Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by compromised bone strength, which predisposes to the development of fragility fractures. Bone strength is determined by both bone mass and bone quality. The diagnosis of osteoporosis is established by the presence of a true fragility or, in patients who have never sustained a fragility fracture, by measurement of bone mineral density (BMD).

2. What are fragility fractures?

Fragility fractures are fractures that occur spontaneously or following minimal trauma, defined as falling from a standing height or less. Fractures of the vertebrae, hips, and distal radius (Colles fracture) are the most characteristic fragility fractures, but patients with osteoporosis are prone to all types of fractures. Osteoporosis accounts for approximately 1.5 million fractures in the United States each year.

3. What are the complications of osteoporotic fractures?

Vertebral fractures cause loss of height, anterior kyphosis (dowager’s hump), reduced pulmonary function, and an increased mortality rate. Approximately one third of all vertebral fractures are painful, but two thirds are asymptomatic. Hip fractures are associated with permanent disability in nearly 50% of patients and with a 20% higher mortality rate than in the age-matched population without fractures.

4. What factors contribute most to the risk of an osteoporotic fracture?

Low BMD (twofold increased risk for every one standard deviation [SD] decrease of BMD)

Low BMD (twofold increased risk for every one standard deviation [SD] decrease of BMD)

Age (twofold increased risk for every decade of age above 60 years)

Age (twofold increased risk for every decade of age above 60 years)

Previous fragility fracture (fivefold increased risk for a previous fracture)

Previous fragility fracture (fivefold increased risk for a previous fracture)

5. What are the currently accepted indications for BMD measurement?

Estrogen deficiency plus one risk factor for osteoporosis

Estrogen deficiency plus one risk factor for osteoporosis

Vertebral deformity, fracture, or radiographic evidence of osteopenia

Vertebral deformity, fracture, or radiographic evidence of osteopenia

Glucocorticoid therapy, ≥ 5 mg/day of prednisone for ≥ 3 months

Glucocorticoid therapy, ≥ 5 mg/day of prednisone for ≥ 3 months

Monitoring the response to an osteoporosis medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Monitoring the response to an osteoporosis medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

6. How is BMD currently measured?

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the most accurate and widely used method in current practice. BMD can also be measured by computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound (US). Central densitometry measurements (spine and hip) are the best predictors of fracture risk and have the best precision for longitudinal monitoring. Peripheral densitometry measurements (heel, radius, hands) are more widely available and less expensive.

7. How do you read a bone densitometry report?

T-score: The number of SDs the patient’s value is below or above the mean value for young normal subjects (peak bone mass). The T-score is a good predictor of the fracture risk.

T-score: The number of SDs the patient’s value is below or above the mean value for young normal subjects (peak bone mass). The T-score is a good predictor of the fracture risk.

Z-score: The number of SDs the patient’s value is below or above the mean value for age-matched normal subjects. The Z-score indicates whether or not the BMD is appropriate for age.

Z-score: The number of SDs the patient’s value is below or above the mean value for age-matched normal subjects. The Z-score indicates whether or not the BMD is appropriate for age.

Absolute BMD: The actual BMD expressed in g/cm2. This is the value that should be used to calculate changes in BMD during longitudinal follow-up.

Absolute BMD: The actual BMD expressed in g/cm2. This is the value that should be used to calculate changes in BMD during longitudinal follow-up.

8. How is the diagnosis of osteoporosis made?

Osteoporosis should be diagnosed in any patient who sustains a fragility fracture. In a patient without fractures, the diagnosis can be made on the basis of the BMD T-score at the lowest skeletal site, using the following criteria:

9. What are the major risk factors for the development of osteoporosis?

| Non-modifiable risk factors | Age |

| Race (Caucasian, Asian) | |

| Female gender | |

| Early menopause | |

| Slender build | |

| Positive family history | |

| Modifiable risk factors | Low calcium intake |

| Low vitamin D intake | |

| Estrogen deficiency | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Alcohol excess (> 2 drinks/day) | |

| Caffeine excess (> 2 servings/day) |

10. What other conditions must be considered as causes of low BMD?

11. Outline a cost-effective evaluation to rule out other causes of low bone mass.

Creatinine (estimated glomerular filtration rate)

Creatinine (estimated glomerular filtration rate)

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

Celiac disease antibody testing

Celiac disease antibody testing

Urine (24-hour) calcium, sodium, creatinine

Urine (24-hour) calcium, sodium, creatinine

In approximately one third of women and two thirds of men, an abnormality will be detected with this evaluation.

12. How do you determine whether a patient has had a previous vertebral fracture?

Back pain and tenderness are helpful clues but may be absent because two thirds of vertebral fractures are asymptomatic. Height loss of 2 inches or more and dorsal kyphosis are highly suggestive clinical findings. Lateral spine films and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) are the most accurate ways to detect existing vertebral fractures.

13. What are the most significant risk factors for frequent falls?

14. What non-pharmacologic measures help to prevent and treat osteoporosis?

Adequate calcium intake (diet plus supplements): 1000-1200 mg/day for premenopausal women and men; 1200-1500 mg/day for postmenopausal women and men 65 years or older

Adequate calcium intake (diet plus supplements): 1000-1200 mg/day for premenopausal women and men; 1200-1500 mg/day for postmenopausal women and men 65 years or older

Adequate vitamin D intake: 800-1200 U/day (D3 preferred)

Adequate vitamin D intake: 800-1200 U/day (D3 preferred)

Regular exercise: aerobic and resistance

Regular exercise: aerobic and resistance

Limitation of alcohol consumption to fewer than 2 drinks/day

Limitation of alcohol consumption to fewer than 2 drinks/day

Limitation of caffeine consumption to fewer than 2 servings/day

Limitation of caffeine consumption to fewer than 2 servings/day

15. How can dietary calcium intake be accurately assessed?

The major bioavailable sources are dairy products and calcium-fortified fruit drinks. The following approximate calcium contents should be assigned for dairy product intake:

Add 300 mg for the general nondairy diet for a reasonable estimate of daily intake.

16. How do you ensure adequate intake of calcium?

Low-fat dairy products are the best source of calcium. Calcium supplements should be added when the desired goals cannot be reached with dietary sources. Calcium carbonate and calcium citrate are both well absorbed when taken with meals. Gastric acid is needed for normal calcium absorption; calcium carbonate absorption may be significantly reduced in patients who have achlorhydria or who use a PPI. Calcium citrate absorption is less likely to be affected by PPI use.

17. What are the best ways achieve adequate vitamin D intake?

There are two natural forms of vitamin D: cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) and ergocalciferol (vitamin D2). Fatty fish (D3) and some fortified milk and cereal products (D2 and D3) are good dietary sources. Vitamin D2 and D3 supplements are available over the counter in multiple doses, and 50,000-unit vitamin D2 supplements can be given by prescription. Sunlight exposure raises vitamin D levels but often must be limited for many reasons; therefore, oral vitamin D is the major source for most people. The optimal vitamin D intake is 800 to 1200 units daily.

18. How do you treat patients with vitamin D deficiency?

The serum 25-OHD goal level is 30 to 100 ng/mL. In general, 1000 units (U) daily of vitamin D will raise the serum level by 10 ng/mL. I recommend the following:

| 25-OHD LEVEL (NG/ML) | MANAGEMENT |

| 20-30 | 2000 U D3 daily |

| 10-20 | 50,000 U D2 weekly for 3 months, then 2000 U D3 daily |

| < 10 | 50,000 U D2 twice weekly for 3 months, then 2000 U D3 daily |

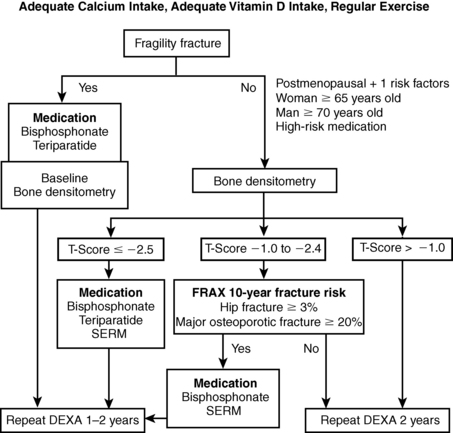

19. When should pharmacologic therapy be initiated for osteoporosis?

Pharmacologic therapy should be advised for anyone who has had a vertebral or hip fracture or who has a T-score less than −2.5. The FRAX tool, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), is recommended for making treatment decisions in drug-naïve patients with osteopenia (for information, go to www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX). Treatment is advised for those who have a 10-year risk of 3% or higher for hip fracture or 20% or higher for other major osteoporotic fractures.

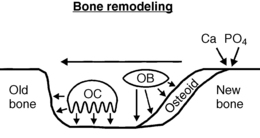

Bone remodeling is the process that removes old bone and replaces it with new bone (Fig. 8-1). Osteoclasts attach to bone surfaces and secrete acid and enzymes that dissolve away underlying bone. Osteoblasts then migrate into these resorption pits and secrete osteoid, which becomes mineralized with calcium phosphate crystals (hydroxyapatite). Osteocytes serve as the mechanoreceptors that sense skeletal stress and send signals to orchestrate the process of bone remodeling in areas of bone that need renewal.

21. What are RANK, RANK-L, and Osteoprotegerin?

RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor κ) is a specific receptor on osteoclasts. RANK-L (RANK ligand) binds to RANK to stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption. Osteoprotegerin is a soluble decoy receptor that binds to RANK-L, preventing it from binding to RANK. Bone resorption is driven by RANK-L and inhibited by osteoprotegerin.

22. How do the pharmacologic agents for osteoporosis work?

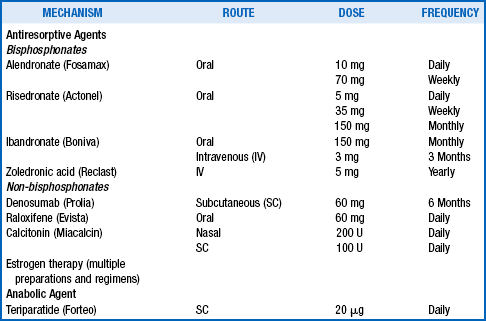

Osteoporosis medications are classified into two main categories: antiresorptive agents and anabolic agents. Antiresorptive medications include the bisphosphonates, denosumab (monoclonal antibody against RANK-L), raloxifene, calcitonin, and estrogens. The only currently available anabolic agent is teriparatide.

23. What pharmacologic agents are FDA approved and how are they used?

24. How could teriparatide be an anabolic agent for treating osteoporosis?

Persistently elevated serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (primary hyperparathyroidism) promote osteoclastic bone resorption and bone loss. In contrast, intermittent daily pulses of exogenous PTH actually stimulate osteoblastic bone formation and increase bone mass. Teriparatide is a 34–amino acid fragment of intact PTH that retains the ability to bind to and activate PTH receptors on osteoblasts.

25. Have all of these medications been shown to prevent fractures?

All of the FDA-approved medications listed in the previous table have been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to significantly reduce vertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Hip fractures have also been reduced by alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Nonvertebral fracture reduction has been reported with alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, denosumab, and teriparatide.

26. Are medication combinations more effective than single agents?

Combinations of antiresorptive agents increase bone mass more than single agents alone, but fracture data are not yet available for such regimens. Furthermore, there are concerns that oversuppression of bone resorption may be harmful. Combinations of anabolic and antiresorptive agents used concurrently have disappointingly shown no greater effects than single agents alone. Studies investigating sequential rather than concurrent use of various agents are currently in progress.

27. Is osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) related to bisphosphonate therapy?

ONJ manifests as persistently exposed bone following an invasive dental procedure. It occurs most often during high-dose IV bisphosphonate therapy for multiple myeloma or bone metastases. ONJ has also been identified in some patients taking bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Good oral hygiene and regular dental care are the best preventive measures. Temporarily stopping bisphosphonates for invasive dental procedures is a common and reasonable practice but has not been shown to prevent ONJ.

28. What about atypical femoral fractures with bisphosphonate use?

Atypical femoral fractures have been reported in some patients undergoing long-term bisphosphonate therapy (> 5 years). It is not clear whether the fractures resulted from bisphosphonate use or the underlying osteoporosis. Currently, no data exist regarding preventive measures. After 5 years of bisphosphonate use, many providers recommend a 1- to 2-year bisphosphonate “drug holiday” for patients who have osteopenia and a temporary switch to anabolic therapy or other non-bisphosphonate agent for those with previous fractures or very low BMD.

29. How should BMD be used to monitor the response to osteoporosis therapy?

BMD testing to monitor therapy responses is most often repeated after 2 years of treatment. To accurately interpret serial changes, the least significant change (LSC) for the specific instrument must be known. The LSC is a precision estimate that informs the user about the minimum BMD change that should be considered significant. Standard procedures for performing the LSC assessment are available on the International Society for Clinical Densitometry’s Website (www.iscd.org).

30. How do you interpret BMD changes in patients taking osteoporosis medications?

| BMD CHANGE | INTERPRETATION | RECOMMENDED ACTION |

| Increase ≥ LSC | Good response | Continue therapy |

| No change or < LSC | Adequate response | Continue therapy |

| Decrease ≥ LSC | Treatment failure | Evaluate; consider therapy change |

31. What markers are available to assess bone remodeling, and how are they used?

| Markers of bone formation | Serum alkaline phosphatase |

| Serum osteocalcin | |

| Markers of bone resorption | Urine or serum N-telopeptides |

| Serum C-telopeptides |

Elevation of biomarkers predicts future bone loss. A 30% reduction of biomarkers after therapy is initiated verifies compliance and predicts an increase in bone mass. However, great variability in biomarker measurement limits the utility of this tool.

32. What do you do when BMD falls significantly during osteoporosis therapy?

| CAUSE | MANAGEMENT |

| Nonadherence | Encourage adherence |

| Calcium deficiency | Ensure adequate calcium intake |

| Vitamin D deficiency | Ensure adequate vitamin D intake |

| Secondary bone loss | Treat the cause |

| Treatment failure | Change medication |

33. How does osteoporosis differ in men?

Approximately 1 to 2 million men in the United States have osteoporosis. The diagnostic criteria are the same in men as in women (fragility fracture or T-score ≤ −2.5). Nearly two thirds of osteoporotic men have an identifiable secondary cause of bone loss, most often alcohol abuse, glucocorticoid use, or hypogonadism, including that due to use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analog for prostate cancer. Treatment is generally the same as in women although testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men can be an effective adjunctive strategy.

34. How can falls be prevented?

1. Minimize or discontinue sedatives.

3. Prescribe ambulatory aids when appropriate.

4. Make a “fall-proof” home: adequate lighting, carpeting, handrails, non-slip bathroom surfaces, removal of clutter and obstacles to walking.

Figure 8-2. Osteoporosis management algorithm.

35. Outline an efficient and effective management strategy for a patient with osteoporosis.

Abrahamsen, B, Eiken, P, Eastell, R, Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate. a register-based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:1095–1102.

Black, DM, Cummings, SR, Karpf, DB, et al. Randomized trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. (FIT 1). Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541.

Black, DM, Delmas, PD, Eastell, R, et al. Once yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;356:1809–1822.

Black, DM, Kelly, MP, Genant, HK, et al. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1761–1771.

Black, DM, Schwartz, AV, Ensrud, KE, et al, Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment. the Fracture Intervention Trial Long Term Extension (FLEX), a randomized trial, JAMA 2006;296:2927–2938.

Bonnick, S, Johnston, CC, Kleerekoper, M, et al. Importance of precision in bone density measurements. J Clin Densitom. 2001;4:1–6.

Canalis, E, Giustina, A, Bilezikian, JP. Mechanisms of anabolic therapies for osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:905–916.

Chesnut, CH, Silverman, S, Andriano, K, et al, A randomized trial of nasal spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis. the Prevent Recurrence of Osteoporotic Fractures Study. Am J Med 2000;109:267–276. (PROOF)

Cummings, SR, Palermo, L, Browner, W, et al. Monitoring osteoporosis therapy with bone densitometry. JAMA. 2000;283:1318–1321.

Cummings, SR, San Martin, J, McClung, MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756–764.

Dawson-Hughes, B, Bischoff-Ferrari, HA. Therapy of osteoporosis with calcium and vitamin D. J Bone Min Res. 2007;22:V59–63.

Delmas, PD, Recker, RR, Chesnut, CH, et al, Daily and intermittent oral ibandronate normalize bone turnover and provide significant reduction in vertebral fracture risk. results from the BONE study. Osteoporosis Int 2004;15:792–798.

Ettinger, B, Black, DM, Mitlak, BH, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene. (MORE). JAMA. 1999;282:637–645.

Fauvus, MJ. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2027–2035.

Harris, ST, Watts, NB, Genant, HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. A randomized controlled trial. (VERT-NA). JAMA. 1999;282:1344–1352.

Heaney, RP, Recker, RR, Weaver, CM, Absorbability of calcium sources. the limited role of solubility. Calcif Tissue Int 1990;46:300–304.

Heaney, RP. Vitamin D endocrine physiology. J Bone Min Res. 2007;22:V25–27.

Holick, MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281.

Jones, G, Horst, R, Carter, G, et al. Contemporary diagnosis and treatment of vitamin D related disorders. J Bone Min Res. 2007;22:V11–15.

Khosla, S, Burr, D, Cauley, J, et al, Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Min Res 2007;22:1479–1491.

Khosla, S, Melton, LJ. Osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2293–2300.

Lewiecki, EM. Nonresponders to osteoporosis therapy. J Clin Densitom. 2003;6:307–314.

Lindsay, R, Silverman, SL, Cooper, C, et al. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001;285:320–323.

Lyles, KW, Colon-Emeric, CS, Magaziner, JS, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799–1809.

McClung, MR, Geusens, P, Miller, PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. (HIP). N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340.

McClung, MR, Lewiecki, EM, Cohen, SB, et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:821–831.

Neer, RM, Arnaud, CD, Zanchetta, JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441.

Neviaser, AS, Lane, JM, Lenart, BA, et al. Low-energy femoral shaft fractures associated with alendronate use. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:346–350.

Orwoll, E, Ettinger, M, Weiss, S, et al. Alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:604–610.

Orwoll, E, Scheele, WH, Paul, S, et al. The effect of teriparatide [human parathyroid hormone (1-34)] therapy on bone density in men with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:9–17.

Orwoll, ES. Osteoporosis in men. Osteoporosis. 1998;27:349–367.

Painter, SE, Kleerekoper, M, Camacho, PM, Secondary osteoporosis. a review of the recent evidence. Endocr Pract 2006;12:436–445.

Recker, RR. Calcium absorption and achlorhydria. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:70–73.

Rittmaster, RS, Bolognese, M, Ettinger, MP, et al. Enhancement of bone mass in osteoporotic women with parathyroid hormone followed by alendronate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2129–2134.

Shoback, D. Update in osteoporosis and metabolic bone disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:747–753.

Targownik, LE, Lix, LM, Tetge, CJ, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179:319–326.

Visekruna, M, Wilson, D, McKierman, FE. Severely suppressed bone turnover and atypical skeletal fragility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2948–2952.

Woo, SB, Hellstein, JW, Kalmar, JR, Systemic review. bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:753–761.

, Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risk and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321–333.

Yang, YX, Lewis, JD, Epstein, S, et al. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fractures. JAMA. 2006;296:2947–2953.