Chapter 289 Other Tissue Nematodes

Loiasis (LOA LOA)

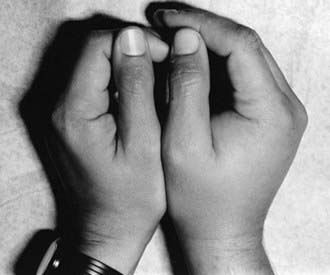

Loiasis is caused by infection with the tissue nematode Loa loa. The parasite is transmitted to humans via diurnally biting flies (Chrysops) that live in the rain forests of West and Central Africa. Migration of adult worms through skin, subcutaneous tissue, and subconjunctival area can lead to transient episodes of pruritus, erythema, localized edema known as Calabar swellings, which are nonerythematous areas of subcutaneous edema 10-20 cm in diameter typically found around joints such as the wrist or the knee (Fig. 289-1), or eye pain. They resolve over several days to weeks and may recur at the same or different sites. Although lifelong residents of endemic regions may have microfilaremia and eosinophilia, these individuals are often asymptomatic. In contrast, travelers to endemic regions may have a hyperreactive response to L. loa infection characterized by frequent recurrences of swelling, high-level eosinophilia, debilitation, and serious complications such as glomerulonephritis and encephalitis. Diagnosis is usually established on clinical grounds, often assisted by the infected individual reporting a worm being seen crossing the conjunctivae. Microfilariae may be detected in blood smears collected between 10 AM and 2 PM. Adult worms should be surgically excised when possible. Diethylcarbamazine is the agent of choice for eradication of microfilaremia, but the drug does not kill adult worms. Because treatment-associated complications such as pruritus, fever, generalized body pain, hypertension, and even death may occur, especially with high microfilarial levels, the dose of diethylcarbamazine should be increased gradually (children, 1 mg/kg PO on day 1, 1 mg/kg tid PO on day 2, 1-2 mg/kg tid PO on day 3, 6 mg/kg/day divided tid PO on days 4-21; adults, 50 mg PO on day 1, 50 mg tid PO on day 2, 100 mg tid PO on day 3, 6 mg/kg/day divided tid PO on days 4-21). Full doses can be instituted on day 1 in persons without microfilaremia. Individuals concurrently infected with O. volvulus are at increased risk for developing encephalopathy with ivermectin treatment. A single dose of ivermectin (150 µg/kg) decreases microfilarial densities in the blood in persons with high-density microfilaremia. A 3 wk course of albendazole can also be used to slowly reduce microfilarial levels as a result of embryotoxic effects on the adult worms. Antihistamines or corticosteroids may be used to limit allergic reactions secondary to killing of microfilariae. Personal protective measures include avoiding areas where biting flies are present, wearing protective clothing, and using insect repellents. Diethylcarbamazine (300 mg PO once weekly) prevents infection in travelers who spend prolonged periods of time in endemic areas. L. loa do not harbor Wolbachia endosymbionts, and therefore doxycycline has no effect on infection.

Onchocerciasis (Onchocerca volvulus)

Burnham G. Onchocerciasis. Lancet. 1998;351:1341-1346.

Molyneux DH, Bradley M, Hoerauf A, et al. Mass drug treatment for lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:516-522.

Remme JH. Research for control: The onchocerciasis experience. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:243-254.

Udall DN. Recent updates on onchocerciasis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:53-60.

Boussinesq M. Loaiasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:715-731.

Padgett JJ, Jacobsen KH. Loiasis: African eye worm. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:983-989.

Pion DS, Gardon J, Kamgno J, et al. Structure of the microfilarial reservoir of Loa loa in the human host and its implications for monitoring the programmes of Community-Directed Treatment with Ivermectin carried out in Africa. Parasitology. 2004;129:613-626.

Infection with Animal Filariae

Litwin CM. Pet-transmitted infections: diagnosis by microbiologic and immunologic methods. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:768-777.

Orihel TC, Eberhard ML. Zoonotic filariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:366-377.

Pampiglione S, Rivasi F, Angeli G, et al. Dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria repens in Italy, an emergent zoonosis: report of 60 new cases. Histopathology. 2001;38:344-354.

Chotmongkol V, Sawanyawisuth K, Thavornpitak Y. Corticosteroid treatment of eosinophilic meningitis. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1295-1303.

Lo Re V3rd, Gluckman SJ. Eosinophilic meningitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:217-223.

Sawanyawisuth K. Treatment of angiostrongyliasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:990-996.

Wang QP, Lai DH, Zhu XQ, et al. Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:621-630.

Hulbert TV, Larsen RA, Chandrasoma PT. Abdominal angiostrongyliasis mimicking acute appendicitis and Meckel’s diverticulum: report of a case in the United States and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:836-840.

Kramer MH, Greer GJ, Quinonez JF, et al. First reported outbreak of abdominal angiostrongyliasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:365-372.

Loria-Cortes R, Lobo-Sanahuja JF. Clinical abdominal angiostrongyliasis. A study of 116 children with intestinal granulomas caused by Angiostrongylus costaricensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:538-544.

Dracunculiasis (Dracunculus medinensis)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: progress toward global eradication of dracunculiasis, January 2007-June 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1173-1175.

Greenaway C. Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease). CMAJ. 2004;170:495-500.

Sing A, Wienert P, Sabisch P, et al. Photo quiz. Infection due to Dracunculus medinensis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1361. 1508–1509

Lo Re V3rd, Gluckman SJ. Eosinophilic meningitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:217-223.

Ramirez-Avila L, Slome S, Schuster FL, et al. Eosinophilic meningitis due to Angiostrongylus and Gnathostoma species. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:322-327.

Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.