CHAPTER 50 Overuse Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Although many tissues are subject to fatigue injury, especially those of the immature skeleton,17 the concept of “overuse syndrome” has a broader definition. “No pain, no gain,” a cliché promoted in athletic circles for decades, expresses the underlying attitude that the advancement of one’s physical abilities may depend on exceeding the body’s limits far enough to cause pain and that less vigorous activity constitutes suboptimal performance. The pain that results from these activities may be transient, representing little more than a focal accumulation of muscle metabolic byproducts, or it may be longer lasting, indicating tissue injury. One dilemma is where to draw the line between the two extremes. Others are when it is safe to resume the activities that initially led to the noxious episode, whether or not adjustments in those activities are indicated, and at what point persistent pain no longer represents an acute injury state but signals a more ominous and less understood condition of chronic pain. These are only a few of the unknowns that are associated with overuse syndromes.

DEFINITIONS AND SYNONYMS

Usually thought to affect muscle or nerve, the overuse syndromes are imprecisely defined and go by a variety of names—repetitive strain injury, repetitive stress syndrome, chronic pain syndrome, cumulative trauma disorder, pain dysfunction syndrome (see Chapter 81), cervicobrachial occupational disorder, fibromyalgia, and a variety of activity-specific conditions such as writer’s cramp and tennis elbow, among others.6,12,16,18,33,40 The multiplicity of terms reflects the fact that the pathophysiologic mechanisms are, at best, poorly understood. It also contributes to confusion in classification, which, in turn, interferes with our learning from outcome studies. Overall, however, the term overuse syndrome is generally understood to reflect a painful condition, and all tissue types are at risk (Table 50-1). In this text, the term applies to a painful condition of the elbow region that results from excessive activity and whose symptoms have been present for an extended period of time.15

TABLE 50-1 Overuse-Induced Lesions at the Elbow and Affected Tissue Types

| Involved Tissue | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Bone | Angular change, hypertrophy |

| Joint | Degenerative arthrosis, loose body, spur, osteophyte (olecranon), osteochondritis dissecans |

| Synovium | Reactive synovitis, effusion |

| Ligament | Collateral ligament tear, stretch, calcification |

| Tendon | Epicondylitis, distal biceps, triceps detachment |

| Muscle | Myofasciitis, hypertrophy, compartment syndrome (anconeus) |

| Bursa | Inflammation, radiobicipital, olecranon |

| Nerve | Entrapment, cubital tunnel, arcade of Frohse |

Overuse syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion. No clear history of injury or date of onset is reported. Conditions that involve injury to specific structures, such as lateral epicondylitis and nerve entrapment syndromes (discussed in other chapters), must be ruled out before overuse conditions are considered. Chronicity also plays a role in the diagnosis of overuse syndrome. Pain of traceable onset less than 3 months before presentation for evaluation may be more likely to signify actual tissue injury related to a specific set of circumstances and to respond more favorably to conventional medical intervention. Conversely, pain of more than 6 months’ duration is much more likely (1) to have been affected by numerous nonorganic factors, (2) to present as a regional complaint, and (3) to display resistance to conventional medical intervention.6

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The overuse syndromes are most prominent in two groups of patients, performers and workers.5,7,8,11,15,20,27,36,39 Among the former are athletes and musicians, whose professions demand exceptional physical performance and arduous practice sessions. The tissues most often involved in athletes are the musculotendinous units, the ulnar nerve, and the collateral ligaments.38 In practice sessions, an activity is repeated to improve the performance level, often for extended periods. When the performers are called on to use the skills so perfected, an alteration in the performance level caused by pain may be noticeable and possibly may threaten their ability to continue. Any pre-existing injury can further increase the risk of developing an overuse condition.

Workers who daily are expected to perform certain job tasks are also at risk. Occupations reported to carry increased risk for overuse syndromes include typist, telephone operator, cash register operator, interpreter for the deaf, and packing plant worker.8,14,19,33 In the most common scenario, workers are stationed for long periods, during which they perform repetitive tasks. The actual number of workers who suffer from overuse syndrome is difficult to determine. Four percent of noninstitutionalized adults could recall at least 1 month of musculoskeletal pain and the nature of the impact of that pain.9 When specific jobs are evaluated, however, the incidence of upper extremity pain related to overuse may approach 30%.29

In both groups, psychosocial influences may play a major role in determining the pattern of functional recovery once a change in performance level is detected. Such factors actually may influence the manner in which the painful condition is presented to the treating physician, which, in turn, may alter the diagnosis and generate a self-perpetuating cycle of pain and reinforcement behaviors. It also must be understood that the worker’s condition is not static and that new stresses may enter into the situation over time. Often, the patience of both employee and employer evaporates and mutual mistrust develops. This may prompt the patient subconsciously to exaggerate reports of pain and limitation of function, further frustrating the care of the condition and often ending in confrontation and litigation.

ETIOLOGY

The causes of overuse syndrome have been the subject of speculation in many publications and studies.10,24,31,35,37 One of the earliest observations of pain in a worker subjected to “irregular motions and unnatural postures” dates to the early 18th century.37 Generally, overuse conditions are believed to arise from a combination of static and dynamic loads applied to postural muscles beyond the tolerable contraction level or duration.31 Isometric contraction greater than 10% of the maximum contraction level is not recommended35 because circulation in the contracting muscle may be compromised enough to cause tissue ischemia and accumulation of noxious metabolites.24 The noxious stimulus may prompt recruitment of other muscle groups, which, however, may be at a mechanical disadvantage for assuming such a role and may likewise, in the end, suffer muscle strain. The Japanese Association of Industrial Health identified several risk factors for the development of overuse syndrome, including dynamic muscle recruitment for repetitive tasks, static muscle recruitment for postural support, uncomfortable postures, mental stress, and ergonomic factors such as unpleasant working conditions (Fig. 50-1).2 Continued engagement in high-load activities other than occupational tasks, including hobbies, domestic chores, and recreational activities, may perpetuate the condition by reducing recovery time.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS

Historically, the involvement of psychological factors in the initiation and perpetuation of overuse syndrome has been recognized.23,26 For example, stress has been reported to be a pertinent risk in visual display operators.42 Stress, in this instance, may be related to high expectations on the part of the employee and the employer for accuracy and productivity in the face of monotonous tasks, equipment failure, static posture, and so on. Stress also may result from variables in physical surroundings such as lighting, noise, and coworker distractions. Athletes’ competitive bent may mean that stress plays a more prominent role in the development of overuse syndrome, and the unwillingness to rest the affected body part merely exacerbates the condition. Although it is important to identify the psychological and social factors that may contribute to overuse syndrome, it is equally important to avoid the common tendency to ascribe the entire problem to these factors.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

History taking is a most important and time-consuming component of the assessment. At first evaluation, several features commonly are evident. First, the degree of perceived impairment from the discomfort is significant, and the patient’s description of the discomfort may be dramatic and graphic.1,6 Some objective measure of pain may be useful, such as a pain thermometer to establish a baseline for future comparisons. Second, the patient typically has received many—and often conflicting—“other opinions” from family members, the popular press, coworkers, trainers, employers, and other physicians. Early in the first meeting, it is important tactfully to direct the patient’s attention away from previous opinions, to minimize learned behavior and bias and to maximize the effectiveness of future treatments. Finally, the patient may have learned to distort or exaggerate the severity and the area of involvement in an attempt to engage medical attention, this being a reaction to earlier incidents when the painful condition was trivialized by supervisors or industrial health care workers. It is critical, while establishing rapport, to assure the patient that all symptoms are important and that an accurate report of those symptoms greatly enhances the process.

During the physical examination, the key objective is to rule out all other possible causes of similar pain, including nerve entrapment syndromes, tendinitis, arthritis, bursitis, fracture, sprain, and other conditions such as tennis elbow. A systematic examination of the extremity, including musculoskeletal and neurologic function, circulation, and integument, is standard. After the more common processes have been ruled out, the diagnosis of overuse syndrome or of a similar condition begins to emerge.22,44 Generally, the patient has a relatively diffuse region of discomfort, and “trigger points” are not uncommon. One condition that may present as an unexplained overuse syndrome is fibromyalgia, which may demonstrate trigger points just distal to the medial or lateral epicondyle.18 Weakness may be a prominent complaint in overuse syndrome, but specific testing of muscles likely demonstrates neurologically intact neuromuscular pathways and “breakaway” weakness secondary to pain. It is critical to be mindful of the possible existence of the manifestations of pain dysfunction syndrome, because the treatment modalities are unique to that disorder, which generally does not respond to the therapies recommended for overuse syndrome.1,13 It may be useful to observe the athlete performing the activities that produce the discomfort in the field or the musician playing an instrument. An ergonomic evaluation of the worker’s environment, by either the physician or a qualified ergonomist, may be useful for understanding the circumstances surrounding the patient’s complaints. Finally, serial examination to determine the reproducibility of physical findings and to determine whether the nature of the condition “evolves” is extremely informative and useful.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

If there is concern that the patient may be describing signs and symptoms of an early inflammatory condition, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood count with differential, electrolyte assays, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody levels should be determined. The serum levels of the muscle enzymes creatine phosphokinase and aldolase have been reported to be elevated in some workers with upper extremity overuse syndrome, but it is believed that further investigation is necessary before widespread use of these determinations can be justified.5 Serologic testing for Lyme disease may be considered, especially if exposure risk factors are suggestive, because in the early clinical phases this disease can mimic overuse syndrome.4

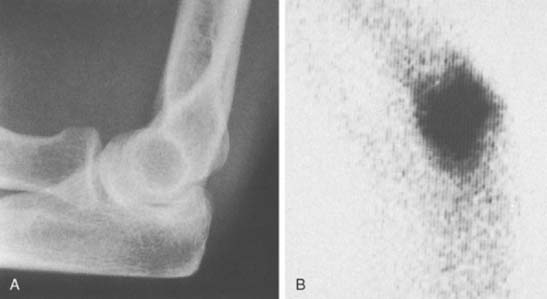

Standard radiographs of the elbow are necessary to evaluate the skeletal integrity of the humerus, the radius, and the ulna. It may be necessary to obtain special oblique views such as a radial head view or tomogram if a specific lesion is suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging is useful as a means of excluding obvious derangements or pathologic conditions. The usefulness of three-phase bone scintigraphy in the diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy has been largely accepted, and this study should be considered when evaluating for overuse syndrome.32 In fact, the technetium Tc 99 m bone scan is a useful screen for suspected inflammatory conditions with minimal findings (Fig. 50-2). Thermography, electromyography, quantitative sudomotor and autonomic reflex testing, and plethysmography all require substantially more investigation before they can be recommended for general use.33,36,45

TREATMENT

In the acute setting, standard techniques of pain management are appropriate—rest, thermal therapy (cold versus heat), ultrasound and phonophoresis, friction massage, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, and occasional injections of corticosteroid solutions into regions that are particularly tender and troublesome (see Chapter 9). Rest may be provided by temporary splint immobilization, but full-time immobilization causes stiffness and deconditioning that can quickly compound the original problem. Gentle, progressive, well-supervised physical therapy often enhances the rehabilitation process and maintains the strength and conditioning of body parts not affected by the overuse syndrome.41 The patient should continue to work when that is at all possible. To that end, the surgeon can define tolerable limits for tasks that will allow the patient to progress to recovery while maintaining a productive posture with the employer. Keeping the patient away from the workplace can affect the patient’s perception of the degree of impairment that the condition may be generating and could constitute negative reinforcement for recovery (see Chapter 44). On the other hand, some conditions are markedly correlated with occupation, and changing jobs may be an important treatment measure (see Fig. 50-1).

Treatment of chronic pain, regardless of the cause, is a difficult process that requires a multidisciplinary approach. Generally speaking, the conventional therapeutic approach described earlier is ineffective and in certain circumstances may be counterproductive. Attempts to treat the symptoms with splints, medications, or injections should cease. It must be made clear that the condition will not respond to medical or surgical intervention. This is not to say that it will not improve with some types of therapy; it merely underscores the need for the patient to stop searching for a medical answer to the problem. A survey of 116 therapists revealed that many common educational themes are employed, especially the nature of the disease process, normal and abnormal anatomy, and job modification.25

The patient should have a functional capacity evaluation, which is useful for determining impairment levels and constructing a work-hardening program.41 Referral to a pain management clinic may avail the patient of unconventional modalities such as TENS and biofeedback. Stellate ganglion block, contrast baths, and massage may benefit patients who are believed to have autonomic dysfunction. If the patient has retained legal counsel or is pursuing workmen’s compensation independently, the treating physician becomes an important source of information and will be asked to determine if the workplace was responsible for, or substantially contributed to, the onset of symptoms; what level of impairment due to the symptoms has been established; and what if any permanent restrictions will be necessary as a result of these findings. An independent impair-ment evaluation center can be very helpful in these circumstances.

Prevention at the workplace and preconditioning of workers are critical to combating the overuse syndrome epidemic. Reasonable employers are evaluating workplaces with ergonomists to determine what modifications in the workplace and in task rotations will reduce the incidence of overuse syndromes.3,30,43 Additionally, implementation of ergonomic exercise programs, better employee education and orientation, and soliciting employees’ feedback seem to have salutary effects on reducing overuse syndrome.30 There still remains controversy, however, about whether proof exists that ergonomic adjustments and compensations are efficacious.46

SUMMARY

Overuse syndrome of the upper extremity is a poorly understood condition that, by some measures, is reaching nearly epidemic proportions. Clear guidelines for classification, diagnosis, and treatment are needed. Until they are established, the physician carries the responsibility of educating patients, employers, and the community at large and the burden of studying the process to educate fellow physicians.21

1 Amadio P.C. Pain dysfunction syndromes: current concept reviews. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:944.

2 Aoyama H., Ohara H., Oze Y., Itani T. Recent trends in research on occupational cervicobrachial disorder. J. Hum. Ergol. (Tokyo). 1979;8:39.

3 Armstrong T.J. Ergonomics and cumulative trauma disorders. Hand Clin. 1986;2:553.

4 Arthritis Foundation. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, 9th ed., Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 1988:188.

5 Bjelle A., Hagberg M., Michaelsson G. Clinical and ergonomic factors in prolonged shoulder pain among industrial workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 1979;5(suppl.):205.

6 Blair W.F. Cumulative trauma disorder in the upper extremity. Iowa Orthopedics J. 1990;11:103.

7 Brooks P.M. Occupational pain syndromes. Med. J. Austral. 1986;144:170.

8 Cohn L., Lowry R.M., Hart S. Overuse syndromes of the upper extremity in interpreters for the deaf. Orthopedics. 1990;13:207.

9 Cunningham L.S., Kelsey J.L. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am. J. Public Health. 1984;74:574.

10 Dennett X. Overuse syndrome: a muscle biopsy study. Lancet. 1988;23:905.

11 Dimberg L., Olafsson A., Stefansson E., Aagaard H., Oden A., Anderson G.B., Hansson T., Hagert C.G. The correlation between work environment and the occurrence of cervicobrachial symptoms. J. Occup. Med. 1989;31:447.

12 Dobyns J.H. Cumulative trauma disorder of the upper limb. Hand Clin. 1991;7:587.

13 Dobyns J.H. Pain dysfunction syndrome. In: Gelberman R.H., editor. Operative Nerve Repair and Reconstruction. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co.; 1991:1489.

14 Ferguson D. The “new” industrial epidemic. Med. J. Austral. 1984;142:318.

15 Fry H.J.H. Overuse syndrome of the upper limb in musicians. Med. J. Austral. 1986;144:182.

16 Fry H.J.H. Overuse syndrome, alias tenosynovitis/tendinitis: the terminology hoax. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1986;78:414.

17 Gill T.J.4th, Micheli L.J. The immature athlete. Common injuries and overuse syndromes of the elbow and wrist. Clin. Sports Med. 1996;15:401-423.

18 Goldenberg D.L. Fibromyalgia syndrome (fibrositis). Mediguide Inflam. Dis. 1988;7:1.

19 Hadler N.M. Work-related disorders of the upper extremity. Part I: Cumulative trauma disorders-a critical review. Occup. Prob. Med. Prac. 1989;4:1.

20 Hadler N.M. Industrial rheumatology: the Australian and New Zealand experiences with arm pain and backache in the work-place. Med. J. Austral. 1986;144:191.

21 Hadler N.M. Cumulative trauma disorders: an iatrogenic concept. J. Occup. Med. 1990;32:38.

22 Howard N.J. Peritendinitis crepitans. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1937;19:447.

23 Ireland D.C.R. Psychological and physical aspects of occupational arm pain. J. Hand Surg. 1988;13B:5.

24 Karlsson J., Ollander B. Muscle metabolites with exhaustive static exercises of different durations. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1972;86:309.

25 Lawler A.L., James A.B., Tomlin G. Educational techniques used in occupational therapy treatment of cumulative trauma disorders of the elbow, wrist and hand. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1997;51:113-118.

26 Linton S.J., Kamwendo K. Risk factors in the psychosocial work environment for neck and shoulder pain in secretaries. J. Occup. Med. 1989;31:609.

27 Louis D.S. Cumulative trauma disorders. J. Hand Surg. 1987;5:823.

28 Louis D.S. Evolving concerns relating to occupational disorders of the upper extremity. Clin. Orthop. 1990;254:140.

29 Luopajarvi T., Kuorinka I., Virolainen M., Holmberg M. Prevalence of tenosynovitis and other injuries of the upper extremities in repetitive work. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 1979;5(Suppl.):48.

30 Lutz G., Hansford T. Cumulative trauma disorder controls: the ergonomic program at Ethicon, Inc. J. Hand Surg. 1987;12A:863.

31 Maeda K., Hunting W., Grandjean E. Factor analysis of localized fatigue complaints of accounting machine operators. J. Hum. Ergol. (Tokyo). 1982;11:37.

32 Mackinnon S.E., Holder L.E. The use of three-phase radionuclide bone scanning in the diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. J. Hand Surg. 1984;9:556.

33 McDermott F.T. Repetition strain injury: a review of current understanding. Med. J. Austral. 1986;144:196.

34 McPhee B., Worth D.R. Neck and upper extremity pain in the work-place. In: Grant R., editor. Physical Therapy of the Cervical and Thoracic Spine. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988:291.

35 Onishi N., Sakai K., Kogi K. Arm and shoulder muscle load in various keyboard operating jobs of women. J. Hum. Ergol. (Tokyo). 1982;11:89.

36 Pochachevskyl R. Thermography in post-traumatic pain. Am. J. Sports Med. 1987;15:243.

37 Ramazinni B.. Wright W., editor. The Diseases of Workers. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1940;1717. (trans.)

38 Rettig A.C. Elbow, forearm and wrist injuries in the athlete. Sports Med. 1998;25:115.

39 Ryan G.A., Hampton M. Comparison of data process operators with and without upper limb symptoms. Comm. Health Stud. 1988;12:63.

40 Semple J.C. Tenosynovitis, repetitive strain injury, cumulative trauma disorder, and overuse syndrome, et cetera (Editorial). J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:536.

41 Schultz-Johnson K. Work hardening: a mandate for hand therapy. Hand Clin. 1991;7:597.

42 Smith M.J., Cohen B.G., Stammerjohn L.W. An investigation of health complaints and job stress in visual display operations. Hum. Factors. 1981;23:387.

43 Stock S.R. Work-place ergonomic factors and the development of musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and upper limbs: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Indust. Med. 1991;19:87.

44 Thompson A.R., Plewes L.W., Shaw E.G. Peritendinitis crepitans and simple tenosynovitis: a clinical study of 544 cases in industry. Br. J. Industr. Med. 1951;8:150.

45 Uematsu S., Hendler N., Hungerford D., Long D., Ono N. Thermography and electromyography in the differential diagnosis of chronic pain syndromes and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1981;21:165.

46 Verhagen A.P., Kerels C., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M., Feleus A., Dahaghin S., Burdorf A., De Vet H.C., Koes B.W. Ergonomic and physiotherapeutic interventions for treating work-related complaints in the arm, neck or shoulder in adults. A Cochrane systematic review. Eura. Medicophys. 2007;43:391.