Pancreas

INTRODUCTION

1. Operations on the pancreas are some of the most challenging in abdominal surgery for the following reasons:

The retroperitoneal position of the pancreas renders it relatively inaccessible: the neck, body and tail lie behind the lesser sac while the head is obscured by the greater omentum and transverse colon. Exposure of the pancreas therefore requires a good deal of mobilization.

The retroperitoneal position of the pancreas renders it relatively inaccessible: the neck, body and tail lie behind the lesser sac while the head is obscured by the greater omentum and transverse colon. Exposure of the pancreas therefore requires a good deal of mobilization.

The pancreas is intimately related to major blood vessels, notably the splenic and superior mesenteric veins, which unite to form the portal vein behind its neck. Adherence to the superior mesenteric vessels can make for a difficult dissection in inflammatory or neoplastic disease. The pancreas has a rich arterial supply: the head receives blood from the pancreaticoduodenal arcades and the body and tail from the splenic artery. Its venous drainage to the portal system is by a number of quite large, but thin-walled veins.

The pancreas is intimately related to major blood vessels, notably the splenic and superior mesenteric veins, which unite to form the portal vein behind its neck. Adherence to the superior mesenteric vessels can make for a difficult dissection in inflammatory or neoplastic disease. The pancreas has a rich arterial supply: the head receives blood from the pancreaticoduodenal arcades and the body and tail from the splenic artery. Its venous drainage to the portal system is by a number of quite large, but thin-walled veins.

Shared blood supply and close anatomical relationships necessitate the routine removal of adjacent organs as part of a pancreatic resection: thus the spleen is generally included in a distal pancreatectomy. More importantly, the duodenum and lower bile duct are excised during Whipple’s procedure, necessitating a complex biliary reconstruction.

Shared blood supply and close anatomical relationships necessitate the routine removal of adjacent organs as part of a pancreatic resection: thus the spleen is generally included in a distal pancreatectomy. More importantly, the duodenum and lower bile duct are excised during Whipple’s procedure, necessitating a complex biliary reconstruction.

Resection of the head of the pancreas is followed by anastomosis between the pancreatic stump (a solid organ) and a hollow tube (generally the jejunum). If this anastomosis leaks, powerful digestive enzymes are liberated in active form and can cause severe tissue destruction.

Resection of the head of the pancreas is followed by anastomosis between the pancreatic stump (a solid organ) and a hollow tube (generally the jejunum). If this anastomosis leaks, powerful digestive enzymes are liberated in active form and can cause severe tissue destruction.

Acute and chronic pancreatitis are amongst the most difficult inflammatory conditions to manage anywhere in the body. Likewise, pancreatic cancer is often advanced at diagnosis and may require an extensive resection.

Acute and chronic pancreatitis are amongst the most difficult inflammatory conditions to manage anywhere in the body. Likewise, pancreatic cancer is often advanced at diagnosis and may require an extensive resection.

Diseases of the head of pancreas commonly present with obstructive jaundice which leads to impaired function of many of the body’s systems, notably the kidneys, reticuloendothelial system and coagulation pathways, as well as the liver itself. Thus special precautions are required when undertaking major procedures on such patients.

Diseases of the head of pancreas commonly present with obstructive jaundice which leads to impaired function of many of the body’s systems, notably the kidneys, reticuloendothelial system and coagulation pathways, as well as the liver itself. Thus special precautions are required when undertaking major procedures on such patients.

2. Pancreatic imaging has dramatically improved over the last two decades with the routine use of ultrasonography, spiral computed tomography (CT), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic ultrasound, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).1

Some form of vascular imaging is required prior to pancreatic surgery in order to determine operability and delineate vascular anomalies. Visceral angiography has to a large extent been superseded by CT and MR angiography.

3. Pancreatic endocrine tissue is scattered through the gland in islets described in 1869 by the Berlin physician and anatomist, Paul Langerhans (1847–1888), with a relative preponderance in the body and tail. A major pancreatic resection can impair both endocrine and exocrine function and may cause diabetes and/or steatorrhoea. It is therefore good practice to measure pancreatic function before and after operation, particularly in chronic pancreatitis where there may be pre-existing insufficiency.

4. Pancreatic operations should be covered by appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics such as a cephalosporin.

EXPLORATION OF THE PANCREAS

Access

1. Examination of the pancreas is usually performed as part of a general abdominal exploration.

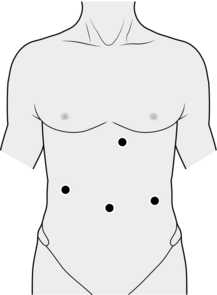

2. If examination of the whole pancreas is the major purpose of the operation, select either a bilateral subcostal incision or a curved transverse incision midway between umbilicus and xiphoid and convex upwards.

3. Adequate inspection and palpation of the whole pancreas requires both mobilization of the duodenum and entry into the lesser sac.

Assess

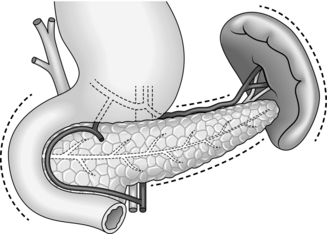

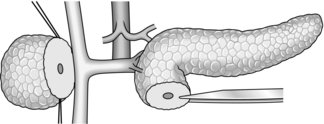

1. Mobilize the duodenal loop and pancreatic head by Kocher’s manoeuvre (Fig. 16.1). Gently clear the omentum from the anterior aspect of the head of pancreas, which can now be directly inspected and palpated between finger and thumb.

2. Expose the body and tail of the pancreas through the lesser sac, which can be entered through the greater or lesser omentum. Separate the congenital adhesions between the stomach and the pancreas. If necessary, divide the peritoneum along the superior border of the pancreas, so that you can insinuate a finger beneath the gland.

3. The inferior border of the pancreas can also be mobilized by dividing the overlying peritoneum; take care not to injure the superior or inferior mesenteric veins. Trace the middle colic vein downwards to find the superior mesenteric vein.

4. Lying at the splenic hilum, the tail of pancreas is the least accessible part of the gland. It can usually be approached by dividing the greater omentum and retracting the stomach upwards. You may need to divide several short gastric arteries and the attachments of the splenic flexure of the colon from the spleen. If necessary, be willing to divide the peritoneum lateral to the spleen and lift the spleen and tail of pancreas forwards into the wound.

5. Learn to recognize the firm, nodular consistency of normal pancreas by palpating the gland during all upper abdominal operations. You should then be able to differentiate the hard sclerotic gland of chronic pancreatitis or a localized tumour. The pancreatic duct is not palpable unless it is dilated.

6. If you feel a mass in the region of the ampulla, it may assist diagnosis to open the duodenum and directly visualize the pancreatic papilla. Confirm suspected carcinoma at this site by removing a suitable biopsy for immediate frozen-section histology, if endoscopic biopsy has not already provided the diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Fayad LM, Kowalski T, Mitchell DG. MR cholangiography: evaluation of common pancreatic diseases. Radiol Clin North Am 2003;41:97–114.

PANCREATIC BIOPSY

Appraise

1. No method of biopsying the pancreas is devoid of risk, yet a positive tissue diagnosis is particularly important for the proper management of suspected malignant disease.

2. Cancer in the head of the pancreas usually obstructs the pancreatic duct, leading to chronic pancreatitis in the upstream gland. At operation it can be difficult or even impossible to distinguish the induration of obstructive pancreatopathy from that of malignant infiltration, which may lead to sampling error. Likewise, on pancreatic imaging there is often no sharp distinction between tumour and adjacent pancreatitis.

3. Percutaneous biopsy of the pancreas can be carried out under ultrasound or CT scan guidance by directly inserting a fine needle for cytology, or wider-bore needle for histology, into the mass. In expert hands this is quite a sensitive technique, although more than one pass of the needle may be required to obtain a positive answer. Although percutaneous biopsy of the pancreas is a relatively safe and sensitive technique, as a rule limit it to patients with unresectable tumours or those patients in whom operative treatment is not indicated.1

4. At ERCP pure pancreatic juice may be obtained or brushings can be taken from strictures of the bile duct or pancreatic duct. Cytological examination of this material may reveal malignant cells. When pancreatic cancer invades the duodenum, it can be directly biopsied through the endoscope. Endoscopic ultrasound has been increasingly used to guide biopsy of pancreatic lesions, as well as providing valuble information about relationship to major vascular structures.2

5. At laparotomy the safest method of confirming the diagnosis of cancer is to sample a site of possible metastasis, usually a liver nodule, peritoneal deposit or lymph node adjacent to the pancreas (see Chapter 17 for the technique of liver biopsy). If there are no obvious metastases, do not hesitate to biopsy the primary pancreatic tumour itself.

6. The usual indication for pancreatic biopsy is to confirm carcinoma in a patient whose tumour is deemed irresectable, since in a resectable case the specimen itself provides ample histological material. Because of the risk of sampling error you must obtain pathological confirmation of carcinoma before closing the abdomen, and this need may govern the choice between fine-needle aspiration biopsy and the use of a Tru-cut needle. In many hospitals it is easier to obtain urgent frozen-section histology, as from a Tru-cut specimen, than an urgent cytological opinion.

Action

1. Using a fine (18–20G) needle and a 20-ml syringe, aspirate the site of the lesion. Apply strong suction while advancing and withdrawing the needle within the lesion, then release the suction and remove the needle and syringe. Eject the material in the needle track on to a glass slide and make a smear for cytological examination.

2. If the surface of the pancreas is diseased, perform a ‘shave’ biopsy with a scalpel. Remember the possibility that an inflammatory ‘halo’ may surround the actual neoplastic tissue.

3. You can obtain a core of tissue for histological examination using a Tru-cut needle. If the lesion is in the head of the pancreas you can approach it transduodenally, avoiding the risk of pancreatic fistulae, or insert the needle directly into the pancreas.

4. If the above techniques are inadequate and a biopsy is essential, incise the gland directly over the lesion and obtain a small piece of tissue. However, it may be better to carry out a formal partial pancreatectomy under these circumstances.

5. The complications of biopsy include acute pancreatitis and pancreatic fistula. If pancreatic juice escapes from the site of incision or the needle puncture, consider pancreatectomy or Roux-en-Y drainage of this area.

LAPAROTOMY FOR NECROTIZING PANCREATITIS

Appraise

1. There is absolutely no role for diagnostic laparotomy in patients with acute pancreatitis, given the widespread availability of abdominal CT. Despite this, you may be confronted occasionally by acute pancreatitis during a laparotomy for other suspected pathologies such as small-bowel infarction and leaking abdominal aneurysm.

2. Avoid laparotomy in the first week of acute pancreatitis, as it is too early for a safe, effective debridement and formal resection carries a formidable mortality rate. Laparotomy can often be delayed for several weeks to allow the necrotic tissue to mature, and the vast majority of infective collections can be managed by aggressive radiological drainage. Patients with proven severe gallstone pancreatitis may, however, benefit from early ERCP and stone extraction if ductal calculi are suspected, as this may lower both morbidity and mortality.1

3. Laparotomy and debridement for patients with established necrotizing pancreatitis is now reserved primarily for those with infected necrosis.2 Determine the presence of infection preoperatively by percutaneous radiological fine-needle aspiration. For necrosis confined predominately to the left of the neck of pancreas, open necrosectomy has almost completely been superseded by aggressive radiological drainage and video assisted percutaneous necrosectomy in specialist units. Percutaneous radiological drains are inserted under local anaesthetic in the plane between the spleen and splenic flexure of the colon. The tract is subsequently dilated to permit passage of a nephroresectoscope. The necrotic tissue can then be resected using the endoscope and irrigation catheters inserted. Initial publications suggest a reduction in mortality and morbidity with this minimally invasive approach.3

4. If you detect gallstones it is wise to carry out a cholecystectomy after the patient has recovered from pancreatitis but before discharge so as to prevent another acute attack (see Chapter 15). Prior to operation, have the bile duct imaged using either MRCP or ERCP to avoid leaving occult ductal calculi.

Prepare

1. On admission, or following a diagnostic laparotomy, it is helpful to assess the severity of acute pancreatitis using the Ranson or Imrie scoring systems and/or serial measurements of C-reactive protein and white cell count.

2. Hypovolaemia is a consistent feature of acute pancreatitis and may be profound. Make sure that fluid depletion has been fully corrected by intravenous administration of colloid and crystalloid solutions before embarking on the operation. Monitor central venous pressure and urine output during resuscitation in the elderly or those with severe fluid loss.

3. Look for and treat early complications such as hypoxaemia, hypocalcaemia and incipient renal failure. Give prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Access

1. If the cause of peritonitis is uncertain, the patient is likely to have a midline incision performed for abdominal exploration. If necessary, extend the incision upwards to permit examination of the biliary apparatus and pancreas.

2. When operating for confirmed pancreatitis, use a transverse incision.

Assess

1. Bloodstained free fluid is usually present in the abdominal cavity in acute pancreatitis. Whitish plaques of fat necrosis are visible on serosal surfaces, especially in the region of the pancreas.

2. Lift up the greater omentum and transverse colon. There is oedema and blackish discoloration of the retroperitoneal tissues. The pancreas itself is swollen and may be haemorrhagic or even necrotic.

3. Examine the gallbladder and, if possible, the bile duct to determine if these organs are diseased. A more thorough examination is required if the patient has obstructive jaundice.

4. In a case of infected pancreatic necrosis, extensively explore the retroperitoneal tissues to carry out a full assessment.

Action

At laparotomy

1. Once you have made the diagnosis, do nothing unless there is a definite indication. Attempts at debridement of the pancreas at this stage can be disastrous. Formal exploration of the pancreas is usually unnecessary to obtain a diagnosis and may be meddlesome.

2. The management of coincidental gallstones is controversial, so be prepared to seek senior advice. In oedematous (mild) pancreatitis it is correct to carry out cholecystectomy with operative cholangiography and proceed to exploration of the duct and even transduodenal sphincteroplasty, if necessary (see Chapter 15). In haemorrhagic, severe pancreatitis, extensive ductal exploration and duodenotomy are best avoided. If ductal stones are present, remove them gently if possible and leave a T-tube to drain the duct.

3. It is unusual to encounter loculated fluid or pus during the first week of an attack of acute pancreatitis, but drain any such collection to the exterior.

4. Wound dehiscence is common following laparotomy for acute pancreatitis. Take extra care in closing the linea alba or rectus sheath and consider inserting tension sutures.

For infected pancreatic necrosis

1. Enter the lesser sac by dividing the greater omentum. In severe pancreatitis this will expose a large cavity containing pus and necrotic debris. Although the pancreas itself can undergo haemorrhagic infarction in a severe case of pancreatitis, more often the gland is viable and there is peripancreatic necrosis affecting the retroperitoneal fat.

2. Digitally explore the necrotic cavity and remove all dead tissue. The cavity may ramify extensively: be prepared to explore upwards to the diaphragm, downwards behind the left or right colon to the pelvis, backwards to the perirenal areas and forwards into the transverse mesocolon and the root of the small bowel mesentery. Where possible, avoid sharp dissection and use your fingers to separate the solid necrotic material. A blunt-tipped sucker, used gently, provides a good method of atraumatic dissection. Send samples of fluid and necrotic material for bacteriological examination. The main risk is of bleeding, so be gentle but thorough.

3. Check the viability of the small and large intestine. The right colon in particular can become ischaemic following thrombosis of its blood supply. In these circumstances proceed to right hemicolectomy, but do not restore intestinal continuity. Bring out the terminal ileum as an end ileostomy (Chapter 11) and the transverse or descending colon as a mucous fistula, using separate trephine incisions for each stoma. Placement of a gastrostomy avoids long-term nasogastric intubation and insertion of a jejunostomy tube aids early enteric feeding.4

4. Irrigate the retroperitoneal cavity thoroughly with warm saline and secure haemostasis. You must now choose between closing the abdomen with generous drainage and leaving it open as a ‘laparostomy’. Each technique has its advocates. The closed technique is easier to manage with regard to nursing care, but up to one-third of patients require one or more repeat laparotomies for further debridement. The open technique allows inspection of the abdominal contents on a daily basis with ready drainage of further collections, but at the expense of a higher incidence of postoperative bleeding and intestinal fistula. For this reason laparostomy should be reserved for the most severe cases and the closed drainage technique used when necrosis is less extensive.

5. In the closed technique it is vital to ensure adequate drainage of the retroperitoneal cavity and lesser sac. Place four wide-bore drains, siting two as far posteriorly as possible, one on each side. If the necrotizing process is limited to the lesser sac, it is helpful to ‘compartmentalize’ the abdomen by suturing the greater omentum to the peritoneum along the lower border of the transverse incision. Postoperatively, the lesser sac can then be irrigated in isolation from the remaining abdominal viscera. Take care closing the abdomen because of the risk of subsequent wound dehiscence. Insert deep tension sutures in severe cases.

6. In the open technique make no attempt to suture the abdominal wall. One or two drains may be placed in the depths of the cavity and brought out through stab incisions. Cover the exposed viscera with several packs wrung out in saline. Consider placing a large piece of adherent plastic sheeting over the entire wound to prevent leakage of fluid. Surprisingly, evisceration is seldom a problem.

Aftercare

1. Continue standard supportive measures for acute pancreatitis, with intravenous fluids and nasogastric suction as required. Patients with a severe attack will require total parenteral nutrition. Antibiotic therapy is needed to manage septic complications, the choice of agent being tailored to the organism cultured. Recent evidence suggests that, in cases of severe pancreatitis, early prophylactic antibiotics decrease the incidence of septic complications and there may be a corresponding decrease in mortality rate.5

2. All patients with severe acute pancreatitis should be managed in an intensive therapy unit. Ultrasound and CT scans may be used to detect the development of complications, notably pseudocyst, bleeding and infected pancreatic necrosis.

3. Following a closed drainage procedure for necrotizing pancreatitis, institute saline lavage down two of the four drains, using the other two for egress of the fluid. Commence lavage with warm isotonic fluid either at the end of the operation or after overnight recovery, allowing the peritoneum to ‘seal’. Infuse between 50 and 200 ml/hour, depending upon the size of the cavity and the degree of contamination. Continue lavage at least until the effluent becomes clean. Monitor the serum albumin level, because prolonged lavage will exacerbate protein depletion. Use clinical judgement and weekly CT scans to assess progress and the necessity or otherwise for repeat laparotomy and debridement.

4. Following laparostomy, inspect the abdominal cavity. Nearly all these patients will require mechanical ventilation in an intensive therapy unit, and the packs can usually be changed in this setting under intravenous sedation without the need to take the patient back to the operating theatre. Remove the packs and examine the abdominal viscera. Gently insinuate your hand into the cavity, drain any pus and tease out any further necrotic tissue. Wash out the cavity and place fresh packs. If the patient’s condition improves, consider secondary closure of the abdominal wall at a later date.

Complications

1. Infected pancreatic necrosis is a difficult and dangerous condition. The mortality rate is at least 20–30% in most published series. A successful outcome requires good surgical and nursing care which often needs to be continued for several weeks. Supportive measures include intravenous fluids, parenteral nutrition and antibiotics as required.

2. There are many potential complications, and their management can be summarized as follows:

Respiratory failure/adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Continue assisted respiration under the supervision of an experienced anaesthetist, and consider tracheostomy after 10–14 days of endotracheal intubation (see Chapter 2).

Respiratory failure/adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Continue assisted respiration under the supervision of an experienced anaesthetist, and consider tracheostomy after 10–14 days of endotracheal intubation (see Chapter 2).

Renal failure. Haemofiltration or haemodialysis is required unless the infracolic compartment of the abdomen can be used for peritoneal dialysis. Dopamine and dobutamine may be used to improve renal blood flow.

Renal failure. Haemofiltration or haemodialysis is required unless the infracolic compartment of the abdomen can be used for peritoneal dialysis. Dopamine and dobutamine may be used to improve renal blood flow.

Myocardial failure. Pressor support may be required to maintain an adequate blood pressure and peripheral circulation.

Myocardial failure. Pressor support may be required to maintain an adequate blood pressure and peripheral circulation.

Continuing sepsis. This is the single most important factor underlying multiple organ failure. Persistent high fever and leucocytosis indicate active infection. Remember the possibility of septicaemia from a contaminated central venous line: obtain blood cultures and consider changing the line. Repeat the chest X-ray to look for a focus of infection. Perform ultrasound, CT or isotope scans to image the abdominal cavity, and consider whether percutaneous drainage or repeat laparotomy is needed to deal with further collections.

Continuing sepsis. This is the single most important factor underlying multiple organ failure. Persistent high fever and leucocytosis indicate active infection. Remember the possibility of septicaemia from a contaminated central venous line: obtain blood cultures and consider changing the line. Repeat the chest X-ray to look for a focus of infection. Perform ultrasound, CT or isotope scans to image the abdominal cavity, and consider whether percutaneous drainage or repeat laparotomy is needed to deal with further collections.

Intestinal failure. Prolonged ileus is common in patients with abdominal sepsis, especially those on a ventilator. Remember the possibility of colonic or small-bowel ischaemia, which may require repeat laparotomy. Very occasionally prolonged duodenal ileus necessitates a gastroenterostomy. These patients are prone to peptic stress ulceration: institute prophylaxis with topical agents such as sucralfate or intravenously with H2-receptor antagonists or proton-pump inhibitors.

Intestinal failure. Prolonged ileus is common in patients with abdominal sepsis, especially those on a ventilator. Remember the possibility of colonic or small-bowel ischaemia, which may require repeat laparotomy. Very occasionally prolonged duodenal ileus necessitates a gastroenterostomy. These patients are prone to peptic stress ulceration: institute prophylaxis with topical agents such as sucralfate or intravenously with H2-receptor antagonists or proton-pump inhibitors.

Haemorrhage. Bleeding follows arterial or venous erosion in the wall of the infected cavity and blood may escape into the gut, into the abdominal cavity or via the drains. Resuscitate the patient and, if there is gastrointestinal haemorrhage, consider endoscopy to look for erosive gastritis (see Chapter 10). If there is evidence of intra-abdominal bleeding the patient should have a CT scan with vascular reconstruction. In most instances this reveals the site of bleeding and identifies the feeding vessel. This can then be treated by visceral angiography and transcatheter embolization. If radiology is unsuccessful then a laparotomy may be required, with suture of the bleeding vessel and occasionally formal resection. Such operative procedures carry a high morbidity and mortality.

Haemorrhage. Bleeding follows arterial or venous erosion in the wall of the infected cavity and blood may escape into the gut, into the abdominal cavity or via the drains. Resuscitate the patient and, if there is gastrointestinal haemorrhage, consider endoscopy to look for erosive gastritis (see Chapter 10). If there is evidence of intra-abdominal bleeding the patient should have a CT scan with vascular reconstruction. In most instances this reveals the site of bleeding and identifies the feeding vessel. This can then be treated by visceral angiography and transcatheter embolization. If radiology is unsuccessful then a laparotomy may be required, with suture of the bleeding vessel and occasionally formal resection. Such operative procedures carry a high morbidity and mortality.

Pancreatic fistula. Survivors may develop a pancreatic fistula from the abscess cavity along a drain track to the skin. Most of these fistulas heal spontaneously with the passage of time and can simply be managed in the interim by collection into a stoma bag. Manage an intestinal fistula or mixed fistula along standard lines (see Chapter 11).

Pancreatic fistula. Survivors may develop a pancreatic fistula from the abscess cavity along a drain track to the skin. Most of these fistulas heal spontaneously with the passage of time and can simply be managed in the interim by collection into a stoma bag. Manage an intestinal fistula or mixed fistula along standard lines (see Chapter 11).

REFERENCES

1. Fogel EL, Sherman S. Acute biliary pancreatitis: when should the endoscopist intervene. Gastroenterology 2003;125:229–35.

2. Werner J, Uhl W, Hartwig W, et al. Modern phase-specific management of acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis 2003;21:38–45.

3. Carter CR, McKay CJ, Imrie CW. Percutaneous necrosectomy and sinus tract endoscopy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis: an initial experience. Ann Surg 2000;232:175–80.

4. Al-Omran M, Groof A, Wilke D. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1): CD002837.

5. Bassi C, Larvin M, Villatoro E. Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4): CD002941.

DRAINAGE OF PANCREATIC CYSTS

Appraise

1. True cysts are congenital or neoplastic and are rare. Cysts complicating acute or chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic trauma are ‘false’ pseudocysts, in that they have no epithelial lining. Both types are best diagnosed by ultrasound and CT scanning of the upper abdomen.

2. Fluid collections around the pancreas are common following acute pancreatitis, but most resolve spontaneously. Drainage is required for an expanding mass, which often causes pain, for vomiting, jaundice or for a mass that fails to resolve or becomes infected. Within 4–5 weeks of the acute attack, the cyst wall is unlikely to be sufficiently mature to take sutures, and external drainage is required. Thereafter, internal drainage becomes feasible, either cystgastrostomy or cystjejunostomy Roux-en-Y. Reserve cystgastrostomy for moderate-sized cysts that are closely applied to the back of the stomach on imaging. Endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques are increasingly employed to avoid open operation for internal cyst drainage.

3. Percutaneous aspiration of pancreatic pseudocysts is becoming increasingly popular. The procedure is carried out under ultrasound or CT control. A pigtail catheter can be inserted for external drainage, or a percutaneous transgastric approach can be used to position a stent in the cystgastrostomy position.1 Percutaneous needle drainage is suitable for small cysts discovered in the early weeks after an attack of acute pancreatitis; surgical drainage is more appropriate for large, mature or recurrent cysts and for those that communicate with the pancreatic duct.

4. Sometimes an encysted collection of blood and/or pancreatic fluid may follow blunt abdominal trauma. Traumatic cysts are prone to complications and require early drainage, usually to the exterior.

5. Pseudocysts developing in association with chronic pancreatitis are generally contained within the pancreatic capsule and frequently communicate with the main ductal system. They may develop insidiously with gradual expansion of the pancreas, sometimes at multiple sites, or rapidly after an attack of acute-on-chronic pancreatitis, in which case they contain necrotic material. Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography is a useful investigation as it allows drainage of the dilated pancreatic duct, but may, potentially, introduce infection into the cyst cavity: give prophylactic antibiotic cover. Smaller cysts can be resected together with diseased pancreas or drained into the duct and thence to a Roux loop of jejunum. Treat larger cysts by cystenterostomy unless a preoperative angiogram shows an arterial pseudo-aneurysm in the wall, in which case resection may be safer.

6. Never assume that a cystic mass in or adjacent to the pancreas is an inflammatory pseudocyst unless there is clear evidence of acute pancreatitis (for example recent pain and hyperamylasaemia) or a history and imaging consistent with chronic pancreatitis. Cystic neoplasms include serous and mucinous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma and cystic endocrine tumour. Always obtain a biopsy of the cyst wall at operation, and arrange frozen-section examination if there is any suspicion of neoplasia.2 Resect neoplastic cysts if possible.

7. Endoscopic internal drainage of a pseudocyst under endoscopic ultrasound guidance is gaining in popularity. With a diathermy wire passed down the operating channel of an endoscope, the endoscopist creates an opening from the cyst into the stomach or duodenum and usually passes several stents to maintain patency.3 It is even possible to drain a communicating pseudocyst into the duct via a nasopancreatic tube or short pancreatic stent passed per endoscope.

Assess

1. After an acute attack of pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma an encysted collection of fluid may be entered on approaching the pancreas. This type of collection is usually best drained to the exterior. The resultant pancreatic fistula does not cause skin excoriation, since the pancreatic enzymes are not activated, and it will nearly always close spontaneously. If a large cyst is palpable within the lesser sac, try to determine whether the posterior wall of the stomach is adherent to the front of the cyst, in which case cystgastrostomy may be appropriate. If not, internal drainage into a Roux loop of jejunum is a satisfactory method of dealing with a mature cyst.

2. During laparotomy for chronic pancreatitis plan your approach according to the operative findings, supplemented by a knowledge of pancreatic ductal anatomy obtained from ERCP or MRCP. A cyst in the head of the pancreas can sometimes be marsupialized into the duodenum. Elsewhere in the gland, cystjejunostomy Roux-en-Y is the best option unless complete resection can be safely achieved.

3. Try and create a good-sized fistula between the cyst and the viscus chosen for internal drainage.

Action

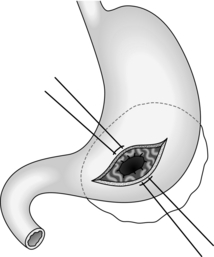

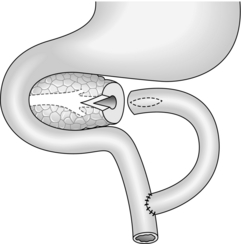

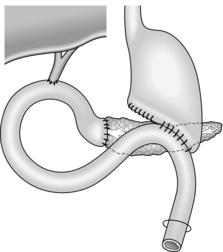

Cystgastrostomy (Fig. 16.2)

1. This is only indicated for effusions into the lesser sac that have been present for long enough to have developed a fibrous wall. The stoma will probably close once the cavity has collapsed following drainage.

2. After packing off the stomach, make a longitudinal incision through the anterior gastric wall fairly close to the greater curvature and opposite the incisura angularis. Suck out the gastric contents.

3. Now incise the posterior gastric wall for a short distance opposite the anterior gastrotomy. If the cyst is difficult to palpate, a 19 Gauge needle on a 10-ml syringe is often used to localize the cyst. Deepen the incision and enter the cyst, obtaining samples of the fluid for culture and chemical analysis. Evacuate the contents of the cyst and gently break down any loculi with your finger.

4. Insert a running polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) suture round the margins of the posterior gastrotomy, ensuring a stoma at least 4 cm in diameter. Close the anterior gastrotomy in two layers and close the abdomen with drainage.

Cystduodenostomy

1. Reserve this procedure for a small cyst in the head of pancreas close to the duodenal loop.

2. Make a longitudinal duodenotomy opposite the cyst. Insert a needle into the cyst: aspiration of bile warns you that the bile duct is nearby and you should not proceed.

3. If the aspirate is clear, leave the needle in place and incise the duodenal wall to enter the cyst. Suture the margins of the opening as above. Close the duodenum in two layers, taking care not to narrow its lumen. Close the abdomen with drainage.

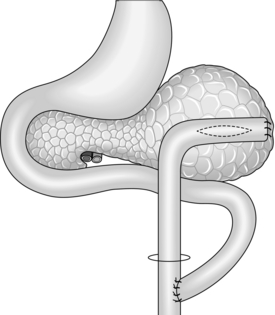

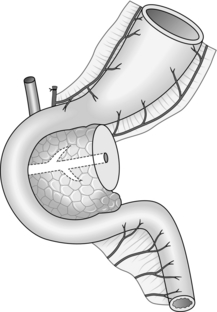

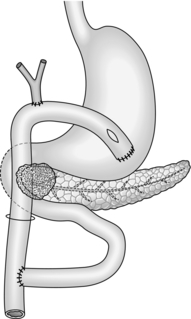

Cystjejunostomy (Fig.16.3)

1. This technique is applicable to all types of cyst with walls thick enough for suturing. It is the most likely method to obtain dependent drainage and avoid the potential problem of food debris contaminating the pseudocyst cavity.

2. Mobilize the pancreas. Now incise the anterior wall of the cyst, sample and drain its contents and explore its recesses for any obvious ductal communication.

3. Create a Roux loop of jejunum (Chapter 11) and close the end. Approximate the upper end of the Roux loop to the front of the cyst without tension. Create a generous side-to-side anastomosis between the opening into the cyst and a longitudinal jejunotomy. Use one or two layers of suture according to the thickness of the cyst wall, but use polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) for the inner layer.

4. Restore intestinal continuity by jejunojejunostomy at the base of the Roux loop. Drain the abdomen through a stab incision as above.

Complications

1. Decompression of a pseudocyst into the gut may be followed by haemorrhage if there was a pre-existing pseudo-aneurysm and angiography, whether derived from CT, MRI or visceral angiography, should always be undertaken before drainage of a chronic cyst. If bleeding occurs the patient requires a CT scan, with an emphasis on the arterial phase, to determine the site of origin, proceeding to an angiogram and transcatheter embolization. If this fails, re-operation is required, sometimes with formal resection.

2. Pancreatic fistula is seldom troublesome, because the enzyme content of pancreatic juice is low in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Treat a gastric or intestinal fistula along standard lines.

REFERENCES

1. Vidyarthi G, Steinberg SE. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Clin North Am 2001;81:405–10.

2. Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, et al. Cystic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann Surg 2004;239:651–9.

3. Beckingham IJ, Krige JE, Bornman PC, et al. Long term outcome of endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:71–4.

DRAINAGE OF THE PANCREATIC DUCT

Appraise

1. Ductal drainage is preferable to resection for the relief of pain in chronic pancreatitis, since it preserves the remaining functioning tissue. However, only an anastomosis between the pancreatic duct and adjacent viscus that is several millimetres in diameter is likely to remain patent. Therefore do not ordinarily undertake a drainage operation unless the duct is two to three times its normal diameter.

2. The operation of choice is longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy, which creates a long side-to-side anastomosis between the incised duct and a Roux loop of jejunum. Often this may be combined with a ‘coring’ out of the head of the pancreas, a so-called ‘Frey modification’. An anastomosis between the amputated body of pancreas and a Roux loop is less likely to stay open unless the duct is grossly dilated at the site of transection, in which case it should probably be opened up in the proximal gland. Sometimes it is reasonable to combine conservative distal resection with a limited longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy.

3. Formerly popular for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis, sphincteroplasty has in fact little to offer. It is reasonable to consider biliary sphincteroplasty (Chapter 15), followed by a similar procedure to widen the orifice of the pancreatic duct, when there is moderate dilatation of the whole duct tapering to a stricture at its orifice, but this is an uncommon situation in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatic sphincteroplasty may be indicated for patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis or chronic abdominal pain and stenosis in the terminal pancreatic duct. In pancreas divisum, accessory pancreatic sphincteroplasty is sometimes helpful.

4. Drainage of an obstructed distended duct into the back of the stomach (pancreaticogastrostomy) is quite a simple technique that may bring worthwhile relief of pain from irresectable carcinoma of the head of pancreas.

5. Techniques for draining normal-calibre and dilated pancreatic ducts after proximal pancreatectomy (Whipple resection) are considered at the end of this chapter.

Prepare

1. Do not operate on patients with chronic pancreatitis unless you have some experience of this disease and are capable of carrying out pancreatectomy.

2. Ensure that appropriate preoperative imaging and pancreatic function tests have been undertaken.

3. Arrange for cross-matched blood to be available and give prophylactic antibiotics perioperatively.

Assess

1. Expose the pancreas carefully but completely and examine it thoroughly. Is the gland indurated throughout, or is the disease partly localized? Can you feel the pancreatic duct as a soft dilated tube in the body of the gland? Are there any associated cysts? If there is suspicion of carcinoma, obtain a biopsy.

2. Look for evidence of gallstones, which are quite commonly associated with chronic pancreatitis. The bile duct may be slightly dilated, with a thickened, opaque wall. Examine the stomach and duodenum for peptic ulcer disease. Exclude cirrhosis of the liver, portal hypertension and splenomegaly. Perform liver biopsy if the patient is an alcoholic.

Action

Pancreatic sphincteroplasty

1. Expose the papilla by a transduodenal approach and carry out biliary sphincteroplasty.

2. Look for the orifice of the major pancreatic duct on the lower lip of the papilla. Magnifying spectacles may be helpful. Pass a soft umbilical catheter (4–6F) and obtain a retrograde pancreatogram if ERCP or MRCP were inadequate. If you cannot locate the orifice, ask the anaesthetist to give an intravenous injection of secretin (1 unit/kg) and look for the flow of pancreatic juice within 30–60 seconds.

3. Divide the common septum between the terminal portions of the bile duct and pancreatic duct for a distance of about 10 mm. Obtain a tiny biopsy if the septum appears scarred. Facilitate the septotomy by placing fine (5/0) sutures on either side of the proposed line of incision, tying them and dividing the septum between them, using straight iris scissors.

4. Suture the mucosa of the pancreatic duct to that of the bile duct using 5/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures.

5. A similar technique should be used for accessory sphincteroplasty, but here it is often necessary to give secretin to identify the tiny ductal orifice.

6. Close the duodenum and leave a drain in the subhepatic space as for biliary sphincteroplasty.

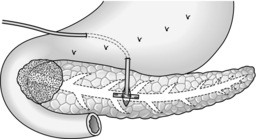

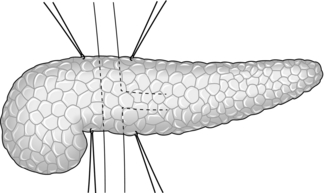

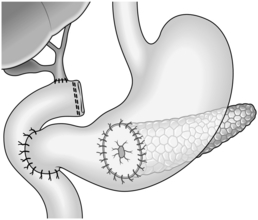

Longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (Fig. 16.4)

1. Expose the body, neck and part of the head of pancreas through the lesser sac. It is usually not necessary to mobilize the gland completely.

2. Incise the front of the pancreas between stay sutures at a convenient place in the body of the gland. If the duct is clearly dilated, make the incision in the long axis of the gland. If not, either attempt to localize the duct by aspiration, using a small needle and a 10-ml syringe, or make a small exploratory incision across the axis. Intra-operative ultrasound can be helpful in identifying an impalpable duct. If localizing the duct using an aspirating needle, it is possible to cut down along the plane of the needle to open up the duct.

3. On entering a dilated ductal system, aspirate the pale, greyish pancreatic juice. Extend the incision in each direction, using scalpel or pointed scissors, and under-run any major bleeding vessel. Ensure that the gastroduodenal artery is properly controlled where it is divided in the neck of the gland. Open the duct widely from head to tail. Remove all calculi and try to open any cysts into the main duct.

4. Select a Roux loop of jejunum and close its end. Bring the loop through a mesocolic window so that it lies comfortably along the entire pancreas. Insert interrupted Vicryl sutures to approximate the fibrotic ‘capsule’ of the pancreas and the seromuscular layers of the jejunum. Now make a long jejunotomy to match the incision in the pancreatic duct and place a running all-coats suture between the two, using 3/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). The ductal lining is tough and takes sutures quite well. Finish with an anterior seromuscular layer.

5. Restore intestinal continuity by end-to-side jejunojejunostomy. Close the abdomen with drainage of the pancreas.

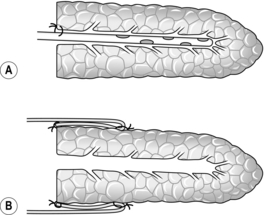

Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (Fig. 16.5)

1. Reserve this procedure for draining a dilated duct in the neck or proximal body of pancreas after distal resection. It may be sensible to open up the duct at the site of transection by incising for a few centimetres through its anterior wall and the overlying pancreas.

2. Fashion a retrocolic Roux loop of jejunum as above and close the end. Make a small subterminal jejunotomy to match the diameter of the duct and insert an all-coats suture, using fine non-absorbable stitches. Tack the peripheral pancreatic substance to the seromuscular layer of jejunum with a second layer of similar sutures.

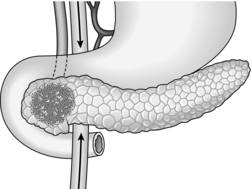

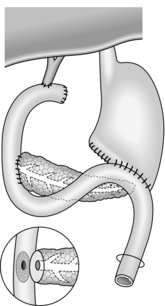

Intubated pancreaticogastrostomy (Fig. 16.6)

1. Examine the body of pancreas for the tell-tale sensation of a dilated duct. Needling the duct or intra-operative ultrasound may be helpful.

2. Make a short vertical incision across the body of pancreas and deepen this until you enter the duct. Insert a T-tube into the duct; suture the gland around the entry of the tube. Make tiny posterior and anterior gastrotomies several centimetres apart. Bring the tube through each wall of the stomach and thence by a stab incision to the exterior. Make sure there are two or three holes in the tube within its intragastric course, and tighten a purse-string suture around the anterior gastrotomy. By traction on the tube, draw the stomach down on to the front of the pancreas, and approximate the two organs with a few tacking sutures.

3. Postoperatively, the T-tube may drain the stomach in preference to the nasogastric tube, but it can usually be clamped with safety after flatus has been passed per rectum.

Complications

1. These are uncommon, but reactive haemorrhage and pancreatic fistula are theoretical risks, as after a cyst drainage procedure (see above).

2. Acute pancreatitis should not follow a sphincteroplasty unless the ductal orifice has been inadvertently occluded.

3. A transient rise in serum amylase following manipulation of the pancreas is of little importance.

LAPAROTOMY AND BYPASS FOR PANCREATIC CANCER

Appraise

1. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is both common and difficult to treat. Its cause is largely unknown. Most tumours are irresectable by the time they are diagnosed, and this is particularly so for cancers of the body and tail of pancreas, where early symptoms are scarce and non-specific. When the tumour is within the head of pancreas, the patient may present with obstructive jaundice while the tumour is still relatively small and localized.

2. Some patients with cancer of the head of pancreas require laparotomy to confirm the diagnosis, determine the potential resectability of the tumour and allow a choice to be made between resection and bypass. Despite the scale of the operation required, carry out resection for potentially curable tumours in those of reasonable general health, since this policy offers the only chance of cure. Less aggressive cancers such as neuroendocrine tumour or cholangiocarcinoma may be difficult or impossible to differentiate from pancreatic cancer on either preoperative or operative assessment, and the same can hold true for chronic pancreatitis.

3. Staging laparoscopy in combination with laparoscopic ultrasound may allow detection of peritoneal deposits, small liver metastases and even portal venous invasion, but the number of patients in whom this will add extra information to that obtained from conventional imaging is controversial. Some authors claim that laparoscopic examination excludes an extra 30% of patients from curative resection. Most series suggest that 14% of patients can be spared an unnecessary laparotomy,1 and if one considers that laparoscopy may in fact provide the opportunity to institute palliative bypass then this technique of staging becomes attractive.

4. Most patients with cancer of the body or tail of pancreas do not require laparotomy because the tumour either metastasizes or encases the superior mesenteric vessels at an early stage and is therefore seldom resectable.2 Moreover, jaundice and duodenal obstruction occur late, if at all. Thus optimal management comprises obtaining a tissue diagnosis by means of guided percutaneous needle biopsy, confirming the irresectability of the tumour by CT scan and considering non-operative measures such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, especially for younger patients and those with troublesome back pain. However, if imaging leaves you in any doubt about the nature or resectability of the tumour, perform laparotomy.

5. Preoperative investigation of a patient with obstructive jaundice starts with liver function tests and ultrasound scan to exclude hepatocellular disease and confirm dilatation of the biliary tree consistent with a ‘surgical’ cause of obstruction. Ultrasound and CT scan may show gallstone disease, a pancreatic or peri-ampullary mass, nodal or hepatic metastases and major vascular involvement. PTC and ERCP are invaluable for showing the level and the nature of bile duct stricture, but one or other test will generally suffice. PTC gives better visualization of the proximal biliary tree, which is useful for a high stricture, whereas ERCP can provide an additional pancreatogram, which is useful to confirm pancreatic cancer or chronic pancreatitis. If combined with endoscopic ultrasound, this can visualize the adjacent vascular structures and aid in the assessment of operability.3 Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration can provide a cytological diagnosis without risking tumour seeding outside the pancreas. If preoperative jaundice is not deep and stenting not required, then non-invasive imaging with MR or spiral CT may be sufficient. Delineation of the adjacent venous and arterial anatomy is important both in determining operability and in identification of anatomical anomalies. This can usually be achieved non-invasively using three-dimensional reconstructions of CT,3 but may require formal visceral angiography. Preoperative percutaneous biopsy is unnecessary in patients who are proceeding to laparotomy.

6. It is debatable whether non-operative stenting or surgical bypass is the better option for irresectable cancer of the pancreatic head. Stenting can be achieved by either the percutaneous transhepatic route or the endoscopic transpapillary route depending on available local expertise. In expert hands the two procedures have similar morbidity and mortality rates equivalent to those of surgical bypass. The recent introduction of expandable metal stents seems likely to reduce the problem of stent clogging, which leads to cholangitis and recurrent jaundice. Metal stents should only be placed if the patient is deemed to be inoperable. The longevity of metal stents is an important consideration because repeated admissions for clearing or replacement of blocked stents can outweigh any advantage gained by avoiding the initial recovery period in hospital that follows a surgical bypass. It is not acceptable simply to stent a patient who might otherwise be suitable for resection without thorough assessment of the case. In general, very elderly or infirm patients and those with advanced carcinoma (metastatic disease) should be managed by non-operative stenting. For younger patients, those with a potentially resectable tumour and those without extensive distal spread or incipient duodenal obstruction, operative bypass is preferable. The ability to perform biliary and gastric bypass by laparoscopic techniques,4 along with increasing expertise with expandable metal stents in the biliary tract and more recently in the duodenum, means that the surgeon has a wider choice of palliative options and patient selection becomes even more important.

Prepare

1. Patients with prolonged obstruction of the extrahepatic biliary tree tolerate major resectional procedures very poorly. The following specific problems should be anticipated and countered:

Coagulopathy. If hypoprothrombinaemia is present, give sufficient parenteral vitamin K to restore the prothrombin time of the blood to normal. Routine preoperative administration of vitamin K is a sensible precaution in any jaundiced patient.

Coagulopathy. If hypoprothrombinaemia is present, give sufficient parenteral vitamin K to restore the prothrombin time of the blood to normal. Routine preoperative administration of vitamin K is a sensible precaution in any jaundiced patient.

Hepatorenal syndrome. Preoperative rehydration is the simplest and most important precaution. In deeply jaundiced patients, renal failure may be precipitated by intra-operative hypotension, and this should be avoided as far as possible. Catheterize the patient after induction of anaesthesia, ensure adequate hydration and administer intravenous mannitol (40 g) to achieve an osmotic diuresis during the operation.

Hepatorenal syndrome. Preoperative rehydration is the simplest and most important precaution. In deeply jaundiced patients, renal failure may be precipitated by intra-operative hypotension, and this should be avoided as far as possible. Catheterize the patient after induction of anaesthesia, ensure adequate hydration and administer intravenous mannitol (40 g) to achieve an osmotic diuresis during the operation.

Sepsis. Though infected bile is more likely with gallstones than a malignant stricture, ‘invasive’ cholangiography or operation may provoke infection in any obstructed biliary tree. Both procedures should, therefore, be covered by prophylactic antibiotics.

Sepsis. Though infected bile is more likely with gallstones than a malignant stricture, ‘invasive’ cholangiography or operation may provoke infection in any obstructed biliary tree. Both procedures should, therefore, be covered by prophylactic antibiotics.

Malnutrition. Decreased hepatic synthesis of albumin inevitably follows obstructive jaundice and may not improve until the obstruction has been relieved. Consider parenteral nutrition postoperatively if convalescence is prolonged.

Malnutrition. Decreased hepatic synthesis of albumin inevitably follows obstructive jaundice and may not improve until the obstruction has been relieved. Consider parenteral nutrition postoperatively if convalescence is prolonged.

Wound failure. The healing of wounds is impaired in jaundiced patients. Take particular care with abdominal closure.

Wound failure. The healing of wounds is impaired in jaundiced patients. Take particular care with abdominal closure.

2. Preoperative decompression of the obstructed biliary tree is controversial. External transhepatic drainage may improve general health at the risk of various complications (e.g. infection, bile leakage, electrolyte loss). In general, preoperative biliary stents should be reserved for patients with deep and prolonged jaundice or those with complications such as renal insufficiency and cholangitis. Internal decompression by transhepatic or endoscopic retrograde intubation of the stricture is safer but requires appropriate expertise.

Assess

1. If the gallbladder is distended and there is diffuse metastatic spread, indicating that the patient is unlikely to live very long, relieve obstructive jaundice by the simple expedient of cholecystojejunostomy (see Chapter 15). If you are in doubt about the patency of the cystic duct, consider obtaining an operative cholecystogram via a Foley catheter inserted into the fundus. If the extent of disease is known preoperatively, patients with carcinomatosis are better served by non-operative stenting, whereas for those with a better prognosis, but irresectable tumours, the common hepatic duct is better for anastomosis since it prevents recurrence of jaundice from encroachment of tumour on the cystic duct.

2. If the tumour is clearly irresectable, but not as advanced, or alternatively, the gallbladder is collapsed or contains calculi, do not use the gallbladder for anastomosis. More lasting biliary diversion is achieved by choledochojejunostomy Roux-en-Y (see Chapter 15), dividing the bile duct above the ‘leading edge’ of tumour to limit upward spread. Cholecystectomy generally facilitates the operation and is certainly advisable if the gallbladder is obstructed.

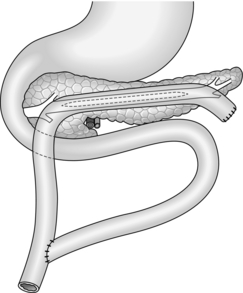

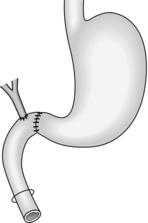

3. If the tumour may be resectable and there are no overt metastases, embark upon a trial dissection. If the superior mesenteric and portal veins can be separated from the neck of pancreas, proceed to pancreatoduodenectomy (see next section).

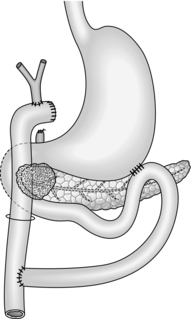

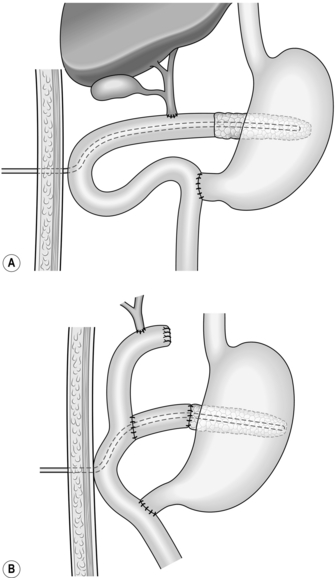

4. You have decided against resection. Be sure that you obtain a positive tissue diagnosis by appropriate biopsy with frozen-section confirmation. Consider palliative procedures to relieve jaundice, vomiting and pain. Carry out biliary diversion as described in paragraphs 1 and 2 above. Unless the prognosis is extremely limited, create an antecolic gastroenterostomy (see Chapter 10) to bypass present or future duodenal obstruction (Fig. 16.7). Alternatively, use the same Roux loop for biliary and gastric bypass (Fig. 16.8).

Fig. 16.8 Single-loop biliary and gastric bypass for an irresectable carcinoma of the head of pancreas. This procedure is an alternative to that shown in Figure 16.7.

5. Options for pain relief include intubated pancreaticogastrostomy, if the pancreatic duct is clearly dilated, or coeliac plexus block; postoperative radiotherapy may also help. An intra-operative nerve block involves injection of 15–20 ml of 50% alcohol on each side at the level of the diaphragmatic crura. Aspirate the syringe each time to ensure that the needle has not entered the aorta or vena cava. Another option is division of the splanchnic nerves within the chest via thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. This minimally invasive procedure has been shown to provide pain relief in some patients with pancreatic cancer, although relief is rarely afforded past 6 months.

6. Palliative resection cannot be justified for adenocarcinomas of the pancreas as positive margins are one of the strongest predictors of poor outcome and survival in this patient group is no better than those undergoing bypass alone.

Aftercare and complications

1. Once the patient recovers from surgery and there is an unequivocal tissue diagnosis, consider the advisability of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy.

2. There is a low risk of leakage from the biliary anastomosis following palliative bypass. Should the leak persist it should be investigated by fistulography and if necessary PTC, with the option for percutaneous stenting of the anastomosis.

3. Occasionally, patients with advanced carcinoma of the pancreas continue to vomit postoperatively despite one or two patent gastric outlets (i.e. pylorus and stoma). A possible mechanism for delayed gastric emptying may be autovagotomy caused by extensive lymph-node spread. Exclude a mechanical obstruction by means of barium meal and/or endoscopy and administer prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide, domperidone and erythromycin.

REFERENCES

1. Hennig R, Tempia-Caliera AA, Hartel M, et al. Staging laparoscopy and its indications in pancreatic cancer patients. Dig Surg 2002;19:484–8.

2. Dickinson KJ, Gomez D, Lowe A, et al. Carcinoma of the body of pancreas in evolution: an aggressive disease affecting younger patients? JOP 2007;8(3):312–9.

3. Kalra MK, Maher MM, Mueller PR, et al. State of the art imaging of pancreatic neoplasms. Br J Radiol 2003;76:857–65.

4. Urbach DR, Swanstrom LL, Hansen PD. The effect of laparoscopy on survival in pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg 2002;137:191–9.

DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY

Appraise

1. Distal pancreatectomy is undertaken for chronic inflammation, trauma or tumour in the body and tail of the gland or as part of a radical gastrectomy for carcinoma of the stomach. In chronic pancreatitis indications include scarring and calcification that are predominantly to the left of the midline, ductal stricture in the neck or body of pancreas and a pseudocyst in the body or tail. Visualization of the surrounding vasculature should be performed preoperatively, using CT or angiography, to look for splenic artery pseudo-aneurysm or splenic vein thrombosis. CT scan, ERCP, MRCP and tests of endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function help in assessing the patient and choosing the best surgical option in chronic pancreatitis.

2. In distal hemipancreatectomy the gland is divided in front of the portal vein, but the resection may be extended to include the neck and part of the head of pancreas. Occasionally performed for diffuse pancreatitis, a subtotal pancreatectomy removes upwards of 80% of the gland. Take care to preserve the bile duct and at least one of the pancreaticoduodenal arteries. Anticipate varying degrees of pancreatic insufficiency such as diabetes and steatorrhoea, depending on the functional status of the residual pancreas. In such extensive disease proximal pancreatoduodenectomy or even total pancreatectomy may be better options (see below).

3. Conventional distal pancreatectomy includes splenectomy. This procedure is indicated for the limited number of ductal carcinomas that are resectable and for most cases of chronic pancreatitis, especially when associated with severe inflammation, pseudocyst and/or splenic vein thrombosis.

4. Conservative distal pancreatectomy involves separating the distal pancreas from the splenic vessels and preserving the spleen. It may be indicated for less severe cases of chronic pancreatitis and for endocrine tumours in the body and tail. It is useful to preserve the immunological function of the spleen and avoid the large dead space that follows splenectomy.

Prepare

1. Distal pancreatectomy can be a difficult and bloody operation. Ensure that cross-matched blood is available.

2. Immunize the patient with the polyvalent anti-pneumococcal vaccine Pneumovax, since these organisms are the most common cause of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection. Current guidelines also include immunization with meningococcal and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines.1 Try to give the vaccines 2–4 weeks before operation for maximum effect.

Assess

1. In operations for chronic pancreatitis the likelihood and extent of resection are indicated by preoperative investigations including endoscopic pancreatography, MRCP, CT and pancreatic function tests. At laparotomy, however, examine the entire gland. Perform operative pancreatography if there is any chance of a dilated ductal system not identified on preoperative imaging, since drainage might be more appropriate than resection in such a case.

2. When operating for upper abdominal trauma, first inspect the liver, spleen and mesentery and deal with any site of bleeding. Pancreatic or duodenal injury should be suspected if there is a retroperitoneal haematoma. Mobilize the duodenum and inspect both surfaces. Enter the lesser sac and examine the pancreas thoroughly. Major contusion or fracture of the pancreatic neck should be treated by distal pancreatectomy.

3. Resection of carcinoma of the body of pancreas is nearly always precluded by direct involvement of the superior mesenteric vessels and/or metastatic spread. Follow the middle colic vein back to find the superior mesenteric vein and establish the relation of this vessel to the tumour. If the main vessels are uninvolved, distal pancreatectomy may be appropriate.

4. Many surgeons remove the left pancreas in a prograde fashion, starting with the tail and proceeding towards the midline; this technique is described below. Increasingly, the authors carry out much of the dissection in a retrograde fashion, mobilizing and dividing the neck of the pancreas at an early stage and, if possible, securing the splenic vessels before elevating the pancreatic tail and body. The prograde technique is especially useful in chronic pancreatitis, in which extensive retropancreatic fibrosis has obscured the anatomical landmarks of the superior mesenteric and portal veins.

Action

Conventional distal pancreatectomy (Fig. 16.9)

1. Start by freeing the neck of pancreas from the underlying portal vein. Trace the middle colic vein downwards to the root of the transverse mesocolon. To display its junction with the superior mesenteric vein it is necessary to incise the peritoneum along the inferior border of the neck and proximal body of pancreas. In chronic pancreatitis this can be a slow and difficult dissection, and a number of small vessels on the pancreas need to be secured. Once the superior mesenteric vein has been exposed, gently develop the plane between the vein and the pancreas. Pass a finger upwards through this tunnel and expose the tip of your finger by dividing the peritoneum along the superior border of the neck of pancreas. Now that the superior mesenteric and portal veins have been freed, it is safe to proceed to mobilize the tail and body of pancreas towards the midline. Alternatively, continue the dissection to the left to identify, ligate and divide the splenic artery and vein before mobilizing the tail of pancreas (see ‘assess’ section, paragraph 4). Ligating the splenic artery prior to the vein reduces bleeding and venous congestion within the spleen.

2. In chronic pancreatitis, especially if there is a pseudocyst, the posterior surface of the stomach and the transverse mesocolon and splenic flexure can become adherent to the distal pancreas and need to be dissected free.

3. Mobilize the spleen upwards by dividing its posterior peritoneal attachment, the posterior layer of the lienorenal ligament. The greater omentum will have been partly divided already in entering the lesser sac; now complete the division. Ligate and divide the short gastric vessels. If the spleen is torn during the dissection, ligate its vascular pedicle and complete the splenectomy at this stage.

4. The pancreatic tail lies at the splenic hilum and has already been partly mobilized. Divide the peritoneum along the upper and lower borders of the distal pancreas. Several small vessels need to be ligated or coagulated by diathermy. Continue the dissection towards the midline, lifting the body and tail of pancreas forwards and to the right. Severe chronic inflammation binds the pancreas firmly to its bed, and sharp dissection is needed to free it posteriorly.

5. As the prograde pancreatic dissection approaches the midline, identify the splenic artery as it reaches the posterior surface of the gland near its upper border. Encircle the vessel with a right-angled Lahey forceps and tie it with stout ligatures (2/0 polyglactin 910), doubly ligating on the proximal side. Ideally, the artery should be tied before the vein to prevent congestion of the spleen, but sometimes it is necessary to ligate and divide the splenic vein first if the artery is encased and inaccessible.

6. The splenic vein can be seen running along the posterior surface of the body of pancreas. As it approaches its right-angled junction with the superior mesenteric vein, it is usually joined by the inferior mesenteric vein. Carefully insert a pair of Lahey forceps between the pancreas and the splenic vein. Ligate and divide the splenic vein, if possible preserving the entry of the inferior mesenteric vein. The pancreas can now be lifted gently off the portal vein. Great care must be taken in the presence of chronic inflammation, since it is easy to tear the veins.

7. Decide where to transect the pancreas: division in front of the portal vein is usual in hemipancreatectomy. Insert 2/0 PDS stay sutures at the upper and lower border of the pancreas at this point and place a soft intestinal clamp across the neck. Divide the pancreas to the left of the clamp and stay sutures and remove the specimen. Be careful not to injure the underlying vein during transection of the gland.

8. Remove the clamp and secure haemostasis. Look for the amputated main pancreatic duct, which normally measures 2–3 mm in diameter at this point. Consider operative pancreatography, and a drainage procedure, if the duct is dilated. Otherwise, under-run the duct with 4/0 PDS and close the pancreatic stump using interrupted 3/0 PDS sutures.

9. Check that the splenic bed and pancreas are dry. Insert one or two tube drains and close the abdomen.

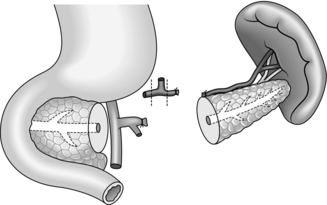

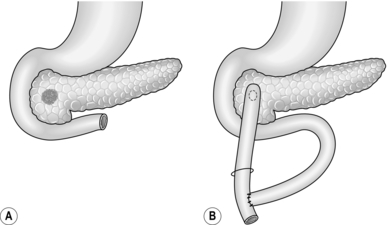

Conservative distal pancreatectomy (Fig. 16.10)

1. The principles of the operation are similar to those for conventional resection, except that an attempt is made to preserve the splenic vessels and spleen. The dissection can be either prograde or retrograde—that is towards, or away from, the midline, or a combination of both. The operation is carried out entirely within the lesser sac without any mobilization of the spleen. This procedure is ideally suited for benign disease and is associated with a significantly lower morbidity rate.2

2. Start by freeing the neck and proximal body of pancreas from the underlying great veins as described above. Select the site of pancreatic transection and insert stay sutures on either side approximately 1 cm apart, one pair on the upper border and one pair on the lower border. Place a Kocher’s director beneath the pancreas to protect the great veins, then incise through the gland with a scalpel on to the director.

3. Secure haemostasis from each cut surface of the pancreas. Identify the proximal pancreatic duct and under-run it with a 4/0 PDS suture. Oversew the pancreatic stump at this point with interrupted 3/0 PDS sutures.

4. Gently elevate the distal pancreas from the underlying splenic vein. Identify the splenic artery as it passes from the coeliac axis to reach the pancreas to the left of the midline. Proceed slowly to free the pancreas from the splenic vessels, ligating and dividing the several arterial and venous branches that connect them.

5. If the pancreas is very adherent to the splenic vessels, it may help to elevate the tail of the gland and dissect progradely towards the site of adherence, thereby approaching it from both sides. It is not uncommon to pull a small branch off the splenic artery or vein and then encounter bleeding. Using a sucker to maintain access, close the defect(s) in the vessel with fine sutures (e.g. 4/0 or 5/0 polypropylene). Sometimes the parent vessel has been sufficiently exposed for a soft vascular clamp to be used for temporary control.

6. Complete the dissection, remove the specimen, check for haemostasis and close the abdomen, leaving a tube drain to the pancreatic bed.

Other techniques

1. If there is concern about the extent of distal resection and the potential for endocrine or exocrine failure, then a middle segment pancreatectomy may be performed.3 Transect the pancreas to the right of the portal vein as described and then, once the gland is mobilized off the splenic vessels, transect it again. Close the proximal stump as for a distal pancreatectomy and anastomose a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum to the tail (see below).

Aftercare

1. Leave the drain(s) for a minimum of 5 days, especially after splenectomy, then shorten and remove them over a period of 2–3 days.

2. If preoperative pancreatic function was normal, a 50–60% distal resection will seldom precipitate serious endocrine or exocrine insufficiency. In a patient with prediabetes or a more extensive pancreatectomy, the blood glucose should be monitored particularly closely and insulin may be required. In any case, repeat exocrine and endocrine function tests before allowing a patient with chronic pancreatitis to return home.

Complications

1. Even with a drain there is a chance of haematoma in the splenic bed and a subsequent left subphrenic abscess. Suspect the diagnosis if the patient develops fever, leucocytosis and a pleural effusion at the left base. Ultrasound or CT scan will confirm the diagnosis and allow percutaneous drainage of the collection.

2. A few patients develop a pancreatic fistula from the cut end of the pancreas, sometimes after percutaneous drainage of a collection. Provided that there is no ductal obstruction in the head of pancreas – and pancreatic ductal imaging with ERCP, MRCP or ductography should have declared this issue – the fistula will close spontaneously, usually within a month of operation. The somatostatin analogue octreotide may possibly hasten closure of a fistula: if it persists, place a pancreatic stent endoscopically or institute nasopancreatic drainage to encourage closure.

REFERENCES

1. Funk EM, Schlimok G, Ehret W, et al. The current status of vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis in splenectomy. I: Adults. Chirurgie 1997;68:586–90.

2. Benoist S, Dugue L, Sauvanet A, et al. Is there a role of preservation of the spleen in distal pancreatectomy? J Am Coll Surg 1999;188:255–60.

3. Warshaw AL, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C, et al. Middle segment pancreatectomy: a novel technique for conserving pancreatic tissue. Arch Surg 1998;133:327–31.

4. Stojadinovic A, Brooks A, Hoos A, et al. An evidence based approach to the surgical management of resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:954–64.

PANCREATICODUDENECTOMY

Appraise

1. Pancreatectomy is undertaken for:

Carcinoma of the head of pancreas

Carcinoma of the head of pancreas

Other less aggressive tumours in this region, loosely called periampullary cancers and including distal cholangiocarcinoma, carcinoma of the ampulla, carcinoma of the duodenum and large neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreatic head

Other less aggressive tumours in this region, loosely called periampullary cancers and including distal cholangiocarcinoma, carcinoma of the ampulla, carcinoma of the duodenum and large neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreatic head

Severe chronic pancreatitis preferentially involving the head of pancreas and sometimes complicated by bile duct stricture or pseudocyst.

Severe chronic pancreatitis preferentially involving the head of pancreas and sometimes complicated by bile duct stricture or pseudocyst.

2. All of these conditions can present with obstructive jaundice, which should be managed as previously described. Particularly in pancreatic cancer, attempt to assess resectability before operation using ultrasound, CT scan and/or angiography to determine the size and extent of the tumour, the presence or absence of lymph node and liver metastases and the all-important relationship of the tumour to major vascular structures, notably the portal vein. Vascular imaging is also useful to show anomalies in arterial supply, notably the right hepatic or common hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery and running up behind the portal vein, which is present in about 25% of patients.

3. Offer pancreaticoduodenectomy for resectable tumours of the pancreatic head, provided that on-table assessment (see below) confirms the absence of distal metastases. There is no absolute upper age limit, but pay particular consideration to patients over the age of 70–75 years because of the extent of the operation required. Palliative procedures for pancreatic cancer have already been described.

4. Neoplastic and inflammatory conditions of the pancreatic head typically present in very different ways. In pancreatic cancer there is a short history of progressive obstructive jaundice with minor or moderate pain, a discrete non-calcified mass on CT scan and an irregular stricture on cholangiography. In chronic pancreatitis there is a long history of abdominal pain associated with weight loss and alcoholism, the jaundice is less severe, remitting or absent and imaging reveals calcification and/or pseudocyst and a smooth tapering stricture in the bile duct. However, the clinical features of the two conditions can overlap sufficiently to be indistinguishable. Resection is the best treatment in either case and obviates the need for biopsy.

5. There is lively debate regarding the best operation for the various conditions described above, but controlled data are scarce. The extent of the operation can be considered under three headings:

The extent of pancreatic resection. For cancer most surgeons perform hemipancreatectomy rather than total pancreatectomy, but for chronic pancreatitis tailor the resection to the distribution of the disease. This question is considered further under ‘Total pancreatectomy’.

The extent of pancreatic resection. For cancer most surgeons perform hemipancreatectomy rather than total pancreatectomy, but for chronic pancreatitis tailor the resection to the distribution of the disease. This question is considered further under ‘Total pancreatectomy’.

The extent of gastroduodenal resection. The occasional benign tumour of the ampulla and small localized ampullary carcinomas in elderly patients may be suitable for a transduodenal ampullectomy, in which the ampulla is circumcised and the terminal portions of bile duct and pancreatic duct are resutured to the duodenal mucosa. The operation of duodenum–preserving resection1 of the head of pancreas has recently been advocated for chronic pancreatitis. The central portion of the head of pancreas is removed, leaving a rim within the duodenal loop, and a Roux loop of jejunum is brought up for anastomosis to the pancreatic duct on either side and sometimes also to the bile duct, if this is strictured or has been entered. With these exceptions, which will not be discussed further because of their limited application, resection of the pancreatic head involves excision of the duodenal loop and terminal bile duct. This pancreatoduodenectomy may be accomplished by conventional or conservative techniques, as described below.

The extent of gastroduodenal resection. The occasional benign tumour of the ampulla and small localized ampullary carcinomas in elderly patients may be suitable for a transduodenal ampullectomy, in which the ampulla is circumcised and the terminal portions of bile duct and pancreatic duct are resutured to the duodenal mucosa. The operation of duodenum–preserving resection1 of the head of pancreas has recently been advocated for chronic pancreatitis. The central portion of the head of pancreas is removed, leaving a rim within the duodenal loop, and a Roux loop of jejunum is brought up for anastomosis to the pancreatic duct on either side and sometimes also to the bile duct, if this is strictured or has been entered. With these exceptions, which will not be discussed further because of their limited application, resection of the pancreatic head involves excision of the duodenal loop and terminal bile duct. This pancreatoduodenectomy may be accomplished by conventional or conservative techniques, as described below.