Chapter 31 Pain Management for the Postoperative Cardiac Patient

Adequate postoperative analgesia prevents unnecessary patient discomfort, may decrease morbidity, may decrease postoperative hospital length of stay, and thus may decrease cost. Because postoperative pain management has been deemed important, the American Society of Anesthesiologists has published practice guidelines regarding this topic.1 Furthermore, in recognition of the need for improved pain management, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has developed new standards for the assessment and management of pain in accredited hospitals and other health care settings.2 Patient satisfaction (no doubt linked to adequacy of postoperative analgesia) has become an essential element that influences clinical activity of not only anesthesiologists but also all health care professionals.

Achieving optimal pain relief after cardiac surgery is often difficult. Pain may be associated with many interventions, including sternotomy, thoracotomy, leg vein harvesting, pericardiotomy, and/or chest tube insertion, among others. Inadequate analgesia and/or an uninhibited stress response during the postoperative period may increase morbidity by causing adverse hemodynamic, metabolic, immunologic, and hemostatic alterations. Aggressive control of postoperative pain, associated with an attenuated stress response, may decrease morbidity and mortality in high-risk patients after noncardiac surgery and may also decrease morbidity and mortality in patients after cardiac surgery. Adequate postoperative analgesia may be attained via a wide variety of techniques (Table 31-1). Traditionally, analgesia after cardiac surgery has been obtained with intravenous opioids (specifically morphine). However, intravenous opioid use is associated with definite detrimental side effects (nausea/vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, respiratory depression), and longer-acting opioids such as morphine may delay tracheal extubation during the immediate postoperative period via excessive sedation and/or respiratory depression. Thus, in the current era of early extubation (“fast-tracking”), cardiac anesthesiologists are exploring unique options other than traditional intravenous opioids for control of postoperative pain in patients after cardiac surgery.3 No single technique is clearly superior; each possesses distinct advantages and disadvantages. It is becoming increasingly clear that a multimodal approach/combined analgesic regimen (utilizing a variety of techniques) is likely the best way to approach postoperative pain (in all patients after surgery) to maximize analgesia and minimize side effects. When addressing postoperative analgesia in cardiac surgical patients, choice of technique (or techniques) is made only after a thorough analysis of the risk/benefit ratio of each technique in the specific patient in whom analgesia is desired.

| Local anesthetic infiltration |

| Nerve blocks |

| Opioids |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents |

| α-Adrenergic agents |

| Intrathecal techniques |

| Epidural techniques |

| Multimodal analgesia |

PAIN AND CARDIAC SURGERY

Surgical or traumatic injury initiates changes in the peripheral and central nervous systems that must be addressed therapeutically to promote postoperative analgesia and, it is hoped, positively influence clinical outcome (Boxes 31-1 and 31-2). The physical processes of incision, traction, and cutting of tissues stimulate free nerve endings and a wide variety of specific nociceptors. Receptor activation and activity are further modified by the local release of chemical mediators of inflammation and sympathetic amines released via the perioperative surgical stress response. The perioperative surgical stress response peaks during the immediate postoperative period and exerts major effects on many physiologic processes. The potential clinical benefits of attenuating the perioperative surgical stress response (above and beyond simply attaining adequate clinical analgesia) have received much attention during the past decade and remain fairly controversial. However, it is clear that inadequate postoperative analgesia and/or an uninhibited perioperative surgical stress response has the potential to initiate pathophysiologic changes in all major organ systems, including the cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, renal, endocrine, immunologic, and/or central nervous systems, all of which may lead to substantial postoperative morbidity.

Persistent pain after cardiac surgery, although rare, can be problematic.4 The cause of persistent pain after sternotomy is multifactorial, yet tissue destruction, intercostal nerve trauma, scar formation, rib fractures, sternal infection, stainless-steel wire sutures, and/or costochondral separation may all play roles. Such chronic pain is often localized to the arms, shoulders, or legs. Postoperative brachial plexus neuropathies may also occur and have been attributed to rib fracture fragments, internal mammary artery dissection, suboptimal positioning of patients during surgery, and/or central venous catheter placement. Postoperative neuralgia of the saphenous nerve has also been reported after harvesting of saphenous veins for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Younger patients appear to be at higher risk for developing chronic, long-lasting pain. The correlation of severity of acute postoperative pain and development of chronic pain syndromes has been suggested (patients requiring more postoperative analgesics may be more likely to develop chronic pain), yet the causative relationship is still vague.

POTENTIAL CLINICAL BENEFITS OF ADEQUATE POSTOPERATIVE ANALGESIA

Inadequate analgesia (coupled with an uninhibited stress response) during the postoperative period may lead to many adverse hemodynamic (tachycardia, hypertension, vasoconstriction), metabolic (increased catabolism), immunologic (impaired immune response), and hemostatic (platelet activation) alterations. In patients undergoing cardiac surgery, perioperative myocardial ischemia (diagnosed by electrocardiography and/or transesophageal echocardiography) is most commonly observed during the immediate postoperative period and appears to be related to outcome. Intraoperatively, initiation of CPB causes substantial increases in stress response hormones (e.g., norepinephrine, epinephrine) that persist into the immediate postoperative period and may contribute to myocardial ischemia observed during this time. Furthermore, postoperative myocardial ischemia may be aggravated by cardiac sympathetic nerve activation, which disrupts the balance between coronary blood flow and myocardial oxygen demand. Thus, during the pivotal immediate postoperative period after cardiac surgery, adequate analgesia (coupled with stress-response attenuation) may potentially decrease morbidity and enhance health-related quality of life.5

TECHNIQUES AVAILABLE FOR POSTOPERATIVE ANALGESIA

Local Anesthetic Infiltration

Pain after cardiac surgery is often related to median sternotomy (peaking during the first 2 postoperative days). One method that may hold promise is continuous infusion of local anesthetic (Box 31-3). In a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial, White and associates6 studied 36 patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Intraoperative management was standardized. All patients had two indwelling infusion catheters placed at the median sternotomy incision site at the end of surgery (one in the subfascial plane above the sternum, one above the fascia in the subcutaneous tissue). Patients received 0.25% bupivacaine (n = 12), 0.5% bupivacaine (n = 12), or normal saline (n = 12) via a constant rate infusion through the catheter (4 mL/hr) for 48 hours after surgery. Average times to tracheal extubation were similar in the three groups (5 to 6 hours). Compared with the control group (normal saline), there was a statistically significant reduction in verbal rating scale pain scores and patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) using intravenous morphine in the 0.5% bupivacaine group. Patient satisfaction with their pain management was also improved in the 0.5% bupivacaine group (vs. control). However, there were no significant differences in PCA morphine use between the 0.25% bupivacaine and control groups. Although tracheal extubation time and the duration of the intensive care unit (ICU) stay (30 hours vs. 34 hours, respectively) were not significantly altered, time to ambulation (1 day vs. 2 days, respectively) and duration of hospital stay (4.2 days vs. 5.7 days, respectively) were lower in the 0.5% bupivacaine group than in the control group.

Nerve Blocks

With the increasing popularity of minimally invasive cardiac surgery, which utilizes nonsternotomy incisions (minithoracotomy), the use of nerve blocks for the management of postoperative pain has increased as well (Box 31-4).7 Thoracotomy incisions (transverse anterolateral minithoracotomy, vertical anterolateral minithoracotomy), owing to costal cartilage trauma tissue damage to ribs, muscles, or peripheral nerves, may induce more intense postoperative pain than that resulting from median sternotomy. Adequate analgesia after thoracotomy is important because pain is a key component in alteration of lung function after thoracic surgery. Uncontrolled pain causes a reduction in respiratory mechanics, reduced mobility, and increases in hormonal and metabolic activity. Perioperative deterioration in respiratory mechanics may lead to pulmonary complications and hypoxemia, which may in turn lead to myocardial ischemia/infarction, cerebrovascular accidents, thromboembolism, and delayed wound healing, leading to increased morbidity and prolonged hospital stay. Various analgesic techniques have been developed to treat postoperative thoracotomy pain. The most commonly used techniques include intercostal nerve blocks, intrapleural administration of local anesthetics, and thoracic paravertebral blocks. Intrathecal techniques and epidural techniques are also very effective in controlling post-thoracotomy pain.

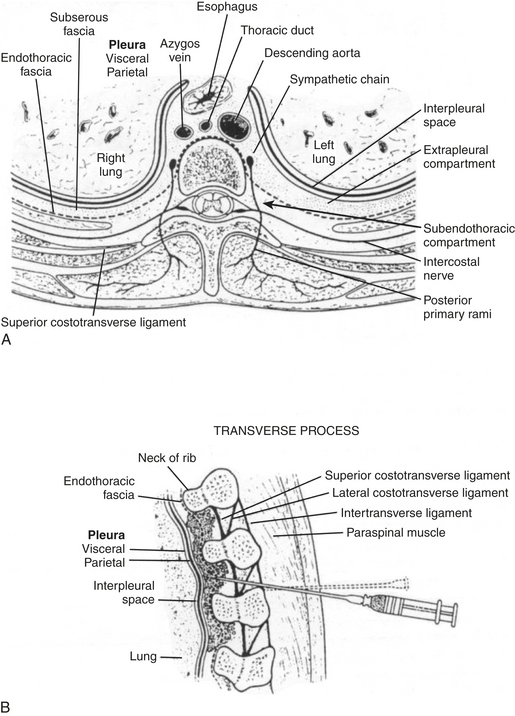

Thoracic paravertebral block involves injection of local anesthetic adjacent to the thoracic vertebrae close to where the spinal nerves emerge from the intervertebral foramina (Fig. 31-1). Thoracic paravertebral block, compared with thoracic epidural analgesic techniques, appears to provide equivalent analgesia, is technically easier, and may harbor less risk. Several different techniques exist for successful thoracic paravertebral block and have been extensively reviewed.8 The classic technique, most commonly used, involves eliciting loss of resistance. Injection of local anesthetic results in ipsilateral somatic and sympathetic nerve blockade in multiple contiguous thoracic dermatomes above and below the site of injection (along with possible suppression of the neuroendocrine stress response to surgery). These blocks may be effective in alleviating acute and chronic pain of unilateral origin from the chest and/or abdomen. Bilateral use of thoracic paravertebral block has also been described. Continuous thoracic paravertebral infusion of local anesthetic via a catheter placed under direct vision at thoracotomy is also a safe, simple, and effective method of providing analgesia after thoracotomy. It is usually used in conjunction with adjunct intravenous medications (opioid or other analgesics) to provide optimum relief after thoracotomy.

Opioids

Beginning in the 1960s, large doses of intravenous opioids have been administered to patients undergoing cardiac surgery (Box 31-5). Because even very large amounts of intravenous opioids do not initiate “complete anesthesia” (unconsciousness, muscle relaxation, suppression of reflex responses to noxious surgical stimuli), other intravenous/inhalation agents must be administered during the intraoperative period. Analgesia is the best known and most extensively investigated opioid effect, yet opioids are also involved in a diverse array of other physiologic functions, including control of pituitary and adrenal medulla hormone release and activity, control of cardiovascular and gastrointestinal function, and the regulation of respiration, mood, appetite, thirst, cell growth, and the immune system. A number of well-known and potential side effects of opioids (nausea and vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, respiratory depression) may limit postoperative recovery when opioids are used for postoperative analgesia.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents

The NSAIDs, in contrast to the opioids’ central nervous system mechanism of action, mainly exert their analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory effects peripherally by interfering with prostaglandin synthesis after tissue injury (Box 31-6).9 NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin. Combining NSAIDs with traditional intravenous opioids may allow a patient to achieve an adequate level of analgesia with fewer side effects than if a similar level of analgesia was obtained with intravenous opioids alone. Numerous clinical investigations reveal the potential value (opioid-sparing effects) of NSAIDs when combined with traditional intravenous opioids during the postoperative period after noncardiac surgery. In fact, the administration of NSAIDs is one of the most common nonopioid analgesic techniques currently used for postoperative pain management. The efficacy of NSAIDs for postoperative pain has been repeatedly demonstrated in many analgesic clinical trials. Unlike opioids, which preferentially reduce spontaneous postoperative pain, NSAIDs have comparable efficacy for both spontaneous and movement-evoked pain, the latter of which may be more important in causing postoperative physiologic impairment. Certainly, NSAIDs reduce postoperative opioid consumption and accelerate postoperative recovery and represent an integral component of balanced postoperative analgesic regimens after noncardiac surgery. However, little is known regarding NSAID use in the management of pain after cardiac surgery. It is likely that concerns regarding NSAID side effects, including alterations in the gastric mucosal barrier, renal tubular function, and inhibition of platelet aggregation, have made clinicians reluctant to use NSAIDs in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Other rare side effects of NSAIDs (from COX inhibition) include hepatocellular injury, asthma exacerbation, anaphylactoid reactions, tinnitus, and urticaria. Despite these fears, a small number of clinical investigations seem to indicate that NSAIDs may provide analgesia in patients after cardiac surgery without untoward effects (e.g., gastrointestinal ulceration, renal dysfunction, excessive bleeding).

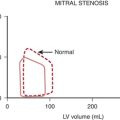

NSAIDs are not a homogeneous group and vary considerably in analgesic efficacy as a result of differences in pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters. NSAIDs are nonspecific inhibitors of COX, which is the rate-limiting enzyme involved in the synthesis of prostaglandins. A major scientific discovery revealed that COX exists in multiple forms. Most important, a constitutive form is present in normal conditions in healthy cells (COX-1) and an inducible form (COX-2) exists that is the major isozyme induced by and associated with inflammation. Simplistically, COX-1 is ubiquitously and constitutively expressed and has a homeostatic role in platelet aggregation, gastrointestinal mucosal integrity, and renal function, whereas COX-2 is inducible and expressed mainly at sites of injury (and kidney and brain) and mediates pain and inflammation. NSAIDs are nonspecific inhibitors of both forms of COX yet vary in their ratio of COX-1 to COX-2 inhibition. Recent molecular studies distinguishing between constitutive COX-1 and inflammation-inducible COX-2 enzymes have led to the exciting hypothesis that the therapeutic and adverse effects of NSAIDs could be uncoupled (Fig. 31-2).10

α2-Adrenergic Agonists

The α2-adrenergic agonists provide analgesia, sedation, and sympatholysis (Box 31-7). The potential perioperative analgesic benefits of α2-agonists, when administered to patients undergoing cardiac surgery, were demonstrated almost 20 years ago. Most of the clinical investigations regarding perioperative use of this class of drugs remain focused on exploiting the sedative effects and beneficial cardiovascular effects (decreasing hypertension and tachycardia) associated with their use. α2-Adrenergic agonists have been used perioperatively in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, yet the focus of such clinical investigations has been on the intraoperative period and the potential for enhanced postoperative hemodynamic stability, potentially leading to reduced postoperative myocardial ischemia (not specifically at enhanced postoperative analgesia).

Intrathecal and Epidural Techniques

It is clear from numerous clinical investigations that intrathecal and/or epidural techniques (using opioids and/or local anesthetics) initiate reliable postoperative analgesia in patients after cardiac surgery (Boxes 31-8 and 31-9). Additional potential advantages of using intrathecal and/or epidural techniques in patients undergoing cardiac surgery include stress-response attenuation and thoracic cardiac sympathectomy.

Intrathecal Techniques

Most clinical investigators have used intrathecal morphine in hopes of providing prolonged postoperative analgesia. Some clinical investigators have used intrathecal fentanyl, sufentanil, and/or local anesthetics for intraoperative anesthesia and analgesia (with stress response attenuation) and/or thoracic cardiac sympathectomy. An anonymous survey of members of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists indicates that almost 8% of practicing anesthesiologists incorporate intrathecal techniques into their anesthetic management of adults undergoing cardiac surgery.11 Of these anesthesiologists, 75% practice in the United States, 72% perform the intrathecal injection before induction of anesthesia, 97% use morphine, 13% use fentanyl, 2% use sufentanil, 10% use lidocaine, and 3% use tetracaine.

The mid 1990s saw the emergence of fast-track cardiac surgery, with the goal being tracheal extubation in the immediate postoperative period. Chaney and associates in 199712 were the first to study the potential clinical benefits of intrathecal morphine when used in patients undergoing cardiac surgery and early tracheal extubation. They prospectively randomized 40 patients to receive either intrathecal morphine (10 μg/kg) or intrathecal placebo before induction of anesthesia for elective CABG. Intraoperative anesthetic management was standardized (intravenous fentanyl, 20 μg/kg, and intravenous midazolam, 10 mg) and postoperatively all patients received intravenous morphine via PCA exclusively. Of the patients who were tracheally extubated during the immediate postoperative period, the mean time from ICU arrival to tracheal extubation was significantly (P = .02) prolonged in patients who received intrathecal morphine (10.9 ± 4.4 hours) compared with placebo controls (7.6 ± 2.5 hours). Three patients who received intrathecal morphine had tracheal extubation substantially delayed (12 to 24 hours) because of prolonged ventilatory depression (likely secondary to intrathecal morphine). Although the mean postoperative intravenous morphine use for 48 hours was less in patients who received intrathecal morphine (42.8 mg) compared with patients who received intrathecal placebo (55.0 mg), the difference between groups was not statistically significant. No clinical differences existed between groups regarding postoperative morbidity, mortality, or duration of postoperative hospital stay (approximately 9 days in each group).

These somewhat discouraging findings (absence of enhanced analgesia, prolongation of tracheal extubation time) stimulated the same group of investigators in 1999 to try again, this time decreasing the amount of intraoperative intravenous fentanyl patients received (hoping to decrease fentanyl’s effect on augmenting postoperative respiratory depression associated with intrathecal morphine).13 Forty patients were prospectively randomized to receive either intrathecal morphine (10 μg/kg) or intrathecal placebo before induction of anesthesia for elective CABG. Intraoperative anesthetic management was standardized (intravenous fentanyl, 10 μg/kg, and intravenous midazolam, 200 μg/kg) and all patients postoperatively received intravenous morphine exclusively via PCA. Of the patients tracheally extubated during the immediate postoperative period, mean time to tracheal extubation was similar in patients who received intrathecal morphine (6.8 ± 2.8 hours) compared with intrathecal placebo patients (6.5 ± 3.2 hours). However, once again, four patients who received intrathecal morphine had tracheal extubation substantially delayed (14, 14, 18, and 19 hours) because of prolonged respiratory depression (likely secondary to intrathecal morphine). The mean postoperative intravenous morphine use during the immediate postoperative period was actually higher in patients receiving intrathecal morphine (49.8 mg) compared with patients receiving intrathecal placebo (36.2 mg), yet the difference between groups was not statistically significant. No clinical differences existed between groups regarding postoperative morbidity, mortality, or duration of postoperative hospital stay (approximately 6 days in each group). Thus, Chaney and associates, from their three prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical investigations in the late 1990s involving 140 healthy adults undergoing elective CABG, concluded that although intrathecal morphine certainly can initiate reliable postoperative analgesia, its use in the setting of fast-track cardiac surgery and early tracheal extubation may be detrimental by potentially delaying tracheal extubation in the immediate postoperative period.

Epidural Techniques

Most clinical investigators have used thoracic epidural local anesthetics in hopes of providing perioperative stress response attenuation and/or perioperative thoracic cardiac sympathectomy. Some clinical investigators have used thoracic epidural opioids to provide intraoperative and/or postoperative analgesia. An anonymous survey of members of the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists indicates that 7% of practicing anesthesiologists incorporate thoracic epidural techniques into their anesthetic management of adults undergoing cardiac surgery.11 Of these anesthesiologists, 58% practice in the United States. Regarding the timing of epidural instrumentation, 40% perform instrumentation before induction of general anesthesia, 12% perform instrumentation after induction of general anesthesia, 33% perform instrumentation at the end of surgery, and 15% perform instrumentation on the first postoperative day.

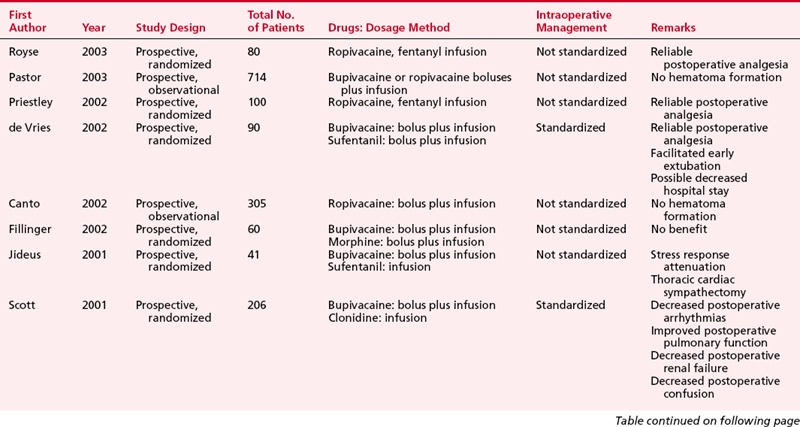

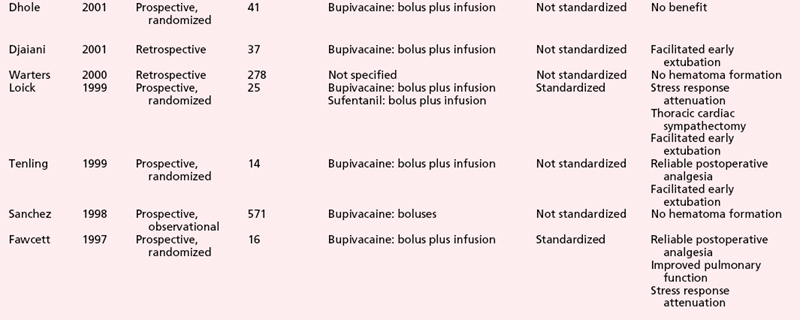

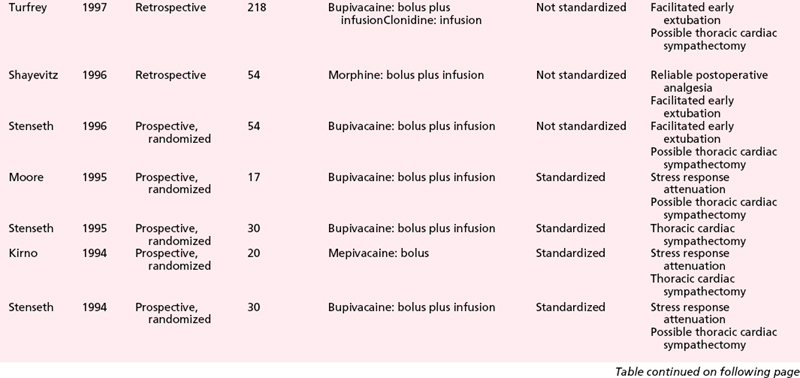

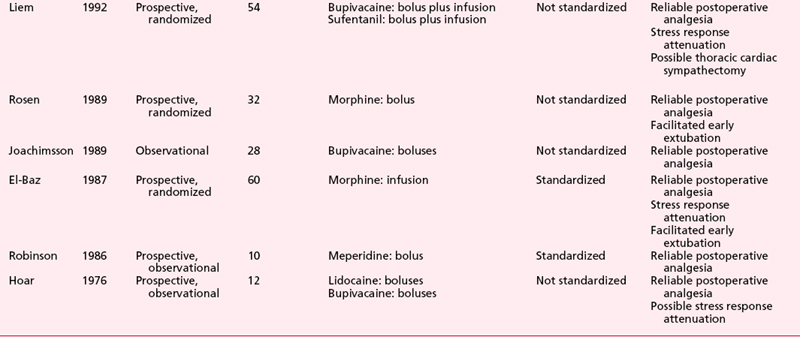

Numerous clinical studies further attest to the ability of thoracic epidural anesthesia and analgesia with local anesthetics and/or opioids to induce substantial postoperative analgesia in patients after cardiac surgery (Table 31-2).

A relatively large clinical investigation highlights the potential clinical benefits of thoracic epidural anesthesia in cardiac surgical patients. Scott and associates14 prospectively randomized (nonblinded) 420 patients undergoing elective CABG to receive either thoracic epidural anesthesia (bupivacaine/clonidine) and general anesthesia or general anesthesia alone (control group). The two groups received similar intraoperative anesthetic techniques. In thoracic epidural anesthesia patients, the thoracic epidural infusion was continued for 96 hours after surgery (titrated according to need). In control patients, target-controlled infusion alfentanil was used for the first 24 postoperative hours, then followed by PCA morphine for the next 48 hours. Postoperatively, striking clinical differences were observed between the two groups. Postoperative incidence of supraventricular arrhythmia, lower respiratory tract infection, renal failure, and acute confusion were all significantly lower in patients receiving thoracic epidural anesthesia compared with control patients.

In contrast to the encouraging findings of the clinical investigation by Scott and associates, other prospective, randomized, nonblinded clinical investigations reveal that using thoracic epidural anesthesia techniques in patients undergoing cardiac surgery may not offer substantial clinical benefits.15 In 2002, Priestley and associates prospectively randomized 100 patients undergoing elective CABG to receive either thoracic epidural anesthesia (ropivacaine/fentanyl) and general anesthesia or general anesthesia alone (control group). The two groups received quite different intraoperative anesthetic techniques. Postoperatively, thoracic epidural anesthesia patients received epidural ropivacaine/fentanyl for 48 hours (supplemental analgesics available if needed), whereas control patients received nurse-administered intravenous morphine, followed by PCA morphine. Patients receiving thoracic epidural anesthesia were extubated sooner than controls (3.2 vs. 6.7 hours, respectively; P < .001), yet this difference may have been secondary to the different amounts of intraoperative intravenous opioid administered to the two groups (intraoperative intravenous anesthetic technique not standardized). Postoperative pain scores at rest were significantly lower in patients receiving thoracic epidural anesthesia only on postoperative days 0 and 1 (equivalent on days 2 and 3). Postoperative pain scores during coughing were significantly lower in patients receiving thoracic epidural anesthesia only on postoperative day 0 (equivalent on days 1, 2, and 3). There were no significant differences between the two groups in postoperative oxygen saturation on room air, chest radiograph changes, or spirometry. Furthermore, no clinical differences were detected between the two groups regarding postoperative mobilization goals, atrial fibrillation, postoperative hospital discharge eligibility, or actual postoperative hospital discharge.

A 2004 meta-analysis by Liu and associates16 assessed effects of perioperative central neuraxial analgesia on outcome after CABG. These authors, via MEDLINE and other databases, searched for randomized controlled trials in patients undergoing CABG with CPB. Fifteen trials enrolling 1178 patients were included for thoracic epidural anesthesia analysis, and 17 trials enrolling 668 patients were included for intrathecal analysis. Thoracic epidural techniques did not affect the incidences of mortality or myocardial infarction yet reduced risk of arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation and tachycardia), reduced risk of pulmonary complications (pneumonia and atelectasis), reduced time to tracheal extubation, and reduced analog pain scores. Intrathecal techniques did not affect incidences of mortality, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, or time to tracheal extubation and only modestly decreased systemic morphine utilization and pain scores (while increasing incidence of pruritus). These authors conclude that central neuraxial analgesia does not affect rates of mortality or myocardial infarction after CABG yet is associated with improvements in faster time to tracheal extubation, decreased pulmonary complications and cardiac arrhythmias, and reduced pain scores. However, the authors also note that the majority of potential clinical benefits offered by central neuraxial analgesia (earlier extubation, decreased arrhythmias, enhanced analgesia) may be reduced and/or eliminated with changing cardiac anesthesia practice using fast-track techniques, use of β-adrenergic blockers or amiodarone, and/or use of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors. These authors also note that the risk of spinal hematoma (addressed later in this chapter) due to central neuraxial analgesia in patients undergoing full anticoagulation for CPB remains uncertain.

RISK OF HEMATOMA FORMATION

Although most investigators agree that risk of hematoma is likely increased when intrathecal or epidural instrumentation is performed in patients before systemic heparinization required for CPB, the absolute degree of increased risk is somewhat controversial; some believe the risk may be as high as 0.35%. An extensive mathematical analysis by Ho and associates17 of the approximately 10,840 intrathecal injections in patients subjected to systemic heparinization required for CPB (without a single episode of hematoma formation) reported in the literature as of the year 2000 estimated that the minimum risk of hematoma formation was 1:220,000 and the maximum risk of hematoma formation was 1:3600 (95% confidence level); however, the maximum risk may be as high as 1:2400 (99% confidence level). Similarly, of the approximately 4583 epidural instrumentations in patients subjected to systemic heparinization required for CPB (without a single episode of hematoma formation) reported in the literature as of the year 2000, the minimum risk of hematoma formation was 1:150,000 and the maximum risk of hematoma formation was 1:1500 (95% confidence level); however, the maximum risk may be as high as 1:1000 (99% confidence level).

Use of regional anesthetic techniques in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, while seemingly increasing in popularity, remains extremely controversial, prompting numerous editorials by recognized experts in the field of cardiac anesthesia.18 One of the main reasons such controversy exists (and likely will continue for some time) is that the numerous clinical investigations regarding this topic are suboptimally designed and use a wide array of disparate techniques, preventing clinically useful conclusions on which all can agree.

CONCLUSIONS

Multiple factors are important during the perioperative period that potentially affect outcome and quality of life after cardiac surgery, including type and quality of surgical intervention, extent of postoperative neurologic dysfunction, myocardial dysfunction, pulmonary dysfunction, renal dysfunction, coagulation abnormalities, quality of postoperative analgesia, and/or extent of systemic inflammatory response, among others19 (Table 31-3). This list of factors is presented in no particular order; obviously, depending on specific clinical situations (e.g., surgical procedure, patient comorbidity), certain factors will be more important than others. It is extremely difficult (if not impossible) to determine exactly how important attaining adequate postoperative analgesia truly is in relation to all of these clinical factors surrounding apatient undergoing cardiac surgery. A clear link between “adequate” or “high-quality”postoperative analgesia and outcome in patients after cardiac surgery has yet to be established.20

| Type and quality of surgical intervention |

| Extent of postoperative neurologic dysfunction |

| Extent of postoperative myocardial dysfunction |

| Extent of postoperative pulmonary dysfunction |

| Extent of postoperative renal dysfunction |

| Extent of postoperative coagulation abnormalities |

| Quality of postoperative analgesia |

| Extent of systemic inflammatory response |

SUMMARY

1. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management: Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1573.

2. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations: Pain assessment and management: An organizational approach. 2000. Available at http://www.jcaho.org.

3. Myles P.S., Daly D.J., Djaiani G., et al. A systematic review of the safety and effectiveness of fast-track cardiac anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:982.

4. Kalso E., Mennander S., Tasmuth T., Nilsson E. Chronic post-sternotomy pain. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2001;45:935.

5. Wu C.L., Naqibuddin M., Rowlingson A.J., et al. The effect of pain on health-related quality of life in the immediate postoperative period. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1078.

6. White P.F., Rawal S., Latham P., et al. Use of a continuous local anesthetic infusion for pain management after median sternotomy. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:918.

7. Riedel B.J. Regional anesthesia for major cardiac and noncardiac surgery: More than just a strategy for effective analgesia? (editorial). J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2001;15:279.

8. Myles P. Underutilization of paravertebral blocks in thoracic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:635.

9. Ralley F.E., Day F.J., Cheng D.C.H. Pro: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be routinely administered for postoperative analgesia after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:731.

10. Kharasch E.D. Perioperative COX-2 inhibitors: Knowledge and challenges [editorial]. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1.

11. Goldstein S., Dean D., Kim S.J., et al. A survey of spinal and epidural techniques in adult cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2001;15:158.

12. Chaney M.A., Furry P.A., Fluder E.M., Slogoff S. Intrathecal morphine for coronary artery bypass grafting and early extubation. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:241.

13. Chaney M.A., Nikolov M.P., Blakeman B.P., Bakhos M. Intrathecal morphine for coronary artery bypass graft procedure and early extubation revisited. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13:574.

14. Scott N.B., Turfrey D.J., Ray D.A.A., et al. A prospective randomized study of the potential benefits of thoracic epidural anesthesia and analgesia in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:528.

15. Priestley M.C., Cope L., Halliwell R., et al. Thoracic epidural anesthesia for cardiac surgery: The effects on tracheal intubation time and length of hospital stay. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:275.

16. Liu S.S., Block B.M., Wu C.L. Effects of perioperative central neuraxial analgesia on outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery: A meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:153.

17. Ho A.M.H., Chung D.C., Joynt G.M. Neuraxial blockade and hematoma in cardiac surgery: Estimating the risk of a rare adverse event that has not (yet) occurred. Chest. 2000;117:551.

18. Gravlee G.P. Epidural analgesia and coronary artery bypass grafting: The controversy continues [editorial]. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:151.

19. Myles P.S., Hunt J.O., Fletcher H., et al. Relation between quality of recovery in hospital and quality of life at 3 months after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:862.

20. Wu C.L., Raja S.N. Optimizing postoperative analgesia: The use of global outcome measures [editorial]. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:533.