43

Pain relief in labour

Introduction

Although there is an acceptance, to a degree, that labour is a painful experience, we must guard against the inevitability that labour should be painful. Mothers, especially primigravidae, find it difficult to conceptualize the amount of pain they may experience or their ability to cope with it, until they are in established labour. Mothers may choose to suffer some pain, but the extent to which the mother should experience pain should ideally be agreed, mainly by the mother but in consultation with a midwife and/or obstetrician and/or anaesthetist.

The pain of labour can be severe. It is a complex mix of physiological, psychological and emotional factors and can be difficult to treat. Many different forms of analgesia have been suggested and each has varying efficacies, risk profiles and potential complications.

Pain is unpleasant for the mother, although there is often some amnesia, which can positively influence its perception in retrospect. It is also recognized that the childbirth experience is influenced by maternal expectations and preparation and by the severity of pain in labour.

Factors influencing pain

The severity of labour pain can vary, depending on obstetric, psychological and emotional factors.

Pain scores have been shown to be higher in primigravid women than in multiparous women, especially if they have not had any antenatal preparation. Reports have also shown that primigravid women generally experience more sensory pain during early labour compared with multiparous women, who experience more intense pain much later in labour, as a result of rapid descent of the fetus.

Long labours are perceived as being more painful. Labour is also reported to be more painful with fetal malposition and, in particular, a woman whose baby is occipitoposterior may experience continuous backache and a prolonged labour.

Physiology of labour pain

There are two components to the pain of labour: visceral (relating to an organ, i.e. the uterus) and somatic (relating to other tissues).

Visceral labour pain occurs during the first stage of childbirth and is due to progressive mechanical dilatation of the cervix, distension of the lower uterine segment and contraction of the uterine muscles. Labour pain may also be as result of the myometrial and cervical ischaemia that occurs during contractions. Severity of this pain mirrors the duration and intensity of contractions. Visceral pain is transmitted by small unmyelinated ‘C’ fibres, which travel with sympathetic fibres and pass through the uterine, cervical and hypogastric nerve plexuses into the main sympathetic chain. The pain fibres from the sympathetic chain then enter the white rami communicantes associated with the T10 to L1 spinal nerves and pass via their posterior nerve roots to synapse in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Chemical mediators involved in this pain transmission include bradykinin, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, serotonin, substance P and lactic acid. This pain is dull in character and is sensitive to opioid drugs.

Somatic labour pain occurs during the late first stage and the second stage of labour and is due to stretching and distension of the pelvic floor, perineum and vagina. It occurs as a result of descent of the fetus, and during this stage of labour, the uterus contracts more intensely in a rhythmic and regular manner. Somatic pain is transmitted by fine, myelinated, rapidly transmitting ‘A delta’ fibres. Transmission occurs via the pudendal nerves and perineal branches of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh to S2 to S4 nerve roots. Somatic fibres from the cutaneous branches of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves also carry afferent fibres to L1 and, to some degree, L2.

All resulting nerve impulses (visceral and somatic) pass to dorsal horn cells and finally to the brain via the spinothalamic tract. Direct pressure of the fetus on the lumbosacral plexus also results in neuropathic pain during labour.

Psychology of labour pain

Maternal control makes labour a more positive experience. Attitudes to pain and pain relief in labour depend on personal aspirations, expectations, cultural factors, learned behaviours, peer group influences, desirability of the pregnancy, previous experiences of pain, pre-existing anxiety or depression, and preparation, education and communication.

Methods of pain relief

Non-pharmacological methods

Maternal support

Psychological support is extremely valuable and allows pharmacological intervention to be minimized. With continuous 1:1 support in labour mothers need less analgesia, are more likely to have a vaginal delivery, and are more satisfied with their labour. The supporting person does not need to be the mother’s partner or a midwife, and indeed it may be more useful if they are not part of the mother’s social network at all.

Environment

It is recommended that music of the mother’s choice be played in labour, that light diet be offered, as long as the labour is uncomplicated, and that the mother is encouraged to be mobile, to walk and to try to achieve comfortable positions; it is recognized that pain is increased by being flat on the back. Positions such as squatting, all fours, or a birthing chair or birthing ball may reduce the need for pharmacological pain relief.

Birthing pools

The use of warm baths and birthing pools (Fig. 43.1) has been shown to reduce pain and the need for regional analgesia. These should not be used within 2 h of the administration of opioids or if the mother is drowsy.

Fig. 43.1A birthing pool. (With permission.)

The environment for labour and delivery is important in reducing the need for pharmacological intervention.

Education

Maternal education has some effect in engendering calm and making expectations realistic; this thereby improves control and reduces pain and distress in labour.

Breathing and relaxation techniques, massage, acupuncture, acupressure and hypnosis are used by many women, but have limited evidence to support their effectiveness. There is no evidence that transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS) has any benefit.

Pharmacological methods

Inhaled analgesics

Entonox (a 50:50 mixture of oxygen and nitrous oxide) is commonly used by labouring mothers. Despite its widespread use, studies have shown that it is not a potent analgesic in labour; reassuringly, however, there is moderate evidence for its safety. Any pain relief it offers is limited, and it can lead to nausea, vomiting, drowsiness and light-headedness.

The anaesthetic gases isoflurane, desflurane and sevoflurane can be used safely at sub-anaesthetic concentrations with or without nitrous oxide to improve analgesic efficacy during labour. Although studies have shown that sevoflurane is superior to Entonox in providing pain relief, these gases are not widely available for use in the labour setting.

Systemic opioid analgesia

Systemic opioids have limited effect, irrespective of the drug, the route or the method of administration. There is some limited evidence that intramuscular diamorphine gives more effective analgesia than other opioids, and it may have fewer side-effects. There is the potential for maternal nausea, vomiting and drowsiness, and short-term respiratory depression and drowsiness in the neonate. Opiates should be avoided if delivery is thought to be likely to occur within 4 h of administration. Antiemetics should be administered when parenteral opioids are used.

Pudendal analgesia

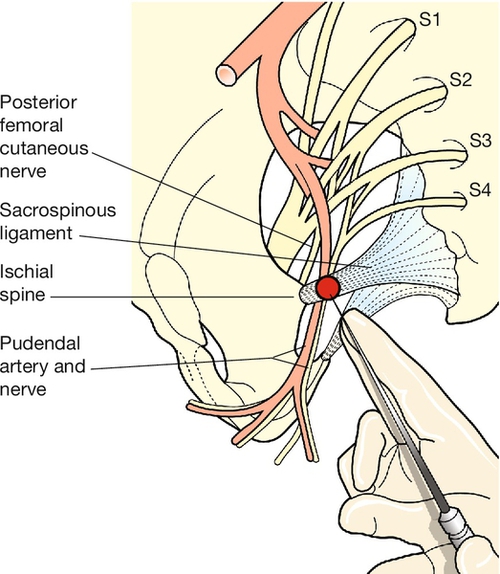

The pudendal nerve, derived from the second, third and fourth sacral nerve roots, supplies the vulva and perineum. It crosses the sacrospinous ligament behind the ischial spine along with the pudendal artery (Fig. 43.2), and local infiltration at this point may provide useful perineal analgesia for a low-outlet forceps or ventouse delivery. A pudendal needle is inserted through the sacrospinous ligament and, after aspirating to ensure that the injection is not intravascular, a local anaesthetic is injected behind the ligament on that side. The injection is repeated on the other side and it is usual to infiltrate the perineum directly at the same time.

Regional analgesia

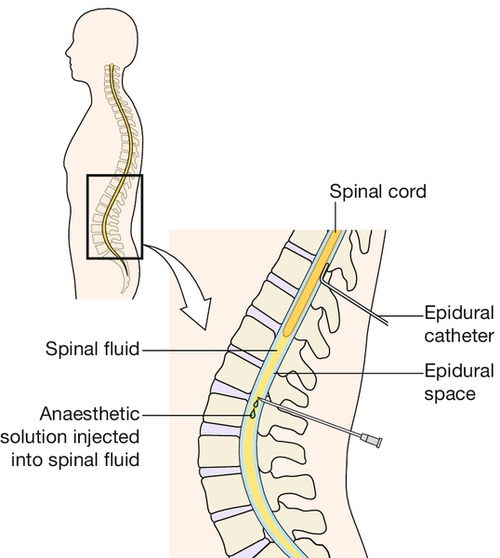

This refers to the delivery of analgesic drugs into the intrathecal (subarachnoid) space (cerebrospinal fluid) or into the epidural space (Fig. 43.3). In obstetric anaesthesia, the introduction of drug to the intrathecal space tends to be known as ‘a spinal’ and the introduction of drug to the epidural space, as ‘an epidural’.

In general, epidurals are used for analgesia in labour, and spinals as a form of anaesthesia for caesarean section and other operative procedures (Table 43.1). The use of regional techniques for anaesthesia has resulted in a reduction in the use of general anaesthesia for caesarean section and other operative procedures. This in turn has had an impact on maternal morbidity and mortality from anaesthetic causes.

Table 43.1

Differences between epidural and spinal analgesia

| Epidural | Spinal |

| Extradural catheter placement | Subarachnoid injection |

| Cannula allows top-up for prolonged use | One-off injection lasting 2–4 h |

| Analgesic effect may be patchy | Dense and relatively reliable anaesthetic blockade |

Epidural analgesia for labour

There is good evidence that epidurals provide more effective pain relief than parenteral opioids. The main indication for epidural analgesia is maternal request, but there may be obstetric indications, e.g. in twin delivery to allow manipulation of the second twin if necessary. Continuous electronic fetal monitoring is recommended. Epidurals do not cause a prolonged first stage, do not lead to an increased rate of caesarean section and are not associated with long-term backache. They have, however, been associated with a prolonged second stage and a higher rate of instrumental delivery, but this may be less of an issue with some lower-dose regimens. The addition of opioid to the epidural solution allows less local anaesthetic use and therefore greater mobility. Epidural analgesia should be continued until after the third stage and for perineal repair if necessary.

Where labour proceeds to a trial of assisted delivery or caesarean section, or complications requiring operative intervention are encountered, the epidural can be topped up or a spinal can be used instead.

Side-effects of epidurals can arise from the mechanical nature of the technique or from the drugs themselves. Neurological complications from mechanical insertion are rare, but inadvertent dural puncture may occur and ongoing CSF leakage following this can lead to a ‘spinal headache’. This leakage can be sealed using a technique known as a ‘blood patch’. Side-effects from the local anaesthetic and opioid are hypotension, urinary retention, pyrexia, pruritus, maternal respiratory depression and neonatal respiratory depression. The hypotension results from sympathetic blockade and peripheral vasodilation, and should be managed by lying the patient in the left lateral position, giving oxygen and treating with either intravenous fluids or vasopressors.

Spinal anaesthesia

Spinals can be used primarily for analgesia, but are more commonly used for anaesthesia before caesarean section, instrumental delivery or the surgical management of postpartum complications, such as a retained placenta or the repair of third- and fourth-degree tears (Fig. 43.4). In obstetric anaesthesia, spinals are invariably carried out as a single shot, which provides a dense block for 2–4 h. As with epidurals, the addition of an opioid allows some sparing of the local anaesthetic volume (and therefore dose), which in turn allows some sparing of the side-effects of sympathetic block.

Complications of spinal anaesthesia can again be considered as related to the procedure and related to the drugs. The mechanical complications are similar to those of the epidural. Hypotension also often occurs, and is managed as above. A high block (which blocks fibres above T4), however, can lead to bradycardia, which in turn compounds any hypotension. A total spinal is a rare complication in which local anaesthetic affects the brain directly and leads to unconsciousness.

Combined spinal–epidural (CSE) is a technique whereby the epidural space is accessed using an epidural needle and then a spinal needle is passed down the epidural needle and advanced to the intrathecal space. ‘Spinal doses’ of drugs are then given down the spinal needle and this needle is removed and an epidural catheter introduced down the epidural needle to the epidural space. The epidural catheter can then be ‘topped up’ as necessary. CSE is used when rapid-onset analgesia is needed but the procedure may be prolonged, such that epidural top-ups may be needed too, or when the patient’s condition cannot risk the potential sympathetic block, which might occur with a full spinal (cardiac disease) or a high motor block (respiratory disease); a smaller-dose spinal can then be used, with the facility to top this up epidurally.

General anaesthesia

General anaesthesia in pregnancy carries more risk than in the non-pregnant patient. As there is reduced gastro-oesophageal tone, increased intra-abdominal mass and reduced gastric emptying, regurgitation of gastric contents and aspiration of these to the lungs is more likely. In addition, as the gastric contents are more acidic in pregnancy, any aspiration is more likely to lead to pneumonitis. Difficult and failed intubation is more likely than in non-pregnant patients because of pregnancy-related obesity. Regional anaesthesia is therefore to be preferred if possible.