Groin pain

Introduction

Groin injuries tax the diagnostic and therapeutic abilities of the clinician.1,2 Although they are considered to be common and the most frequent overuse syndromes in some athletic activities such as soccer,3 they are difficult to manage correctly.

History

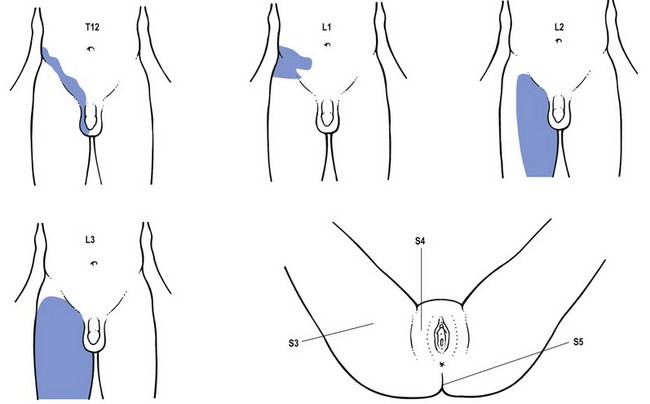

The clinician confronted with the prospect of evaluating a patient who complains of groin pain should first of all ask the patient to point to the pain and also establish whether it is localized or diffuse. The groin area is not only the crossing site of trunk and lower extremity muscles but is also a region of considerable dermatomical overlap which includes T11, T12, L1, L2, L3 and S4 (Fig. 1). Pain in the groin can also be of extrasegmental origin.

Once the localization and any radiation of the pain have been clarified, the examiner continues with the routine history which relates to problems in the back, sacroiliac region and the hip (see Ch. 36, 45, 61). Finally questions related to possible intra-abdominal disorders may be indicated. For example:

Interpretation

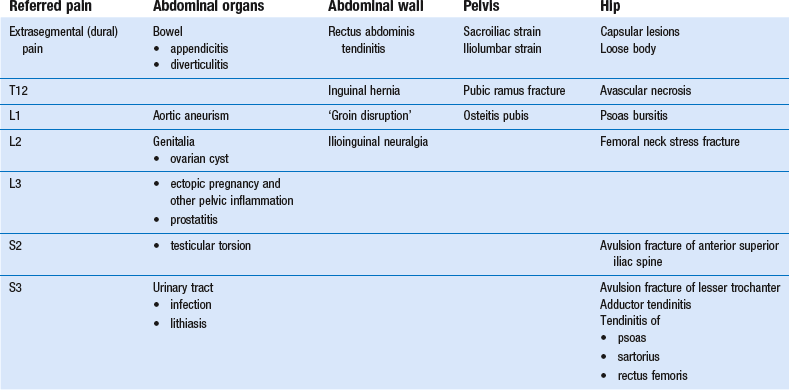

The causes that can result in groin pain are numerous and are summarized in Table 1. Differential diagnosis is not difficult if the guidelines and principles for a good functional examination of the lumbar spine and hip are followed. However, occasionally the results may be confusing. This is usually caused by the fact that resisted movements in and around the groin not only stress the activated contractile structures, but often also induce transmitted stress on inert structures (bones, ligaments). For example, resisted ad- and abduction movements of the hip may indirectly put stress on the sacroiliac or iliolumbar ligaments or on the pubic symphysis.

Femoral neck stress fracture

Examination reveals an antalgic gait. There is usually a discrepancy between the obvious gait and the rather subtle signs on clinical examination: a full range of motion with pain produced at the extremes of hip rotation and on axial compression.4,5

Early radiographs may be negative and absence of a fracture line does not rule out a stress fracture. A bone scan should be positive 2–8 days after symptoms appear. Further imaging studies such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be undertaken early if clinical suspicion warrants it.6

Treatment is based on the type of fracture. If the bone scan is positive but there is no visible fracture on plain film, initial treatment will consist of modified bed rest. This leads on to non-weight bearing with crutches and then pain-free weight bearing.3 If there is visible fracture on the plain film, open reduction and internal fixation is the treatment of choice because of the high risk of displacement. An already displaced fracture is considered an orthopaedic emergency and requires open reduction and internal fixation.

Acetabular labral tears

Recent arthroscopic studies suggest that most internal derangement in the hip may be the result of impingement of acetabular labral tears.7 The history is that of internal derangement: a feeling of giving way or a sharp ‘twinge’ in the groin that radiates into the anterior thigh, especially with a rotation of the hip while rising from a seated position. On examination, a non-capsular pattern of limitation is found, with limitation of lateral rotation (see p. 642).

Some authors report successful diagnosis of impingement lesions with the so-called Thomas test.3 This involves flexion and external rotation of the hip and then allowing the extremity to abduct. The hip is then moved into extension, internal rotation and adduction. A positive test result is indicated by a palpable or audible click and the production of typical pain. Arthrography, MRI and arthroscopy can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment consists of manipulation (p. 642), although arthroscopic or open operative excision may be necessary in recalcitrant cases.

Pubic ramus stress fracture

Treatment consists of cessation of running activities. Most athletes will show complete union of bone at 3–5 months.3

Osteitis pubis

Although osteitis pubis is a well-known entity following surgery of the bladder or the prostate;8 it has also been reported after athletic endeavours.

Osteitis pubis (an inflammatory lesion of the bone adjacent to the symphysis pubis) in athletes is thought to be the result of mechanical strain from trauma, excessive twisting and turning in sports such as soccer or repetitive shear stress from excessive side-to-side motion.9 It is quite common in ice-hockey players, soccer players and in long-distance runners. It is also frequent in women who exercise in the postpartum period because of the particular instability of the symphysis after birth.10

Complaints develop gradually and the patient cannot link the onset to any known injury. Pain is described as originating from the pubic region, with radiation into the lower abdomen, the groin and the adductor regions. The pain is linked to the athletic activity and gradually disappears upon resting. Coughing or sneezing may be painful.11 In severe examples the athlete may develop an antalgic or waddling gait.

On examination there is a full range of passive movement of the hips with pain elicited by passive abduction and resisted adduction. The fact that the pain is reproduced during the examination of both lower extremities should help in the differentiation from a tendinitis of the adductor longus (p. 654). Palpation also causes pain along the pubic bones and the symphysis itself and not at the tendinous junction of the adductor muscles.

Bone scintigraphy, which typically shows increased uptake unilaterally or bilaterally at the pubic bones, is effective in making an early diagnosis. Radiographic changes may not be visible for 2–3 weeks but then show a symmetric resorption of the medial ends of the pubic bone, widening of the symphysis and rarefaction or sclerosis along the pubic rami. CT scan demonstrates early degenerative changes in the cortical bone, including erosions, cysts and osteophytic spurs at the symphysis.12

Treatment initially includes relative rest because the condition is usually considered as self-limiting within 8–12 weeks. One or two infiltrations with 20 mg triamcinolone into the symphysis may hasten healing.13

Groin hernia

An inguinal hernia is located above and at the medial end of the inguinal ligament. A femoral hernia, more common in female patients, is below and lateral to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 2).

An indirect inguinal hernia is congenital in origin and is caused by a failure of the processus vaginalis of the peritoneum soundly to close. It therefore originates at the internal inguinal ring, appears at the external ring and may extend into the scrotum. The relationship to injury is uncertain and, in contrast to the ‘sports hernia’ described below, many authorities consider that it develops from a weakness or tear of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal more lateral than that in a direct inguinal hernia in the presence of a potentially patent processus vaginalis.14

Examination for both types of inguinal hernia involves invaginating the scrotal skin along the spermatic cord using the index finger in males (Fig. 3) or direct palpation in females. A palpable mass may or may not be detected.

‘Sports hernia’ or ‘groin disruption’

Athletes in fast-moving sports that involve twisting and turning – such as soccer, rugby and ice hockey – may be at particular risk of a tendinous disruption in the area of the inguinal canal.15 This injury, often called a ‘sports hernia’, usually involves the posterior wall of the inguinal canal and can appear as a tear of the transversus abdominis muscle or as a disruption to the conjoined tendon – the tendon of insertion of both the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles (Fig. 4).16 A sports hernia may, however, also involve a lesion of the external oblique aponeurosis and cause a dilatation of the external inguinal ring.17

A sports hernia should be differentiated from the more common inguinal hernia in that it does not involve a clinically detectable hernia (there is not a protrusion of any abdominal tissue through the walls of the abdominal cavity).18 The term ‘disruption’ is therefore more appropriate to describe this type of lesion.

A sports hernia typically produces unilateral groin pain during exercises. In chronic cases, however, the patient may have symptoms during activities of daily living. Onset of pain is usually insidious but may occur suddenly. It is typically localized to the conjoined tendon but can involve the inguinal canal more laterally. Sudden movements often exacerbate the pain.19

Ilioinguinal neuralgia20

The ilioinguinal nerve originates from the Ll–L2 nerve roots. It passes between the ilium and psoas major to perforate the transversus abdominis near the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 5). The nerve pierces the internal oblique, transverses the inguinal canal below the spermatic cord, emerging with it from the superficial inguinal ring to supply the proximomedial skin over the penile root and the scrotum in men or that covering the mons pubis and the adjoining labium majus in women. During its course it innervates the lowest portions of the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles as well as the skin overlying the inguinal ligament.

Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment is a well-established cause of chronic inguinal pain in patients who have had lower abdominal and inguinal hernia surgery (e.g. appendectomy or inguinal herniorrhaphy).21 Direct trauma, intense abdominal muscle training or inflammatory conditions can also lead to entrapment of this nerve as it passes through or close to the abdominal muscle layers.22,23

Treatment consists of three infiltrations at weekly intervals at the confirmed site with 5 ml procaine 0.5 to 1%.24 In severe cases 20 mg triamcinolone may be added to the solution. Nerve ablation may be indicated if the lesion does not respond to infiltrations.

References

1. Renstrom, PA, Tendon and muscle injuries in the groin area. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11(4):815–831. ![]()

2. Jaeger, JH. La pubalagie. In: Catonne Y, Saillant G, eds. Lesions Traumatique des Tendons chez le Portif. Paris: Masson, 1992.

3. Gross, ML, Nasser, S, Finerman, GAM. Hip and pelvis. In: DeLee JC, Drez D, Jr., eds. Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1994:1063–1085.

4. Clough, TM, Femoral neck stress fracture: the importance of clinical suspicion and early review. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(4):308–309. ![]()

5. Gurney, B, Boissonnault, WG, Andrews, R, Differential diagnosis of a femoral neck/head stress fracture. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(2):80–88. ![]()

6. Shin, AY, Morin, WD, Gorman, JD, Jones, SB, Lapinsky, AS, The superiority of magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating the cause of hip pain in endurance athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(2):168–176. ![]()

7. Fitzgerald, RH, Jr., Acetabular labrum tears. Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop. 1995;3(11):60–68. ![]()

8. Seigne, JD, Pisters, LL, von Eschenbach, AC, Osteitis pubis as a complication of prostate cryotherapy. J Urol. 1996;156(1):182. ![]()

9. Fricker, PA, Taunton, JE, Ammann, W, Osteitis pubis in athletes. Infection, inflammation or injury? Sports Med. 1991;12(4):266–279. ![]()

10. Gonik, B, Stringer, CA, Postpartum osteitis pubis. South Med J. 1985;78(2):2l3–4. ![]()

11. Smedberg, SG, Broome, AE, Gullmo, A, Ross, H, Herniography in athletes with groin pain. Am J Surg 1985; 149:378–382. ![]()

12. Holmich, P, Holmich, LR, Bjerg, AM, Clinical examination of athletes with groin pain: an intraobserver and interobserver reliability study. Br J Sports Med 2004; 38:446–451. ![]()

13. Holt, MA, Keene, JS, Graf, BK, Helwig, DC, Treatment of osteitis pubis in athletes. Results of corticosteroid injections. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(5):601–606. ![]()

14. Ruane, JJ, Rossi, TA, When groin pain is more than ‘just a strain’: navigating a broad differential. Phys Sports Med. 1998;26(4):78–103. ![]()

15. Lacroix, VJ, Kinnear, DG, Mulder, DS, Lower abdominal pain syndrome in National Hockey League players: a report of cases. Clin Sports Med. 1998;8(1):5–9. ![]()

16. Gilmore, OJA. Gilmore’s groin: a ten year experience of groin disruption. Sports Med Soft Tissue Trauma. 1991; 3:5–7.

17. Hackney, RG, The ‘sports hernia’: a cause of groin pain. Br J Sports Med. 1993;27(1):58–62. ![]()

18. Lovell, G, The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1995;27(3):76–79. ![]()

19. Kemp, S, Batt, ME, The ‘sports hernia’: a common cause of groin pain. Phys Sports Med. 1998;26(1):36–44. ![]()

20. Starling, JR, Harms, BA, Schroeder, ME, Eichman, PL, Diagnosis and treatment of genitofemoral and ilioinguinal entrapment neuralgia. Surgery. 1987;102(4):581–586. ![]()

21. Monga, M, Ghoniem, GM, Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment following needle bladder suspension procedures. Urology. 1994;44(3):447–450. ![]()

22. Kopell, HP, Thompson, WAL, Postel, AH, Entrapment neuropathy of the ilioinguinal nerve. N Engl J Med 1962; 266:16–19. ![]()

23. Ziprin, P, Williams, P, Foster, ME, External oblique aponeurosis nerve entrapment as a cause of groin pain in the athlete. Br J Surg. 1999;86(4):566–568. ![]()

24. Knockaert, DC, D’Heygere, FG, Bobbaers, HJ, Ilioinguinal nerve entrapment: a little-known cause of iliac fossa pain. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65(767):632–635. ![]()