classification of hypoglycemic disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999;28:501–517.

Service, FJ. Recurrent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia caused by an insulin-secreting insulinoma. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:467–470.

van Schaik, E, van Vliet, EI, Feelders, RA, et al. Improved control of severe hypoglycemia in patients with malignant insulinomas by peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3381–3389.

Wermers, RA, Fatourechi, V, Krols, LK. Clinical spectrum of hyperglucagonemia associated with malignant neuroendocrine tumors. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:1030–1038.

Yao, JC, Shah, MH, Ito, T, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:514–523.