Chapter 72 Pain Management in The Intensive Care Unit

3 How can pain be assessed in critically ill patients?

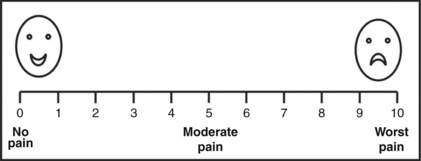

Pain should be assessed and documented at regular intervals. Pain is a subjective experience and is most reliably measured by using a subjective scale such as the numeric rating scale (Fig. 72-1), which can be employed in patients as young as 5 years. Younger patients’ pain is assessed by using the faces scale (Fig. 72-1), which is a modified visual analog scale. In patients unable to communicate, reliance on objective measures (physiologic or behavioral) becomes necessary. Whereas use of physiologic measures (blood pressure, heart rate, tearing, diaphoresis, mydriasis) can cause underreporting and overreporting of pain, use of behavioral measures such as observation of facial expression has been demonstrated to correlate with subjective reporting.

5 What are the treatment options for a critically ill patient in pain?

Nonpharmacologic treatment of pain includes proper positioning of patients, stabilization of fractures, elimination of irritating physical stimulation, and environmental modification to promote comfort. Because sleep deprivation as well as anxiety and delirium may diminish the pain threshold, it is important to minimize stimuli that can disturb the normal diurnal sleep pattern (noise, artificial light) and treat anxiety and delirium promptly.

Nonpharmacologic treatment of pain includes proper positioning of patients, stabilization of fractures, elimination of irritating physical stimulation, and environmental modification to promote comfort. Because sleep deprivation as well as anxiety and delirium may diminish the pain threshold, it is important to minimize stimuli that can disturb the normal diurnal sleep pattern (noise, artificial light) and treat anxiety and delirium promptly.

Pharmacologic treatment of pain works by inhibition of the release of local mediators in damaged tissue (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDS], acetaminophen), blocking nerve conduction (regional anesthesia), or altering pain neurotransmission in the central nervous system (opioids, acetaminophen, ketamine, dexmedetomidine).

Pharmacologic treatment of pain works by inhibition of the release of local mediators in damaged tissue (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDS], acetaminophen), blocking nerve conduction (regional anesthesia), or altering pain neurotransmission in the central nervous system (opioids, acetaminophen, ketamine, dexmedetomidine).

7 Which opioids are recommended for routine administration in ICU patients?

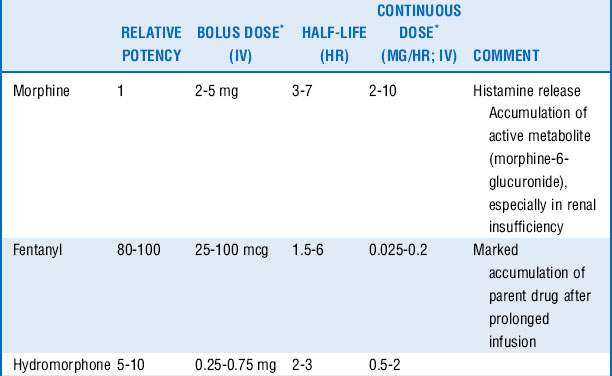

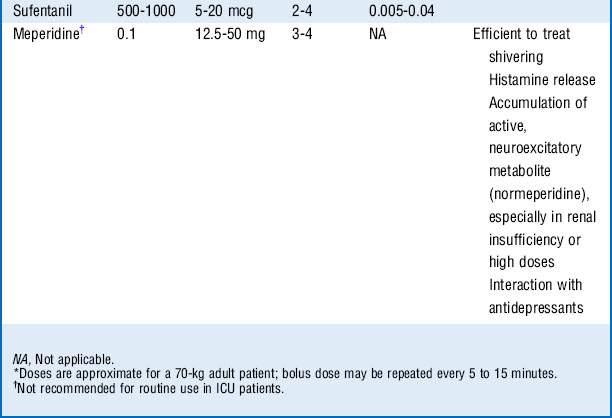

Morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, and sufentanil are the analgesic agents most commonly used and recommended in the ICU (Table 72-1).

8 How do you decide which opioid to use?

Morphine is a naturally occurring, relatively hydrophilic opioid with a long clinical history and therefore familiarity with its use. The onset of action is slow (effect site equilibration time 15-30 minutes), and duration of action is 2 to 4 hours. However, it has relatively rapid hepatic clearance and tends not to accumulate because of its water solubility, which limits the volume of distribution, although glucuronide metabolites with sedative-analgesic properties may accumulate in the setting of renal insufficiency.

Morphine is a naturally occurring, relatively hydrophilic opioid with a long clinical history and therefore familiarity with its use. The onset of action is slow (effect site equilibration time 15-30 minutes), and duration of action is 2 to 4 hours. However, it has relatively rapid hepatic clearance and tends not to accumulate because of its water solubility, which limits the volume of distribution, although glucuronide metabolites with sedative-analgesic properties may accumulate in the setting of renal insufficiency.

Fentanyl is a synthetic, potent, and highly lipid-soluble opioid. The lipid solubility is responsible for the rapid onset of action (effect site equilibration time 1-3 minutes). This makes it a preferable analgesic in the acutely distressed patient. Fentanyl has a short duration of action (30-45 minutes after one bolus); however, repeated dosing may cause accumulation and prolonged action (long context-sensitive half-life). Cardiovascular side effects are minimal.

Fentanyl is a synthetic, potent, and highly lipid-soluble opioid. The lipid solubility is responsible for the rapid onset of action (effect site equilibration time 1-3 minutes). This makes it a preferable analgesic in the acutely distressed patient. Fentanyl has a short duration of action (30-45 minutes after one bolus); however, repeated dosing may cause accumulation and prolonged action (long context-sensitive half-life). Cardiovascular side effects are minimal.

Hydromorphone is a semisynthetic opioid that is approximately 10 times more potent than morphine and has lipid solubility between those of morphine and fentanyl. Compared with morphine, its onset and duration of action are slightly shorter (effect site equilibration time 10-20 minutes, duration of action 1-3 hours). There is less histamine release and greater hemodynamic stability, and there is no clinically significant active metabolite.

Hydromorphone is a semisynthetic opioid that is approximately 10 times more potent than morphine and has lipid solubility between those of morphine and fentanyl. Compared with morphine, its onset and duration of action are slightly shorter (effect site equilibration time 10-20 minutes, duration of action 1-3 hours). There is less histamine release and greater hemodynamic stability, and there is no clinically significant active metabolite.

Sufentanil is a synthetic, highly lipid-soluble opioid with high selectivity for the μ-receptor. It has been shown to cause less respiratory depression compared with other opioids; thus it may be preferred in patients with spontaneous ventilation. Sufentanil accumulates less compared with fentanyl (shorter context-sensitive half-life).

Sufentanil is a synthetic, highly lipid-soluble opioid with high selectivity for the μ-receptor. It has been shown to cause less respiratory depression compared with other opioids; thus it may be preferred in patients with spontaneous ventilation. Sufentanil accumulates less compared with fentanyl (shorter context-sensitive half-life).

10 Which other opioids should be avoided in the ICU for routine analgesia?

Mixed agonist-antagonists (e.g., nalbuphine) may reverse other opioids and may precipitate a withdrawal syndrome in patients in whom tolerance or dependence has developed.

Mixed agonist-antagonists (e.g., nalbuphine) may reverse other opioids and may precipitate a withdrawal syndrome in patients in whom tolerance or dependence has developed.

Methadone prolongs the QT interval and can induce torsades de pointes ventricular arrhythmia. It is metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P-450 system, and a risk exists for drug interactions and accumulation after repeated dosing.

Methadone prolongs the QT interval and can induce torsades de pointes ventricular arrhythmia. It is metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P-450 system, and a risk exists for drug interactions and accumulation after repeated dosing.

Codeine is not useful for most patients because it lacks analgesic efficacy.

Codeine is not useful for most patients because it lacks analgesic efficacy.

11 How should opioids be administered for acute pain management in the ICU?

IV bolus injections are often used for moderate pain. The doses are titrated to analgesic requirements avoiding respiratory depression and hemodynamic instability.

IV bolus injections are often used for moderate pain. The doses are titrated to analgesic requirements avoiding respiratory depression and hemodynamic instability.

In clinical situations with moderate to severe pain, which is only poorly controlled with repeated boluses, a continuous IV infusion may be considered.

In clinical situations with moderate to severe pain, which is only poorly controlled with repeated boluses, a continuous IV infusion may be considered.

Alternatively, a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) regimen may be preferable in conscious patients.

Alternatively, a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) regimen may be preferable in conscious patients.

14 What are the side effects of opioids? (See Table 72-2.)

| Central nervous system | Miosis Euphoria, dysphoria, sedation Addiction |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary | Respiratory depression Muscle rigidity (especially highly lipid-soluble opioids) |

| Cardiovascular | Bradycardia, hypotension |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea, emesis Constipation, ileus |

| Urogenital | Urinary retention Antidiuretic hormone release (water retention) |

| Other | Histamine release: flushing, tachycardia, hypotension, bronchospasm Pruritus |

15 What is the role of nonopioid analgesics in the ICU, and what are their characteristics?

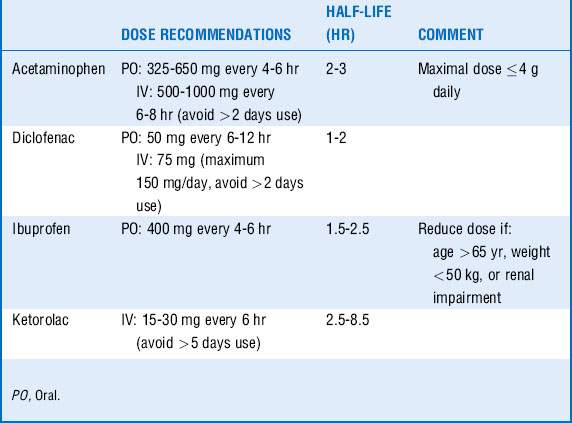

Acetaminophen and NSAIDs have been shown to decrease the need for opioids and are particularly effective in reducing muscular and skeletal pain. They are often more effective than opioids in reducing pain from pleural or pericardial rubs, a pain that responds poorly to opioids. Basic pharmacology is summarized in Table 72-3.

16 What are the side effects of nonopioid analgesics?

Acetaminophen may be potentially hepatotoxic, especially in patients with depleted glutathione stores. Therefore acetaminophen should be avoided in acute liver failure, and the drug should be maintained at less than 2 g/day in patients with a significant history of alcohol intake or poor nutritional status.

Acetaminophen may be potentially hepatotoxic, especially in patients with depleted glutathione stores. Therefore acetaminophen should be avoided in acute liver failure, and the drug should be maintained at less than 2 g/day in patients with a significant history of alcohol intake or poor nutritional status.

NSAIDs may cause bleeding as a result of platelet function inhibition, gastrointestinal side effects such as ulcers and bleeding, and the development of acute renal failure. Risk factors for the development of acute renal failure are patient age, preexisting renal impairment, hypovolemia, and shock. The prolonged use of NSAIDs should be avoided. For example, it has been shown that ketorolac applied for ≥ 5 days has been associated with a twofold increased risk of acute renal failure. Furthermore, NSAIDs should be avoided in patients with asthma and aspirin allergy. The role of the newer NSAIDs in the ICU, the selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, remains unknown. Although initially believed to offer protection from the renal and gastrointestinal side effects of traditional nonselective NSAIDs, this does not appear to be the case as both the gut and kidney depend on constitutive activity of the COX-2 enzyme to regulate organ perfusion.

NSAIDs may cause bleeding as a result of platelet function inhibition, gastrointestinal side effects such as ulcers and bleeding, and the development of acute renal failure. Risk factors for the development of acute renal failure are patient age, preexisting renal impairment, hypovolemia, and shock. The prolonged use of NSAIDs should be avoided. For example, it has been shown that ketorolac applied for ≥ 5 days has been associated with a twofold increased risk of acute renal failure. Furthermore, NSAIDs should be avoided in patients with asthma and aspirin allergy. The role of the newer NSAIDs in the ICU, the selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, remains unknown. Although initially believed to offer protection from the renal and gastrointestinal side effects of traditional nonselective NSAIDs, this does not appear to be the case as both the gut and kidney depend on constitutive activity of the COX-2 enzyme to regulate organ perfusion.

20 Is epidural analgesia safe in the setting of deep vein thromboprophylaxis?

Regional anesthesia may be performed in this setting, although practitioners are advised to follow the guidelines of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (www.asra.com) and be vigilant for the development of epidural hematoma. If low-dose unfractionated heparin is being used, needle placement and/or catheter removal should be done ≥ 2 hours after discontinuing heparin, and reheparinization may be started ≥ 1 hour after an uncomplicated epidural insertion. If fractionated low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is being used in prophylactic doses, a waiting period of ≥ 12 hours for any neuraxial technique should be applied after the last dose of LMWH, and the next LMWH dose should be given ≥ 2 hours after an uncomplicated procedure.

1 Bonnet F., Marret E. Influence of anaesthetic and analgesic techniques on outcome after surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:52–58.

2 Domino E. Taming the ketamine tiger. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:678–684.

3 Jacobi J., Fraser G.L., Coursin D.B., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:119–141.

4 Mehta S., McCullagh I., Burry L. Current sedation practices: lessons learned from international surveys. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:471–488.

5 Riker R.R., Shehabi Y., Bokesch P.M., et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for sedation of critically ill patients: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:489–499.