157 Over-the-Counter Medications

• Acetaminophen poisoning should be considered in patients presenting with over-the-counter medication misuse or overdose.

• Poisonings with antihistamine medications may manifest with antimuscarinic toxicity and sedation, but cardiac toxicity and seizures are also possible.

• Treatment for antihistamine poisoning is supportive care, but sodium bicarbonate and physostigmine may be helpful adjuncts.

• Dextromethorphan poisoning manifests as sedation, movement disturbances, and psychoactive dysphoria. Most of these effects are mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate, rather than by opioid receptor activity.

• In overdose, poisoning with oral amphetamine-like decongestants may manifest as a sympathomimetic toxidrome.

• Imidazoline ocular and nasal decongestants such as oxymetazoline (Afrin) tetrahydrozoline (Visine), and naphazoline (Naphcon) may cause significant sedation when they are ingested orally.

• Diphenoxylate (Lomotil) can cause recurrent and delayed respiratory depression.

• Dietary supplements are mostly safe but are unregulated. Common conditions leading to poisoning include mislabeling, variations in concentration, contamination with unintended agents, and intentional adulteration.

• Vitamin A toxicity may cause increased intracranial pressure with associated symptoms.

Antihistamines

Epidemiology

Antihistamines are among the most frequently used medications in the United States.1 Most of these drugs are available without a prescription. Although their efficacy is questionable, antihistamines are widely used for the symptomatic relief of cold and allergy symptoms. They are also found in nonprescription sleeping aids. Because of widespread access, these agents are commonly ingested intentionally, in suicide attempts, and unintentionally, particularly by children. Approximately 90,000 cases of antihistamine ingestions are reported to poison centers in the United States every year, and almost half of those involve children younger than 6 years.2

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

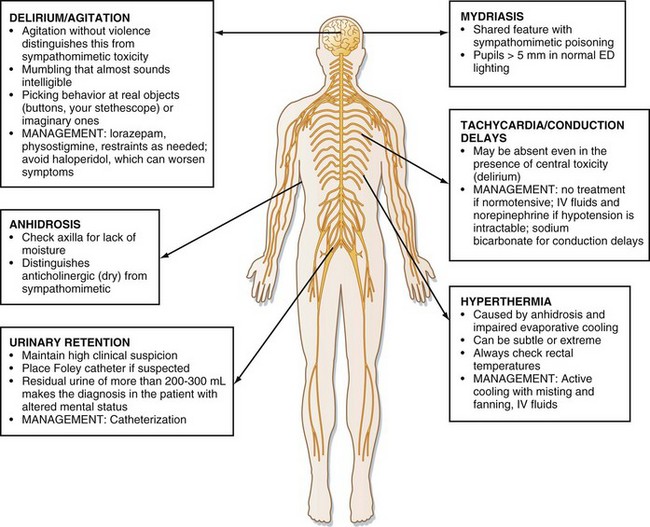

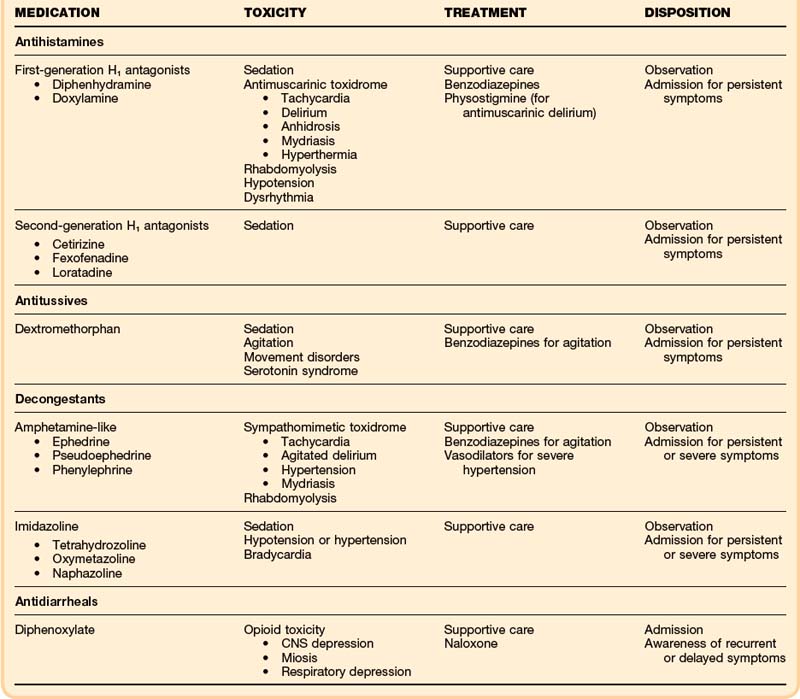

Although sedation is common with larger ingestions, signs of antimuscarinic toxicity may also be present (Box 157.1). In addition, patients may have mild hypotension or more worrisome wide complex dysrhythmia resulting from sodium channel–blocking effects of some antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine). Cardiovascular toxicity associated with some antihistamines is indistinguishable from that associated with cyclic antidepressants (Fig. 157.1).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of antihistamine toxicity is broad because many medications, street drugs, and disease processes can cause a presentation characterized by sedation or delirium, or both (Box 157.2). The emergency physician must consider nontoxicologic causes of altered mental status, such as infection and traumatic brain injury, and evaluate for these nontoxicologic conditions accordingly if the presence of the conditions cannot be excluded by other means. Computed tomography of the head and lumbar puncture may be warranted. In particular, patients presenting with antimuscarinic toxicity may be delirious, hyperthermic, and tachycardic, features that mimic infectious causes.

Treatment

Hospital treatment should also be focused on supportive care with assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation. Particular attention should be paid to controlling agitation and hydration (Table 157.1). Agitation should be treated with benzodiazepines in doses titrated to desired effect (e.g., lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg by intravenous [IV] push to effect). In addition to chemical restraint, physical restraint for patient and staff safety may be needed. Hydration should be addressed with 1- to 2-L boluses of 0.9% saline solution to ensure adequate urine output.

In patients who present within 1 hour of drug ingestion and who are alert and cooperative, activated charcoal (50 g or 1g/kg up to 50 g in children) should be considered. Data in humans are insufficient to support the use of activated charcoal beyond 1 hour.3

Physostigmine is a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that crosses the blood-brain barrier; it increases synaptic acetylcholine and may temporarily reverse antimuscarinic delirium. Peripheral signs may also be reversed. It may also be used therapeutically to control agitation.4 Physostigmine may have more value as a diagnostic tool by precluding the need for invasive tests (e.g., lumbar puncture) if complete reversal of delirium is achieved following administration.5 Beyond diagnostic use, the role of physostigmine in the treatment of most antimuscarinic poisonings with minor symptoms is debatable, and caution should be used if a possibility of tricyclic antidepressant ingestion exists.

Antitussives: Dextromethorphan

Epidemiology

Dextromethorphan was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an over-the-counter antitussive in 1958. It is a common component of cold preparations, and its nonmedical use (abuse) appears to be increasing, especially among adolescents.6 Abuse of Coricidin (known on the streets as “Skittles”) and Robitussin (known as “DXM” and “robo”) has highlighted dextromethorphan’s abusive potential.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Along with altered mental status, dextromethorphan may cause gait disturbances known as “robo-walking.”7 Serotonin syndrome, which consists of a triad of central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, neuromuscular dysfunction (clonus, hyperreflexia), and autonomic instability (tachycardia, mild hyperthermia), may also be noted in patients with toxicity.8

Treatment

Hospital treatment should be focused on supportive care with assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation. Attention should be paid to controlling agitation and hydration. Agitation should be treated with benzodiazepines in doses titrated to effect (IV lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg titrated to effect) (see Table 157.1). Reducing environmental stimuli may also be helpful. In addition to chemical restraint, physical restraint for patient and staff safety may be needed. Hydration should be addressed with 1- to 2-L boluses of 0.9% saline solution to ensure adequate urine output. Decontamination with activated charcoal may be considered in an alert, cooperative patient who presents within an hour of a possible ingestion. Supportive care is the treatment of choice. IV naloxone (1 to 2 mg) may be given for significant sedation, although reversal may not occur.9

Decongestants: Pseudoephedrine, Ephedrine, Phenylephrine, Oxymetazoline, and Tetrahydrozoline

Epidemiology

Over-the-counter decongestants rank among the top five most commonly used medications.1 They are frequently present in multiple ingredient cough and cold products. Some are abused for their stimulatory effects or diverted for the production of methamphetamines. As with other over-the-counter medications, children are frequent victims of unintentional poisonings or dosing errors, and decongestant exposure in this population has been linked to adverse outcomes.2

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The presenting signs and symptoms from the ingestion of over-the-counter decongestants will vary depending on the class ingested (see Table 157.1). Ingestion of an amphetamine-like decongestant typically presents signs and symptoms of sympathomimetic toxicity due to the increased stimulation of both α- and β-adrenergic receptors. This is typified by agitation, delirium, tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and mydriasis. Ingestion of imidazolines, which are meant for topical use, usually presents with sedation, bradycardia and hypertension early with subsequent hypotension. Respiratory depression, sedation, and miosis, mimicking opioid toxicity, have been described.10

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

If the history of ingestion is not clear then the differential diagnosis for decongestant ingestions can be broad, especially considering the disparate presentations of the amphetamine-like and the imidazoline classes (see Table 157.1). Coingestions and nontoxicologic processes must be considered. Rhabdomyolysis and cardiac ischemia should be evaluated for in patients with significant toxicity.

Treatment

Standard prehospital care should be sufficient for decongestant-toxic patients, with particular attention paid to controlling agitation. Decontamination with activated charcoal is suitable for the alert patient with exposure in the previous hour. Agitation, tachycardia, and hypertension should be aggressively treated with benzodiazepines (IV lorazepam, 1 to 2 mg, or IV diazepam, 5 to 10 mg, titrated to effect). The physician must aggressively hydrate these patients to treat rhabdomyolysis. For refractory hypertension, an α-adrenergic antagonist (IV phentolamine, 5 mg) or a venous and arteriolar vasodilator (IV nitroprusside, 0.3 to 10 mcg/kg/min) should be given. In severe cases of CNS depression after imidazoline-type decongestant overdose, IV naloxone may be given (2 to 4 mg) but its effects are inconsistent, and endotracheal intubation may rarely be needed to support ventilation.11

Antidiarrheals: Loperamide and Diphenoxylate

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Loperamide is generally well tolerated even in large ingestions, and drowsiness is the most common effect.12 Diphenoxylate is significantly more toxic, and overdoses commonly manifest with some degree of opioid toxicity (e.g., CNS depression, respiratory depression, miosis, decreased bowel motility), with or without the antimuscarinic effects of the atropine (see Table 157.1).

Treatment and Disposition

In general, loperamide has a high safety profile and has been associated with very few adverse events, even in overdose. However, diphenoxylate overdoses can cause significant symptoms, usually related to respiratory depression (see Table 157.1). Respiratory depression by can be recurrent or delayed, sometimes up to 24 hours after the ingestion, and children are particularly at risk.13 Decontamination with activated charcoal in the cooperative patient may be useful even beyond the 1 hour, given the impairment of gastrointestinal motility with these agents. IV naloxone (0.4 to 2.0 mg) is effective in reversing the respiratory depression and other signs of opioid toxicity, but CNS and respiratory depression may recur, and an IV naloxone infusion may be needed.13

Dietary Supplements

Epidemiology

Any ingredient taken for the purpose of promoting health is considered a dietary supplement. Innumerable examples of dietary supplements exist, and a national surveyed showed that more than 15% of the U.S. population had used one or more in the previous week.14 Ginkgo, St. John’s wort, ginseng, echinacea, and synephrine are among the more commonly used dietary supplements (Table 157.2). Unlike with prescription drugs, proof of safety and proof of efficacy are not required for dietary supplements as long as the maker does not claim that the agent is a treatment for a particular disease. To be removed from the market, a dietary supplement must be proven unsafe. This situation occurred in 2006, when the FDA banned of ephedra over cardiovascular concerns.15

| DIETARY SUPPLEMENT | SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF TOXICITY |

|---|---|

| Synephrine (bitter orange) |

GI, gastrointestinal; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Depending on the specific dietary supplement, presenting signs and symptoms vary. Table 157-2 lists some of the possible toxic manifestations of the more common dietary supplements.

Vitamins

Epidemiology

Vitamins are frequently taken in supratherapeutic amounts. This is done typically under the premise of “more is better” or purportedly to treat or prevent conditions ranging from viral upper respiratory tract infections to Alzheimer dementia. Parents’ concern about their children’s eating patterns may result in vitamin oversupplementation.16 All these factors, added to the ready availability of vitamins, make vitamins prime targets for potential toxic exposures.17

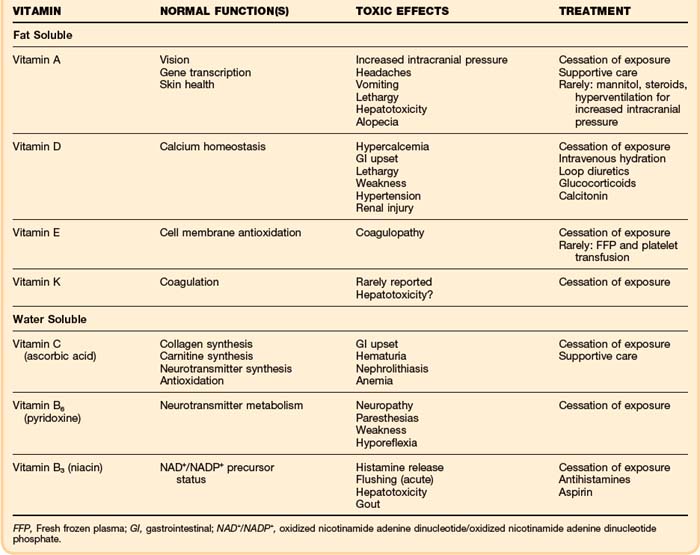

Pathophysiology

Vitamins can be grouped into two main categories: water soluble and fat soluble. Toxicity may be caused by either group, though in general toxicity from water-soluble vitamins are rarer and less severe as they do not accumulate as fat-soluble vitamins do. Vitamin A and D, which are both fat soluble, have well described toxicity. Table 157.3 describes the normal function of the most common vitamins and their toxic effects.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The presenting signs and symptoms of hypervitaminosis depend on the offending vitamin.16–19 Table 157.3 lists the toxic effects of the most clinically relevant vitamins.

Treatment

Typically, supportive care and cessation of the offending vitamin are sufficient to treat most vitamin toxicities. In the case of vitamin A toxicity, measures to reduce intracranial pressure may be warranted, and in the case of vitamin D toxicity, standard treatment for hypercalcemia (IV hydration and loop diuretics) should be employed (see Table 157.3).

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Tips and Tricks

• Many vitamin preparations contain iron or fluoride, so it is imperative that these agents be considered and evaluated as possible coingestants.

• In patients with mixed ingestion, older patients, or very young patients, physical findings may be variable and the clinical picture unclear.

• Peripheral findings do not always accompany central findings in antihistamine overdose; therefore, a confused patient may not always have tachycardia or anhidrosis.

• In all cases of potential poisoning, nontoxicologic causes of altered mental status should also be considered.

• With dextromethorphan ingestions, genetic differences in speed of metabolism of the drug to dextrorphan can result in either predominance of sedation or dysphoria.

Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Manoguerra AS, et al. Dextromethorphan poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. American Association of Poison Control Centers. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45:662–677.

Daggy A, Kaplan R, Roberge R, Akhtar J. Pediatric Visine (tetrahydrozoline) ingestion: case report and review of imidazoline toxicity. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2003;45:210–212.

Haller C, Benowitz NL. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1833–1838.

Tovar RT, Petzel RM. Herbal toxicity. Dis Mon. 2009;55:592–641.

1 Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, et al. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002;287:337–344.

2 Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr., et al. 2009 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 27th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48:979–1178.

3 Chyka PA, Seger D, Krenzelok EP, Vale JA. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists: position paper. Single-dose activated charcoal. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:61–87.

4 Burns MJ, Linden CH, Graudins A, et al. A comparison of physostigmine and benzodiazepines for the treatment of anticholinergic poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:374–381.

5 Schneir AB, Offerman SR, Ly BT, et al. Complications of diagnostic physostigmine administration to emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:14–19.

6 Bryner JK, Wang UK, Hui JW, et al. Dextromethorphan abuse in adolescence: an increasing trend: 1999–2004. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1217–1222.

7 Warden CR, Diekema DS, Robertson WO. Dystonic reaction associated with dextromethorphan ingestion in a toddler. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:214–215.

8 Schwartz AR, Pizon AF, Brooks DE. Dextromethorphan-induced serotonin syndrome. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46:771–773.

9 Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Manoguerra AS, et al. Dextromethorphan poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. American Association of Poison Control Centers. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45:662–677.

10 Daggy A, Kaplan R, Roberge R, Akhtar J. Pediatric Visine (tetrahydrozoline) ingestion: case report and review of imidazoline toxicity. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2003;45:210–212.

11 Wiley JF, 2nd., Wiley CC, Torrey SB, Henretig FM. Clonidine poisoning in young children. J Pediatr. 1990;116:654–658.

12 Litovitz T, Clancy C, Korberly B, et al. Surveillance of loperamide ingestions: an analysis of 216 poison center reports. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:11–19.

13 McCarron MM, Challoner KR, Thompson GA. Diphenoxylate-atropine (Lomotil) overdose in children: an update (report of eight cases and review of the literature). Pediatrics. 1991;87:694–700.

14 Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Kelley K, et al. Recent trends in use of herbal and other natural products. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:281–286.

15 Haller C, Benowitz NL. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1833–1838.

16 Herbert V. The vitamin craze. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:173–176.

17 Bendich A. Safety issues regarding the use of vitamin supplements. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;669:300–310. discussion 311–12

18 Omaye ST. Safety of megavitamin therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1984;177:169–203.

19 Alhadeff L, Gualtieri CT, Lipton M. On the toxicity of water-soluble vitamins. Nutr Rev. 1984;42:265–267.