31 Otitis

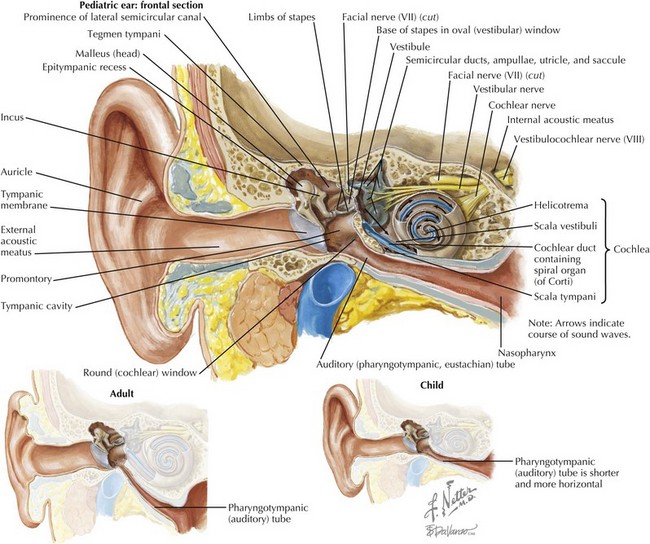

To first review basic anatomy, the ear is divided into three parts: the outer, middle, and inner ear. The outer ear consists of the auricle and ear canal up to the tympanic membrane (TM). The middle ear is bounded by the TM and the round window. The middle ear contains three bones that conduct sound—the malleus, the incus, and the stapes—and the Eustachian (pharyngotympanic) tube that connects the middle ear cavity to the pharynx. The inner ear contains the cochlea and semicircular canals (Figure 31-1).

Otitis Externa

Clinical Presentation

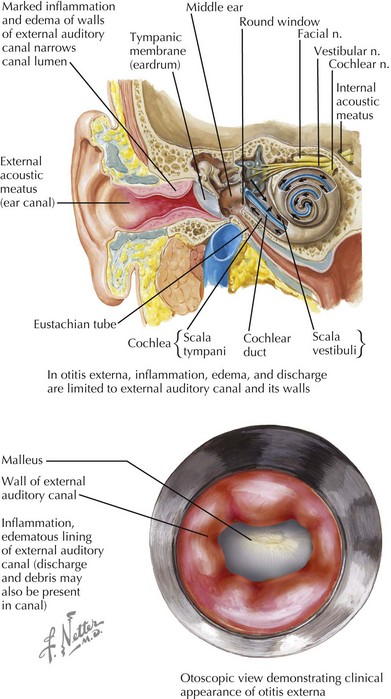

In AOE, the physical examination is critical in diagnosis. Debris and cerumen must be cleared from the canal to ensure accurate otoscopy of the TM as well as to improve the ability of topical treatment to reach the area of infection. The hallmark sign of AOE is tenderness of the tragus or the pinna when manipulated. The clinician will see diffuse edema and erythema of the canal, possibly with otorrhea or other debris present (Figure 31-2). The TM may be erythematous, but this should not imply a definite diagnosis of otitis media. On pneumatic otoscopy, if there is normal movement of the TM without visible effusion, the erythema may be attributed to the AOE.

Otitis Media

Clinical Presentation

Acute Otitis Media

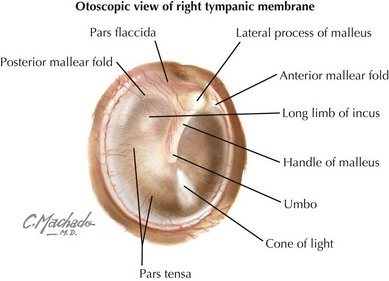

AOM is common in children of all ages. Parents will generally bring their child to the office with a complaint of pain, pulling on the ear, fever, and/or ear drainage. Before examining a child for AOM or OME, the physician must be comfortable with otoscopy of the normal ear and TM. The most common TM landmarks visible on a normal examination include the umbo and handle of the malleus, the shadow of the incus, and the cone of light reflex (Figure 31-3). On pneumatic otoscopy, the physician should appreciate the back-and-forth motion of the normal TM with gentle squeezing and releasing of the bulb.

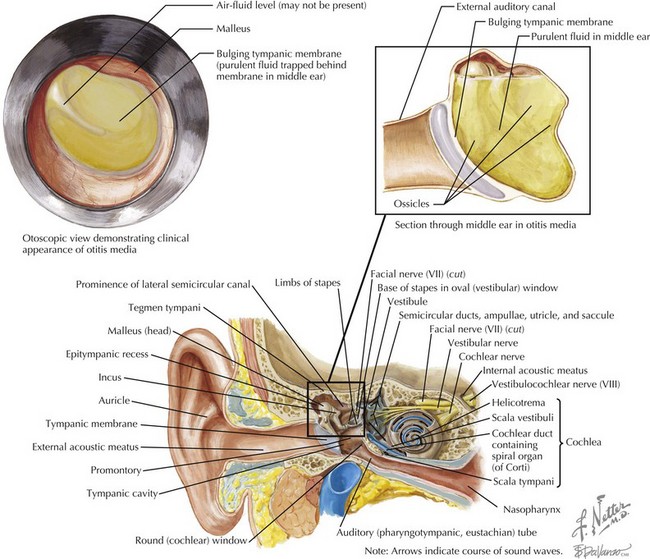

A physical examination is required to determine the presence of a middle ear effusion (MEE). On inspection of the TM, it may be bulging, or an air-fluid level or bubble will be visible. The normal landmarks may be obscured and the light-reflex absent or distorted. The movement of the TM will be decreased or absent. Sometimes purulent material will be seen behind the TM (Figure 31-4). In the case of a perforated TM, the perforation itself may be visible or the canal may be filled with debris, fluid, or exudate. Erythema of the TM alone is nondiagnostic because the TM may be red in many other conditions, including AOE and OME and during a child’s crying. In children, lack of cooperation often impedes a complete examination. Treatment recommendations for a nondiagnostic, uncertain examination are discussed further below.

Evaluation and Management

Acute Otitis Media Treatment

In recent years, there has been a shift in the treatment recommendations for AOM from universal antibiotic use to include the option of observation before requiring antibiotics. Clinical research has shown that most children older than 2 years of age have spontaneous resolution of AOM without antibiotic therapy. There also appears to be no increased risk for complications such as mastoiditis with watchful waiting of older children. Importantly, the observation option helps to limit further emergence of resistant bacteria. The decision to observe or treat should be based on the child’s age, diagnostic certainty, and disease severity (Table 31-1). The treatment guidelines proposed by the New York Regional Otitis Project, the AAP, and the American Academy of Family Physicians recommend treatment differences based on age because severe complications are most common in infants and the youngest children.

Table 31-1 Criteria for Initial Antibiotic Treatment versus Observation in Children with Acute Otitis Media

| Age | Certain Diagnosis | Uncertain Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| <6 months | Antibiotic therapy | Antibiotic therapy |

| 6 months–2 years | Antibiotic therapy | Antibiotic if severe; observation option if not* |

| >2 years | Antibiotic if severe; observation option if not* | Observation option* |

* Observation option is appropriate only when follow-up can be ensured within 48 to 72 hours and antibiotics started if symptoms persist or worsen. Nonsevere illness is defined as only mild otalgia and fever below 39°C. A history of acute symptom onset, middle ear effusion, and signs of middle ear inflammation make a certain diagnosis.

Modified Rosenfeld R: Observation option toolkit for acute otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 58(1):1-8, 2001; New York Regional Otitis Project: Observation Option Toolkit for Acute Otitis Media. State of New York, Department of Health, Publication #4894, March 2002; and American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 113(5):1451-1465, 2004.

Osguthorpe JD, Nielsen DR. Otitis externa: review and clinical update. Am Fam Phys. 2006;74(9):1510-1516.

Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(7 Pt 1):1166-1177.

Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(Suppl 4):S4-S23.

Rosenfeld RM, Singer M, Wasserman JM, Stinnett SS. Systematic review of topical antimicrobial therapy for acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(Suppl 4):S24-S48.

American Family Physicians; American Academy of Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1412-1429.

American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1451-1465.

Griffin GH, Flynn C, Bailey RE, Schultz JK: Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD003423, 2006.

Lous J, Burton MJ, Felding JU, et al: Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001801, 2005.

New York Regional Otitis Project. Observation Option Toolkit for Acute Otitis Media. State of New York: Department of Health; March 2002. Publication #4894

Paradise JL, Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, et al. Developmental outcomes after early or delayed insertion of tympanostomy tubes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(6):576-586.

Paradise JL, Feldman HM, Campbell TF, et al. Tympanostomy tubes and developmental outcomes at 9 to 11 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(3):248-261.

Rosenfeld R. Observation option toolkit for acute otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;58(1):1-8.