CHAPTER 36 Overview of Petroclival Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Clivus meningiomas in particular have until recently been uniformly lethal. The outlook for such patients must be improved by achieving an earlier and more accurate diagnosis, by improving surgical techniques, and by developing a better understanding the pathological anatomy.1

Posterior fossa meningiomas account for only 10% to 15% of intracranial meningiomas, and petroclival meningiomas account for only 3% to 10% of posterior fossa meningiomas.1–8 This is consistent with the incidence of 1.7% reported by Cushing and Eisenhardt in their series of 295 meningiomas.2 Owing to their rarity, crucial location, insidious growth, and relentless natural progression toward fatality, clival and petroclival meningiomas remain the most formidable of all meningiomas and the most challenging in the neurosurgical realm. The simple definition of these tumors and accurate characterization has yet to be settled and universally followed.

The natural history of nonoperative patients harboring clival meningiomas is that of relentless progression to an eventually fatal outcome.1–3,9 A review of the early literature shows a cumulating operative mortality that exceeds 50%.1,9,10 Before 1970, only one successful total removal was reported.4 Hence, these tumors were generally considered inoperable.3,11

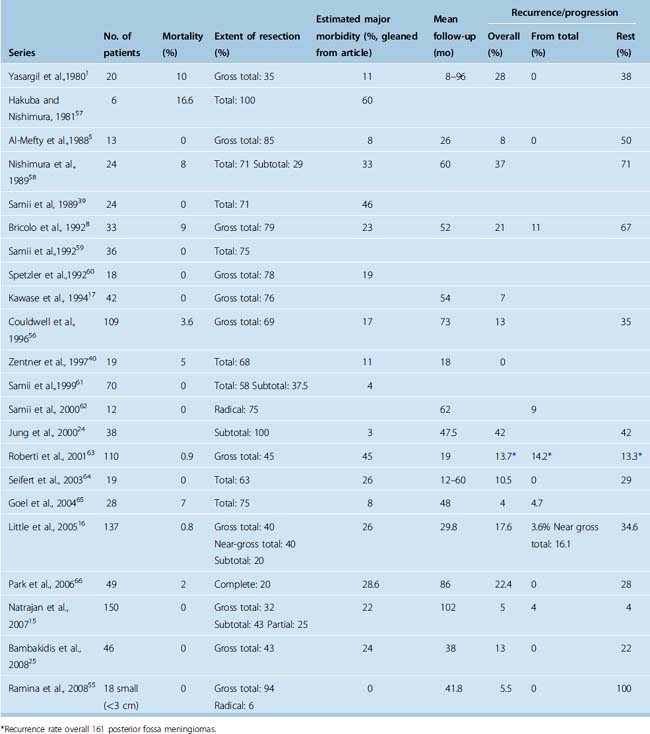

With the advent of refined skull-base approaches, microsurgical techniques, intraoperative monitoring, advanced imaging, and modern anesthesia and postoperative care, the previously dismal surgical outcome has been largely overcome, with reports signifying a major decrease in operating mortality and morbidity, a higher incidence of total removal, and an improved clinical outcome1,5,10,12–17 (Table 36-1). The size of the lesion is a significant factor influencing surgical morbidity and mortality.15,18,19

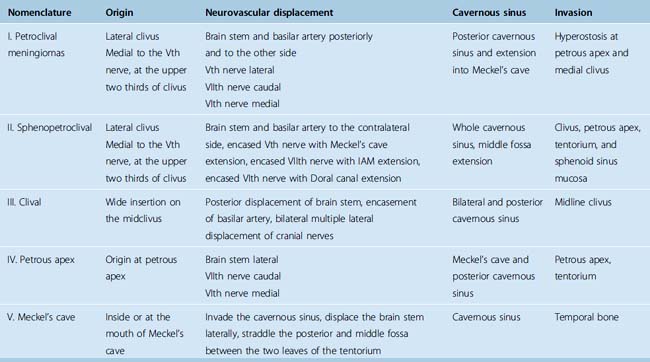

TABLE 36-1 Author’s classification of petroclival meningiomas based on origin and anatomical displacement20

Meningiomas are benign tumors whose treatment objective is total resection. This is best achieved during the first operation when arachnoid membranes are intact, facilitating dissection of neurovascular structures and resection of the tumor.20 The recurrence rate is directly related to the resection grade, with a 89% recurrence rate of meningiomas that were not totally removed.21,22 Although surgeons should pursue total removal with skill and zeal, their judgment should not be averted from the goal of preserving or improving neurologic function. Consequently, surgeons may be forced at times to accept subtotal removal. However, the concept of decompressive removal to lessen surgical complications followed by fractionated radiation therapy has proven ineffective. For long-term control, clinical recurrence rates after 15 years of subtotal resection and radiation therapy have reached 75% with a complication rate of 56%.23 The advent of radiosurgery has revived this concept, with authors resorting to subtotal removal followed by adjuvant radiosurgery.24–26 All of these series report a relatively short follow-up that is insufficient to determine the real late recurrence rate, and reports exist on delayed failure of radiosurgery and its aggressive recurrence pattern.27 The concern is the lost opportunity of curative removal at the initial presentation and the risks and difficulties in managing these recurrences.28,29

DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION

Petroclival meningiomas are thought to arise from the region of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis.2,9,30 Over the years there has been ongoing debate as to what the anatomic term “petroclival” includes. Cushing and Eisenhardt included five tumors in their gasseropetrosal group.2 Recognizing that these lesions were unique in their involvement of both the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments simultaneously, they aptly wrote, “… in these cases the fully grown tumors sits like a saddle astride the anterior end of the petrous ridge which demarcates the middle cranial fossa, where the growth organizes from the cerebellar of posterior fossa, where it does its chief damage.”2

Since Cushing and Eisenhardt’s description of the gasseropetrosal meningioma, multiple classification systems have been introduced in the literature. Unfortunately these early classifications were somewhat arbitrary and at best confusing and inconsistent.1–4,9,10,31–35 Castellano and Ruggiero, reviewing autopsy data, described meningiomas of the posterior fossa based on the site of their dural attachment.3 They divided the tumors into five groups: cerebellar convexity, tentorium, posterior surface of the petrous bone, clivus, and foramen magnum. In an appendix to the group, they added those “meningiomas of the cavum Meckelii extending into the posterior fossa.” Although Castelanno and Ruggiero believed these should be middle fossa tumors, they conceded that they should be classified as clival tumors for anatomic, pathologic, and radiologic reasons.3

Yaşargil and colleagues differentiated the posterior fossa meninigiomas based on intraoperative observations.1 The absence of a purely medial clival origin, as well as the absence of associated hyperostosis along the middle region, impressed them. They described these meningiomas as “attached at any of the lateral sites along the petroclival borderline where the sphenoid, petrous, and occipital bones meet.” Based on their findings, they classified the posterior fossa locations as clival, petroclival, sphenopetroclival, foramen magnum, and cerebellopontine angle.1 Therefore, based on surgical anatomy, natural history, and results, most authors use the term “petroclival” to describe meningiomas located along the superior two thirds of the clivus and medial to the Vth cranial nerve arising from the spheno-occipital synchondrosis.1,2,5,9,30,36,37 Meningiomas arising from the lower one third of the clivus are typically classified as foramen magnum and are not addressed in this chapter.

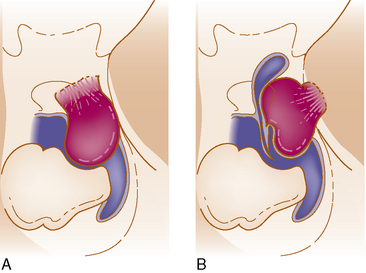

We believe the site of origin must be the basis of classification because of its effect on the pathologic anatomy and the subsequent displacement of the neurovascular structure with a profound influence on the surgical intervention and its outcome.20 The presence of multiarachnoid layers that facilitate safe neurovascular dissection is influenced by a few millimeters difference in the origin (Fig. 36-1).

This principle was recently stressed and presented also by others with a report of their classification.38

Table 36-1 shows the classification relating the tumor origin with the corresponding pathologic anatomy, tumor invasion, and the influence selection of the surgical approach (Fig. 36-2).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The typical presentation of a petroclival meningioma is that of an insidious onset. Most studies report that the period of symptoms before diagnosis averages between 2.5 and 5 years, ranging from 1 month to 17 years.1,4,5,8–10,19,39 The tumor’s inconsistent and variable presentation testifies to this diagnostic dilemma, especially before the introduction of modern neuroradiologic techniques. The clinical presentations can be divided into four groups based on involvement of the cranial nerves, mass effect on the cerebellum, brain stem compression and increased intracranial pressure, and whether the source of the symptoms is the tumor mass or obstructive hydrocephalus.9,10

Cranial neuropathies are commonly associated with petroclival meningiomas. The Vth and VIIIth cranial nerves are the most frequently involved, up to 70% in some series. Facial nerve involvement occurs in about half of the patients.1,5,10,16,19,36 The lower cranial nerves are involved in about one third of cases, usually associated with the larger tumors extending inferiorly.5,10 Interestingly, despite their proximity and in many cases intimate involvement, cranial nerves III, IV, and VI are involved in fewer than half of the cases.1,5,10 In the series reported by Hakuba and colleagues, the incidence of abducens neuropathy was 40% and oculomotor paresis was present in 27%.10 The true incidence of trochlear nerve involvement in these patients is not well documented owing to the lack of preoperative formal examinations.

Cerebellar signs are the most frequently identified clinical findings in these patients.1,5,8,10,18,36,39 Hakuba and colleagues reported ataxia in 70% of their patients.10 Mayberg and Symon’s series supported this finding.36 Headaches are present in about 70% of patients. Long tract signs and somatosensory deficits, consistent with brain stem compression, are variable. Spastic paresis has been reported in 15% to 57% of patients and somatosensory deficits are identified in 15% to 20%.1,5,8,10,18,36,39,40 Despite occasional reports of false localizing signs in meningiomas of the posterior fossa, most series report findings appropriate to the tumor’s location.1,3,10,36,41–43 A clival meningioma seldom produces a syndrome of basilar insufficiency.4

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Clinical Examination

A comprehensive preoperative evaluation is critical in choosing the treatment modality and the surgical approach. Complete clinical, neurologic, audiologic, endocrinologic, and ophthalmologic examinations are performed. The audiogram results will not only provide the clinician with a useful baseline of the patient’s cranial nerve VIII function, it will also give insight into the limitations of the surgical approach. As in acoustic schwannoma patients who elect to postpone surgery, serial examinations of these patients with regard to hearing preservation may provide the impetus for resection of the tumor. As stated earlier, hearing loss can be clinically present in up to three quarters of these patients.1,5,10,19,36 In addition, neuron-ophthalmologic examination preoperatively detects cranial neuropathies involving CN III, IV, and/or VI.1,5,10 As expected, sphenopetroclival meningiomas and petroclival meningiomas extending into the cavernous sinus have a higher rate of extraocular motor neuropathies. In cases of suprasellar tumor extension in patients with sphenopetroclival meningiomas, formal visual field testing preoperatively will reveal the corresponding defect.

Additional testing is dictated by the size and extension of the tumor. In patients with a large supratentorial extension, especially into the suprasellar space, pituitary axis evaluation may be necessary. Patients with evidence of hypothyroidism or hypocortisol levels should be treated preoperatively. Patients with significant tumor extension into the area of the medulla are at risk for lower cranial difficulties. Preoperative deficits involving the lower cranial nerves (IX, X, and XI) occur in up to one third of patients and warrants formal evaluation with endoscopic visualization of the vocal cords and video swallowing test.5,10

Radiographic Examination

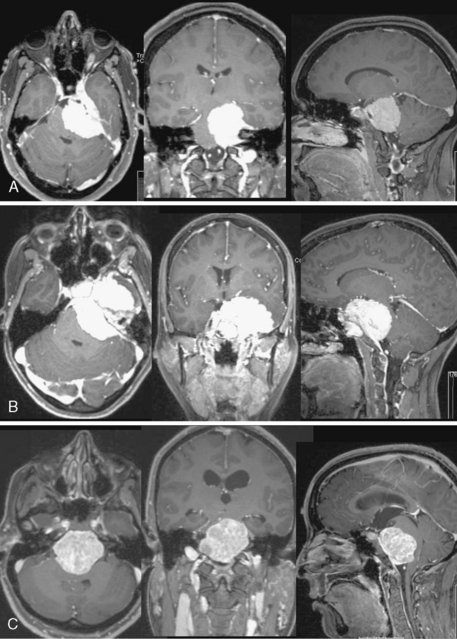

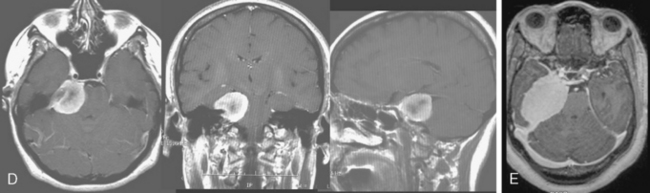

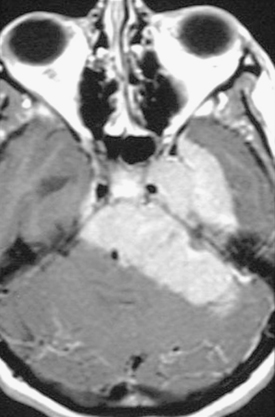

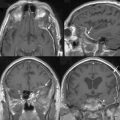

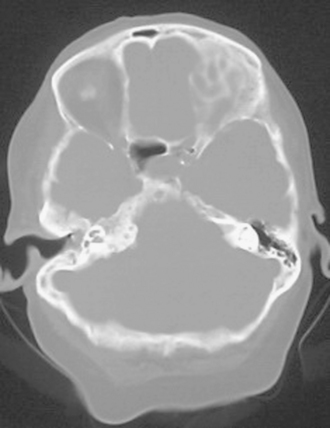

The preoperative evaluation should include a detailed radiographic examination of the tumor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes is essential to understanding the anatomy of the tumors; it characteristics; its pattern or extension, especially into the cavernous sinus; its involvement of the vascular structures; its relation to the brain stem; and the presence and extent of associated peritumoral edema and hydrocephalus (Fig. 36-3). Computed tomography (CT) is particularly useful for the examination of the tumors and its relation to the temporal bone. Hyperostosis, a hallmark of tumor invasion of the bone in skull-base meningiomas, has been reported in up to 17% of cases.39,44–48 A review of our patient series of petroclival and sphenopetroclival tumors showed a high incidence of radiographic evidence of hyperostosis indicating bony invasion (Fig. 36-4). A T2 hyperintensity signal in the brain stem was reported to indicate pia invasion and associated with high complication.49 T2 hyperintensity of the tumor itself is usually indicative of soft tumor that can be drawn up that is associated with ease of dissection and resection. MRI and CT studies are performed on a neuronavigation protocol, to aid intraoperative surgical planning and resection. Images of the cerebral vasculature including the carotid, vertebral, and venous systems is indispensable in the preoperative planning process. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA and MRV) has largely replaced conventional angiography. Examination of the basilar artery typically shows displacement of the artery dorsally and laterally, away from the tumor side. However, if the tumor arises primarily ventral to the basilar trunk, along the clivus, displacement may only be dorsally and lateral displacement of the artery may be absent. Absence of any displacement in these tumors does not rule out basilar trunk involvement. Occasionally the basilar artery is centered in the tumor, in which case no displacement may be appreciated. In addition, narrowing of the artery in the area of tumor involvement should alert the surgeon to the possibility of vascular encasement. Typically, the posterior and superior cerebellar arteries are displaced superiorly, more so on the side of the tumor. In cases where the tumor extends though the tentorial hiatus, the two arteries may be splayed apart.

FIGURE 36-4 CT scan bony window demonstrating hyperostosis of right petrous apex that indicates bony invasion.

Carotid angiography is helpful in demonstrating the dural arterial supply to the tumor. Vascular supply arising from the internal carotid artery at the siphon is well documented in these tumors.10,50,51 In addition, the external carotid artery may provide additional supply to the tumor via the ascending pharyngeal and middle meningeal arteries. In cases of cavernous sinus extension or in sphenopetroclival tumors, examination of the internal carotid artery is equally important. Again, as in the case of the basilar trunk, displacement of the artery and/or the presence of focal narrowing should increase the surgeon’s suspicion of carotid artery wall involvement. Extensive involvement may lead to carotid occlusion of the risk of it; hence, angiography become necessary in these cases to delineate collateral circulation.

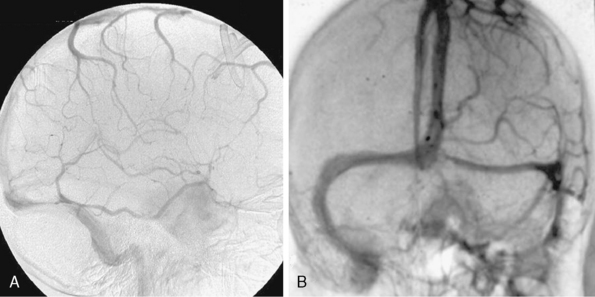

Of paramount importance is the study of the venous system anatomy. Evaluating the patency of the connection, or lack thereof, of the two transverse sinuses is especially important in the presurgical planning. Occasionally, the deep and superficial venous system of the brain can be drained separately, each by a separate transverse sinus. Typically there is a dominant transverse sinus; however, this becomes significant when one of the sinuses is extremely hypoplastic or atretic. Finally, examination of the location and anatomy of the cortical draining veins should be emphasized, particularly the course and position of the vein of Labbé (Fig. 36-5). Many of the surgical exposures used in accessing the petroclival region will require dissection in the vicinity of this vein, and the importance of avoiding injury to this structure cannot be overemphasized.

MANAGEMENT

Petroclival meningiomas remain the most challenging in their management and the most worrisome in their treatment. At present, there is a resurgence of controversy about the management paradigm. The natural history has been described in the past as universally progressive and fatal.2,3,9 This relentless growth and deterioration is reconfirmed with a contemporary study reported by Van Havenbergh and colleagues of 21 patients who were followed conservatively for a minimum of 4 years. Seventy-six percent of the lesions demonstrated growth; 63% had neurologic deterioration, and change in the growth pattern often proceeded functional deterioration.52 Likewise, studies showed a variable rate of growth of residual tumor after surgery, with overall growth rate of residual petroclival meningiomas of 0.37 cm/year in diameter and 4.94 mL/year in volume with old age and occurrence of menopause associated with slower growth.24

A total surgical removal that achieves grade 1 or 2 Simpson resection offers a cure and associated on long-term follow-up with minimal recurrence rate.53 It is the optimal goal in treating petroclival meningiomas. The gravity of this undertaking was expressed by Cushing and Eisenhardt when they warned that any operation aimed at surgical extirpation of tumors, which straddled the petrous ridge, was fruitless. They stated that the removal of such tumors in the future would mark another conquest for the field of neurosurgery.1 The early literature, the series before 1980, reported an operative mortality exceeding 50%.3,4,10,34 In fact, before 1970 only one case of a successful gross total removal had been reported.4 The advent of microsurgery and skull-base surgery, which provided the necessary technique and approaches to remove these tumors safely, has provided a remarkable achievement in the surgical ability and safety of removing these tumors (Table 36-2).1,5,8,15–17,24,25,38–40,49,54–66 In most cases the limitation of achieving total surgical removal was from extensive involvement of the cavernous sinus. The presence of cranial nerve deficit before surgery is predictive of worsening postoperative cranial nerve functioning.15 These series also confirm that recurrences are associated with subtotal removal. However, the demanding surgical undertaking, the burden of caring for potential complications, and the associated risks of cranial nerve deficits that purportedly negatively influence the quality of life have lately led some authors to adapt a philosophy of subtotal resection.24,25,40,61,66–68 The past decade has seen an increase in radiosurgical treatment of petroclival meningiomas, both as initial therapy and as an adjuvant to surgical resection.69–73 However, this option is reserved for treatment of relatively small tumors. Conformal fractionated radiation therapy may be used to treat tumors of all sizes and sites.74,75 Radiosurgery and conformal radiation are also associated with significant radiation-induced complications and concern of malignances and may not reduce the mass effect of larger tumors.27,76–85

We recommend surgical resection in cases of younger patients with larger or growing tumors. Cases of subtotal surgical resection of a meningioma can be followed for evidence of progression before treatment with radiosurgery or conformal radiation therapy. Patients with high-grade meningiomas, as determined by pathologic analysis after resection, may benefit from adjuvant radiation therapy. The discussion of radiosurgery in the treatment of meningiomas is beyond the scope of this writing, but it is important to mention delayed failures are not only occurring but are associated with an aggressive growth pattern of these meningiomas.27 The common experience of surgeons operating on patients previously treated with radiosurgery is that of difficulties with lesser chance of achievement of total removal and increased risks, despite the numerous published articles on the effectiveness of radiosurgery on petroclival meningiomas, primary or residual.24,72 Recent articles that report on long-term survival of meningioma patients who were treated with radiosurgery shows a 15-year actuarial survival of 53%, with 67% dying of their meningioma.86

[1] Yasargil M.G., Mortara R.W., Curcic M. Meningiomas of basal posterior cranial fossa. In: Krayenbul-d H., editor. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1980:3-118.

[2] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas of the cerebellar chamber. In: Cushing H., Eisenhardt L., editors. Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behavior. Life History and Surgical End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1938:169-223.

[3] Castellano F., Ruggiero G. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Acta Radiol. 1953;104(Suppl):1-157.

[4] Campbell E., Whitfield R.D. Posterior fossa meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1949;5:131-153.

[5] Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L., Smith R.R. Petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:510-517.

[6] Drake J.M., Hoffman H.J. Meningiomas in childhood. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:145-152.

[7] Germano I.M., Edwards M.S.B., Davis R.L., Schiffer D. Intracranial meningiomas of the first two decades of life. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:447-453.

[8] Bricolo A.P., Turazzi S., Talacchi A., Cristofori L. Microsurgical removal of petroclival meningiomas: a report of 33 patients. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:813-828.

[9] Cherington M., Schneck S.A. Clivus meningiomas. Neurology. 1966;16:86-92.

[10] Hakuba A., Nishimura S., Tanaka K., et al. Clivus meningiomas: six cases of total removal. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1977;17:63-77.

[11] Olivecrona H. The surgical treatment of intracranial tumors. In: Olivecrona H., Tönnis W., editors. Handbuch der Neurochirurgie. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1967:1-301.

[12] Hakuba A., Nishimura S., Jang B.J. A combined retroauricular and preauricular transpetrosal approach to clivus meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 1988;30:108-116.

[13] Sekhar L.N., Samii M. Petroclival and medial tentorial meningiomas. In: Scheunemann H., Schürmann K., Helms J., editors. Tumors of the Skull Base: Extra- and Intracranial Surgery of Skull Base Tumors. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 1986:141-158.

[14] Sekhar L.N., Jannetta P.J. Petroclival and medial tentorial meningiomas. In: Sekhar L.N., Schramm V.L.Jr, editors. Tumors of the Cranial Base: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mount Kisco, NY: Futura; 1987:623-640.

[15] Natarajan S.K., Sekhar L.N., Schessel D., Morita A. Petroclival meningiomas: multimodality treatment and outcomes at long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:965-979.

[16] Little K.M., Friedman A.H., Sampson J.H., et al. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: defining resection goals based on risk of neurological morbidity and tumor recurrence rates in 137 patients. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:546-559.

[17] Kawase T., Shiobara R., Toya S. Middle fossa transpetrosal-transtentorial approaches for petroclival meningiomas. Selective pyramid resection and radicality. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;129:113-120.

[18] Sekhar L.N., Jannetta P.J., Burkhart L.E., Janosky J.E. Meningiomas involving the clivus: A six-year experience with 41 patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:764-781.

[19] Symon L. Surgical approaches to the tentorial hiatus. Krayenbuhl H., editor. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery, vol. 9. Springer-Verlag, Vienna, 1982;69-112.

[20] Al-Mefty O. Operative Atlas of Meningiomas. New York: Lippincott-Raven Press, 1997.

[21] Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1957;20:22-39.

[22] Mirimanoff R.E., Dosoretz D.E., Linggood R.M., et al. Meningioma: Analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:18-24.

[23] Mathiesen T., Kihlström L., Karlsson B., Lindquist C. Potential complications following radiotherapy for meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:193-200.

[24] Jung H.W., Yoo H., Paek S.H., Choi K.S. Long-term outcome and growth rate of subtotally resected petroclival meningiomas: Experience with 38 cases. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:567-574.

[25] Bambakidis N.C., Kakarla U.K., Kim L.J., et al. Evolution of surgical approaches in the treatment of petroclival meningiomas: a retrospective review. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(6 Suppl 3):1182-1191.

[26] Pamir M.N., Kilic T., Bayrakli F., Peker S. Changing treatment strategy of cavernous sinus meningiomas: experience of a single institution. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(Suppl 2):58-66.

[27] Couldwell W.T., Cole C.D., Al-Mefty O. Patterns of skull base recurrence after failed radiosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:30-35.

[28] Ware M.L., Al-Mefty O. Comment on Bambakidis et al: Evolution of surgical approaches in the treatment of petroclival meningiomas: a retrospective review. Oper Neurosurg. 2007;61(5):ONS211.

[29] Borba L.A., Oliveira E.P. Comment on Bambakidis et al: Evolution of surgical approaches in the treatment of petroclival meningiomas: a retrospective review. Oper Neurosurg. 2007;61(5):ONS210.

[30] McKern T.W., Stewart T.D. Skeletal changes in young American males. Natrick, MA: Quarter Master Research and Development Center, 1957.

[31] Rasdolsky I. Zur frage der klinik der meningiome der hinteren schädelgrube. Z ges Neurol Psychiat. 1936;156:211-244.

[32] Morello G., Paleari A. I meningiomas della fossa cranica posteriore. Chirurgie. 1949;4:239.

[33] Petit-Dutaillis P., Daum S. Les méningiomes de la fosse postérieure. Rev Neurol. 1949;81:557-572.

[34] Dany A., Delcour J., Laine E. Les méningiomes du clivus. Neurochirurgie. 1963;9:249-277.

[35] Lecuire J., Dechaume J.P., Buffard P., Bochu M. Les méningiomes de la fosse cérébrale postérieure. Neurochirurgie (Suppl). 1971;17:1-146.

[36] Mayberg M.R., Symon L. Meningiomas of the clivus and apical petrous bone: report of 35 cases. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:160-167.

[37] Couldwell W.T., Weiss M.G. Surgical approaches to petroclival meningioma. Part I: Upper and midclival approaches. Contemp Neurosurg. 1994;16:1-6.

[38] Ichimura S., Kawase T., Onozuka S., et al. Four subtypes of petroclival menigiomas: differences in symptoms and operative findings using the anterior transpetrosal approach. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150:637-645.

[39] Samii M., Ammirati M., Mahran A., et al. Surgery of petroclival meningiomas: report of 24 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:12-17.

[40] Zentner J., Meyer B., Vieweg U., et al. Petroclival meningiomas: is radical resection always the best option. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:341-345.

[41] Hamby W.B. Trigeminal neuralgia due to contralateral tumors of the posterior cranial fossa. Report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg. 1947;4:179-182.

[42] Nagahiro S., Matsukado Y., Uemura S. Posterior fossa meningioma with special reference to false localizing sign. Neurol Med Chir. 1982;22:421-428.

[43] Petit-Dutaillis P., Daum S., Houdart P., Faurel J. L’atteinte controlatéral dur trijumeau dans les tumeurs de l’angle ponto-cérébelleux. Rev Neurol. 1949;81:139-145.

[44] Poilici I., Mester E., Marinchesco C. Le méningiome du clivus, facteur etiologique du syndrome d’insuffisance circulatoire du tronc de l’artére basilaire. Rev Neurol. 1959;101:722-730.

[45] Pieper D.R., Al-Mefty O., Hanada Y., Buechner D. Hyperostosis associated with meningioma of the cranial base: secondary changes or tumor invasion. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:742-747.

[46] Derome P.J., Guiot G. Bone problems in meningiomas invading the base of the skull. Clin Neurosurg. 1978;25:435-451.

[47] Echlin F. Cranial osteomas and hyperostoses produced by meningeal fibroblastomas. Arch Surg. 1934;28:3357-3405.

[48] Globus J.H. The meningiomas. Trans Assn Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1937;16:210.

[49] Sekhar L.N., Wright D.C., Richardson R., Monacci W. Petroclival and foramen magnum meningiomas: Surgical approaches and pitfalls. J Neurooncol. 1996;29:249-259.

[50] Salamon G.M., Combalbert A., Raybaud C., Gonzalez J. An angiographic study of meningiomas of the posterior fossa. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:731-741.

[51] Al-Mefty O. Surgery of the Cranial Base. Boston: Kluwer Academic, 1989.

[52] Van Havenbergh T., Carvalho G., Tatagiba M., et al. Natural history of petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:55-62.

[53] Mathieson T., Lindquist C., Kihlstrom L., Karlsson B. Recurrence of cranial base meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1996;29:2-9.

[54] Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press, 1991.

[55] Ramina R., Neto M.C., Fernandes Y.B., et al. Surgical removal of small petroclival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150:431-438.

[56] Couldwell W.T., Fukushima T., Giannotta S.L., Weiss M.H. Petroclival meningiomas: surgical experience in 109 cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:20-28.

[57] Hakuba A., Nishimura S. Total removal of clivus meningiomas and the operative results. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1981;21:59-73.

[58] Nishimura S., Hakuba A., Jang B.J., Inoue Y. Clivus and apicopetroclivus meningiomas: report of 24 cases. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1989;29:1004-1011.

[59] Samii M., Tatagiba M. Experience with 36 surgical cases of petroclival meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;118:27-32.

[60] Spetzler R.F., Daspit C.P., Pappas C.T. The combined supra- and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:588-599.

[61] Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6:27-30.

[62] Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa: surgical technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:235-241.

[63] Roberti F., Sekhar L.N., Kalavakonda C., Wright D.C. Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:8-20.

[64] Seifert V., Raabe A., Zimmermann M. Conservative (labyrinth-preserving) transpetrosal approach to the clivus and petroclival region: indications, complications, results and lessons learned 76. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:631-642.

[65] Goel A., Muzumdar D. Conventional posterior fossa approach for surgery on petroclival meningiomas: a report on an experience with 28 cases. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:332-338.

[66] Park C.K., Jung H.W., Kim J.E., et al. The selection of the optimal therapeutic strategy for petroclival meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:160-165.

[67] Mathieson T., Gerlich A., Kihlstrom L., et al. Effects of using combined transpetrosal surgical approaches to treatment petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(6):982-991.

[68] Abdel Aziz K.M., Sanan A., van Loveren H.R., et al. Petroclival meningiomas: Predictive parameters for transpetrosal approaches. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(1):139-152.

[69] Iwai Y., Yamanaka K., Yasui T., et al. Gamma knife surgery for skull base meningiomas. The effectiveness of low-dose treatment. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:40-44.

[70] Roche P.H., Pellet W., Fuentes S., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgical management of petroclival meningiomas results and indications. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:883-888.

[71] Stafford S.L., Pollock B.E., Foote R.L., et al. Meningioma radiosurgery: tumor control, outcomes, and complications among 190 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1029-1037.

[72] Subach B.R., Lunsford L.D., Kondziolka D., et al. Management of petroclival meningiomas by stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(3):437-445.

[73] Zachenhofer I., Wolfsberger S., Aichholzer M., et al. Gamma-knife radiosurgery for cranial base meningiomas: experience of tumor control, clinical course, and morbidity in a follow-up of more than 8 years. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:28-36.

[74] Goldsmith B., McDermott M.W. Meningioma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2006;17:111-129. vi

[75] Noel G., Bollet M.A., Calugaru V., et al. Functional outcome of patients with benign meningioma treated by 3D conformal irradiation with a combination of photons and protons. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1412-1422.

[76] Kaido T., Hoshida T., Uranishi R., et al. Radiosurgery-induced brain tumor. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:710-713.

[77] Kleinschmidt-Demasters B.K., Kang J.S., Lillehei K.O. The burden of radiation-induced central nervous system tumors: a single institution’s experience. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:204-216.

[78] Kranzinger M., Jones N., Rittinger O., et al. Malignant glioma as a secondary malignant neoplasm after radiation therapy for craniopharyngioma: report of a case and review of reported case. Onkologie. 2001;24:66-72.

[79] Salvati M., Frati A., Russon N., et al. Radiation-induced gliomas: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:60-67.

[80] Shamisa A., Bance M., Nag S., et al. Glioblastoma multiforme occurring in a patient treatment with gamma knife surgery. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:816-821.

[81] Sheehan J., Yen C.P., Steiner L. Gamma knife surgery-induced meningioma. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:3225-3329.

[82] Shin M., Ueki K., Kurita H., Kirion T. Malignant transformation of a vestibular schwannoma after gamma knife radiosurgery. Lancet. 2002;360:309-310.

[83] Yu J.S., Yong W.H., Wilson D., Black K.L. Glioblastoma induction after radiosurgery for meningioma. Lancet. 2000;356:1576-1577.

[84] Liscak R., Kollova A., Vladyka V., et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery of skull base meningiomas. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2004;91:65-74.

[85] Milker-Zabel S., Zabel-du Bois A., Huber P., et al. Fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy in the management of benign cavernous sinus meningiomas: long-term experience and review of the literature. Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182:635-640.

[86] Rowe J., Grainger A., Walton L., et al. Risk of malignancy after Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:60-66.