Overview of Fungal Identification Methods and Strategies

1. Define the terms mycology, saprophytic, dermatophyte, and polymorphic, dimorphic, and thermally dimorphic fungi.

2. Define and differentiate superficial, cutaneous, subcutaneous, and systemic mycoses, including the tissues involved.

3. Differentiate the colonial morphology of yeasts and filamentous fungi (molds).

4. Define and differentiate anamorph, teleomorph, and synanamorph.

5. Describe three ways in which fungi reproduce.

6. List the media that should be used for optimal recovery of fungi, including their incubation requirements.

7. List the common antibacterial agents used in fungal media.

8. Explain and differentiate the characteristic colonial morphology of fungi, including topography (rugose, umbonate, verrucose), texture (cottony, velvety, glabrous, granular, wooly) and surface described (front, reverse).

9. Describe and differentiate the sexual and asexual reproduction of the Ascomycota.

10. Define and differentiate rapid, intermediate, and slow growth rates with regard to fungal reproduction and cultivation.

11. Describe the proper method of specimen collection for fungal cultures, including collection site, acceptability, processing, transport, and storage.

12. Give the advantages and disadvantages of using screw-capped culture tubes, compared with agar plates, in the laboratory.

13. Describe the chemical principle and methodologies used to identify fungi, including calcofluor white–potassium hydroxide preparations, hair perforation, cellophane (Scotch) tape preparations, saline/wet mounts, lactophenol cotton blue, potassium hydroxide, Gram stain, India ink, modified acid-fast stain, periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS), Wright’s stain, Papanicolaou stain, Grocott’s methenamine silver (GMS), hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, Masson-Fontana stain, tease mount and microslide culture.

General Features of the Fungi

Fungi seen in the clinical laboratory generally can be categorized into two groups based on the appearance of the colonies formed. The yeasts produce moist, creamy, opaque or pasty colonies on media, whereas the filamentous fungi or molds (see Chapters 60 and 61) produce fluffy, cottony, woolly, or powdery colonies. Several systemic fungal pathogens exhibit either a yeast (or yeastlike) phase, and filamentous forms are referred to as dimorphic. When dimorphism is temperature dependent, the fungi are designated as thermally dimorphic. In general, these fungi produce a mold form at 25° to 30°C and a yeast form at 35° to 37°C under certain circumstances.

The medically important dimorphic fungi are Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, C. immitis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Sporothrix schenckii, and Penicillium marneffei (see Chapter 60). C. immitis is not thermally dimorphic. Additionally, some of the medically important yeasts, particularly the Candida species, may produce yeasts forms, pseudohyphae, and/or true hyphae (see Chapter 62). Fungi that have more than one independent form or spore stage in their life cycle are called polymorphic fungi. The polymorphic features of this group of organisms are not temperature dependent.

Taxonomy of the Fungi

• Ergosterol in the cell membrane

• Reproduction by means of spores, produced asexually or sexually

• Lack of susceptibility to antibacterial antibiotics

• Saprophytic nature (derive nutrition from organic materials)

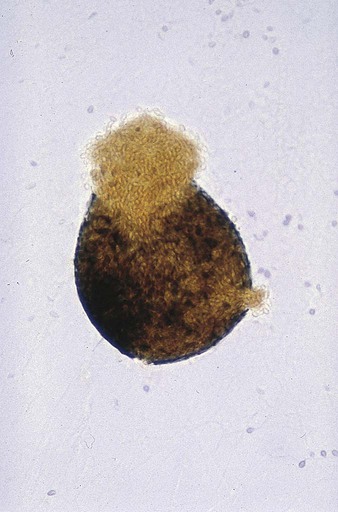

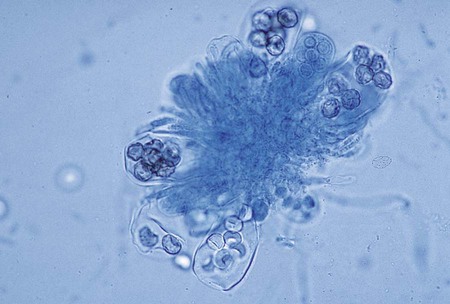

The Ascomycota include many fungi that reproduce asexually by the formation of conidia (asexual spores) and sexually by the production of ascospores. The filamentous ascomycetes are ubiquitous in nature, and all produce true septate hyphae. All exhibit a sexual form (teleomorph) but also exist in an asexual form (anamorph). Fungi that have different asexual forms of the same fungus are called synanomorphs. In general, the anamorphic form correlates well with the teleomorphic classification. However, different anamorphic forms may have the same teleomorphic form. For example, Pseudallescheria boydii (Figure 59-1), in addition to having the Scedosporium apiospermum anamorph (Figure 59-2), may exhibit a Graphium anamorph (Figure 59-3). The latter anamorph may be seen with several other fungi.

Clinical Classification of the Fungi

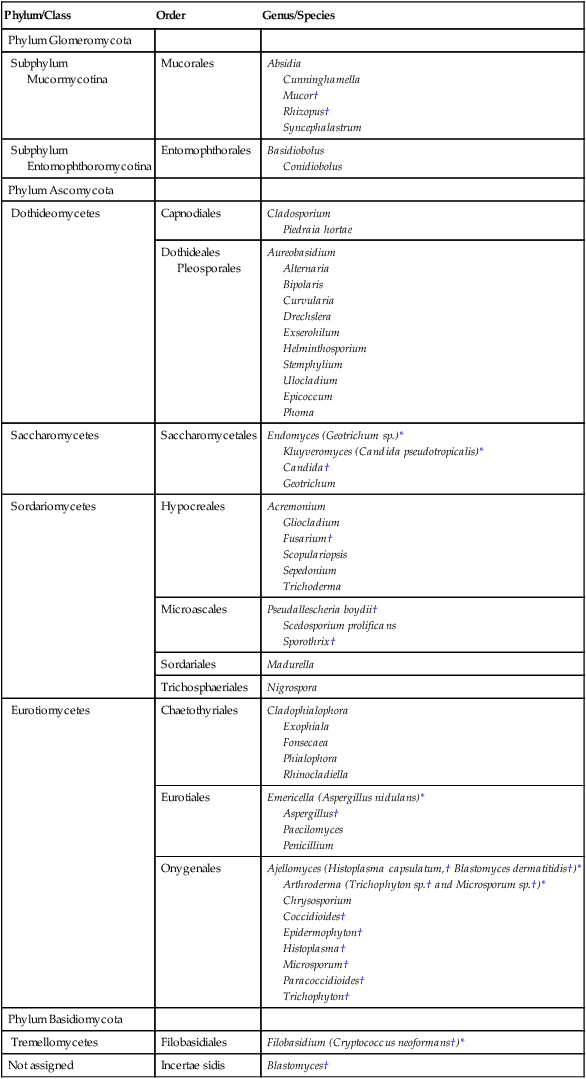

The botanic taxonomic schema for grouping the fungi has little value in a clinical microbiology laboratory. Table 59-1 is a simplified taxonomic schema illustrating the major groups of fungi.

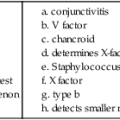

TABLE 59-1

Phylogenetic Position of Medically Significant Fungi

| Phylum/Class | Order | Genus/Species |

| Phylum Glomeromycota | ||

| Subphylum Mucormycotina |

Mucorales | Absidia Cunninghamella Mucor† Rhizopus† Syncephalastrum |

| Subphylum Entomophthoromycotina |

Entomophthorales | Basidiobolus Conidiobolus |

| Phylum Ascomycota | ||

| Dothideomycetes | Capnodiales | Cladosporium Piedraia hortae |

| Dothideales Pleosporales |

Aureobasidium Alternaria Bipolaris Curvularia Drechslera Exserohilum Helminthosporium Stemphylium Ulocladium Epicoccum Phoma |

|

| Saccharomycetes | Saccharomycetales | Endomyces (Geotrichum sp.)* Kluyveromyces (Candida pseudotropicalis)* Candida† Geotrichum |

| Sordariomycetes | Hypocreales | Acremonium Gliocladium Fusarium† Scopulariopsis Sepedonium Trichoderma |

| Microascales | Pseudallescheria boydii† Scedosporium prolificans Sporothrix† |

|

| Sordariales | Madurella | |

| Trichosphaeriales | Nigrospora | |

| Eurotiomycetes | Chaetothyriales | Cladophialophora Exophiala Fonsecaea Phialophora Rhinocladiella |

| Eurotiales | Emericella (Aspergillus nidulans)* Aspergillus† Paecilomyces Penicillium |

|

| Onygenales | Ajellomyces (Histoplasma capsulatum,† Blastomyces dermatitidis†)* Arthroderma (Trichophyton sp.† and Microsporum sp.†)* Chrysosporium Coccidioides† Epidermophyton† Histoplasma† Microsporum† Paracoccidioides† Trichophyton† |

|

| Phylum Basidiomycota | ||

| Tremellomycetes | Filobasidiales | Filobasidium (Cryptococcus neoformans†)* |

| Not assigned | Incertae sidis | Blastomyces† |

*When the sexual form is known.

†Most commonly encountered as causes of infection.

Modified from the Catalogue of Life. November 20, 2012. http://www.catalogueoflife.org/col/browse/classification and Hibbet DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, et al. A higher-level of classification of the fungi, Mycological Research, 509-547, 2007.

Some fungi cause infections that are confined to the subcutaneous tissue without dissemination to distant sites. Examples of subcutaneous infections include chromoblastomycosis, mycetoma, and phaeohyphomycotic cysts (see Chapter 61).

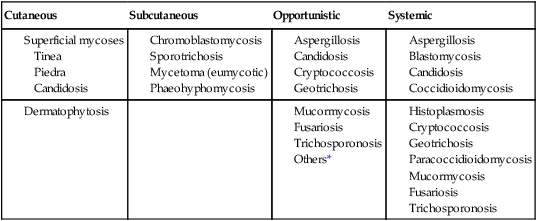

Classification by type of infection allows the clinician to attempt to categorize organisms in a logical fashion into groups having clinical relevance. Table 59-2 presents an example of a clinical classification of infections and their etiologic agents that is useful to clinicians.

TABLE 59-2

General Clinical Classification of Pathogenic Fungi

| Cutaneous | Subcutaneous | Opportunistic | Systemic |

*Virtually any fungus may cause disease in a profoundly immunocompromised host.

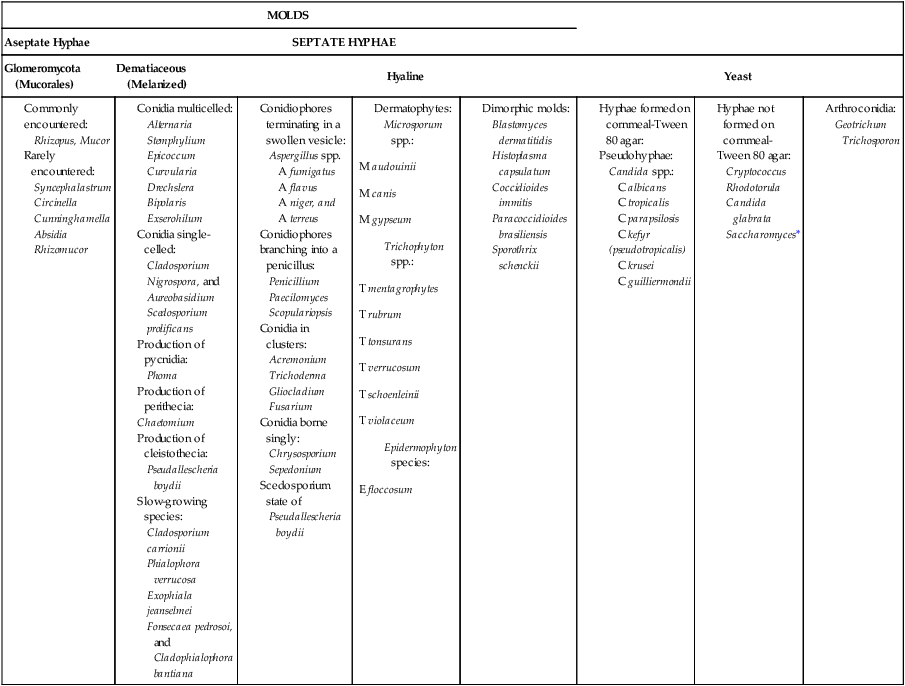

Practical Working Schema

To assist individuals working in clinical microbiology laboratories with the identification of clinically important fungi, Koneman and Roberts1 have suggested a practical working scheme designed to do the following:

• Assist with the recognition of fungi most commonly encountered in clinical specimens

• Assist with the recognition of fungi recovered on culture media that are strictly pathogenic fungi

• Provide a pathway that allows an identification to be made based on a few colonial and microscopic features

Table 59-3 presents these features. However, the table includes only organisms commonly seen in the clinical laboratory. With practice, most laboratorians should be able to recognize these on a day-to-day basis. For other, less commonly encountered fungi, the microbiologist must use a variety of texts that have photomicrographs, which can aid identification.

TABLE 59-3

Most Commonly Encountered Fungi of Clinical Laboratory Importance: a Practical Working Schema

| MOLDS | |||||||

| Aseptate Hyphae | SEPTATE HYPHAE | ||||||

| Glomeromycota (Mucorales) | Dematiaceous (Melanized) | Hyaline | Yeast | ||||

*Rudimentary hyphae may be present.

From Koneman EW, Roberts GD: Practical laboratory mycology, ed 3, Baltimore, 1985, Williams & Wilkins.

Use of the identification scheme just described requires examination of the fungal culture for the presence, absence, and number of septa. If the hyphae appear to be broad and predominantly nonseptate (i.e., cells are not separated by a septum or wall), zygomycetes should be considered. If the hyphae are septate, they must be examined further for the presence or absence of pigmentation. If a dark pigment is present in the hyphae, the organism is considered to be dematiaceous, and the conidia are then examined for their morphologic features and their arrangement on the hyphae. If the hyphae are nonpigmented, they are considered to be hyaline. The fungi are then examined for the type and the arrangement of the conidia produced. The molds are identified by recognition of their characteristic microscopic features (see Table 59-3). Murray2 has developed an expanded morphologic classification of medically important fungi based on general microscopic features and colonial morphology. The color pigmentation of colonies is presented as a useful diagnostic feature (Box 59-1).

Pathogeneis and Spectrum of Disease

• The organism’s size (with inhalation, the organism must be small enough to reach the alveoli)

• The organism’s ability to grow at 37°C at a neutral pH

• Conversion of the dimorphic fungi from the mycelial form into the corresponding yeast or spherule form in the host

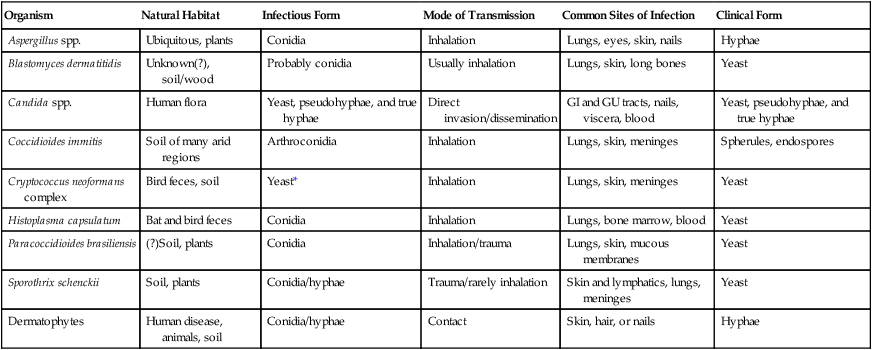

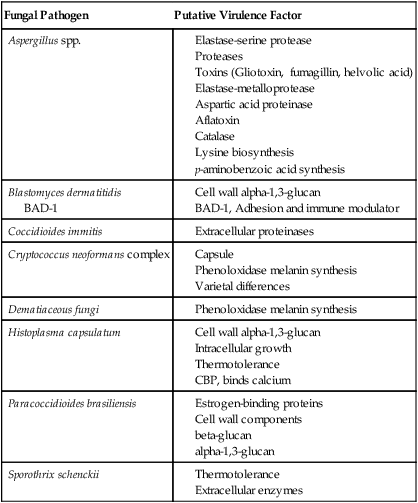

Most of the fungi exist in environmental niches as saprophytic organisms (Table 59-4). Perhaps the fungi that cause disease in humans have developed various mechanisms that allow them to establish disease in the human host. Table 59-5 describes the known or speculative virulence factors of the fungi known to be pathogenic for humans.

TABLE 59-4

| Organism | Natural Habitat | Infectious Form | Mode of Transmission | Common Sites of Infection | Clinical Form |

| Aspergillus spp. | Ubiquitous, plants | Conidia | Inhalation | Lungs, eyes, skin, nails | Hyphae |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | Unknown(?), soil/wood | Probably conidia | Usually inhalation | Lungs, skin, long bones | Yeast |

| Candida spp. | Human flora | Yeast, pseudohyphae, and true hyphae | Direct invasion/dissemination | GI and GU tracts, nails, viscera, blood | Yeast, pseudohyphae, and true hyphae |

| Coccidioides immitis | Soil of many arid regions | Arthroconidia | Inhalation | Lungs, skin, meninges | Spherules, endospores |

| Cryptococcus neoformans complex | Bird feces, soil | Yeast* | Inhalation | Lungs, skin, meninges | Yeast |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Bat and bird feces | Conidia | Inhalation | Lungs, bone marrow, blood | Yeast |

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | (?)Soil, plants | Conidia | Inhalation/trauma | Lungs, skin, mucous membranes | Yeast |

| Sporothrix schenckii | Soil, plants | Conidia/hyphae | Trauma/rarely inhalation | Skin and lymphatics, lungs, meninges | Yeast |

| Dermatophytes | Human disease, animals, soil | Conidia/hyphae | Contact | Skin, hair, or nails | Hyphae |

GI, Gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary.

*Possibly the conidia of the teleomorphic stage (Filobasidiella neoformans).

TABLE 59-5

Virulence Factors of Medically Important Fungi

| Fungal Pathogen | Putative Virulence Factor |

| Aspergillus spp. |

BAD-1

Laboratory Diagnosis

Collection, Transport, and Culturing of Clinical Specimens

Culture Media and Incubation Requirements

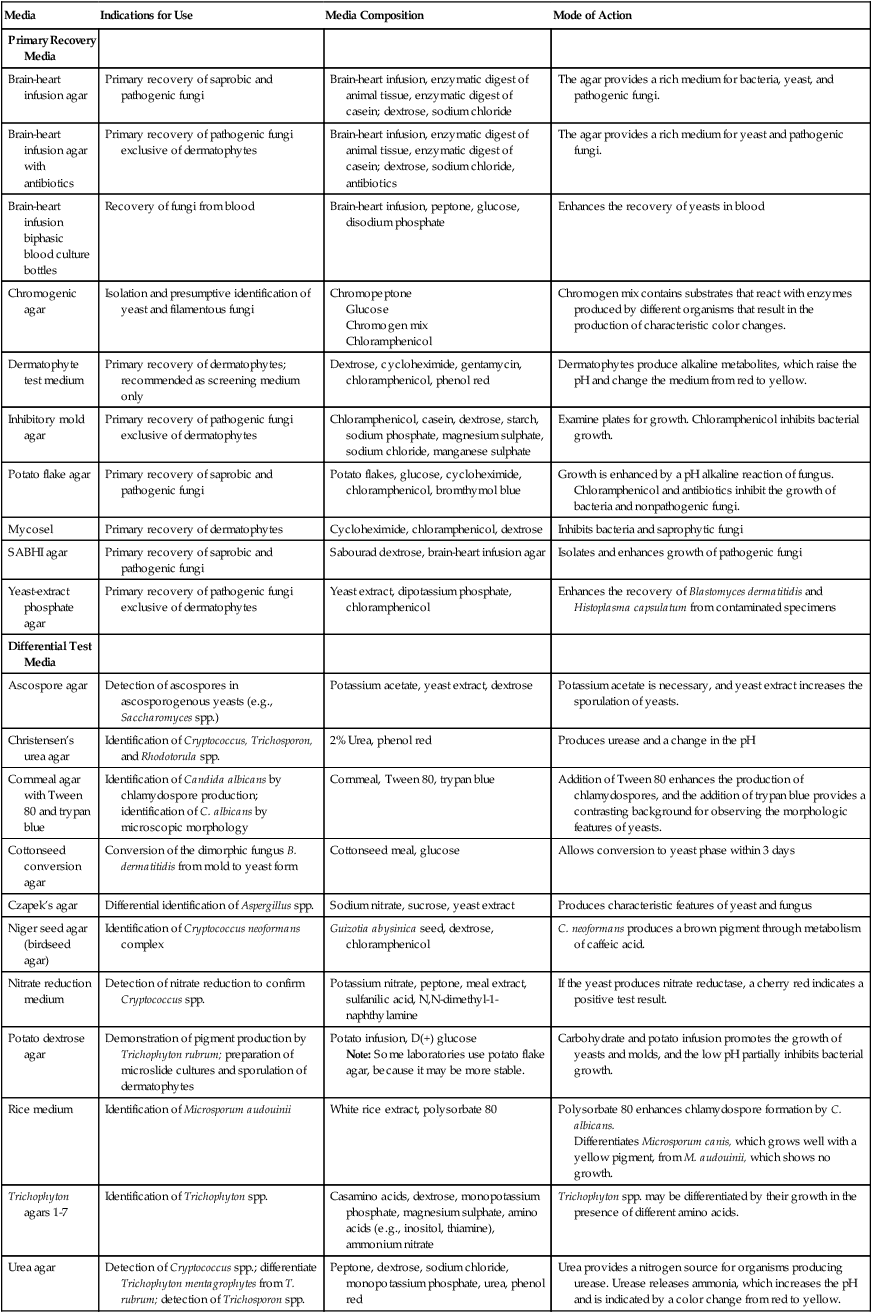

A number of fungal culture media are satisfactory for use in the clinical microbiology laboratory (Table 59-6). Most are adequate for the recovery of fungi, and the selection usually is left up to the laboratory director. For optimal recovery, a battery of media should be used; the following are recommended:

TABLE 59-6

Fungal Culture Media: Indications for Use

| Media | Indications for Use | Media Composition | Mode of Action |

| Primary Recovery Media | |||

| Brain-heart infusion agar | Primary recovery of saprobic and pathogenic fungi | Brain-heart infusion, enzymatic digest of animal tissue, enzymatic digest of casein; dextrose, sodium chloride | The agar provides a rich medium for bacteria, yeast, and pathogenic fungi. |

| Brain-heart infusion agar with antibiotics | Primary recovery of pathogenic fungi exclusive of dermatophytes | Brain-heart infusion, enzymatic digest of animal tissue, enzymatic digest of casein; dextrose, sodium chloride, antibiotics | The agar provides a rich medium for yeast and pathogenic fungi. |

| Brain-heart infusion biphasic blood culture bottles | Recovery of fungi from blood | Brain-heart infusion, peptone, glucose, disodium phosphate | Enhances the recovery of yeasts in blood |

| Chromogenic agar | Isolation and presumptive identification of yeast and filamentous fungi | Chromopeptone Glucose Chromogen mix Chloramphenicol |

Chromogen mix contains substrates that react with enzymes produced by different organisms that result in the production of characteristic color changes. |

| Dermatophyte test medium | Primary recovery of dermatophytes; recommended as screening medium only | Dextrose, cycloheximide, gentamycin, chloramphenicol, phenol red | Dermatophytes produce alkaline metabolites, which raise the pH and change the medium from red to yellow. |

| Inhibitory mold agar | Primary recovery of pathogenic fungi exclusive of dermatophytes | Chloramphenicol, casein, dextrose, starch, sodium phosphate, magnesium sulphate, sodium chloride, manganese sulphate | Examine plates for growth. Chloramphenicol inhibits bacterial growth. |

| Potato flake agar | Primary recovery of saprobic and pathogenic fungi | Potato flakes, glucose, cycloheximide, chloramphenicol, bromthymol blue | Growth is enhanced by a pH alkaline reaction of fungus. Chloramphenicol and antibiotics inhibit the growth of bacteria and nonpathogenic fungi. |

| Mycosel | Primary recovery of dermatophytes | Cycloheximide, chloramphenicol, dextrose | Inhibits bacteria and saprophytic fungi |

| SABHI agar | Primary recovery of saprobic and pathogenic fungi | Sabourad dextrose, brain-heart infusion agar | Isolates and enhances growth of pathogenic fungi |

| Yeast-extract phosphate agar | Primary recovery of pathogenic fungi exclusive of dermatophytes | Yeast extract, dipotassium phosphate, chloramphenicol | Enhances the recovery of Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum from contaminated specimens |

| Differential Test Media | |||

| Ascospore agar | Detection of ascospores in ascosporogenous yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces spp.) | Potassium acetate, yeast extract, dextrose | Potassium acetate is necessary, and yeast extract increases the sporulation of yeasts. |

| Christensen’s urea agar | Identification of Cryptococcus, Trichosporon, and Rhodotorula spp. | 2% Urea, phenol red | Produces urease and a change in the pH |

| Cornmeal agar with Tween 80 and trypan blue | Identification of Candida albicans by chlamydospore production; identification of C. albicans by microscopic morphology | Cornmeal, Tween 80, trypan blue | Addition of Tween 80 enhances the production of chlamydospores, and the addition of trypan blue provides a contrasting background for observing the morphologic features of yeasts. |

| Cottonseed conversion agar | Conversion of the dimorphic fungus B. dermatitidis from mold to yeast form | Cottonseed meal, glucose | Allows conversion to yeast phase within 3 days |

| Czapek’s agar | Differential identification of Aspergillus spp. | Sodium nitrate, sucrose, yeast extract | Produces characteristic features of yeast and fungus |

| Niger seed agar (birdseed agar) | Identification of Cryptococcus neoformans complex | Guizotia abysinica seed, dextrose, chloramphenicol | C. neoformans produces a brown pigment through metabolism of caffeic acid. |

| Nitrate reduction medium | Detection of nitrate reduction to confirm Cryptococcus spp. | Potassium nitrate, peptone, meal extract, sulfanilic acid, N,N-dimethyl-1-naphthylamine | If the yeast produces nitrate reductase, a cherry red indicates a positive test result. |

| Potato dextrose agar | Demonstration of pigment production by Trichophyton rubrum; preparation of microslide cultures and sporulation of dermatophytes | Potato infusion, D(+) glucose Note: Some laboratories use potato flake agar, because it may be more stable. |

Carbohydrate and potato infusion promotes the growth of yeasts and molds, and the low pH partially inhibits bacterial growth. |

| Rice medium | Identification of Microsporum audouinii | White rice extract, polysorbate 80 | Polysorbate 80 enhances chlamydospore formation by C. albicans. Differentiates Microsporum canis, which grows well with a yellow pigment, from M. audouinii, which shows no growth. |

| Trichophyton agars 1-7 | Identification of Trichophyton spp. | Casamino acids, dextrose, monopotassium phosphate, magnesium sulphate, amino acids (e.g., inositol, thiamine), ammonium nitrate | Trichophyton spp. may be differentiated by their growth in the presence of different amino acids. |

| Urea agar | Detection of Cryptococcus spp.; differentiate Trichophyton mentagrophytes from T. rubrum; detection of Trichosporon spp. | Peptone, dextrose, sodium chloride, monopotassium phosphate, urea, phenol red | Urea provides a nitrogen source for organisms producing urease. Urease releases ammonia, which increases the pH and is indicated by a color change from red to yellow. |

| Yeast fermentation broth | Identification of yeasts by determining fermentation | Yeast extract, peptone, bromcresol purple, and a specific carbohydrate (e.g., dextrose, maltose, sucrose) | Most yeasts produce acid, which is indicated by a change in the solution from purple to yellow as a positive fermenter. |

| Yeast nitrogen base agar | Identification of yeasts by determining carbohydrate assimilation | Ammonium sulphate, carbon source (e.g., glucose, sucrose, raffinose) | Assimilation of carbon by yeast cells produces a positive result. |

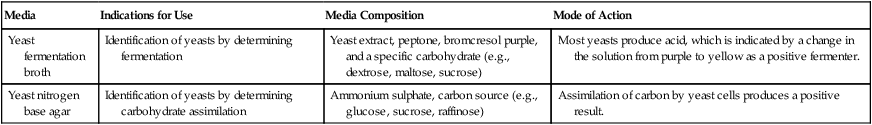

Direct Microscopic Examination

Tables 59-7 and 59-8 present the methods available for direct microscopic detection of fungi in clinical specimens and a summary of the characteristic microscopic features of each. Figure 59-4 presents photomicrographs of some of the fungi commonly seen in clinical specimens.

TABLE 59-7

Summary of Methods Available for Direct Microscopic Detection of Fungi in Clinical Specimens

| Method | Use | Time Required | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Acid-fast stain and partial acid-fast stain | Detection of mycobacteria and Nocardia spp., respectively | 12 min | Detects Nocardia spp.* and some isolates of Blastomyces dermatitidis | Tissue homogenates are difficult to observe because of background staining. |

| Auramine-rhodamine stain | Detection of mycobacteria and Nocardia spp., respectively | 10 min | Excellent screening tool; sensitive and affordable | Not as specific for acid-fast organisms as Ziehl-Neelsen stain |

| Calcofluor white stain | Detection of fungi | 1 min | Can be mixed with KOH: detects fungi rapidly because of bright fluorescence | Requires use of a fluorescence microscope; background fluorescence prominent, but fungi exhibit more intense fluorescence; vaginal secretions are difficult to interpret. |

| Gram stain | Detection of bacteria | 3 min | Commonly performed on most clinical specimens submitted for bacteriology; detects most fungi. | Some fungi stain well, but others (e.g., Cryptococcus spp.) show only stippling and stain weakly in some instances; some isolates of Nocardia spp. fail to stain or stain weakly. |

| India ink stain | Detection of Cryptococcus neoformans in CSF | 1 min | Diagnostic of meningitis when positive in CSF | Positive in fewer than 50% of cases of meningitis; not sensitive in non–HIV-infected patients |

| Lactophenol cotton blue wet mount | Most widely used method of staining and observing fungi | 1 min | Lactic acid preserves structures; slides can be made permanent. | Mechanical treatment dislodges fungal structures. |

| Potassium hydroxide | Clearing of specimen to make fungi more readily visible | 5 min; if clearing is not complete, an additional 5-10 min is necessary | Rapid detection of fungal elements | Requires experience, because background artifacts are often confusing; clearing of some specimens may require an extended time. |

| Masson-Fontana stain | Examination of melanin pigment in fungal cell walls | 1 hr, 10 min | Aids differentiation of melanin and hemosiderin pigments | Difficult to interpret when only rare granular staining is present |

| Methenamine silver stain | Detection of fungi in histologic section | 1 hr | Best stain for detecting fungal elements | Requires a specialized staining method that is not usually readily available to microbiology laboratories |

| Papanicolaou stain | Examination of secretions for malignant cells | 30 min | Cytotechnologist can detect fungal elements. | Fungal elements stain pink to blue. |

| Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain | Detection of fungi | 20 min; 5 min additional if counterstain is used | Stains fungal elements well; hyphae of molds and yeasts can be readily distinguished. | Nocardia spp. do not stain well. |

| Saline wet mount | Examination of fungal elements | 1 min | Quickly performed and cost-effective | Specimen must be fresh; not all elements are visible with this preparation. |

| Wright’s stain | Examination of bone marrow or peripheral blood smears | 7 min | Detects Histoplasma capsulatum and C. neoformans | Most often used to detect H. capsulatum and C. neoformans complex in disseminated disease. |

CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; KOH, potassium hydroxide.

*Partially acid-fast bacterium.

From Versalovic J: Manual of clinical microbiology, ed 10, Washington, DC, 2011, ASM Press.

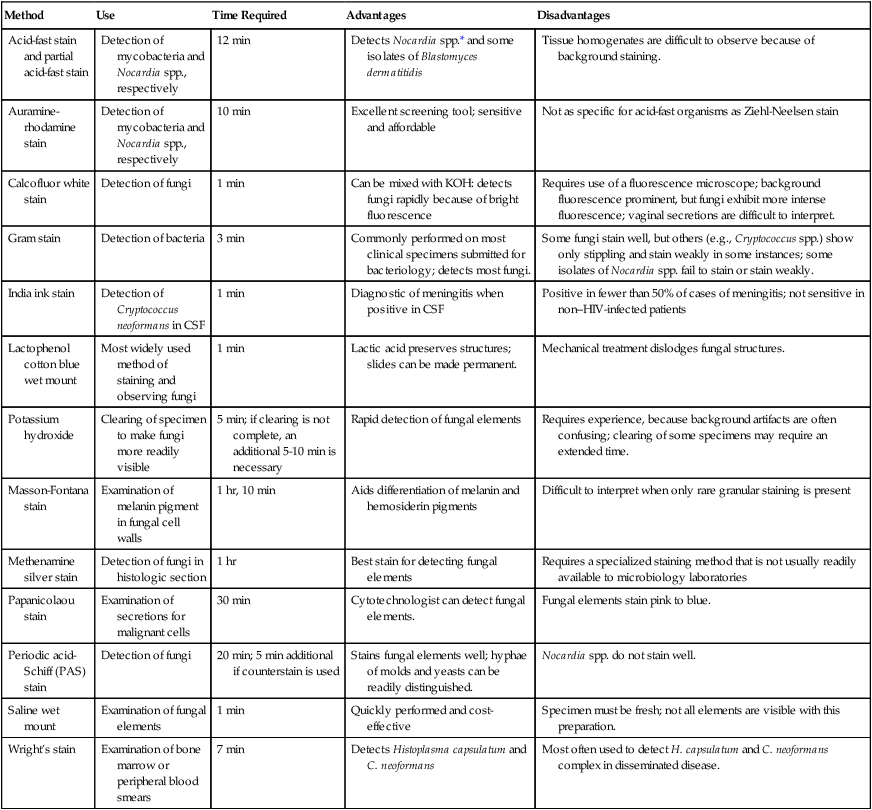

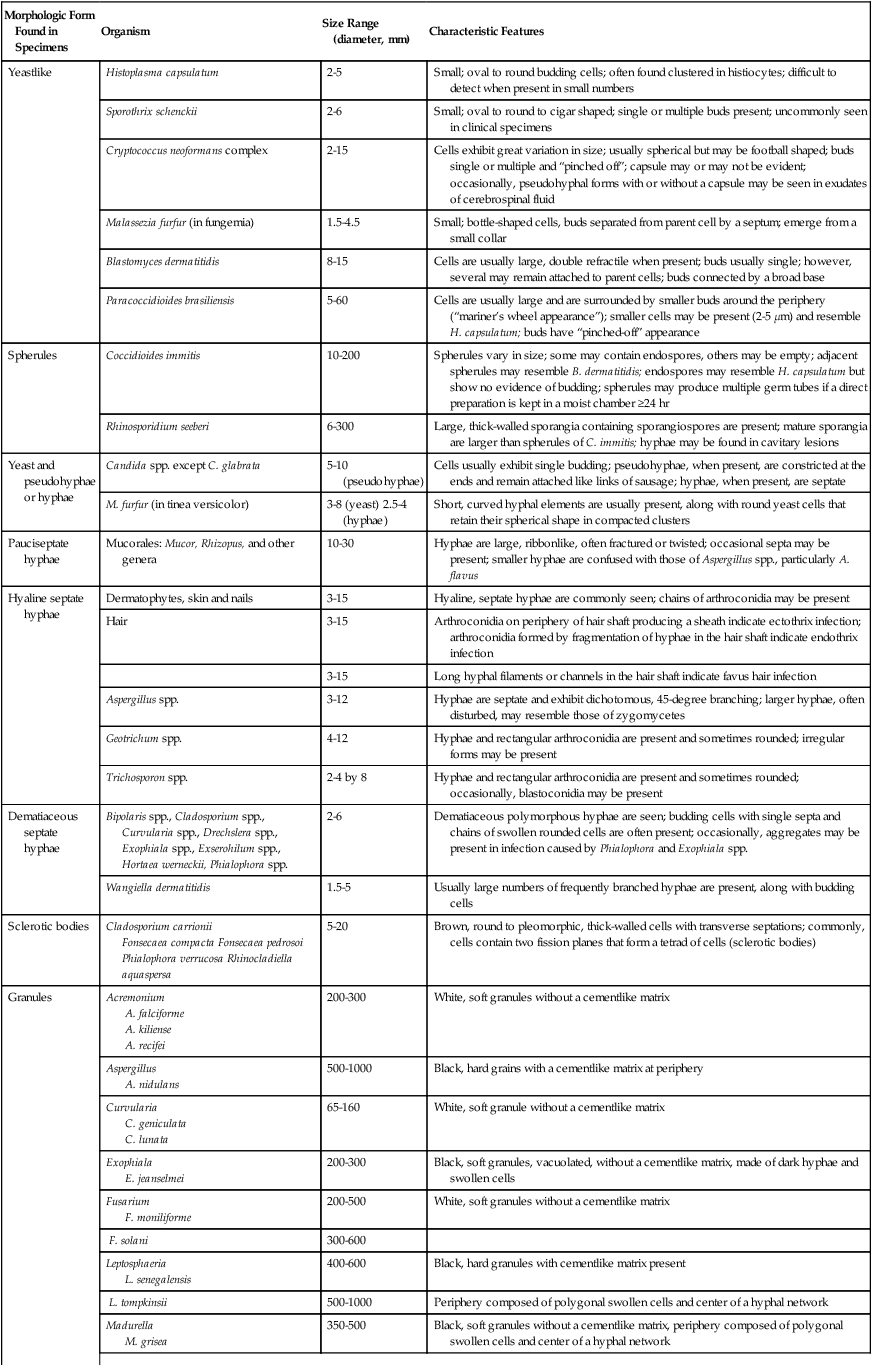

TABLE 59-8

Summary of Characteristic Features of Fungi Seen in Direct Examination of Clinical Specimens

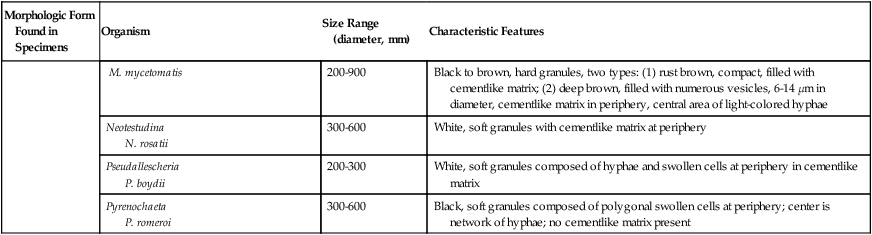

| Morphologic Form Found in Specimens | Organism | Size Range (diameter, mm) | Characteristic Features |

| Yeastlike | Histoplasma capsulatum | 2-5 | Small; oval to round budding cells; often found clustered in histiocytes; difficult to detect when present in small numbers |

| Sporothrix schenckii | 2-6 | Small; oval to round to cigar shaped; single or multiple buds present; uncommonly seen in clinical specimens | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans complex | 2-15 | Cells exhibit great variation in size; usually spherical but may be football shaped; buds single or multiple and “pinched off”; capsule may or may not be evident; occasionally, pseudohyphal forms with or without a capsule may be seen in exudates of cerebrospinal fluid | |

| Malassezia furfur (in fungemia) | 1.5-4.5 | Small; bottle-shaped cells, buds separated from parent cell by a septum; emerge from a small collar | |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | 8-15 | Cells are usually large, double refractile when present; buds usually single; however, several may remain attached to parent cells; buds connected by a broad base | |

| Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | 5-60 | Cells are usually large and are surrounded by smaller buds around the periphery (“mariner’s wheel appearance”); smaller cells may be present (2-5 µm) and resemble H. capsulatum; buds have “pinched-off” appearance | |

| Spherules | Coccidioides immitis | 10-200 | Spherules vary in size; some may contain endospores, others may be empty; adjacent spherules may resemble B. dermatitidis; endospores may resemble H. capsulatum but show no evidence of budding; spherules may produce multiple germ tubes if a direct preparation is kept in a moist chamber ≥24 hr |

| Rhinosporidium seeberi | 6-300 | Large, thick-walled sporangia containing sporangiospores are present; mature sporangia are larger than spherules of C. immitis; hyphae may be found in cavitary lesions | |

| Yeast and pseudohyphae or hyphae | Candida spp. except C. glabrata | 5-10 (pseudohyphae) | Cells usually exhibit single budding; pseudohyphae, when present, are constricted at the ends and remain attached like links of sausage; hyphae, when present, are septate |

| M. furfur (in tinea versicolor) | 3-8 (yeast) 2.5-4 (hyphae) | Short, curved hyphal elements are usually present, along with round yeast cells that retain their spherical shape in compacted clusters | |

| Pauciseptate hyphae | Mucorales: Mucor, Rhizopus, and other genera | 10-30 | Hyphae are large, ribbonlike, often fractured or twisted; occasional septa may be present; smaller hyphae are confused with those of Aspergillus spp., particularly A. flavus |

| Hyaline septate hyphae | Dermatophytes, skin and nails | 3-15 | Hyaline, septate hyphae are commonly seen; chains of arthroconidia may be present |

| Hair | 3-15 | Arthroconidia on periphery of hair shaft producing a sheath indicate ectothrix infection; arthroconidia formed by fragmentation of hyphae in the hair shaft indicate endothrix infection | |

| 3-15 | Long hyphal filaments or channels in the hair shaft indicate favus hair infection | ||

| Aspergillus spp. | 3-12 | Hyphae are septate and exhibit dichotomous, 45-degree branching; larger hyphae, often disturbed, may resemble those of zygomycetes | |

| Geotrichum spp. | 4-12 | Hyphae and rectangular arthroconidia are present and sometimes rounded; irregular forms may be present | |

| Trichosporon spp. | 2-4 by 8 | Hyphae and rectangular arthroconidia are present and sometimes rounded; occasionally, blastoconidia may be present | |

| Dematiaceous septate hyphae | Bipolaris spp., Cladosporium spp., Curvularia spp., Drechslera spp., Exophiala spp., Exserohilum spp., Hortaea werneckii, Phialophora spp. | 2-6 | Dematiaceous polymorphous hyphae are seen; budding cells with single septa and chains of swollen rounded cells are often present; occasionally, aggregates may be present in infection caused by Phialophora and Exophiala spp. |

| Wangiella dermatitidis | 1.5-5 | Usually large numbers of frequently branched hyphae are present, along with budding cells | |

| Sclerotic bodies | Cladosporium carrionii Fonsecaea compacta Fonsecaea pedrosoi Phialophora verrucosa Rhinocladiella aquaspersa |

5-20 | Brown, round to pleomorphic, thick-walled cells with transverse septations; commonly, cells contain two fission planes that form a tetrad of cells (sclerotic bodies) |

| Granules | Acremonium A. falciforme A. kiliense A. recifei |

200-300 | White, soft granules without a cementlike matrix |

| Aspergillus A. nidulans |

500-1000 | Black, hard grains with a cementlike matrix at periphery | |

| Curvularia C. geniculata C. lunata |

65-160 | White, soft granule without a cementlike matrix | |

| Exophiala E. jeanselmei |

200-300 | Black, soft granules, vacuolated, without a cementlike matrix, made of dark hyphae and swollen cells | |

| Fusarium F. moniliforme |

200-500 | White, soft granules without a cementlike matrix | |

| F. solani | 300-600 | ||

| Leptosphaeria L. senegalensis |

400-600 | Black, hard granules with cementlike matrix present | |

| L. tompkinsii | 500-1000 | Periphery composed of polygonal swollen cells and center of a hyphal network | |

| Madurella M. grisea |

350-500 | Black, soft granules without a cementlike matrix, periphery composed of polygonal swollen cells and center of a hyphal network | |

| M. mycetomatis | 200-900 | Black to brown, hard granules, two types: (1) rust brown, compact, filled with cementlike matrix; (2) deep brown, filled with numerous vesicles, 6-14 µm in diameter, cementlike matrix in periphery, central area of light-colored hyphae | |

| Neotestudina N. rosatii |

300-600 | White, soft granules with cementlike matrix at periphery | |

| Pseudallescheria P. boydii |

200-300 | White, soft granules composed of hyphae and swollen cells at periphery in cementlike matrix | |

| Pyrenochaeta P. romeroi |

300-600 | Black, soft granules composed of polygonal swollen cells at periphery; center is network of hyphae; no cementlike matrix present |

Traditionally, the potassium hydroxide preparation has been the recommended method for direct microscopic examination of specimens. However, the calcofluor white stain now is believed to be superior (see Procedure 59-1 on the Evolve site). Slides prepared by this method may be observed using fluorescent or bright-field microscopy, as is used for the potassium hydroxide preparation; the former is optimal, because fungal cells fluoresce.

Serodiagnosis

Molecular Detection

Molecular detection methods are becoming popular in all areas of clinical microbiology; however, none has been accepted as a routine diagnostic tool in clinical mycology. Ideally, a panel of primers specific for the detection of fungi in clinical specimens would include the most common organisms known to cause disease in immunocompromised patients (including the dimorphic fungi and Pneumocystis jiroveci). However, currently no commercial methods are available to the clinical laboratory, and reports in the literature deal predominantly with selected organisms such as the Advan Dx PNA fish for the identification of Cardida spp. from blood cultures (Advan Dx, Woburn, MA). The large number of fungi may limit the development of a cost-effective screening method. Studies by Hopfer,4 Lu et al.,5 Makimura et al.,6 and Sandhu et al.7 present examples of what has been done with molecular methods in mycology for the detection of fungi in clinical specimens.

General Considerations for the Identification of Yeasts

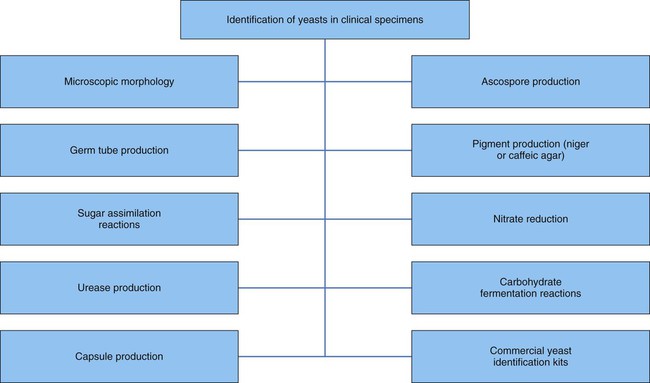

Most often yeasts are identified through the use of a combination of tests (Figure 59-5). Identification factors and techniques include:

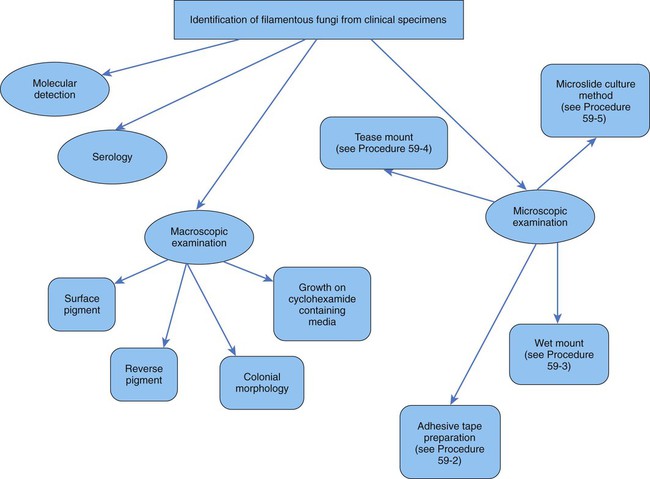

General Considerations for the Identification of Molds

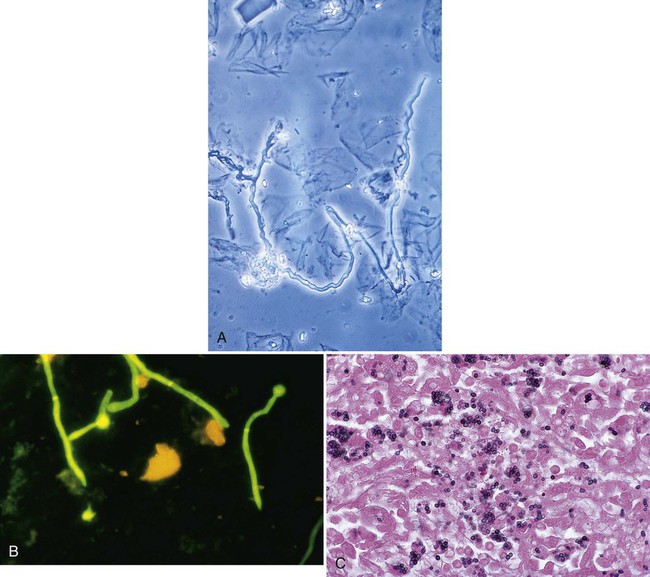

Filamentous fungi are also identified by a combination of tests (Figure 59-6). Molds are identified using a combination of the following:

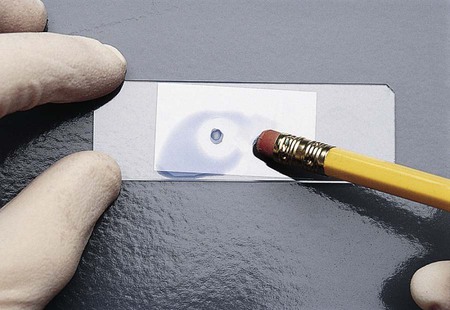

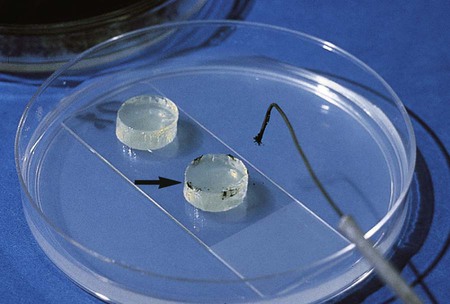

The fungi may be prepared for microscopic observation using several techniques. The procedure traditionally used by most laboratories is the cellophane (Scotch) tape preparation (see Procedure 59-2 on the Evolve site; Figure 59-7). It can be done easily and quickly and often is sufficient to make the identification for most fungi. However, some laboratories prefer the wet mount (see Procedure 59-3 on the Evolve site; Figure 59-8) or tease mount (see Procedure 59-4 on the Evolve site). A microslide culture method (see Procedure 59-5 on the Evolve site; Figure 59-9) may be used when greater detail of the morphologic features is required.

General Morphologic Features of the Molds

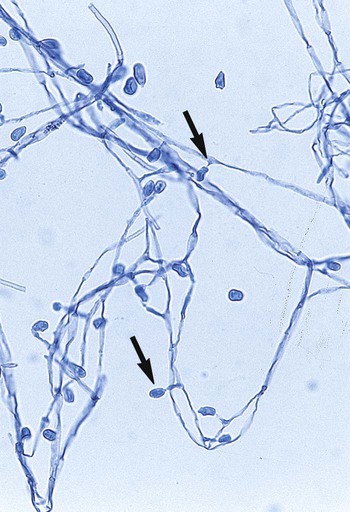

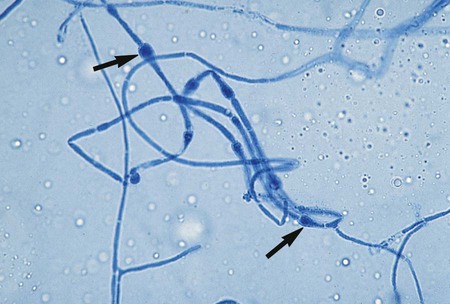

Specialized types of vegetative hyphae may be helpful for categorizing an organism into a certain group. For example, dermatophytes often produce several types of hyphae, including antler hyphae, so named because they are curved, freely branching, and have the appearance of antlers (Figure 59-10). Racquet hyphae are enlarged, club-shaped structures (Figure 59-11). In addition, certain dermatophytes produce spiral hyphae that are coiled or exhibit corkscrewlike turns in the hyphal strand (Figure 59-12). These structures are not characteristic for any certain group; however, they are found most commonly in dermatophytes.

Some species of fungi produce sexual spores in a large, saclike structure called an ascocarp (Figure 59-13). The ascocarp contains smaller sacs, called asci, each of which contains four to eight ascospores. This type of sexual reproduction is not commonly seen in the fungi recovered in the clinical microbiology laboratory; most exhibit only asexual reproduction. It is possible that all fungi have a sexual form, but for some species it has not yet been observed on artificial culture media. Conidia, which are produced by most fungi, represent the asexual reproductive cycle. The type of conidia and their morphology and arrangement are important criteria for definitively identifying an organism (Figure 59-14).

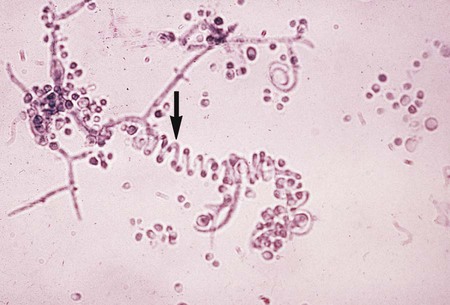

The simplest type of sporulation is the development of a spore directly from the vegetative hyphae. Arthroconidia are formed directly from the hyphae by fragmentation through the points of septation (Figure 59-15). When mature, they appear as square, rectangular, or barrel-shaped, thick-walled cells. These result from the simple fragmentation of the hyphae into spores, which are easily dislodged and disseminated into the environment. Chlamydoconidia (chlamydospores) are round, thick-walled spores formed directly from the differentiation of hyphae in which there is a concentration of protoplasm and nutrient material (Figure 59-16). These appear to be resistant resting spores produced by the rounding up and enlargement of the cells of the hyphae. Chlamydoconidia may be intercalary (within the hyphae) or terminal (on the end of the hyphae).

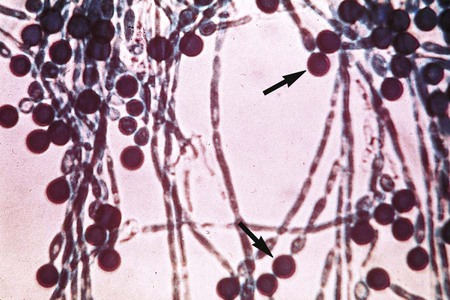

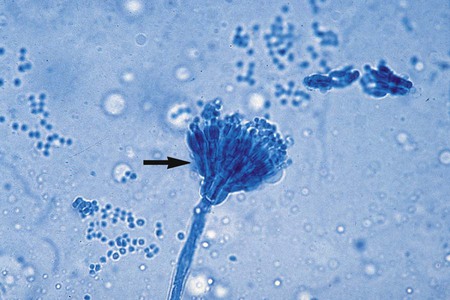

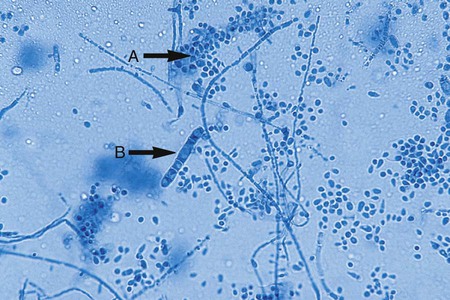

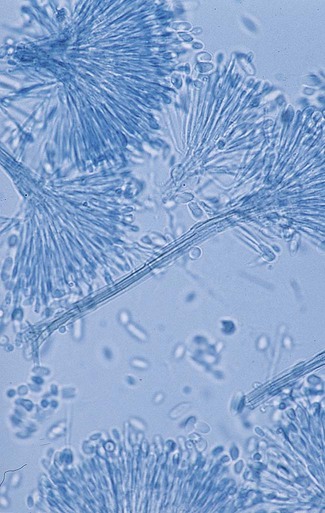

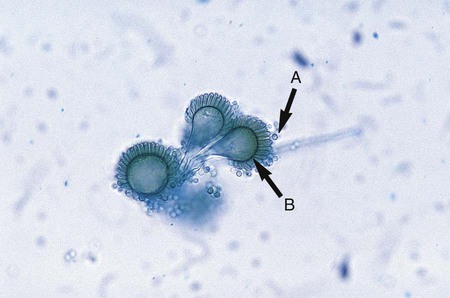

A variety of other types of spores occur with many species of fungi. Conidia are asexual spores produced singly or in groups by specialized hyphal strands, conidiophores. In some instances, the conidia are freed from their point of attachment by pinching off, or abstriction. Some conidiophores terminate in a swollen vesicle. From the surface of the vesicle are formed secondary small, flask-shaped phialides, which in turn give rise to long chains of conidia. This type of fruiting structure is characteristic of the aspergilli. A single, simple, slender, tubular conidiophore (phialide) that produces a cluster of conidia, held together as a gelatinous mass, is characteristic of certain fungi, including the genus Acremonium (Figure 59-17). In other instances, conidiophores form a branching structure called a penicillus, in which each branch terminates in secondary branches (metulae) and phialides, from which chains of conidia are borne (Figure 59-18). Species of Penicillium and Paecilomyces are representative of this type of sporulation. In other instances, fungi may produce conidia of two sizes: microconidia, which are small, unicellular, round, elliptical, or pyriform in shape, or macroconidia, which are large, usually multiseptate, and club or spindle shaped (Figure 59-19). Microconidia may be borne directly on the side of a hyphal strand or at the end of a conidiophore. Macroconidia are usually borne on a short to long conidiophore and may be smooth or rough walled. Microconidia and macroconidia are seen in some fungal species and are not specific, except as they are used to differentiate a limited number of genera.

The hyphae of the mucorales are sparsely septate. Sporulation takes place by progressive cleavage during maturation in the sporangium, a saclike structure produced at the tip of a long stalk (sporangiophore). Sporangiospores (spores produced in the sporangium) are produced and released by the rupture of the sporangial wall (Figure 59-20). In rare cases some isolates may produce zygospores, rough-walled spores produced by the union of two matching types of a mucorales; this is an example of sexual reproduction.

Clinical Relevance for Fungal Identification

The question of when and how far to go with the identification of fungi recovered from clinical specimens presents an interesting challenge. The current emphasis on cost containment and the ever-increasing number of opportunistic fungi causing infection in compromised patients prompts consideration of whether all fungi recovered from clinical specimens should be thoroughly identified and reported. A study by Murray et al.8 focused on the time and expense involved in identifying yeasts from respiratory tract specimens. Because these are the specimens most commonly submitted for fungal culture, the researchers questioned whether identifying every organism recovered was important. After evaluating the clinical usefulness of information provided through the identification of yeast recovered from respiratory tract specimens, they suggested the following:

• Routine identification of yeasts recovered in culture from respiratory secretions is not warranted, but all yeasts should be screened for Cryptococcus neoformans complex.

• All respiratory secretions submitted for fungal culture, regardless of the presence or absence of oropharyngeal contamination, should be cultured, because common pathogens, such as H. capsulatum, B. dermatitidis, C. immitis, and S. schenckii, may be recovered.

• Routine identification of yeast in respiratory secretions has little or no value for the clinician and probably represents “normal flora,” except for C. neoformans.

The extent of identification of yeasts from other specimen sources is discussed in Chapter 63. The usefulness of identification and susceptibility testing of non-Cryptococcus yeast isolates was studied by Barenfenger.9 She found that, compared with only superficial characterization (i.e., “Yeast present, not C. neoformans), identification and susceptibility testing of Candida isolates from respiratory secretions led to unnecessary treatment and increased costs. No statistical difference was seen in the mortality of these groups.

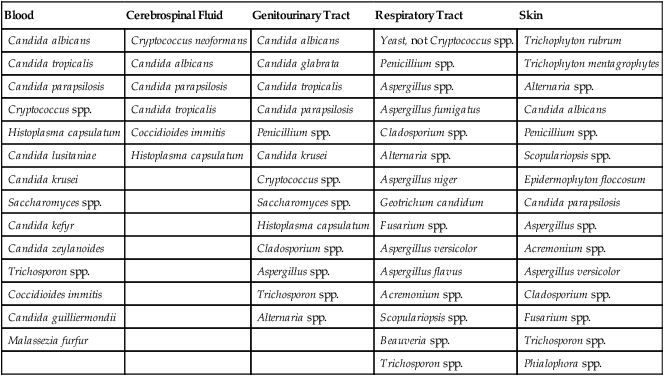

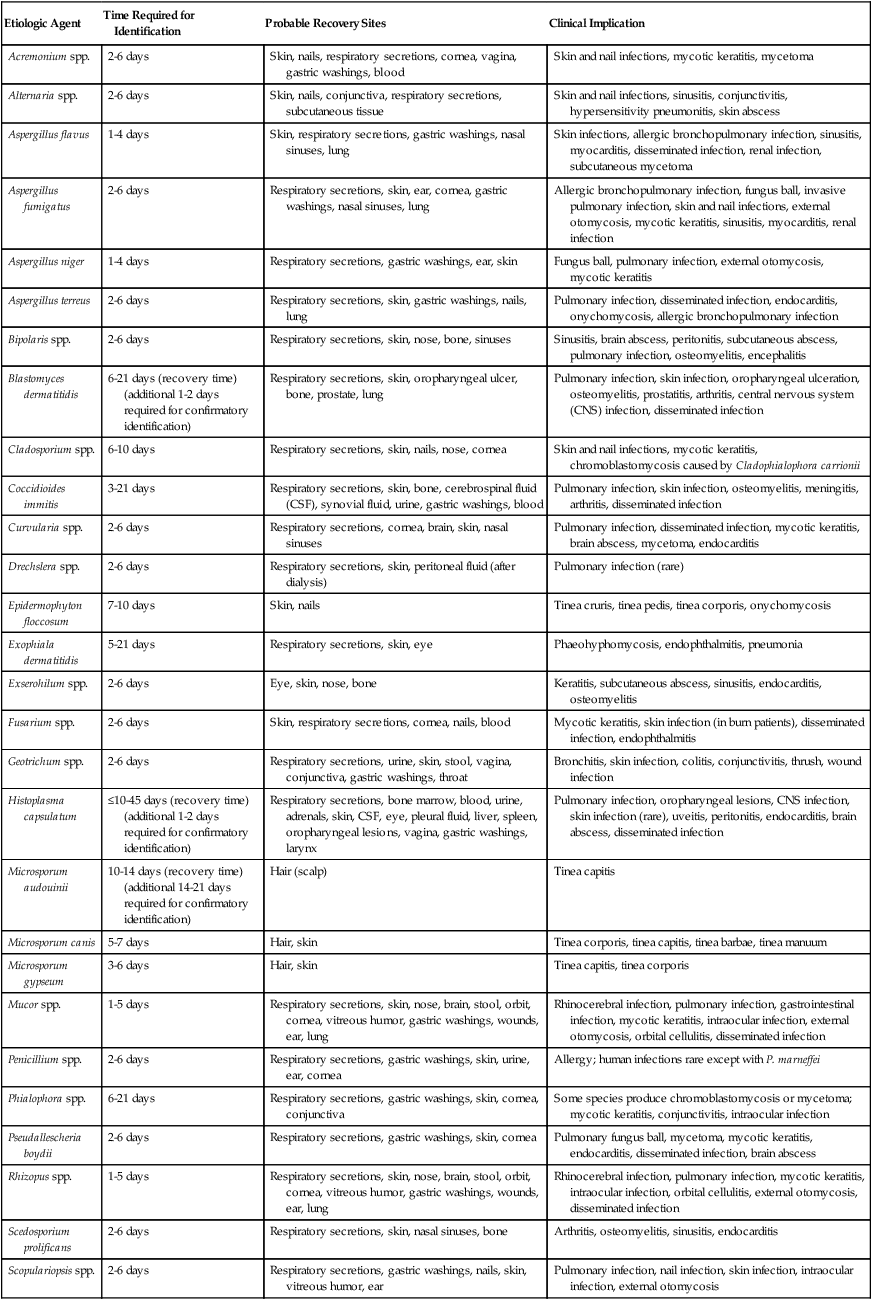

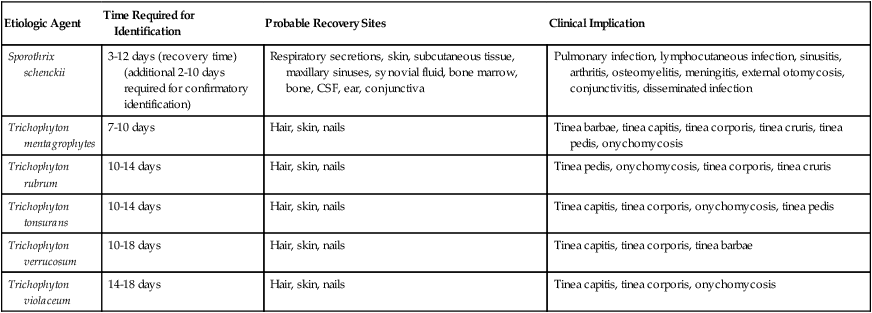

As shown in Table 59-9, an increasing number of fungi may be isolated in the clinical microbiology laboratory. They are considered environmental flora, but in reality must be regarded as potential pathogens because infections with a number of these organisms have been reported. Less commonly encountered fungal pathogens that have been shown to cause human infections include but are not limited to P. boydii; Scedosporium prolificans; Bipolaris, Exserohilum, Trichosporon, and Aureobasidium spp., and others. The laboratory must identify and report all organisms recovered from clinical specimens so that their clinical significance can be determined. In many instances, the presence of environmental fungi is unimportant; however, that is not always the case. Tables 59-10 and 59-11 present the molds and yeasts implicated in causing human infection, the time required for their identification, the most likely site for their recovery, and the clinical implications of each.

TABLE 59-9

Fungi Most Commonly Recovered from Clinical Specimens

| Blood | Cerebrospinal Fluid | Genitourinary Tract | Respiratory Tract | Skin |

| Candida albicans | Cryptococcus neoformans | Candida albicans | Yeast, not Cryptococcus spp. | Trichophyton rubrum |

| Candida tropicalis | Candida albicans | Candida glabrata | Penicillium spp. | Trichophyton mentagrophytes |

| Candida parapsilosis | Candida parapsilosis | Candida tropicalis | Aspergillus spp. | Alternaria spp. |

| Cryptococcus spp. | Candida tropicalis | Candida parapsilosis | Aspergillus fumigatus | Candida albicans |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Coccidioides immitis | Penicillium spp. | Cladosporium spp. | Penicillium spp. |

| Candida lusitaniae | Histoplasma capsulatum | Candida krusei | Alternaria spp. | Scopulariopsis spp. |

| Candida krusei | Cryptococcus spp. | Aspergillus niger | Epidermophyton floccosum | |

| Saccharomyces spp. | Saccharomyces spp. | Geotrichum candidum | Candida parapsilosis | |

| Candida kefyr | Histoplasma capsulatum | Fusarium spp. | Aspergillus spp. | |

| Candida zeylanoides | Cladosporium spp. | Aspergillus versicolor | Acremonium spp. | |

| Trichosporon spp. | Aspergillus spp. | Aspergillus flavus | Aspergillus versicolor | |

| Coccidioides immitis | Trichosporon spp. | Acremonium spp. | Cladosporium spp. | |

| Candida guilliermondii | Alternaria spp. | Scopulariopsis spp. | Fusarium spp. | |

| Malassezia furfur | Beauveria spp. | Trichosporon spp. | ||

| Trichosporon spp. | Phialophora spp. |

TABLE 59-10

Common Filamentous Fungi Implicated in Human Mycotic Infections

| Etiologic Agent | Time Required for Identification | Probable Recovery Sites | Clinical Implication |

| Acremonium spp. | 2-6 days | Skin, nails, respiratory secretions, cornea, vagina, gastric washings, blood | Skin and nail infections, mycotic keratitis, mycetoma |

| Alternaria spp. | 2-6 days | Skin, nails, conjunctiva, respiratory secretions, subcutaneous tissue | Skin and nail infections, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, skin abscess |

| Aspergillus flavus | 1-4 days | Skin, respiratory secretions, gastric washings, nasal sinuses, lung | Skin infections, allergic bronchopulmonary infection, sinusitis, myocarditis, disseminated infection, renal infection, subcutaneous mycetoma |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, ear, cornea, gastric washings, nasal sinuses, lung | Allergic bronchopulmonary infection, fungus ball, invasive pulmonary infection, skin and nail infections, external otomycosis, mycotic keratitis, sinusitis, myocarditis, renal infection |

| Aspergillus niger | 1-4 days | Respiratory secretions, gastric washings, ear, skin | Fungus ball, pulmonary infection, external otomycosis, mycotic keratitis |

| Aspergillus terreus | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, gastric washings, nails, lung | Pulmonary infection, disseminated infection, endocarditis, onychomycosis, allergic bronchopulmonary infection |

| Bipolaris spp. | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, nose, bone, sinuses | Sinusitis, brain abscess, peritonitis, subcutaneous abscess, pulmonary infection, osteomyelitis, encephalitis |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | 6-21 days (recovery time) (additional 1-2 days required for confirmatory identification) | Respiratory secretions, skin, oropharyngeal ulcer, bone, prostate, lung | Pulmonary infection, skin infection, oropharyngeal ulceration, osteomyelitis, prostatitis, arthritis, central nervous system (CNS) infection, disseminated infection |

| Cladosporium spp. | 6-10 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, nails, nose, cornea | Skin and nail infections, mycotic keratitis, chromoblastomycosis caused by Cladophialophora carrionii |

| Coccidioides immitis | 3-21 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, bone, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), synovial fluid, urine, gastric washings, blood | Pulmonary infection, skin infection, osteomyelitis, meningitis, arthritis, disseminated infection |

| Curvularia spp. | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, cornea, brain, skin, nasal sinuses | Pulmonary infection, disseminated infection, mycotic keratitis, brain abscess, mycetoma, endocarditis |

| Drechslera spp. | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, peritoneal fluid (after dialysis) | Pulmonary infection (rare) |

| Epidermophyton floccosum | 7-10 days | Skin, nails | Tinea cruris, tinea pedis, tinea corporis, onychomycosis |

| Exophiala dermatitidis | 5-21 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, eye | Phaeohyphomycosis, endophthalmitis, pneumonia |

| Exserohilum spp. | 2-6 days | Eye, skin, nose, bone | Keratitis, subcutaneous abscess, sinusitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis |

| Fusarium spp. | 2-6 days | Skin, respiratory secretions, cornea, nails, blood | Mycotic keratitis, skin infection (in burn patients), disseminated infection, endophthalmitis |

| Geotrichum spp. | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, urine, skin, stool, vagina, conjunctiva, gastric washings, throat | Bronchitis, skin infection, colitis, conjunctivitis, thrush, wound infection |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | ≤10-45 days (recovery time) (additional 1-2 days required for confirmatory identification) | Respiratory secretions, bone marrow, blood, urine, adrenals, skin, CSF, eye, pleural fluid, liver, spleen, oropharyngeal lesions, vagina, gastric washings, larynx | Pulmonary infection, oropharyngeal lesions, CNS infection, skin infection (rare), uveitis, peritonitis, endocarditis, brain abscess, disseminated infection |

| Microsporum audouinii | 10-14 days (recovery time) (additional 14-21 days required for confirmatory identification) | Hair (scalp) | Tinea capitis |

| Microsporum canis | 5-7 days | Hair, skin | Tinea corporis, tinea capitis, tinea barbae, tinea manuum |

| Microsporum gypseum | 3-6 days | Hair, skin | Tinea capitis, tinea corporis |

| Mucor spp. | 1-5 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, nose, brain, stool, orbit, cornea, vitreous humor, gastric washings, wounds, ear, lung | Rhinocerebral infection, pulmonary infection, gastrointestinal infection, mycotic keratitis, intraocular infection, external otomycosis, orbital cellulitis, disseminated infection |

| Penicillium spp. | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, gastric washings, skin, urine, ear, cornea | Allergy; human infections rare except with P. marneffei |

| Phialophora spp. | 6-21 days | Respiratory secretions, gastric washings, skin, cornea, conjunctiva | Some species produce chromoblastomycosis or mycetoma; mycotic keratitis, conjunctivitis, intraocular infection |

| Pseudallescheria boydii | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, gastric washings, skin, cornea | Pulmonary fungus ball, mycetoma, mycotic keratitis, endocarditis, disseminated infection, brain abscess |

| Rhizopus spp. | 1-5 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, nose, brain, stool, orbit, cornea, vitreous humor, gastric washings, wounds, ear, lung | Rhinocerebral infection, pulmonary infection, mycotic keratitis, intraocular infection, orbital cellulitis, external otomycosis, disseminated infection |

| Scedosporium prolificans | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, skin, nasal sinuses, bone | Arthritis, osteomyelitis, sinusitis, endocarditis |

| Scopulariopsis spp. | 2-6 days | Respiratory secretions, gastric washings, nails, skin, vitreous humor, ear | Pulmonary infection, nail infection, skin infection, intraocular infection, external otomycosis |

| Sporothrix schenckii | 3-12 days (recovery time) (additional 2-10 days required for confirmatory identification) | Respiratory secretions, skin, subcutaneous tissue, maxillary sinuses, synovial fluid, bone marrow, bone, CSF, ear, conjunctiva | Pulmonary infection, lymphocutaneous infection, sinusitis, arthritis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, external otomycosis, conjunctivitis, disseminated infection |

| Trichophyton mentagrophytes | 7-10 days | Hair, skin, nails | Tinea barbae, tinea capitis, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea pedis, onychomycosis |

| Trichophyton rubrum | 10-14 days | Hair, skin, nails | Tinea pedis, onychomycosis, tinea corporis, tinea cruris |

| Trichophyton tonsurans | 10-14 days | Hair, skin, nails | Tinea capitis, tinea corporis, onychomycosis, tinea pedis |

| Trichophyton verrucosum | 10-18 days | Hair, skin, nails | Tinea capitis, tinea corporis, tinea barbae |

| Trichophyton violaceum | 14-18 days | Hair, skin, nails | Tinea capitis, tinea corporis, onychomycosis |

TABLE 59-11

Common Yeastlike Organisms Implicated in Human Infection*

| Etiologic Agent | Probable Recovery Sites | Clinical Implication |

| Candida albicans | Respiratory secretions, vagina, urine, skin, oropharynx, gastric washings, blood, stool, transtracheal aspiration, cornea, nails, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), bone, peritoneal fluid | Pulmonary infection, vaginitis, urinary tract infection, dermatitis, fungemia, mycotic keratitis, onychomycosis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, peritonitis, myocarditis, endocarditis, endophthalmitis, disseminated infection, thrush, arthritis |

| Candida glabrata | Respiratory secretions, urine, vagina, gastric washings, blood, skin, oropharynx, transtracheal aspiration, stool, bone marrow, skin (rare) | Pulmonary infection, urinary tract infection, vaginitis, fungemia, disseminated infection, endocarditis |

| Candida tropicalis | Respiratory secretions, urine, gastric washings, vagina, blood, skin, oropharynx, transtracheal aspiration, stool, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, cornea | Pulmonary infection, vaginitis, thrush, endophthalmitis, endocarditis, arthritis, peritonitis, mycotic keratitis, fungemia |

| Candida parapsilosis | Respiratory secretions, urine, gastric washings, blood, vagina, oropharynx, skin, transtracheal aspiration, stool, pleural fluid, ear, nails | Endophthalmitis, endocarditis, vaginitis, mycotic keratitis, external otomycosis, paronychia, fungemia |

| Saccharomyces spp. | Respiratory secretions, urine, gastric washings, vagina, skin, oropharynx, transtracheal aspiration, stool, blood | Pulmonary infection (rare), endocarditis |

| Candida krusei | Respiratory secretions, urine, gastric washings, vagina, skin, oropharynx, blood, transtracheal aspiration, stool, cornea | Endocarditis, vaginitis, urinary tract infection, mycotic keratitis |

| Candida guilliermondii | Respiratory secretions, gastric washings, vagina, skin, nails, oropharynx, blood, cornea, bone, urine | Endocarditis, fungemia, dermatitis, onychomycosis, mycotic keratitis, osteomyelitis, urinary tract infection |

| Rhodotorula spp. | Respiratory secretions, urine, gastric washings, blood, vagina, skin, oropharynx, stool, CSF, cornea | Fungemia, endocarditis, mycotic keratitis |

| Trichosporon spp. | Respiratory secretions, blood, skin, oropharynx, stool | Pulmonary infection, brain abscess, disseminated infection, piedra |

| Cryptococcus species complex (C. neoformans, var. neoformans; C. neoformans, var. grubii, C. gatti) | Respiratory secretions, CSF, bone, blood, bone marrow, urine, skin, pleural fluid, gastric washings, transtracheal aspiration, cornea, orbit, vitreous humor | Pulmonary infection, meningitis, osteomyelitis, fungemia, disseminated infection, endocarditis, skin infection, mycotic keratitis, orbital cellulitis, endophthalmic infection |

| Cryptococcus albidus subsp. albidus | Respiratory secretions, skin, gastric washings, urine, cornea | Meningitis, pulmonary infection |

| Candida kefyr (pseudotropicalis) | Respiratory secretions, vagina, urine, gastric washings, oropharynx | Vaginitis, urinary tract infection |

| Cryptococcus luteolus | Respiratory secretions, skin, nose | Not commonly implicated in human infection |

| Cryptococcus laurentii | Respiratory secretions, CSF, skin, oropharynx, stool | Not commonly implicated in human infection |

| Cryptococcus albidus subsp. diffluens | Respiratory secretions, urine, CSF, gastric washings, skin | Not commonly implicated in human infection |

| Cryptococcus terreus | Respiratory secretions, skin, nose | Not commonly implicated in human infection |