Objectives

• Explain the physiology of pain.

• Discuss how to perform a pain assessment in the critically ill patient.

• Identify patient and health care professional barriers to a pain assessment.

• Describe the pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions for pain management.

• Describe nursing interventions that are essential in the treatment of acute pain.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Despite national and international efforts, guidelines, standards of practice, position statements, and many important discoveries in the field of pain management in the past three decades, pain remains a major stressor for patients in critical care settings.1 Because many sources of pain are present in critical care settings, such as acute illness, surgery, trauma, invasive equipment, and nursing and medical interventions,2,3 it is not surprising that more than 50% of critically ill patients experience moderate to severe pain.4–6 In a large, international study involving 5957 critically ill adults, the Thunder Project II sponsored by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), turning, drain removal, wound care, and endotracheal suctioning were described as painful procedures of moderate to severe intensity.5 Despite these findings, pain remains undertreated in most critically ill patients.4,6–9 In the Thunder Project II, less than 20% of critically ill adults received opiates before and during painful procedures.9 Poor treatment of acute pain may lead to the development of serious complications10,11 and chronic pain syndromes,12,13 which may seriously impact the patient’s functioning, quality of life, and well-being.

Importance of Pain Assessment

To detect pain, it must be adequately assessed. Because pain is recognized as a subjective experience,14 the patient’s self-report is the most valid measure for pain. Unfortunately in critical care, many factors alter verbal communication with patients: the administration of sedative agents, mechanical ventilation, and the patient’s change in level of consciousness.2,3,15 Nevertheless, except for being unable to speak, many mechanically ventilated patients can communicate that they are in pain by using head nodding, grimacing, hand motions, or by seeking attention with other movements.4,16

Pain scales have been used with postoperative mechanically ventilated patients who were asked to point on the pain intensity scale to communicate their pain.5,17,18 However, in a study of mechanically ventilated adults with various diagnoses (trauma, surgical, or medical), only one third of mechanically ventilated patients were able to use a pain intensity scale.19 With a greater degree of critical illness, providing a pain intensity self-report becomes more difficult because it requires concentration and energy. When the patient is unable to express himself or herself in any way, observable, clustered behavioral and physiological indicators become unique indices for pain assessment and are part of clinical guidelines and recommendations developed in North America.20–23 Many health care agencies have increased their vigilance regarding patients’ pain and its management, including designating pain assessment as the fifth vital sign, as stated by the American Pain Society.

Definition and Description of Pain

Pain is described as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.14 This definition emphasizes its subjective and multidimensional nature. Its subjective characteristic implies that pain is whatever the person experiencing it says it is and that pain exists whenever he or she says it does.24 This definition implies that the patient is able to self-report. In the critical care context, many patients are unable to self-report.25

Infants represent a unique group of vulnerable patients who cannot self-report their pain and therefore communicate by behaviors. Clinicians must be attuned to infant’s behaviors for pain-related clinical assessment.25 This same principle applies to any nonverbal population, for whom behavioral alterations caused by pain are valuable forms of self-report and should be considered as alternative measures of pain.25 Based on this idea, pain assessment must be designed to conform to the patient’s communication capabilities, and this is consistent with the fact that pain is multidimensional.

Components of Pain

The experience of pain includes sensory, affective, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological components:26,27

Types of Pain

Pain can be acute or chronic, with different sensations related to the origin of the pain.

Acute Pain

Acute pain has a short duration, represents tissue damage from an identifiable cause, and corresponds to the healing process (30 days). Undertreated prolonged acute pain can become chronic pain.12,13

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain persists for longer than 3 to 6 months after the healing process from the original injury.28,29 It develops when the healing process is incomplete or with permanent damage to the nervous system. It has also been associated with a prolonged stress response.27 Acute and chronic types of pain can have a nociceptive or neuropathic origin.30

Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain refers to the nociception mechanism, and can be somatic or visceral. Somatic pain involves superficial tissues, including skin, muscles, joints, and bones; the location is well defined; and it may be described as tender, burning, shooting or throbbing. Visceral pain involves organs including the heart, stomach, and liver; location is diffuse, and it is usually described as aching or cramping.

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic or deafferentation pain is described as an abnormal sensory process caused by changes in the excitability of nerve cells.31 These changes are associated with the acute inflammatory process or with nerve damage that can be caused by surgery or an illness process.32–34 The origin of the pain may be peripheral or central.

Pain in Critical Care

Pain in the critical care setting is a subjective and multidimensional experience. Its components are sensory, affective, cognitive, behavioral, and physiological. Pain experienced by critical care patients is mostly acute with multiple origins. An understanding of pain physiology provides the foundation for assessment and treatment.

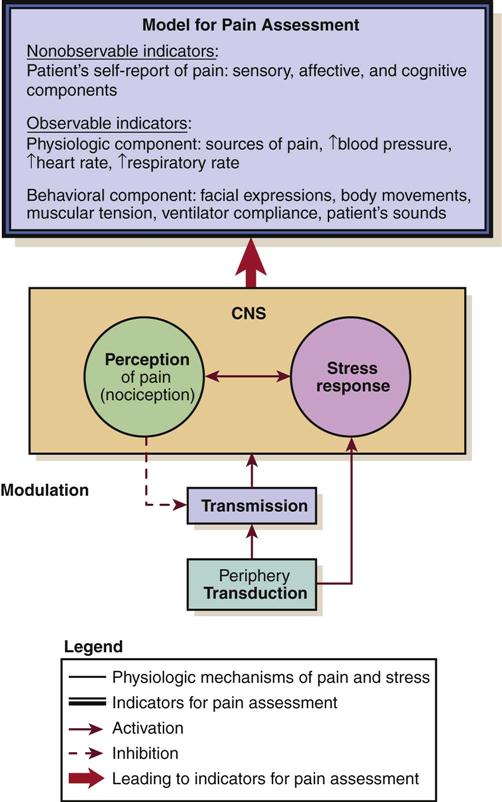

Physiology of Pain

Nociception

Nociception represents the neural and brain activity that is necessary, but not sufficient, for pain. Pain is the conscious experience that emerges from nociception, especially from brain activity.35 Four processes are involved in nociception:30

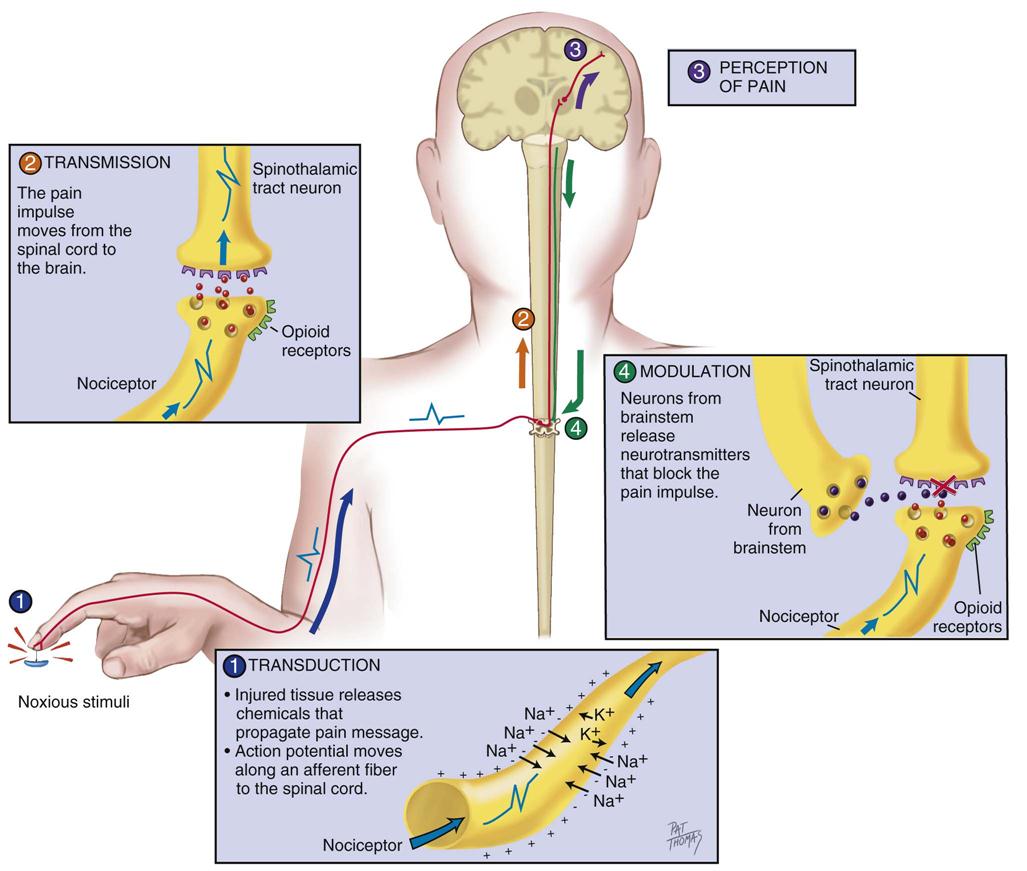

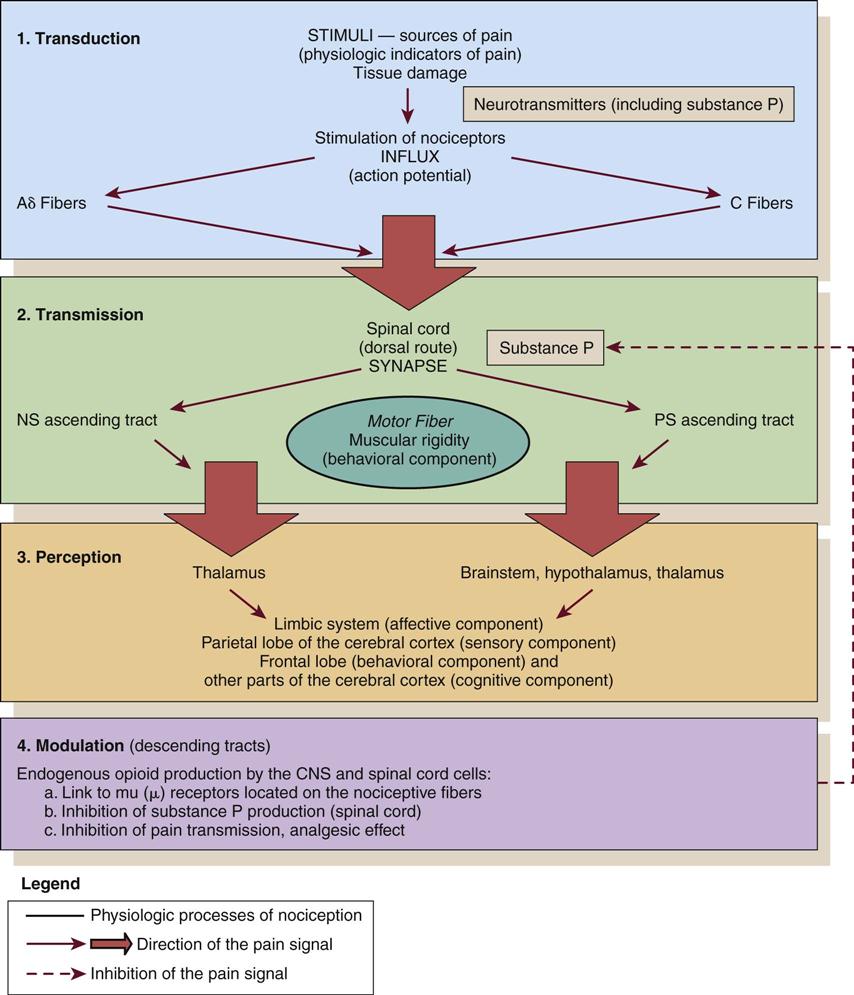

These four processes are shown in Figure 8-1 and Figure 8-2, which integrates pain assessment with nociception.

CNS, central nervous system; NS, neospinothalamic pathway; PS, paleospinothalamic pathway. (Copyright Céline Gélinas, School of Nursing, McGill University, Canada.)

Transduction

Transduction refers to mechanical (e.g., surgical incision), thermal (e.g., burn), or chemical (e.g., toxic substance) stimuli that damage tissues. These stimuli activate the liberation of chemical substances, such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, glutamate, and substance P, which stimulate peripheral nociceptive receptors and initiate nociceptive transmission.

Transmission

As a result of transduction, an action potential is produced and transmitted by nociceptive nerve fibers in the spinal cord that reach higher centers of the brain. This is called transmission, and it represents the second process of nociception. The principal nociceptive fibers are the Aδ and C fibers. These fibers synapse with two spinothalamic pathways: neospinothalamic (NS) and paleospinothalamic (PS) pathways. Generally, the Aδ fibers transmit the pain sensation to the brain within the NS pathway, and the C fibers use the PS pathway.36

Through synapsing of nociceptive fibers with motor fibers in the spinal cord, muscle rigidity can appear because of a reflex activity.10 Muscle rigidity can be a behavioral indicator associated with pain. It can contribute to immobility and decrease diaphragmatic excursion. This can lead to hypoventilation and hypoxemia. Hypoxemia can be detected by a pulse oximeter (SpO2) and by oxygen arterial pressure (PaO2) monitoring. A ventilated patient’s interaction with the machine (e.g., activation of alarms, fighting the ventilator) also may indicate the presence of pain.37

Perception

The pain message is transmitted via the spinothalamic pathways to centers in the brain where pain is initially perceived. Pain sensation transmitted by the NS pathway reaches the thalamus, and the pain sensation transmitted by the PS pathway reaches brainstem, hypothalamus, and thalamus.36 Projections to the limbic system and the frontal cortex allow expression of the affective component of pain.38–40 Projections to the sensory cortex located in the parietal lobe allow the patient to describe the sensory characteristics of his or her pain, such as location, intensity, and quality.38–42 The cognitive component of pain involves many parts of the cerebral cortex and is complex. These three components (affective, sensory, and cognitive) represent the subjective interpretation of pain. Parallel to this subjective process, certain facial expressions and body movements are behavioral indicators of pain occurring as a result of pain fiber projections to the motor cortex in the frontal lobe.

Modulation

Modulation is the liberation of endogenous opioids, such as β-endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins, by the CNS. Through the descending pathways endogenous opioids inhibit the transmission of pain sensation in the spinal cord and produce analgesia. These substances link to mu (µ) receptors located on nociceptive fibers, inhibiting the liberation of substance P and blocking the transmission of the pain sensation.

Pain Assessment

Pain assessment is a vital part of nursing care. It is a prerequisite for adequate pain control and relief. Pain is a subjective, multidimensional concept that requires complex assessment. Pain assessment has two major components: nonobservable/subjective and observable/objective.

Pain Assessment: The Subjective Component

Pain is an entirely subjective experience.14,47–49 The subjective component of pain assessment refers to the patient’s self-report of pain. Because it is the most valid measure, the patient’s self-report must be obtained whenever possible.21 A simple yes or no (presence versus absence of pain) is considered a valid self-report. Mechanical ventilation should not be a barrier to document patients’ self-reports of pain. Many mechanically ventilated patients can communicate that they have pain or can use pain scales by pointing to numbers or symbols on the scale.4,5,17–19 Before concluding that a patient is unable to self-report, three attempts to ask the patient about pain are recommended.3 Sufficient time should be allowed for the patient to respond with each attempt.

If sedation and cognition levels allow the patient to give more information about pain, a multidimensional assessment can be documented. Multidimensional pain assessment tools, including the sensorial, emotional, and cognitive components, are available (e.g., Brief Pain Inventory,50 Initial Pain Assessment Tool,30 Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire51). Because of the administration of sedative and analgesic agents in mechanically ventilated patients, the tool must be short enough to be completed. For instance, the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire takes 2 to 3 minutes to complete and has been used to assess mechanically ventilated patients who were in stable condition.5,17,18

The patient’s self-report of pain can also be obtained by questioning the patient using the mnemonic PQRSTU:52

• P: provocative and palliative or aggravating factors

• R: region or location, radiation

P: Provocative and Palliative or Aggravating Factors

The P investigates what provokes or causes the pain, and the moderating factors that reduce pain or discomfort.

Q: Quality

The Q in the mnemonic refers to the pain sensation that the patient is experiencing. For instance, the patient may describe the pain as dull, aching, sharp, burning, or stabbing. This information provides the nurse with data regarding the type of pain the patient is experiencing (i.e., somatic or visceral). The differentiation between types of pain may contribute to the determination of cause and management. A patient who has had open-heart surgery may complain of chest pain that is shooting or burning.4 This information can lead the nurse to investigate for cutaneous or bone injuries as a result of a sternotomy. Another patient may describe a sharp thoracic pain that may lead the nurse to consider visceral pain as a result of pulmonary embolism. A verbal description of pain is important because it provides a baseline account, allowing the critical care nurse to monitor changes in the type of pain, which may indicate a change in the underlying pathology.

R: Region or Location, Radiation

R usually is easy for the patient to identify, although visceral pain is more difficult for the patient to localize.30 If the patient has difficulty naming the location or is mechanically ventilated, ask that the patient to point to the location on himself or herself or on a simple anatomic drawing.53

S: Severity and Other Symptoms

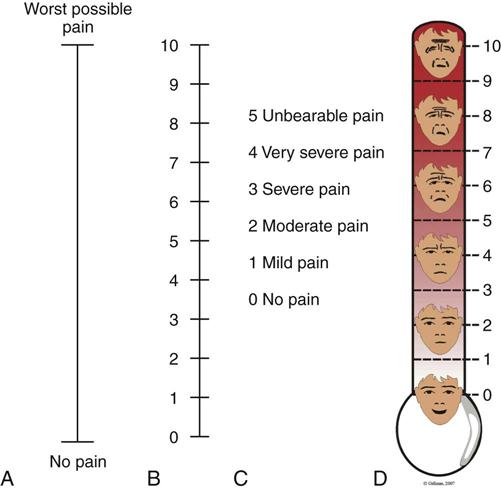

S denotes pain severity or intensity. Many visual analog scales are available, as are the descriptive and numeric pain rating scales used in critical care (Figure 8-3). Numeric and descriptive pain rating scales have been used to assess pain in mechanically ventilated patients.5,19,46 The Faces Pain Rating Scale was identified as the easiest pain intensity scale by adults in acute and critical care settings.54,55 To have a faces scale more specific to adults, Gélinas56 developed and validated the Faces Pain Thermometer (FPT) for critically ill patients.

A, Visual analog scale (VAS). B, Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). C, Descriptive Rating Scale (DRS). D, Faces Pain Thermometer. (Copyright Céline Gélinas, School of Nursing, McGill University, Canada.)

Asking the patient to grade the pain on a scale of 0 to 10 is a consistent method and aids the nurse in objectifying the subjective nature of the patient’s pain.

The S in the mnemonic also refers to other symptoms accompanying the pain experience, such as shortness of breath, nausea, and fatigue. Anxiety and fear are common emotions associated with pain.

T: Timing

The T refers to documenting the onset, duration, and frequency of pain. This information can help determine whether the pain is acute or chronic. Duration of pain can indicate the severity of the problem.

U: Understanding

The U in the mnemonic is the patient’s perception of the problem or cognitive experience of pain.

Nurses should start by asking, “Do you have pain?” The use of a simple yes or no question allows the patient to answer verbally or indicate a response by a nod of the head or other signs.3 Pain intensity and location also are necessary for the initial assessment of pain.53

Pain Assessment: The Observable or Objective Component

When the patient’s self-report is impossible to obtain, nurses can rely on observation of behavioral and physiological indicators that are strongly recommended for pain management in nonverbal patients.20–22 Pain-related behaviors have received attention in critical care and were also studied in the AACN Thunder Project II.57 Patients who experienced pain during nociceptive procedures were three to ten times more likely to have increased behavioral responses such as facial expressions, body movement responses, and verbal responses than patients without pain. Similar observations were found in a study of 257 mechanically ventilated adults in critical care. Patients who experienced pain during turning showed more intense facial expressions (e.g., grimacing), muscle rigidity, and ventilator dyssynchrony compared with patients without pain.58

Behavioral indicators are strongly recommended for pain assessment in nonverbal patients,21,25 and several tools have been developed and tested in critically ill adults: Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS),43–45 Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT),59 Post Anesthesia Care Unit Behavioral Pain Rating Scale (PACU-BPRS),60 Pain Behavioral Assessment Tool (PBAT),57 and Pain Assessment and Intervention Notation (PAIN) algorithm.46 The BPS and the CPOT are supported by experts as appropriate for use with uncommunicative critically ill adults61,62 and by the clinical practice recommendations of a task force of the American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN).21 The implementation of pain assessment tools is essential so that health care teams can establish a common language of communication. This facilitates inter-professional collaboration and benefits patients.

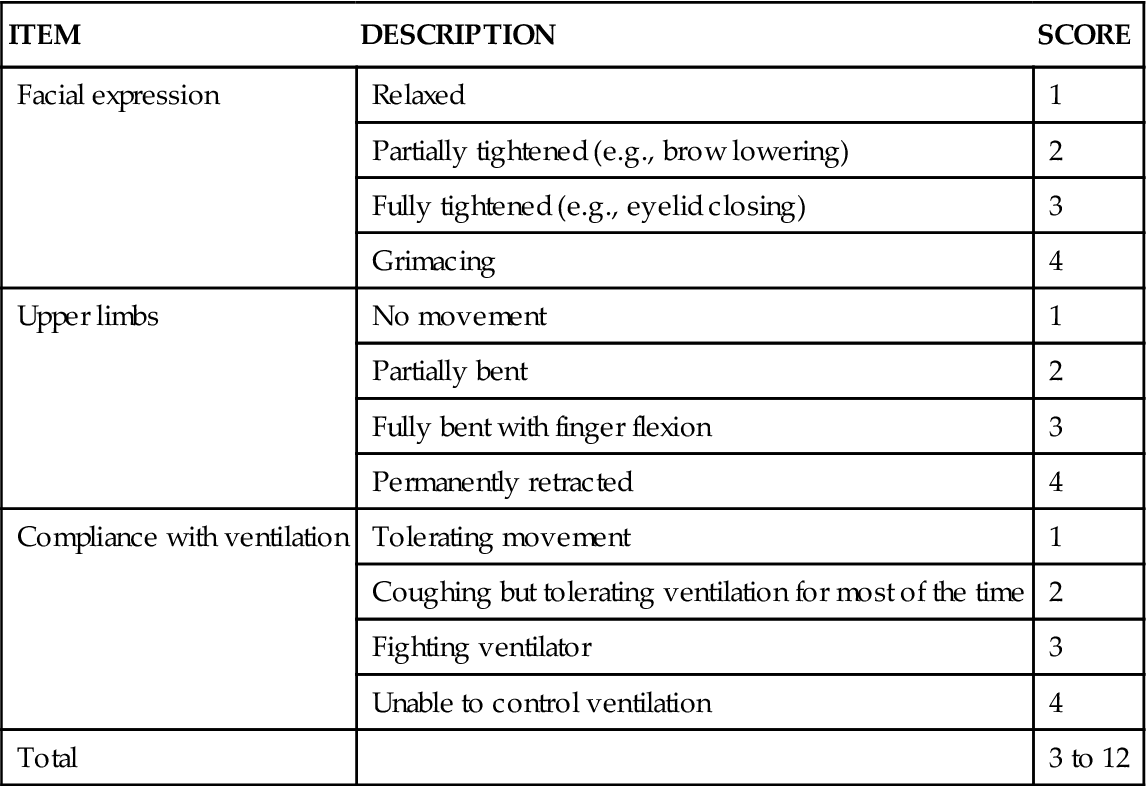

Behavioral Pain Scale

The BPS shown in Table 8-1 was mainly tested in mechanically ventilated, unconscious patients.43,45,63,64 Its validity was supported with significantly higher BPS scores during nociceptive procedures (e.g., turning, endotracheal suctioning) compared with rest or nonnociceptive procedures (e.g., central venous catheter dressing change, compression stocking applications, eye care). Most clinicians were satisfied with its ease of use, but some expressed concerns about its relative complexity.45 For instance, scores of 3 and 4 for compliance with the ventilator may be ambiguous, and movements with upper limbs may be confused with muscle tension.61

TABLE 8-1

| ITEM | DESCRIPTION | SCORE |

| Facial expression | Relaxed | 1 |

| Partially tightened (e.g., brow lowering) | 2 | |

| Fully tightened (e.g., eyelid closing) | 3 | |

| Grimacing | 4 | |

| Upper limbs | No movement | 1 |

| Partially bent | 2 | |

| Fully bent with finger flexion | 3 | |

| Permanently retracted | 4 | |

| Compliance with ventilation | Tolerating movement | 1 |

| Coughing but tolerating ventilation for most of the time | 2 | |

| Fighting ventilator | 3 | |

| Unable to control ventilation | 4 | |

| Total | 3 to 12 |

From Payen JF, et al: Assessing pain in the critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale, Crit Care Med 29(12):2258, 2001.

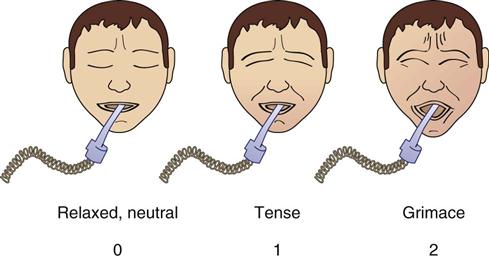

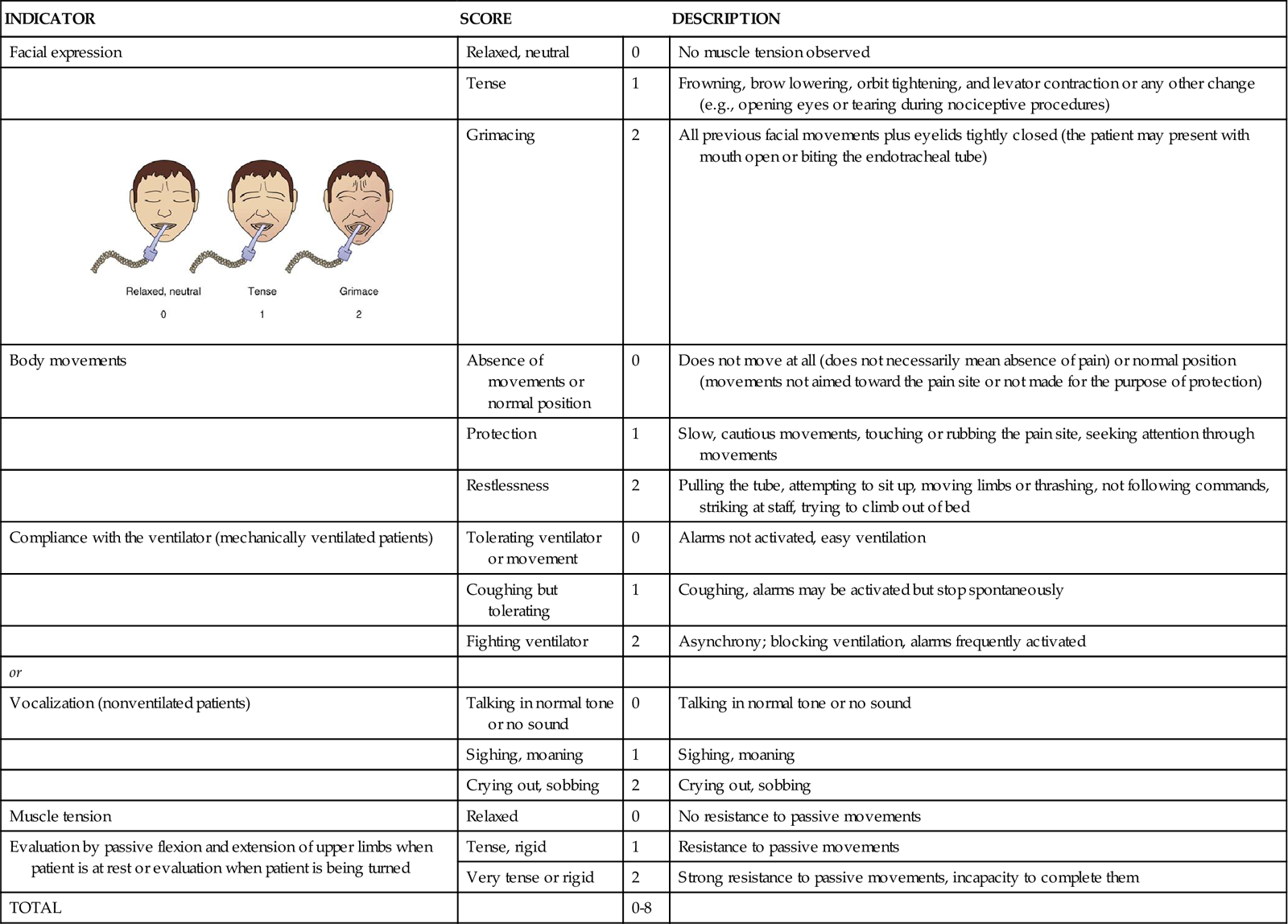

Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool

The CPOT shown in Table 8-2 was tested in verbal and nonverbal critically ill adult patients.19,59 Content validity was supported by ICU expert clinicians, including nurses and physicians.65 Validity of the CPOT was supported with significantly higher CPOT scores during a nociceptive procedure (e.g., turning with or without other care) compared with rest or a nonnociceptive procedure (e.g., taking blood pressure). Significant positive associations were also found between the CPOT scores and the patient’s self-report of pain (the gold standard).66 Feasibility of the CPOT was positively evaluated by ICU nurses.67 Nurses agreed that the CPOT was quick enough to be used in the ICU, simple to understand, easy to complete, and helpful for nursing practice. The CPOT identifies patients with severe pain very well. For patients with moderate to severe pain, the cutoff seems to be between 2 and 3, depending on the patient’s condition.68 Head injury patients seemed to react differently to the nociceptive procedure.19 They were less likely to show frowning, brow lowering, and grimacing. Compared with other patients, a higher proportion of head injury patients showed tearing and open eyes when exposed to the nociceptive procedure.58

TABLE 8-2

CRITICAL CARE PAIN OBSERVATION TOOL (CPOT)

| INDICATOR | SCORE | DESCRIPTION | |

| Facial expression | Relaxed, neutral | 0 | No muscle tension observed |

| Tense | 1 | Frowning, brow lowering, orbit tightening, and levator contraction or any other change (e.g., opening eyes or tearing during nociceptive procedures) | |

|

Grimacing | 2 | All previous facial movements plus eyelids tightly closed (the patient may present with mouth open or biting the endotracheal tube) |

| Body movements | Absence of movements or normal position | 0 | Does not move at all (does not necessarily mean absence of pain) or normal position (movements not aimed toward the pain site or not made for the purpose of protection) |

| Protection | 1 | Slow, cautious movements, touching or rubbing the pain site, seeking attention through movements | |

| Restlessness | 2 | Pulling the tube, attempting to sit up, moving limbs or thrashing, not following commands, striking at staff, trying to climb out of bed | |

| Compliance with the ventilator (mechanically ventilated patients) | Tolerating ventilator or movement | 0 | Alarms not activated, easy ventilation |

| Coughing but tolerating | 1 | Coughing, alarms may be activated but stop spontaneously | |

| Fighting ventilator | 2 | Asynchrony; blocking ventilation, alarms frequently activated | |

| or | |||

| Vocalization (nonventilated patients) | Talking in normal tone or no sound | 0 | Talking in normal tone or no sound |

| Sighing, moaning | 1 | Sighing, moaning | |

| Crying out, sobbing | 2 | Crying out, sobbing | |

| Muscle tension | Relaxed | 0 | No resistance to passive movements |

| Evaluation by passive flexion and extension of upper limbs when patient is at rest or evaluation when patient is being turned | Tense, rigid | 1 | Resistance to passive movements |

| Very tense or rigid | 2 | Strong resistance to passive movements, incapacity to complete them | |

| TOTAL | 0-8 | ||

1 The patient is observed at rest for 1 minute to obtain a baseline value of the CPOT.

6 The patient is given a score for each behavior included in the CPOT.

Modified from Gélinas C, et al: Validation of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool in Adult Patients, Am J Crit Care, 15(4):420, 2006. Figure courtesy Caroline Arbour, RN, BSc, PhD-student, McGill University, Canada.

Behaviors represent valid information for pain assessment in the critically ill patient, but they present some limitations. They are impossible to monitor in paralyzed patients receiving neuromuscular blocking agents, and their presence may be blurred by the use of high doses of sedative agents such as propofol or midazolam.19 Minimal behavioral responses to painful procedures were found in unconscious mechanically ventilated ICU adults who were more heavily sedated compared with conscious patients.58 Similar results were found in previous studies in which patients who received a higher dose of midazolam obtained a lower score on the BPS.45,64 In those difficult situations, the only possible clues left for the detection of pain are physiological indicators.

Physiological Indicators

Physiological vital signs as indicators of pain have received little attention in critically ill adults. Although vital sign values generally increase during painful procedures,19,45,58,64 they are not consistently related to the patient’s self-report of pain, nor are they predictive of pain.19,58 None of the monitored vital signs (heart rate, mean arterial pressure [MAP], respiratory rate, transcutaneous oxygen saturation [SpO2], or end-tidal CO2) predicted the presence of pain in ICU patients.58

The ASPMN recommendations emphasize that vital signs should not be considered as primary indicators of pain because they can be attributed to other distress conditions, homeostatic changes, and medications.21 Changes in vital signs should rather be considered a cue to begin further assessment of pain or other stressors.

Fifth Vital Sign

Because pain is considered the fifth vital sign, including pain assessment with other routinely documented vital signs ensures that pain level is assessed in all patients on a regular basis. This approach can ensure that pain is detected and treatment implemented before the patient develops complications associated with unrelieved pain. The use of a pain flow sheet incorporated into the critical care documentation allows for visible and ongoing pain assessment before and after an intervention for pain that is accessible to all clinicians involved in the assessment and management of pain.69,70

Patient Barriers to Pain Assessment and Management

Communication

The most obvious patient barrier to the assessment of pain in the critical care population is the inability to communicate. Patients who are mechanically ventilated cannot verbalize their pain. If the patient can communicate by head nodding or pointing, pain can be reported in that manner. If writing is possible, the patient may be able to describe the pain. With nonverbal patients, the nurse relies on behavioral clues to assess pain.

The patient’s family can contribute significantly in the assessment of pain. The family is intimately familiar with the patient’s normal responses to pain and can assist the nurse in identifying clues. A family member’s impression of a patient’s pain should be considered in the pain assessment process of the critically ill patient.21

Altered Level of Consciousness

The unconscious patient presents a dilemma for all clinicians. Because pain relies on cortical response to provide recognition, the belief may persist that the patient without higher cortical function has no perception of pain. Interviews by Lawrence71 with 100 patients, who recalled their experiences from a time when they were unconscious in critical care, revealed that they could hear, understand, and respond emotionally to what was being said. Experts recommend assuming that unconscious patients have pain and treating them the same way as conscious patients are treated when they are exposed to sources of pain.21

Studies19,45 have demonstrated that behavioral and physiological indicators of pain can be observed in reaction to a painful procedure in critically ill patients, no matter what their level of consciousness. Knowing this, the critical care nurse can initiate a discussion with the other members of the health care team to formulate a plan of care for the patient’s comfort.

Older Patients

Many older patients do not complain about pain. Some misconceptions, such as believing that pain is a normal consequence of aging or being afraid to disturb the health care team, are barriers to pain expression for the older adult.30 Cognitive deficits or delirium present additional pain assessment barriers. Many older patients with mild to moderate cognitive impairments and even some with severe impairment are able to use pain intensity scales.72,73 Vertical pain intensity scales are more easily understood by this group of patients and are recommended74 (see Figure 8-3). Older patients with cognitive deficits should receive repeated instructions and be given sufficient time to respond.28 When the self-report of pain is impossible to obtain, direct observation of pain-related behaviors is highly recommended in this population.21,73 More than 24 behavioral tools have been developed for older patients with cognitive deficits.72,75,76 The Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC)77 and Doloplus-278,79 are promising tools for use with older adults.73,75,76

Delirium is a form of transient cognitive impairment that is highly prevalent among older patients in the ICU.80 A major challenge with delirium is that there is overlap between delirium behaviors and pain-related behaviors. Pain is recognized as a potentially modifiable contributor to delirium management.81

Cultural Influences

Cultural influences are compounded when the patient speaks a language other than that of the health team members.82 Additionally, differences in pain reporting may exist. To facilitate communication, the use of a pain intensity scale in the patient’s language is vital. The 0 to 10 numeric pain scales have been translated into many different languages.30

Some cultures believe that God’s test or punishment takes the form of pain. Persons with these cultural backgrounds do not necessarily believe that the pain should be relieved. Other cultures perceive pain as being associated with an imbalance in life. Persons from these cultures believe they need to manipulate the environment to restore balance to control pain.82

Lack of Knowledge

A relatively overlooked patient barrier to accurate pain assessment is the public knowledge deficit regarding pain and pain management. Many patients and their families are frightened by the risk of addiction to pain medication. They fear that addiction will occur if the patient is medicated frequently or with sufficient amounts of opiates necessary to relieve the pain. This concern is so powerful for some that they will deny or deliberately underreport the frequency or intensity of pain. Another misconception is the expectation that unrelieved pain is simply part of a critical illness or procedure.83 Many patients have no memory of receiving an explanation of a pain management plan.84 With this in mind, it is important to teach the family and the patient about the importance of pain control and the use of opioids in treating pain in critical illness.

Health Professional Barriers to Pain Assessment and Management

The health professional’s beliefs and attitudes about pain and pain management are frequently a barrier to accurate and adequate pain assessment. Misconceptions or lack of knowledge regarding addiction, physiological dependence, drug tolerance, and respiratory depression remain.

Addiction and Tolerance

Addiction is defined by a pattern of compulsive drug use that is characterized by an incessant longing for an opioid and the need to use it for effects other than pain relief.

Tolerance is defined as a diminution of opioid effects over time. Physical dependence and tolerance to opioids may develop if the drug is given over a long period. Physical dependence is manifested by withdrawal symptoms when the opioid is abruptly stopped. If this is an anticipated problem, withdrawal may be avoided by weaning the patient from the opioid slowly to allow the brain to reestablish neurochemical balance in the absence of the opioid.30

Respiratory Depression

Another concern for health care professionals is the fear that aggressive management of pain with opioids causes respiratory depression. The incidence of respiratory depression in the critically ill is less than 2%.85

Pain Management

The management of pain in the critically ill patient is as multidimensional as the assessment. It is a multidisciplinary task. The control of pain can be pharmacological, nonpharmacological, and ideally a combination of the two therapies.

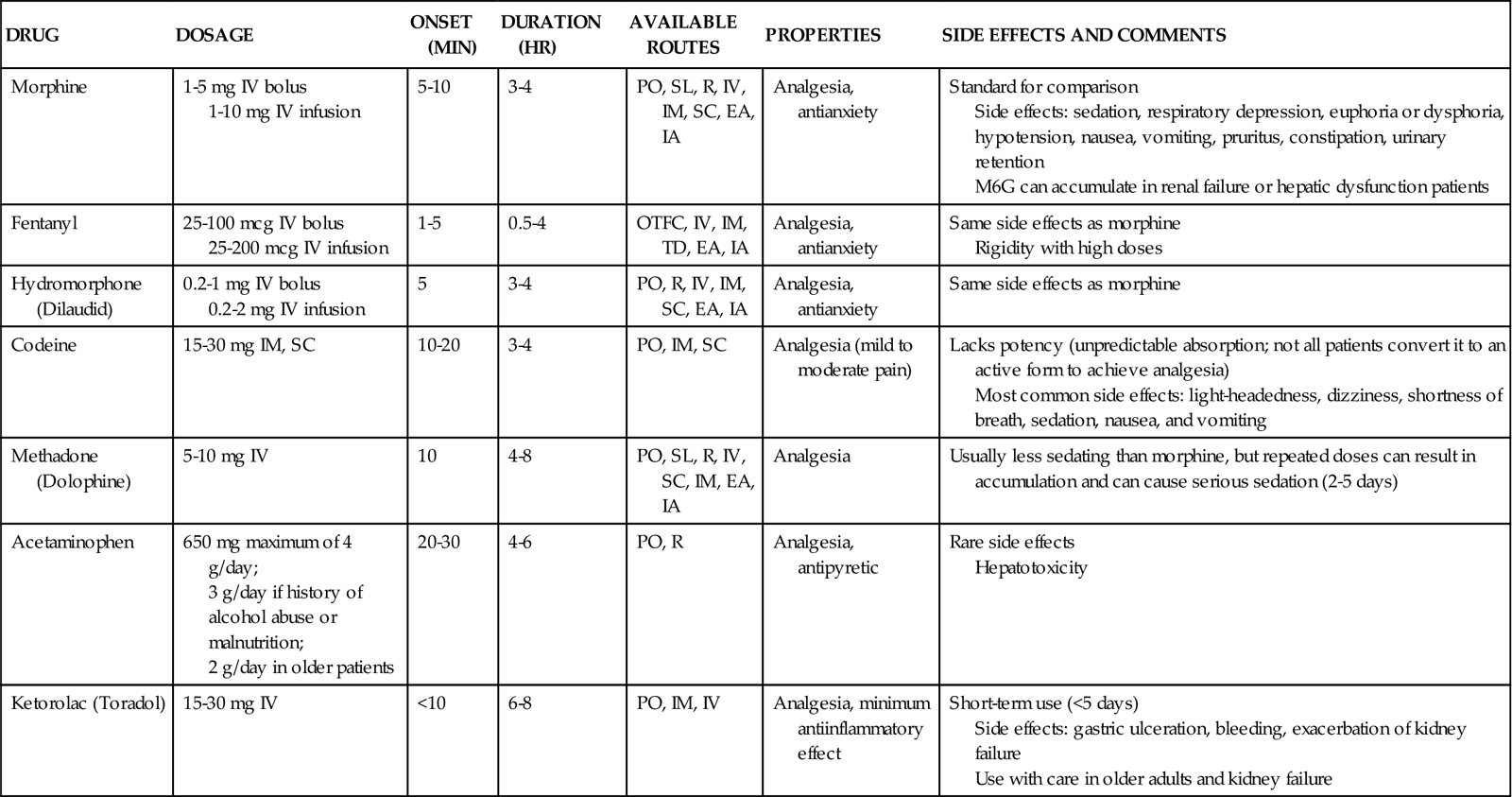

Pharmacological Control of Pain

Pharmacological management of pain has infinite variety in the critical care unit. Pain pharmacology is divided into three categories of action: opioid agonists (morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, meperidine, codeine, methadone, and more potent drugs), nonopioids (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), and adjuvants such as anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and local anesthetics. Elements of the 2002 clinical guidelines22 of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) for pharmacological interventions in the critically ill adult are presented for each opiate discussed (updates to these guidelines are in the process of revision). The algorithm from the current SCCM guidelines for sedation and analgesia management is shown in Figure 10-1 in Chapter 10. How pain is approached and managed is a progression or combination of the available agents, the type of pain, and the patient response to the therapy. Figure 8-4 illustrates the analgesic action sites in relation to nociception.

CNS, central nervous system. (From Melzack R: Pain and stress: a new perspective. In Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, editors: Psychological factors in pain, p 98, New York, 1999, Guilford Press.)

Opioid Analgesics

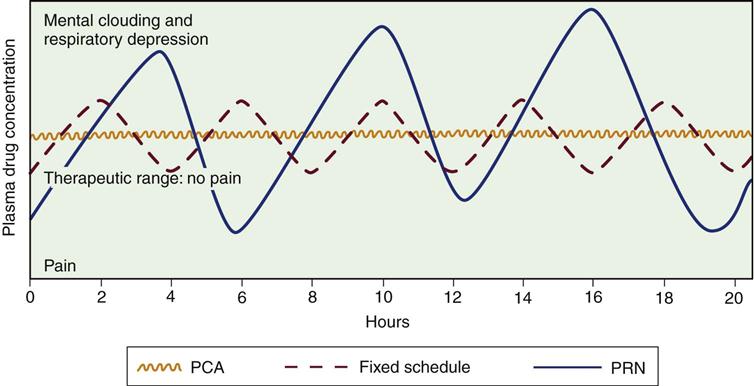

The opioids most commonly used and recommended as first-line analgesics are the agonists. These opioids bind to mu (µ) receptors (transmission process; Figure 8-5), which appear to be responsible for pain relief. Additional pharmacological information is presented in Table 8-3 and Box 8-1. In the SCCM guidelines, scheduled opioid doses or a continuous infusion is preferred over an as-needed regimen to ensure consistent analgesia in critically ill patients.22

PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PRN, as required. (From Lehne RA: Pharmacology for nursing care, ed 5, St Louis, 2004, Saunders.)

TABLE 8-3

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT: PAIN

| DRUG | DOSAGE | ONSET (MIN) | DURATION (HR) | AVAILABLE ROUTES | PROPERTIES | SIDE EFFECTS AND COMMENTS |

| Morphine | 1-5 mg IV bolus 1-10 mg IV infusion |

5-10 | 3-4 | PO, SL, R, IV, IM, SC, EA, IA | Analgesia, antianxiety | Standard for comparison Side effects: sedation, respiratory depression, euphoria or dysphoria, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, constipation, urinary retention M6G can accumulate in renal failure or hepatic dysfunction patients |

| Fentanyl | 25-100 mcg IV bolus 25-200 mcg IV infusion |

1-5 | 0.5-4 | OTFC, IV, IM, TD, EA, IA | Analgesia, antianxiety | Same side effects as morphine Rigidity with high doses |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 0.2-1 mg IV bolus 0.2-2 mg IV infusion |

5 | 3-4 | PO, R, IV, IM, SC, EA, IA | Analgesia, antianxiety | Same side effects as morphine |

| Codeine | 15-30 mg IM, SC | 10-20 | 3-4 | PO, IM, SC | Analgesia (mild to moderate pain) | Lacks potency (unpredictable absorption; not all patients convert it to an active form to achieve analgesia) Most common side effects: light-headedness, dizziness, shortness of breath, sedation, nausea, and vomiting |

| Methadone (Dolophine) | 5-10 mg IV | 10 | 4-8 | PO, SL, R, IV, SC, IM, EA, IA | Analgesia | Usually less sedating than morphine, but repeated doses can result in accumulation and can cause serious sedation (2-5 days) |

| Acetaminophen | 650 mg maximum of 4 g/day; 3 g/day if history of alcohol abuse or malnutrition; 2 g/day in older patients |

20-30 | 4-6 | PO, R | Analgesia, antipyretic | Rare side effects Hepatotoxicity |

| Ketorolac (Toradol) | 15-30 mg IV | <10 | 6-8 | PO, IM, IV | Analgesia, minimum antiinflammatory effect | Short-term use (<5 days) Side effects: gastric ulceration, bleeding, exacerbation of kidney failure Use with care in older adults and kidney failure |

Morphine

Morphine is the most commonly prescribed opioid in the critical care unit. Because of its water solubility, morphine has a slower onset of action and a longer duration compared with lipid-soluble opioids (e.g., fentanyl). This makes morphine and hydromorphone the preferred opioids for intermittent therapy in the SCCM guidelines.22 Morphine has two main metabolites: morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G, inactive) and morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G, active). M6G is responsible for the analgesic effect but may accumulate and cause excessive sedation in patients with kidney failure or liver failure.86 Morphine is available in a variety of delivery methods. It is the standard by which all other opioids are measured. It is also the agent that most closely mimics the endogenous opioids in the human pain modification system.

Morphine is indicated for severe pain. It has additional actions that are helpful for managing other symptoms. Morphine dilates peripheral veins and arteries, making it useful in reducing myocardial workload. Morphine is also viewed as an anti-anxiety agent because of the calming effect it produces.

Many side effects have been reported with the use of morphine (see Table 8-3 and Morphine Priority Medications Box). The hypotensive effect can be particularly problematic in the hypovolemic patient. The vasodilation effect is potentiated in the volume-depleted patient, and the hemodynamic status must be carefully monitored. Volume resuscitation restores blood pressure in the event of a prolonged hypotensive response.

A more serious side effect requiring diligent monitoring is the respiratory depressant effect. Opioids may cause this complication because they reduce the responsiveness of carbon dioxide chemoreceptors in the respiratory center located in the medulla in the brainstem.87 Although infrequent, this effect can have significant sequelae for the critically ill patient. A subset of patients is at greater risk for respiratory depression after opioid administration. This subset includes newborns (younger than 6 months), older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or known obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, patients who are opiate naïve (receiving opiates for less than a week), and patients with kidney failure.85 Critical care nurses must monitor these patients intensively to prevent this complication. Monitoring of patients receiving opioid analgesics is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. In addition to side effects common to all opioids, morphine may stimulate histamine release from mast cells, resulting in cardiac instability and allergic reactions.

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid preferred for critically ill patients with hemodynamic instability or morphine allergy. It is a lipid-soluble agent that has a more rapid onset than morphine and a shorter duration.86 The metabolites of fentanyl are largely inactive and nontoxic, which makes it an effective and safe opioid. However, repeated doses may cause accumulation and prolonged effects of the drug. The use of fentanyl in the critical care unit is growing in popularity, and it is the preferred agent for acutely distressed patients, hemodynamically unstable patients, and for those with impaired kidney function22 (see Table 8-3 and Fentanyl Priority Medications Box). Fentanyl is available in intravenous, intraspinal, and transdermal forms. The transdermal form is commonly referred to as the Duragesic patch or the 72-hour patch.

Because the side effects of fentanyl are similar to those of morphine, the nurse must monitor carefully the hemodynamic and respiratory responses. When fentanyl is given by rapid administration and at higher doses, it has been associated with the additional hazard of bradycardia and rigidity in the chest wall muscles.22,86 The use of transdermal fentanyl is indicated rarely in the acutely critically ill patient. The customary use of the “fentanyl patch” is for those experiencing chronic pain or cancer pain, and in critical care it is used for patients who require extended pain control. Transdermal delivery requires 12 to 16 hours for onset of action, and the patch duration is 72 hours.30 If the transdermal delivery method is used, the patient will require concurrent opioid management until the fentanyl patch takes effect.

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone is a semisynthetic opioid that has an onset of action and duration similar to those of morphine.86 It is an effective opioid with multiple routes of delivery. It is more potent than morphine. Hydromorphone is a safe choice in patients with kidney failure as it lacks active metabolites.22 Also, it has been shown that some side effects (e.g., pruritus, sedation, nausea, vomiting) may occur less with hydromorphone than morphine87 (see Table 8-3).

Meperidine

Meperidine (Demerol) is a less potent opioid with agonist effects similar to those of morphine. It is considered the weakest of the opioids, and it must be administered in large doses to be equivalent in action to morphine. Because the duration of action is short, dosing is frequent. A major concern with this drug is the metabolite normeperidine, which is a CNS neurotoxic agent. At high doses in patients with kidney failure or liver dysfunction or in older patients, it may induce CNS toxicities, including irritability, muscle spasticity, tremors, agitation, and seizures.30 Research has shown that meperidine can cause delirium in postoperative patients of all ages.88 Although meperidine is useful in short-term specific conditions (e.g., treating postoperative shivering), it should be avoided in patients who require longer periods of analgesia and is not recommended for repetitive use.22

Codeine

Codeine has limited use in the management of severe pain. It is rarely used in the critical care unit. It provides analgesia for mild to moderate pain. It is usually compounded with a nonopioid (e.g., acetaminophen). To be active, codeine must be metabolized in the liver to morphine.30 Codeine is available only through oral, intramuscular, and subcutaneous routes, and its absorption can be reduced in the critical care patient by altered gastrointestinal motility and decreased tissue perfusion.89

Methadone

Methadone is a synthetic opioid with morphine-like properties that causes less sedation. It is longer acting than morphine and has a long half-life. This makes it difficult to titrate in the critical care patient. Methadone lacks active metabolites, and routes other than the kidney eliminate 60% of the drug. This means that methadone does not accumulate in patients with kidney failure.90 Methadone is recommended as a second-line opioid analgesic.91 It may be a good alternative for the patient who has a long recovery ahead with an anticipated prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation.86

More Potent Opioids: Remifentanil and Sufentanil

Remifentanil and sufentanil are agonist opioids. The use of these potent drugs has been studied in critically ill patients.

Remifentanil is 250 times more potent than morphine, and it has a rapid onset and predictable offset of action. For this reason, it allows a rapid emergence from sedation, facilitating the evaluation of the neurological state of the patient after stopping the infusion.92,93

Sufentanil is 7 to 13 times more potent than fentanyl and 500 to 1000 times more potent than morphine. It has more pronounced sedation properties than fentanyl and other opioids. Patients under sufentanil require minimal sedative agent doses to achieve an adequate sedation level. It has a rapid distribution and a high clearance rate, preventing accumulation when given for a long period.94 Sufentanil has a longer emergence from sedation compared with remifentanil, but it allows a longer analgesic effect after stopping its administration.93

Preventing and Treating Respiratory Depression

Respiratory depression is the most life-threatening opioid side effect. The risk of respiratory depression increases when other drugs with CNS depressant effects (e.g., benzodiazepines, antiemetics, neuroleptics, antihistamines) are concomitantly administered to the patient.86 Respiratory depression is defined as a decrease in the rate or depth of respirations, not necessarily a specific number of respirations per minute. Respiratory rates less than 8 or 10 require rapid assessment. A change in the patient’s level of consciousness or an increase in sedation normally precedes respiratory depression.

Monitoring

Patients should be monitored before the administration of the opioid agent and at its peak effect. Monitoring for the following parameters at least every 1 to 2 hours for the first 24 hours and every 4 hours thereafter in stable patients95,96 is recommended to prevent respiratory depression:

• Pain intensity, using a valid pain scale

• Sedation level, using a valid sedation scale (see Chapter 9, Table 9-1)

Monitoring oxygen saturation (SpO2) is recommended to detect deterioration in respiratory condition.97 The use of capnography, which is available in many critical care settings, should be considered for non-intubated high-risk patients receiving opiate parenteral therapy.96

Opioid Reversal

Critical respiratory depression can be readily reversed with the administration of the opiate antagonist naloxone (Narcan). The usual dose is 0.4 mg, mixed with 10 mL of normal saline98 (for a concentration of 0.04 mg/mL). Naloxone is administered intravenously (IV), very slowly, and can be discontinued as soon as the patient is responsive to physical stimulation and able to take deep breaths. Because the duration of naloxone is shorter than most opioids, another dose of naloxone may be needed as early as 30 minutes after the first dose. The nurse monitors sedation and respiratory status and frequently reminds the patient to breathe deeply. The benefits of reversing respiratory depression with naloxone must be weighed against the risk of sudden onset of pain and the difficulty of achieving pain relief. To prevent this from occurring, it is important to provide a nonopioid medication for pain management.98 Moreover, the use of naloxone is not recommended after prolonged analgesia, because it can induce withdrawal and may cause nausea and cardiovascular complications (e.g., dysrhythmias).22

Nonopioid Analgesics

In the SCCM guidelines, the use of nonopioids in combination with an opioid is recommended in selected critical care patients.22 The goal is to reduce opioid requirements and provide greater analgesic effect through peripheral and central levels.23 Pharmacological information is presented in Table 8-3.

Delivery Methods

The most common route for drug administration is IV by means of continuous infusion, bolus administration, or patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). Traditionally, the choice has been IV bolus administration. The benefits of this method are the rapid onset of action and the ease of titration. The major disadvantage is the rise and fall of the serum level of the opioid, leading to periods of pain control with periods of breakthrough pain99 (see Figure 8-5).

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is a method of drug delivery that uses the intravenous route and an infusion pump. It allows the patient to self-administer small doses of analgesics. Different opioids can be used, but the most extensively used is morphine.99 This method of medication delivery allows self-administration of a medication bolus the moment the pain begins (see Figure 8-5). Naloxone must be readily available to reverse adverse opiate respiratory effects. Ideally, the patient undergoing an elective procedure requiring opioid analgesia postoperatively is instructed in the use of PCA during preoperative teaching. This allows the patient to become comfortable with the concept of self-medication before use.

Intraspinal anesthesia uses the concept that the spinal cord is the primary link in nociceptive transmission. The goal is to mimic the body’s endogenous opioid pain modification system by interfering with the transmission of pain and providing an opiate receptor-binding agent directly into the spinal cord. The benefits of the intraspinal route include good to excellent pain control with typically lower doses of opioids, increased patient mobility, minimal sedation, and increased patient satisfaction.100 The hemodynamic status of the patient changes very little.

Intraspinal anesthesia is particularly appropriate for pain in the thorax, upper abdomen, and lower extremities. The two intraspinal routes are intrathecal and epidural. Regardless of the route, the effects of the opioid agonist used are the same, and assessment parameters are the same as those used for other routes.

Intrathecal Analgesia

Intrathecal (subarachnoid) opioids are placed directly into the cerebral spinal fluid and attach to spinal cord receptor sites. Opioids introduced at this site act quickly at the dorsal horn. The dural sheath is punctured, eliminating the barrier for pathogens between the environment and the cerebral spinal fluid. This creates the risk of serious infections. The intrathecal route is usually reserved for intraoperative use. Single-bolus dosing provides short-term relief for pain that is short lived (the pain of labor and delivery is well managed using this regimen. Side effects of intrathecal pain control include postdural puncture headache and infection.101

Epidural Analgesia

Epidural analgesia is commonly used in the critical care unit after major abdominal surgery, nephrectomy, thoracotomy, and major orthopedic procedures. Certain conditions preclude the use of this pain control method: systemic infection, anticoagulation, and increased intracranial pressure. Epidural delivery of opiates provides longer-lasting pain relief with less dosing of opiates. When delivered into the epidural space, 5 mg of morphine may be effective for 6 to 24 hours, compared with 3 to 4 hours when delivered intravenously. Opioids infused in the epidural space are more unpredictable than those administered intrathecally. The epidural space is filled with fatty tissue and is external to the dura mater. The fatty tissue interferes with uptake, and the dura acts as a barrier to diffusion, making diffusion rate difficult to predict.

The type of drug used determines the rapidity of drug diffusion. Drugs are hydrophilic or lipophilic. Hydrophilic drugs like morphine are water-soluble and penetrate the dura slowly, giving them a longer onset and duration of action. Lipophilic drugs including fentanyl are lipid-soluble; they penetrate the dura rapidly and therefore have a rapid onset of action and a shorter duration of action.

The dura acts as a physical barrier and causes delay in diffusion of the drug. Compared with the intrathecal route, it allows more of the drug to be absorbed in the systemic circulation, requiring greater doses for pain relief.100 Drugs delivered epidurally may be administered by bolus or continuous infusion. Epidural analgesia is being used more often in the critical care environment, and it requires careful monitoring.

The nurse must assess the patient for respiratory depression. This phenomenon may occur early in the therapy or as late as 24 hours after initiation. The epidural catheter also puts the patient at risk for infection. The efficiency of this pain control method, and the patient’s increased mobility, do not diminish the nurse’s responsibility to monitor and evaluate the outcomes of the pain-management protocol in use.

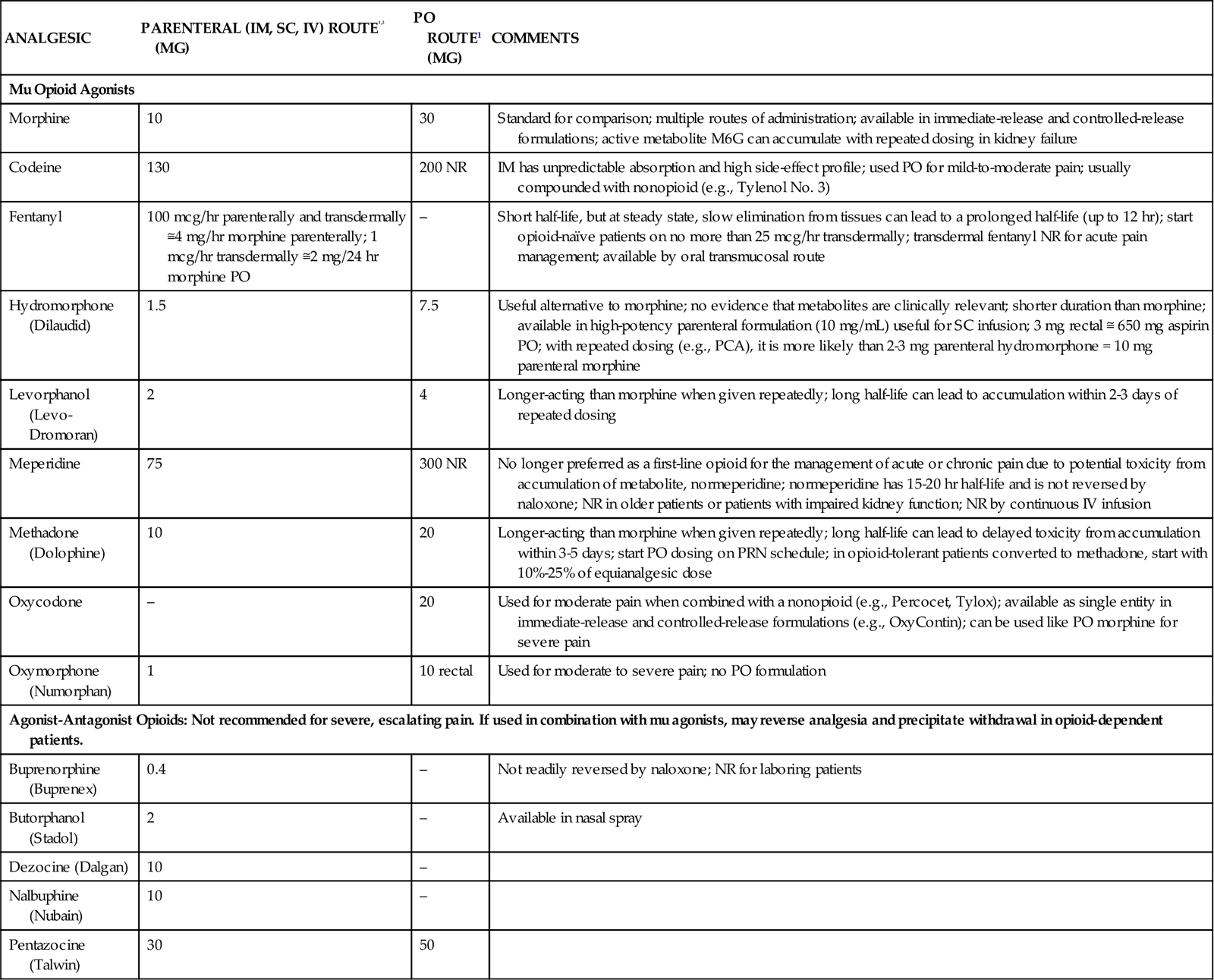

Equianalgesia

When a change of opioid is considered, the nurse must be aware of equianalgesic dosages. In doing any conversion, the goal is to provide equal analgesic effects with the new agents. This concept is referred to as equianalgesia. Morphine is the standard for the conversion of opioids. Prescribed dosages must take into account the patient’s age and health status.30 Because of the variety of agents and routes, the professional pain organizations have developed equianalgesia charts for use by health care professionals. All critical care units need a chart posted for easy referral. Table 8-4 provides the equianalgesia dose for different drugs used in clinical practice.

TABLE 8-4

EQUIANALGESIC CHART: APPROXIMATE EQUIVALENT DOSES OF OPIOIDS FOR MODERATE-TO-SEVERE PAIN

| ANALGESIC | PARENTERAL (IM, SC, IV) ROUTE1,2 (MG) | PO ROUTE1 (MG) | COMMENTS |

| Mu Opioid Agonists | |||

| Morphine | 10 | 30 | Standard for comparison; multiple routes of administration; available in immediate-release and controlled-release formulations; active metabolite M6G can accumulate with repeated dosing in kidney failure |

| Codeine | 130 | 200 NR | IM has unpredictable absorption and high side-effect profile; used PO for mild-to-moderate pain; usually compounded with nonopioid (e.g., Tylenol No. 3) |

| Fentanyl | 100 mcg/hr parenterally and transdermally ≅4 mg/hr morphine parenterally; 1 mcg/hr transdermally ≅2 mg/24 hr morphine PO | – | Short half-life, but at steady state, slow elimination from tissues can lead to a prolonged half-life (up to 12 hr); start opioid-naïve patients on no more than 25 mcg/hr transdermally; transdermal fentanyl NR for acute pain management; available by oral transmucosal route |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) | 1.5 | 7.5 | Useful alternative to morphine; no evidence that metabolites are clinically relevant; shorter duration than morphine; available in high-potency parenteral formulation (10 mg/mL) useful for SC infusion; 3 mg rectal ≅ 650 mg aspirin PO; with repeated dosing (e.g., PCA), it is more likely than 2-3 mg parenteral hydromorphone = 10 mg parenteral morphine |

| Levorphanol (Levo-Dromoran) | 2 | 4 | Longer-acting than morphine when given repeatedly; long half-life can lead to accumulation within 2-3 days of repeated dosing |

| Meperidine | 75 | 300 NR | No longer preferred as a first-line opioid for the management of acute or chronic pain due to potential toxicity from accumulation of metabolite, normeperidine; normeperidine has 15-20 hr half-life and is not reversed by naloxone; NR in older patients or patients with impaired kidney function; NR by continuous IV infusion |

| Methadone (Dolophine) | 10 | 20 | Longer-acting than morphine when given repeatedly; long half-life can lead to delayed toxicity from accumulation within 3-5 days; start PO dosing on PRN schedule; in opioid-tolerant patients converted to methadone, start with 10%-25% of equianalgesic dose |

| Oxycodone | – | 20 | Used for moderate pain when combined with a nonopioid (e.g., Percocet, Tylox); available as single entity in immediate-release and controlled-release formulations (e.g., OxyContin); can be used like PO morphine for severe pain |

| Oxymorphone (Numorphan) | 1 | 10 rectal | Used for moderate to severe pain; no PO formulation |

| Agonist-Antagonist Opioids: Not recommended for severe, escalating pain. If used in combination with mu agonists, may reverse analgesia and precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients. | |||

| Buprenorphine (Buprenex) | 0.4 | – | Not readily reversed by naloxone; NR for laboring patients |

| Butorphanol (Stadol) | 2 | – | Available in nasal spray |

| Dezocine (Dalgan) | 10 | – | |

| Nalbuphine (Nubain) | 10 | – | |

| Pentazocine (Talwin) | 30 | 50 | |

1Duration of analgesia is dose dependent; the higher the dose, usually the longer the duration.

2IV boluses may be used to produce analgesia that lasts approximately as long as IM or SC doses. However, of all routes of administration, IV produces the highest peak concentration of the drug, and the peak concentration is associated with the highest level of toxicity (e.g., sedation). To decrease the peak effect and lower the level of toxicity, IV boluses may be administered more slowly (e.g., 10 mg of morphine over a 15-minute period), or smaller doses may be administered more often (e.g., 5 mg of morphine every 1-1.5 hours).

Data from Pasero, C, & McCaffery, M (2010). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management. Mosby Elsevier: St Louis. Selected references for more information: American Pain Society (APS): Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute and cancer pain, ed 3, Glenview, Ill., 1992, APS; Lawlor P, et al: Dose ratio between morphine and hydromorphone in patients with cancer pain: a retrospective study, Pain 72(1-2):79, 1997; Manfredi PL, et al: Intravenous methadone for cancer pain unrelieved by morphine and hydromorphone: clinical observations, Pain 70(1):99, 1997; Portenoy RK: Opioid analgesics. In Portenoy RK, Kanner RM, editors: Pain management: theory and practice, Philadelphia, 1996, FA Davis.

Nonpharmacological Methods of Pain Management

Although numerous methods of pain management other than drugs appear in critical care literature,102 very few studies have been done to provide evidence of their effectiveness in the critical care settings. Nonpharmacological methods can be used to supplement analgesic treatment, but they are not intended to replace analgesics.103 In most instances, these therapies may augment and enhance the pharmacological management of the patient’s pain. Critical care nurses identify many barriers to use of nonpharmacological methods for pain management, including lack of knowledge, training, and time.104

Cognitive Techniques

Cognitive techniques include patient teaching, relaxation, distraction, guided imagery, and music therapy.

Relaxation

Relaxation is a well-documented method for reducing the distress associated with pain. Although not a substitute for pharmacology, relaxation is an excellent adjunct for controlling pain.105,106 Relaxation decreases oxygen consumption and muscle tone, and it can decrease heart rate and blood pressure. Relaxation can give the patient a sense of control over the pain and reduce muscle tension and anxiety. Not all patients are interested in relaxation therapy. For those patients, deep-breathing exercises may be helpful, and they frequently lead to relaxation.107 Excellent references for techniques in relaxation therapy are available.30

Guided Imagery

Guided imagery uses the imagination to provide control over pain. It can be used to distract or relax. Guiding a patient to a place that is pain free and relaxing takes a considerable time commitment on the part of the nurse. Although this may be difficult in the critical care environment, guiding patients to a place in their imagination that is free from pain may be beneficial.102

Music Therapy

Music therapy is a commonly used intervention for relaxation. Music that is pleasing to the patient may have soothing effects, but its effects on reducing pain are controversial.108 Ideally, the music should be supplied by a small set of headphones. It is important to educate the patient and family regarding the role of music in relaxation and pain control and to provide music of the patient’s choice. The patient and family may also provide information about sources of distraction for the patient. Some persons are distracted by television; for others, television may increase anxiety.

The key to success with pain management in critically ill patients is a comprehensive understanding of effective pain assessment methods and drug mechanisms of action so that the therapy matches the needs of the patient. In addition, when used effectively, nonpharmacological options such as relaxation and music therapy may assist with pain management in critical illness.