Other Protozoa

1. Describe the distinguishing morphologic characteristics, clinical disease, basics of life cycle (source, stages of infectivity), and laboratory diagnosis for amebae, flagellates, and coccidia.

2. Compare and contrast the morphologic forms of the Naegleria trophozoites including specimens used for identification.

3. Compare and contrast Naegleria fowleri, Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Ancanthamoeba spp. including routes of transmission, specimens, risk factors, and disease presentation.

4. Compare and contrast the specimen requirements and morphologic characteristics of Pentatrichomonas hominis and Trichomonas vaginalis.

5. Identify the various morphologic forms of Toxoplasma gondii and correlate those with the clinical presentation of the infection (acute, chronic, and congenital).

6. Describe the various individual populations at risk for infection with Toxoplasma spp. and the disease symptoms and pathogenesis for each.

7. Define the following terms in relationship to the appropriate parasite discussed in this chapter: axostyle, bradyzoite, tachyzoite, ectocyst, mesocyst, endocyst, and oocyst.

Naegleria Fowleri

General Characteristics

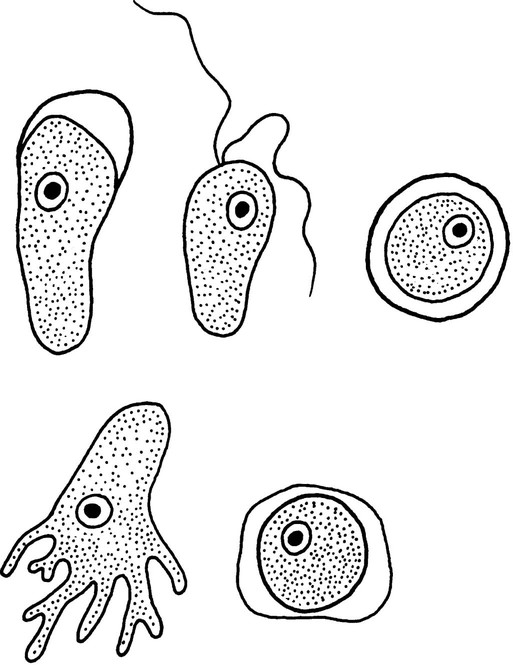

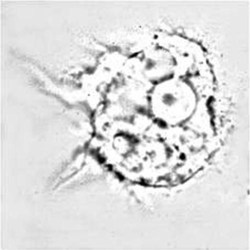

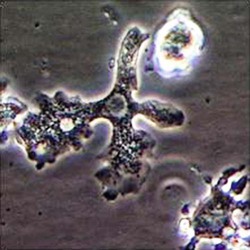

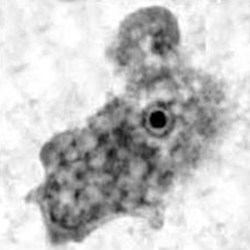

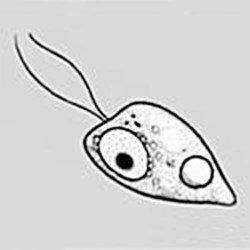

The trophozoites can occur in two forms: ameboid and flagellate (Table 50-1, Figure 50-1). The size ranges from 7 to 35 µm. The diameter of the rounded forms is usually 15 µm. There is a large, central karyosome and no peripheral nuclear chromatin. The cytoplasm is somewhat granular and contains vacuoles. The ameboid form organisms change to the transient, pear-shaped flagellate form when they are transferred from culture or teased from tissue into water and maintained at a temperature of 27° to 37° C. These flagellate forms do not divide, but when the flagella are lost, the ameboid forms resume reproduction. Cysts are generally round, measuring from 7 to 15 µm with a thick double wall.

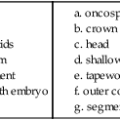

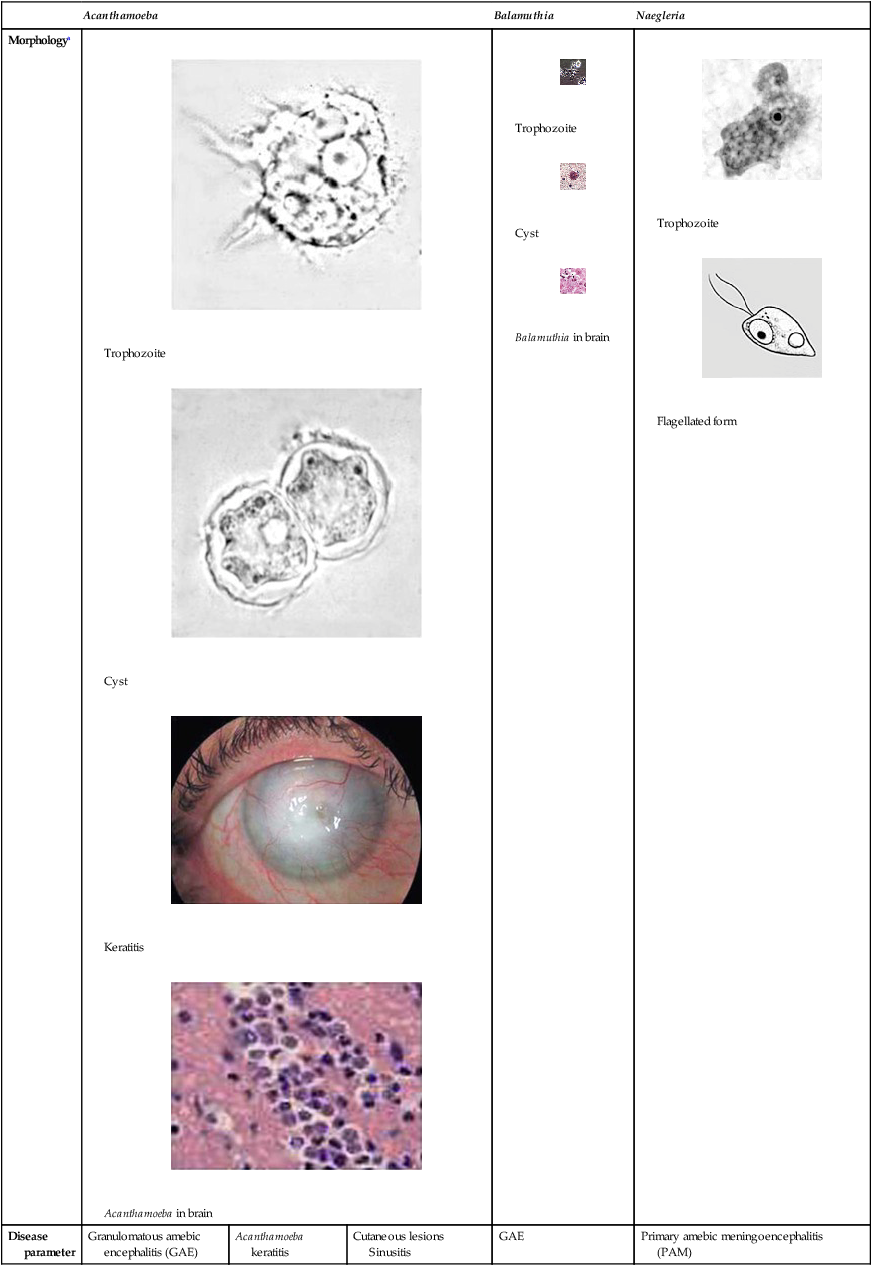

TABLE 50-1

Free-Living Amebae Causing Disease in Humans

| Acanthamoeba | Balamuthia | Naegleria | |||

| Morphologya |

Trophozoite  Cyst  Keratitis  Acanthamoeba in brain |

Trophozoite  Cyst  Balamuthia in brain |

Trophozoite  Flagellated form |

||

| Disease parameter | Granulomatous amebic encephalitis (GAE) | Acanthamoeba keratitis | Cutaneous lesions Sinusitis |

GAE | Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) |

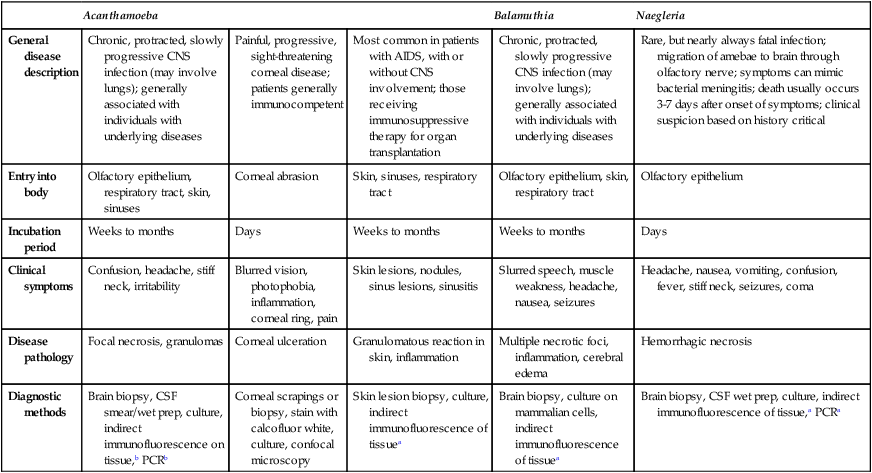

| General disease description | Chronic, protracted, slowly progressive CNS infection (may involve lungs); generally associated with individuals with underlying diseases | Painful, progressive, sight-threatening corneal disease; patients generally immunocompetent | Most common in patients with AIDS, with or without CNS involvement; those receiving immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation | Chronic, protracted, slowly progressive CNS infection (may involve lungs); generally associated with individuals with underlying diseases | Rare, but nearly always fatal infection; migration of amebae to brain through olfactory nerve; symptoms can mimic bacterial meningitis; death usually occurs 3-7 days after onset of symptoms; clinical suspicion based on history critical |

| Entry into body | Olfactory epithelium, respiratory tract, skin, sinuses | Corneal abrasion | Skin, sinuses, respiratory tract | Olfactory epithelium, skin, respiratory tract | Olfactory epithelium |

| Incubation period | Weeks to months | Days | Weeks to months | Weeks to months | Days |

| Clinical symptoms | Confusion, headache, stiff neck, irritability | Blurred vision, photophobia, inflammation, corneal ring, pain | Skin lesions, nodules, sinus lesions, sinusitis | Slurred speech, muscle weakness, headache, nausea, seizures | Headache, nausea, vomiting, confusion, fever, stiff neck, seizures, coma |

| Disease pathology | Focal necrosis, granulomas | Corneal ulceration | Granulomatous reaction in skin, inflammation | Multiple necrotic foci, inflammation, cerebral edema | Hemorrhagic necrosis |

| Diagnostic methods | Brain biopsy, CSF smear/wet prep, culture, indirect immunofluorescence on tissue,b PCRb | Corneal scrapings or biopsy, stain with calcofluor white, culture, confocal microscopy | Skin lesion biopsy, culture, indirect immunofluorescence of tissuea | Brain biopsy, culture on mammalian cells, indirect immunofluorescence of tissuea | Brain biopsy, CSF wet prep, culture, indirect immunofluorescence of tissue,a PCRa |

aAcanthamoeba in brain and Balamuthia in brain courtesy Dr. Govinda Visvesvara, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

bIndirect immunofluorescence on tissue and PCR methods available from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) caused by N. fowleri is an acute, suppurative infection of the brain and meninges (Figure 50-2). With extremely rare exceptions, the disease is rapidly fatal in humans. The period between organism contact and onset of symptoms such as fever, headache, and rhinitis varies from a few days to 2 weeks. Early symptoms include vague upper respiratory tract distress, headache, lethargy, and occasionally olfactory problems. The acute phase includes sore throat; a stuffy, blocked, or discharging nose; and severe headache. Progressive symptoms include pyrexia, vomiting, and stiffness of the neck. Mental confusion and coma usually occur approximately 3 to 5 days before death, which is usually caused by cardiorespiratory arrest and pulmonary edema.

Trichomonas Vaginalis

General Characteristics

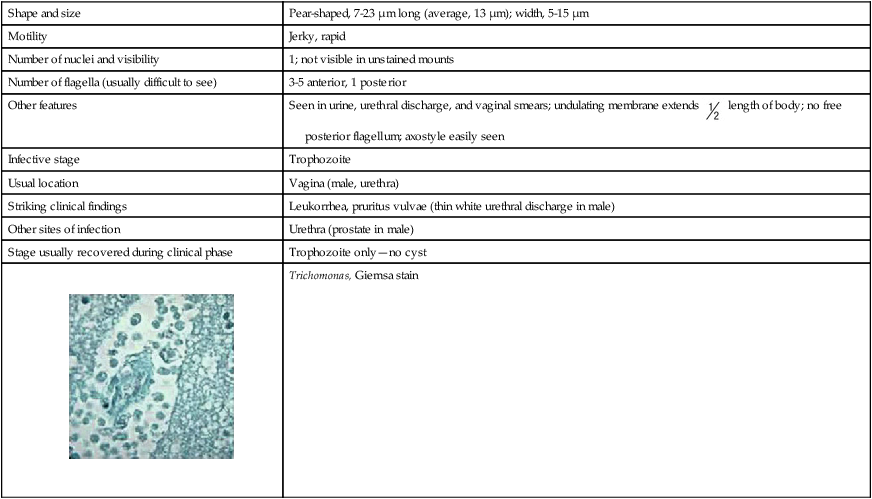

The life cycle of T. vaginalis has a single trophozoite stage, and is very similar in morphology to other trichomonads (Table 50-2). The trophozoite is 7 to 23 µm long and 5 to 15 µm wide. The axostyle is usually obvious and protrudes through the bottom of the organism, whereas the undulating membrane ends halfway down the side of the trophozoite. There are a large number of granules evident along the axostyle.

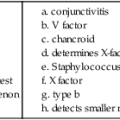

TABLE 50-2

Characteristics of Trichomonas vaginalis

| Shape and size | Pear-shaped, 7-23 µm long (average, 13 µm); width, 5-15 µm |

| Motility | Jerky, rapid |

| Number of nuclei and visibility | 1; not visible in unstained mounts |

| Number of flagella (usually difficult to see) | 3-5 anterior, 1 posterior |

| Other features | Seen in urine, urethral discharge, and vaginal smears; undulating membrane extends  length of body; no free posterior flagellum; axostyle easily seen length of body; no free posterior flagellum; axostyle easily seen |

| Infective stage | Trophozoite |

| Usual location | Vagina (male, urethra) |

| Striking clinical findings | Leukorrhea, pruritus vulvae (thin white urethral discharge in male) |

| Other sites of infection | Urethra (prostate in male) |

| Stage usually recovered during clinical phase | Trophozoite only—no cyst |

|

Trichomonas, Giemsa stain |

Toxoplasma Gondii

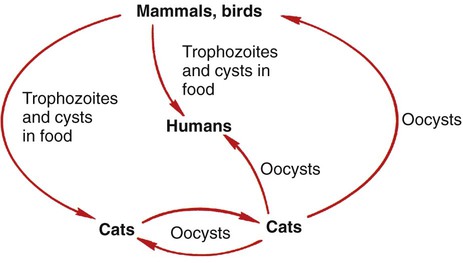

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan parasite that infects most species of warm-blooded animals, including humans. Members of the cat family, Felidae, are the only known definitive hosts for the sexual stages of T. gondii and serve as the main reservoirs of infection. Cats become infected with T. gondii through carnivorism or by ingestion of oocysts. Outdoor cats are much more likely to become infected than domestic cats that are confined indoors. After tissue cysts or oocysts are ingested by the cat, organisms are released and invade epithelial cells of the cat small intestine, where they undergo an asexual cycle followed by a sexual cycle with the formation of oocysts, which are excreted in the feces. The uninfective oocyst takes 1 to 5 days after excretion to become infective. Cats shed oocysts for 1 to 2 weeks and large numbers may be shed, often more than 100,000 per gram of feces. Oocysts survive in the environment for several months to more than 1 year and are resistant to disinfectants, freezing, and drying. However, they are killed by heating to 70° C for 10 minutes. The life cycle in the cat takes approximately 19 to 48 days after infection with the oocysts but only 3 to 10 days after the ingestion of meat infected with cysts (e.g., a mouse) (Figure 50-3).

General Characteristics

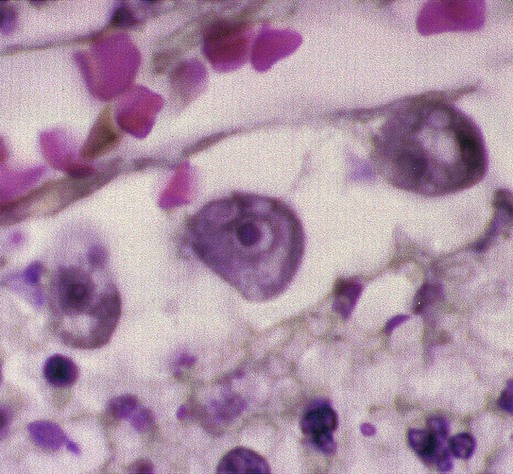

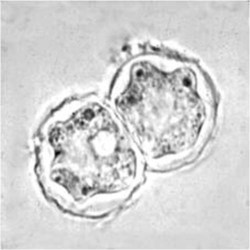

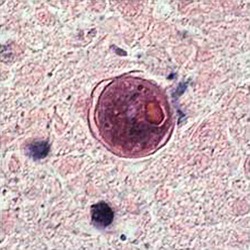

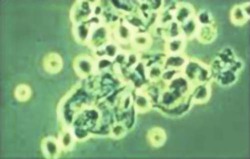

Tachyzoites are crescent-shaped and are 2 to 3 µm wide by 4 to 8 µm long (Table 50-3). One end tends to be more rounded than the other. Giemsa is the stain of choice; the cytoplasm stains pale blue, and the nucleus stains red and is situated toward the broad end of the organism.

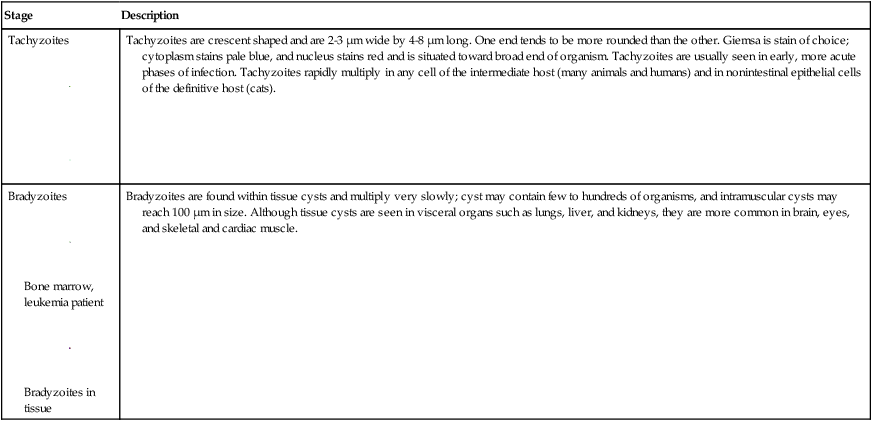

TABLE 50-3

Morphology of Toxoplasma gondii Stages Found in Humans

| Stage | Description |

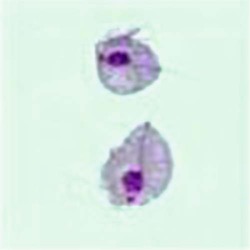

Tachyzoites

|

Tachyzoites are crescent shaped and are 2-3 µm wide by 4-8 µm long. One end tends to be more rounded than the other. Giemsa is stain of choice; cytoplasm stains pale blue, and nucleus stains red and is situated toward broad end of organism. Tachyzoites are usually seen in early, more acute phases of infection. Tachyzoites rapidly multiply in any cell of the intermediate host (many animals and humans) and in nonintestinal epithelial cells of the definitive host (cats). |

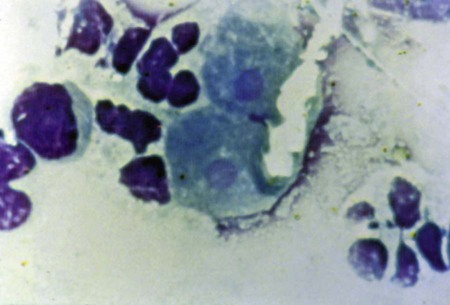

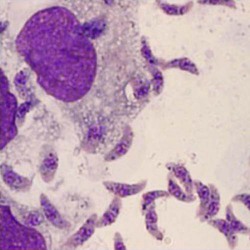

Bradyzoites

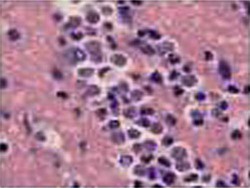

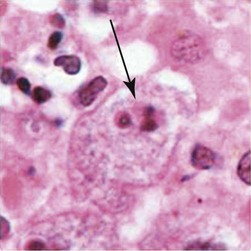

Bone marrow, leukemia patient  Bradyzoites in tissue |

Bradyzoites are found within tissue cysts and multiply very slowly; cyst may contain few to hundreds of organisms, and intramuscular cysts may reach 100 µm in size. Although tissue cysts are seen in visceral organs such as lungs, liver, and kidneys, they are more common in brain, eyes, and skeletal and cardiac muscle. |

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Diagnosis and their interpretations may differ for each clinical category.

Immunocompromised Individuals

Infections in the compromised patient can lead to severe complications (Table 50-4). Underlying conditions that may impact the disease outcome include Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, leukemia, solid tumors, collagen vascular disease, organ transplantation, and AIDS. In the immunocompromised patient, the CNS is primarily involved, but these patients may also have myocarditis or pneumonitis. More than 50% of these patients will show altered mental state, motor impairment, seizures, abnormal reflexes, and other neurologic sequelae. Toxoplasmosis in patients being treated with immunosuppressive drugs may be due to either newly acquired or reactivated latent infection.

TABLE 50-4

People at Risk for Severe Toxoplasmosis

| Category | Comments |

| Infants born to mothers who are first exposed to Toxoplasma infection several months before or during pregnancy | Mothers who are first exposed to Toxoplasma more than 6 months before becoming pregnant are not likely to pass infection to their children |

| Persons with severely weakened immune systems | Infection that occurred at any time during life can reactivate in an immunocompromised individual |

Laboratory Diagnosis

The serologic diagnosis of toxoplasmosis is very complex and has been discussed extensively in the literature (Wilson & McAuley, 2003); a number of additional procedures include enzyme immunoassays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs), direct agglutination, an immunosorbent agglutination assay, an indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), immunocapture, and immunoblot tests.