Chapter 6 Overview and Assessment of Variability

Biopsychosocial Models of Development

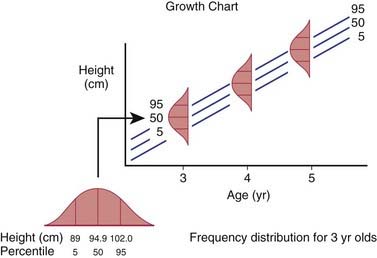

The biologic model of medicine presumes that a patient presents with signs and symptoms of a disease and a physician focuses on diseases of the body. This model neglects the psychologic aspect of a person who exists in the larger realm of the family and society. In the biopsychosocial model, higher-level systems are simultaneously considered with the lower-level systems that make up the person and the person’s environment (Fig. 6-1). A patient’s symptoms are examined and explained in the context of the patient’s existence. This basic model can be used to understand health and both acute and chronic disease.

Figure 6-1 Continuum and hierarchy of natural systems in the biopsychosocial model.

(From Engel GL: The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model, Am J Psychiatry 137:535–544, 1980.)

Biologic Influences

Temperament describes the stable, early-appearing individual variations in behavioral dimensions including emotionality (crying, laughing, sulking), activity level, attention, sociability, and persistence. The classic theory of Thomas and Chess proposes 9 dimensions of temperament (Table 6-1). These characteristics lead to 3 common constellations: (1) the easy, highly adaptable child, who has regular biologic cycles; (2) the difficult child, who withdraws from new stimuli and is easily frustrated; and (3) the slow-to-warm-up child, who needs extra time to adapt to new circumstances. Various combinations of these clusters also occur. Temperament has long been described as biologic or “inherited,” largely based on parent reports (although confirmed by some independent observational studies) of twins. Monozygotic twins are rated by their parents as temperamentally similar more often than are dizygotic twins. Estimates of heritability suggest that genetic differences account for approximately 20-60% of the variability of temperament within a population. It had been presumed that the remaining 80-40% of the variance was environmentally influenced because genetic influences tended to be viewed as static. We now know that genes are dynamic, changing in the quantity and quality of their effects as a child ages and thus, like environment, may continue to change. Longitudinal twin studies of adult personality indicate that personality changes largely result from non-shared environmental influences, whereas stability of temperament appears to result from genetic factors. Although associations between specific genes and temperament have been noted (a 48-base pair repeat in exon 3 of DRD4 has been associated with novelty seeking), such associations require replication studies before they can be viewed as causative.

Table 6-1 TEMPERAMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS: DESCRIPTIONS AND EXAMPLES*

| CHARACTERISTIC | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLES† |

|---|---|---|

| Activity level | Amount of gross motor movement | “She’s constantly on the move.” “He would rather sit still than run around.” |

| Rhythmicity | Regularity of biologic cycles | “He’s never hungry at the same time each day.” “You could set a watch by her nap.” |

| Approach and withdrawal | Initial response to new stimuli | “She rejects every new food at first.” “He sleeps well in any place.” |

| Adaptability | Ease of adaptation to novel stimulus | “Changes upset him.” “She adjusts to new people quickly.” |

| Threshold of responsiveness | Intensity of stimuli needed to evoke a response (e.g., touch, sound, light) | “He notices all the lumps in his food and objects to them.” “She will eat anything, wear anything, do anything.” |

| Intensity of reaction | Energy level of response | “She shouts when she is happy and wails when she is sad.” “He never cries much.” |

| Quality of mood | Usual disposition (e.g., pleasant, glum) | “He does not laugh much.” “It seems like she is always happy.” |

| Distractibility | How easily diverted from ongoing activity | “She is distracted at mealtime when other children are nearby.” “He doesn’t even hear me when he is playing.” |

| Attention span and persistence | How long a child pays attention and sticks with difficult tasks | “He goes from toy to toy every minute.” “She will keep at a puzzle until she has mastered it.” |

* Based on Chess S, Thomas A: Temperament in clinical practice, New York, 1986, Guilford.

† Typical statements of parents, reflecting the range for each characteristic from very little to very much.

Unifying Concepts: The Transactional Model, Risk, and Resilience

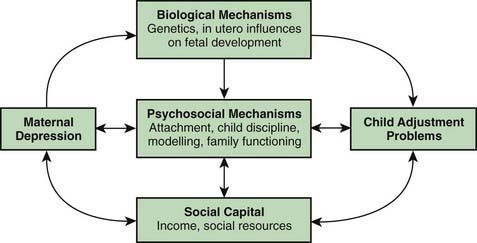

The transactional model proposes that a child’s status at any point in time is a function of the interaction between biologic and social influences. The influences are bidirectional: Biologic factors, such as temperament and health status, both affect the child-rearing environment and are affected by it. A premature infant may cry little and sleep for long periods; the infant’s depressed parent may welcome this good behavior, setting up a cycle that leads to poor nutrition and inadequate growth. The child’s failure to thrive may reinforce the parent’s sense of failure as a parent. At a later stage, impulsivity and inattention associated with early, prolonged undernutrition may lead to aggressive behavior. The cause of the aggression in this case is not the prematurity, the undernutrition, or the maternal depression, but the interaction of all these factors (Fig. 6-2). Conversely, children with biologic risk factors may nevertheless do well developmentally if the child-rearing environment is supportive. Premature infants with electroencephalographic evidence of neurologic immaturity may be at increased risk for cognitive delay. This risk may only be realized when the quality of parent-child interaction is poor. When parent-child interactions are optimal, prematurity carries a reduced risk of developmental disability.

Figure 6-2 Theoretical model of mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment.

(From Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, et al: Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems, Clin Psychol Rev 24:441–459, 2004.)

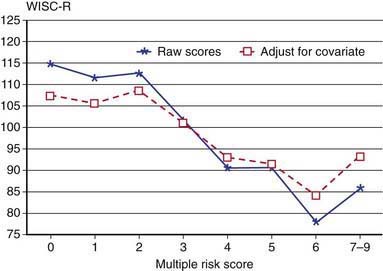

An estimate of developmental risk can begin with a tally of risk factors, such as low income, limited parental education, and lack of neighborhood resources. There is a direct relationship between developmental outcome at age 13 yr and the number of social and family risk factors at age 4 yr (Fig. 6-3). Protective (resilience) factors must also be considered. These factors, like risk factors, may be either biologic (temperamental persistence, athletic talent) or social. The personal histories of children who overcome poverty often include at least one trusted adult (parent, grandparent, teacher) with whom the child has a special, supportive, close relationship.

Developmental Domains and Theories of Emotion and Cognition

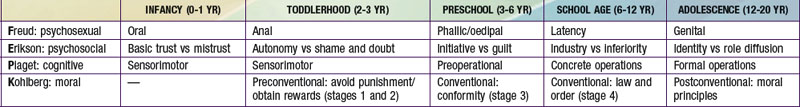

The concept of a developmental line implies that a child passes through successive stages. Several psychoanalytic theories are based on stages as qualitatively different epochs in the development of emotion and cognition (Table 6-2). In contrast, behavioral theories rely less on qualitative change and more on the gradual modification of behavior and accumulation of competence.

Psychoanalytic Theories

At the core of Freudian theory is the idea of body-centered (or, broadly, “sexual”) drives. The focus of the drives shifts with maturation from oral satisfactions (sucking in the 1st yr of life), to anal sensations (holding on and letting go during the toddler years), oedipal drives (possessiveness toward a parent in the preschool years), and genital drives (in puberty and beyond) (see Table 6-2). At each stage, the child’s drive can potentially conflict with the rules of society. Infants may want to suck longer than the mother wants to nurse, or toddlers may decide that they like making a mess. The emotional health of both the child and the adult depends on adequate resolution of these conflicts. Freud saw middle childhood as a period of latency, when the sexual drive is redirected (sublimated) to the achievement of social or external goals.

Erikson’s chief contribution was to recast Freud’s stages in terms of the emerging personality (see Table 6-2). The child’s sense of basic trust develops through the successful negotiation of infantile needs, corresponding to Freud’s oral period. As children progress through these psychosocial stages, different issues become salient. Thus, it is predictable that a toddler will be preoccupied with establishing a sense of autonomy, whereas a late adolescent may be more focused on establishing meaningful relationships and an occupational identity. Erikson recognized that these stages arise in the context of Western European societal expectations; in other cultures, the salient issues may be quite different.

Cognitive Theories

Cognitive development is best understood through the work of Piaget. A central tenet of Piaget’s work is that cognition changes in quality, not just quantity (see Table 6-2). During the sensorimotor stage, an infant’s thinking is tied to immediate sensations and a child’s ability to manipulate objects. The concept of “in” is embodied in a child’s act of putting a block into a cup. With the arrival of language, the nature of thinking changes dramatically; symbols increasingly take the place of objects and actions. Piaget described how children actively construct knowledge for themselves through the linked processes of assimilation (taking in new experiences according to existing schemata) and accommodation (creating new patterns of understanding to adapt to new information). In this way, children are continually and actively reorganizing cognitive processes.

Behavioral Theory

This theoretical perspective distinguishes itself by its lack of concern with a child’s inner experience. Its sole focus is on observable behaviors and measurable factors that either increase or decrease the frequency with which these behaviors occur. No stages are implied; children, adults, and indeed animals all respond in the same way. In its simplest form, the behaviorist orientation asserts that behaviors that are positively reinforced occur more frequently; behaviors that are negatively reinforced or ignored occur less frequently. The strengths of this position are its simplicity, wide applicability, and conduciveness to scientific verification. A behavioral approach lends itself to interventions for various common problems, such as temper tantrums and aggressive preschool behavior, in which behaviors are broken down into discrete units. In cognitively limited children and children with autism spectrum disorders, behavioral interventions using applied behavior analysis (ABA) approaches have demonstrated their ability to teach new, complex behaviors. ABA has been particularly useful in the treatment of early diagnosed autism (Chapter 28.1). However, in cases in which misbehavior is symptomatic of an underlying emotional, perceptual, or family problem, an exclusive reliance on behavior therapy risks leaving the cause untreated. Behavioral approaches can be taught to parents to apply at home.

Theories Commonly Employed in Behavioral Interventions

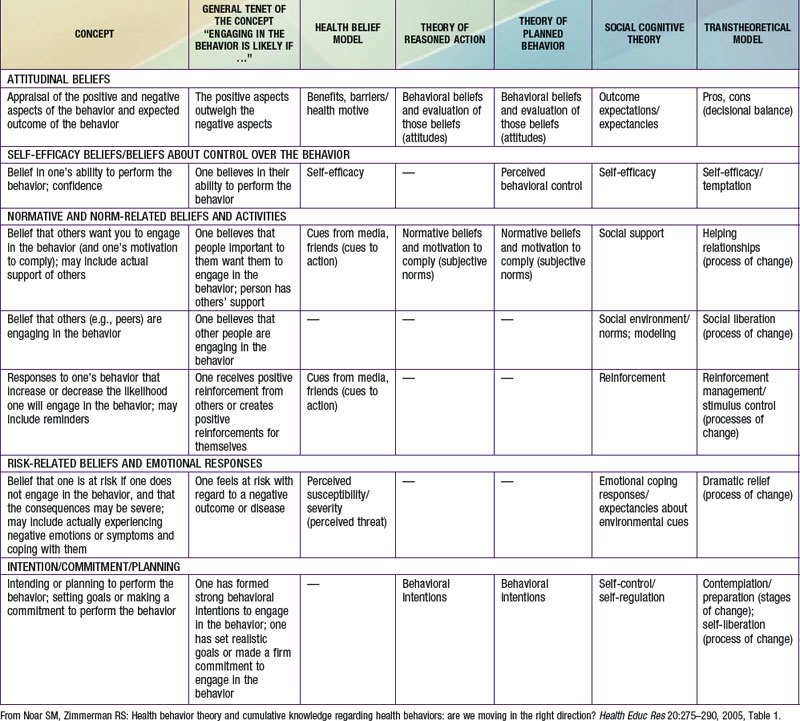

During the past few decades an increasing number of programs (within and outside of the physician’s office) designed to influence behavior have been based on theoretical models of behavior. Some of these models are based on behavioral or cognitive theory or in cases have attributes of both. The most commonly employed models are the Health Belief Model, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Cognitive Theory, and the Transtheoretical Model, also known as Stages of Change Theory. Pediatricians should be aware of these models; similarities and differences between these models are shown in Table 6-3. Motivational interviewing is less a theory of behavior and more a technique to bring about behavior change. The goal in using the technique is to enhance an individual’s motivation to change behavior by exploring and removing ambivalence. This may be practiced by an individual practitioner and is being taught in some pediatric residency programs. Motivational interviewing emphasizes the importance of the therapist (pediatrician) understanding the client’s perspective and displaying unconditional support. The therapist is a partner rather than an authority figure and recognizes that ultimately the patient has control over his or her choices.

Statistics Used in Describing Growth and Development (Chapters 13 and 14)

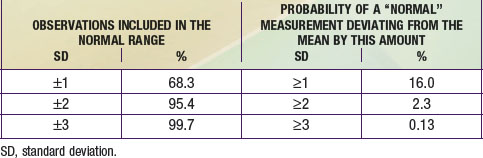

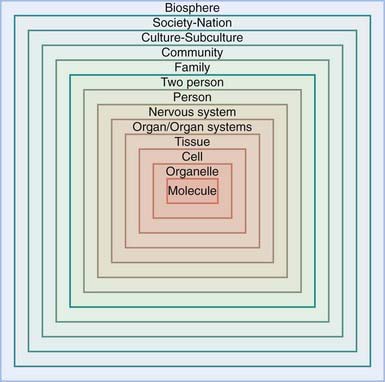

The extent to which observed values cluster near the mean determines the width of the bell and can be described mathematically by the standard deviation (SD). In the ideal normal curve, a range of values extending from 1 SD below the mean to 1 SD above the mean includes approximately 68% of the values, and each “tail” above and below that range contains 16% of the values. A range encompassing ±2 SD includes 95% of the values (with the upper and lower tails each comprising approximately 2.5% of the values), and ±3 SD encompasses 99.7% of the values (Table 6-4 and Fig. 6-4).

Another way of relating an individual to a group uses percentiles. The percentile is the percentage of individuals in the group who have achieved a certain measured quantity (e.g., a height of 95 cm) or a developmental milestone (e.g., walking independently). For anthropometric data, the percentile cutoffs can be calculated from the mean and SD. The 5th, 10th, and 25th percentiles correspond to −1.65 SD, −1.3 SD, and −0.7 SD, respectively. Figure 6-4 demonstrates how frequency distributions of a particular parameter (height) at different ages relate to the percentile lines on the growth curve.

Arkowitz H, Westra HA. Introduction to the special series on motivational interviewing and psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:1149-1155.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. 1977, pp 2–13

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Carey WB. Teaching parents about infant temperament. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1311-1316.

Duncan GJ, Magnuson KA. Can family socioeconomic resources account for racial and ethnic test score gaps? Future Child. 2005;15:35-54.

Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. Am Psychol. 2004;59:77-92.

Frankowski BL, Leader IC, Duncan PM. Strength-based interviewing. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2009;20:22-40. vii–viii

Johnston MV. Plasticity in the developing brain: implications for rehabilitation. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:94-101.

Keverne EB. Understanding well-being in the evolutionary context of brain development. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Soc. 2004;359:1349-1358.

Noar SM, Zimmerman RS. Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ Res. 2005;20:275-290.

Saudino KJ. Behavioral genetics and child temperament. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:214-223.

Shonkoff J, Phillips D. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine: From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

Walker SP, Wachs TD, Gardner JM, et al. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:145-157.

6.1 Assessment of Fetal Growth and Development

Somatic Development

Embryonic Period

Milestones of prenatal development are presented in Table 6-5. By 6 days postconceptual age, as implantation begins, the embryo consists of a spherical mass of cells with a central cavity (the blastocyst). By 2 wk, implantation is complete and the uteroplacental circulation has begun; the embryo has 2 distinct layers, endoderm and ectoderm, and the amnion has begun to form. By 3 wk, the 3rd primary germ layer (mesoderm) has appeared, along with a primitive neural tube and blood vessels. Paired heart tubes have begun to pump.

| WK | DEVELOPMENTAL EVENTS |

|---|---|

| 1 | Fertilization and implantation; beginning of embryonic period |

| 2 | Endoderm and ectoderm appear (bilaminar embryo) |

| 3 | First missed menstrual period; mesoderm appears (trilaminar embryo); somites begin to form |

| 4 | Neural folds fuse; folding of embryo into human-like shape; arm and leg buds appear; crown-rump length 4-5 mm |

| 5 | Lens placodes, primitive mouth, digital rays on hands |

| 6 | Primitive nose, philtrum, primary palate |

| 7 | Eyelids begin; crown-rump length 2 cm |

| 8 | Ovaries and testes distinguishable |

| 9 | Fetal period begins; crown-rump length 5 cm; weight 8 g |

| 12 | External genitals distinguishable |

| 20 | Usual lower limit of viability; weight 460 g; length 19 cm |

| 25 | Third trimester begins; weight 900 g; length 24 cm |

| 28 | Eyes open; fetus turns head down; weight 1,000-1,300 g |

| 38 | Term |

Fetal Period

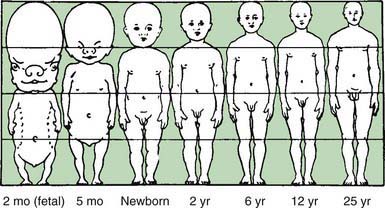

From the 9th wk on (fetal period), somatic changes consist of rapid body growth as well as differentiation of tissues, organs, and organ systems. Changes in body proportion are depicted in Figure 6-5. By wk 10, the face is recognizably human. The midgut returns to the abdomen from the umbilical cord, rotating counterclockwise to bring the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine into their normal positions. By wk 12, the gender of the external genitals becomes clearly distinguishable. Lung development proceeds, with the budding of bronchi, bronchioles, and successively smaller divisions. By wk 20-24, primitive alveoli have formed and surfactant production has begun; before that time, the absence of alveoli renders the lungs useless as organs of gas exchange.

Neurologic Development

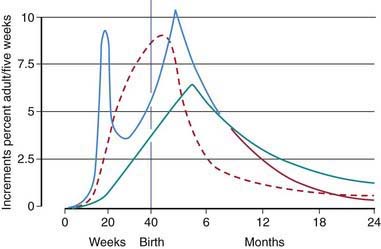

By the end of the embryonic period (wk 8), the gross structure of the nervous system has been established. On a cellular level, neurons migrate outward to form the 6 cortical layers. Migration is complete by the 6th mo, but differentiation continues. Axons and dendrites form synaptic connections at a rapid pace, making the CNS vulnerable to teratogenic or hypoxic influences throughout gestation. Rates of increase in DNA (a marker of cell number), overall brain weight, and cholesterol (a marker of myelinization) are shown in Figure 6-6. The prenatal and postnatal peaks of DNA probably represent rapid growth of neurons and glia, respectively. By the time of birth, the structure of the brain is complete. Synapses will be pruned back substantially and new connections will be made, largely as a result of experience.

Behavioral Development

During the 3rd trimester, fetuses respond to external stimuli with heart rate elevation and body movements (Chapter 90). As with infants in the postnatal period, reactivity to auditory (vibroacoustic) and visual (bright light) stimuli vary depending on their behavioral state, which can be characterized as quiet sleep, active sleep, or awake. Individual differences in the level of fetal activity are commonly noted by mothers and have been observed ultrasonographically. Fetal behavior is affected by maternal medications and diet, increasing after ingestion of caffeine. Behavior may be entrained to the mother’s diurnal rhythms: asleep during the day, active at night.

Threats to Fetal Development

Mortality and morbidity are highest during the prenatal period (Chapter 87). An estimated 50% of all pregnancies end in spontaneous abortion, including approximately 10-25% of all clinically recognized pregnancies. The vast majority occur in the 1st trimester. Some occur as a result of chromosomal or other abnormalities.

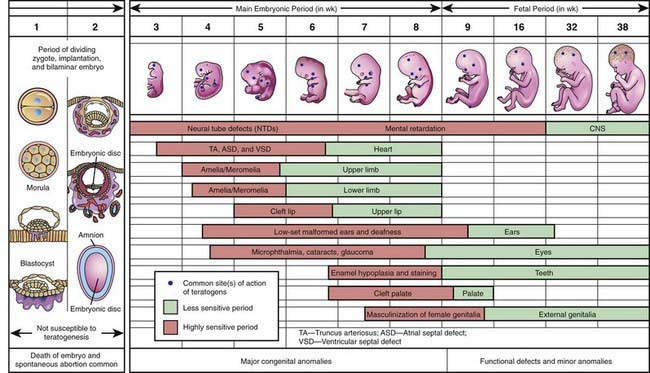

The association between an inadequate nutrient supply to the fetus with low birthweight has been recognized for decades; this adaptation on the part of the fetus will the inadequate supply presumably increases the likelihood that the fetus will survive until birth. Also recognized for decades is the fact that for any potential fetal insult, the extent and nature of its effects are determined by characteristics of the host as well as the dose and timing of the exposure. Inherited differences in the metabolism of ethanol may predispose certain individuals or groups to fetal alcohol syndrome. Organ systems are most vulnerable during periods of maximum growth and differentiation, generally during the 1st trimester (organogenesis). Figure 6-7 depicts sensitive periods during gestation for various organ systems. (See also http://www.criticalwindows.com/go_display.php for a more detailed listing of critical periods and specific developmental abnormalities.)

Figure 6-7 Critical periods in human prenatal development.

(From Moore KL, Persaud TVN: Before we are born: essentials of embryology and birth defects, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders/Elsevier.)

Fetal adaptations or responses to an adverse situation in utero (referred to as fetal programming or developmental plasticity) have lifelong implications for the individual. Fetal programming may prepare the fetus for an environment that matches that experienced in utero. Fetal programming in response to some environmental and nutritional signals in utero increase the risk of cardiovascular, metabolic, and behavioral diseases in later life. These adverse long-term effects appear to represent a mismatch between fetal and neonatal environmental conditions and the conditions that the individual will confront later in life; a fetus deprived of adequate calories may or may not as a child or teenager face famine. One proposed mechanism for fetal programming is epigenetic imprinting, in which two genes are inherited but one is turned off through epigenetic modification (Chapter 75). Imprinted genes play a critical role in fetal growth and thus may be responsible for the subsequent lifelong effects on growth and related disorders.

Teratogens associated with gross physical and mental abnormalities include various infectious agents (toxoplasmosis, rubella, syphilis); chemical agents (mercury, thalidomide, antiepileptic medications, and ethanol), high temperature, and radiation (Chapters 90 and 699).

Teratogenic effects may include not only gross physical malformation but also decreased growth and cognitive or behavioral deficits that only become apparent later in life. Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke is associated with lower birthweight, shorter length, and smaller head circumference, as well as decreased IQ and increased rates of learning disabilities. The effects of prenatal exposure to cocaine remain controversial and may be less dramatic than popularly believed. The effects include direct neurotoxic effects and effects mediated by reduced placental blood flow; associated risk factors include other prenatal exposures (alcohol and cigarettes used in large amounts by many cocaine-addicted women) as well as “toxic” postnatal environments frequently characterized by instability, multiple caregivers, and abuse and neglect (Chapter 36).

Psychologic distress during pregnancy can have serious consequences on the developing fetus through both maternal behaviors, including substance use, diminished appetite, or sleep disorder, and physiological changes involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Dysregulation of the HPA axis and ANS may explain the associations observed in some but not all studies between maternal distress and identified negative infant outcomes, including low birthweight, spontaneous abortion, prematurity, and decreased head circumference. Infants born to mothers experiencing high rates of depression or stress have been found to have delays in motor or mental development, or both, and in some studies higher levels of escape behaviors. Maternal anxiety between wk 12 and 22 but not wk 30 to 40 has been associated with increased rates of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Chapter 30), suggesting that there may be critical periods in fetal development especially sensitive to maternal stress. Although the mechanisms of the effect of maternal stress remain to be elucidated, the attributable load of emotional and behavioral problems in the infant due to antenatal stress, anxiety, or both is estimated to be about 15%.

Brazelton TB, Cramer BG. The earliest relationship. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1990.

Buitelaar JK, Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, et al. Prenatal stress and cognitive development and temperament in infants. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(Suppl 1):S5360.

Frank DA, Augustyn M, Knight WG, et al. Growth, development, and behavior in early childhood following prenatal cocaine exposure: a systematic review. JAMA. 2001;285:1613-1625.

Gicquel C, El-Osta A, Le Bouc Y. Epigenetic regulation and fetal programming. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22(1):1-16.

Krageloh-Mann I. Imaging of early brain injury and cortical plasticity. Exp Neurol. 2004;190(Suppl 1):S84-S90.

Lazinski MJ, Shea AK, Steiner M. Effects of maternal prenatal stress on offspring development: a commentary. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:363-375.

Moore KL, Persaud TVN. Before we are born: essentials of embryology and birth defects, ed 7. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2008.

Morokuma S, Doria V, Ierullo A, et al. Developmental change in fetal response to repeated low-intensity sound. Dev Sci. 2008;11:47-52.

Nesterenko TH, Aly H. Fetal and neonatal programming: evidence and clinical implications. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26:191-198.

Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V. Early stress, translational research and prevention science network: fetal and neonatal experience on child and adolescent mental health. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:245-261.