Chapter 36 Osteochondral Grafts

Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Hyaline articular cartilage is an avascular and insensate tissue that allows low-friction transmission of physiologic loads in diarthrodial joints. Its functional structure ideally is maintained in homeostasis over the lifetime of an individual, but remains incapable of mounting an effective repair response when injured in the skeletally mature adult.10,35 The treatment threshold for surgical intervention is not unequivocal, but patients with symptomatic lesions are generally considered candidates for cartilage restoration procedures.3

The use of osteochondral grafts of autologous or allogeneic origin is well supported on a basic science level and has a long successful clinical history as a means of biologic resurfacing.9,16 Both modalities rely on transplanting mature hyaline cartilage containing viable chondrocytes attached to subchondral bone to restore the architecture and characteristics of native tissue in acquired osteoarticular defects. By transplanting structurally complete osteochondral units with an intact tidemark, the fixation issue is mostly relegated to that of osseous ingrowth.31 Whereas both graft sources represent a common cartilage organ transplantation paradigm and are complementary, each has its unique, reciprocal challenges with regard to tissue availability and safety that must be weighed, managed, and communicated whenever the use of osteochondral grafts is being considered.

INDICATIONS

Autografts

In the authors’ hands, autologous grafts are best used to address relatively small, yet symptomatic, focal articular lesions of the femoral condyles, especially if these present with associated subchondral abnormalities such as a bone cyst or an intralesional osteophyte. Autologous plugs are also a potential salvage option as in situ fixation for a delaminating osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesion (International Cartilage Repair Society [ICRS] grade II–IV, see Chapter 47, Articular Cartilage Rating Systems).19,41

Advantages of autologous grafts are immediate availability, relatively low cost, and their nonantigenic and osteogenic behavior that routinely lead to reliable osteointegration.11 The possibility of arthroscopic delivery of these smaller grafts is appealing, albeit technically challenging.

One obvious disadvantage of autologous graft sources is that the maximum graft surface area is self-limited by donor volume or lack thereof, for small and at most medium-sized lesions. This is especially true in the previously injured and/or operated knee, in which suitability regarding tissue quality and overall joint topography has to be critically assessed. In addition, donor-site morbidity can significantly add to the disease burden during intra-articular transfer.9

Allografts

Osteochondral allografts are ideally suited to treat medium to large chondral and osteochondral lesions.24 In particular, osteochondral allografting may be considered the current “gold standard” treatment for high-grade (ICRS grade III–IV) OCD about the knee. Other specific conditions amenable to allografting include osteonecrosis and post-traumatic defects, such as after periarticular fractures. Further indications for allografting of the knee include treatment of patellofemoral chondrosis or arthrosis and highly select cases of multifocal or bipolar post-traumatic or degenerative lesions. In a case in which meniscus replacement is also necessary, a composite tibial plateau with attached meniscus can be transplanted. Allografts are also increasingly employed in the salvage of knees that have failed other cartilage resurfacing procedures. Primary treatment may be considered in large chondral defects, whose size presents a relative contraindication for other treatments and for which the surgeon believes other procedures may be inadequate.

Osteochondral allografting is the only treatment option that restores mature orthotopic hyaline cartilage and reproduces the site-appropriate anatomy of the native joint both macroscopically and microscopically, without the risk of inducing donor-site morbidity.23 Osteochondral allografts are versatile addressing even very large, complex, or multiple lesions in topographically challenging environments, especially if they involve an osseous component.

Obvious drawbacks to the allograft paradigm are the relative scarcity of donor tissue, financial and logistical issues of graft procurement, and residual risk of infection, a discussion that is an essential part of the informed consent process.24 Although rare allograft-associated bacterial infections have been reported,49 there are no available published data quantifying this risk or that of viral transmission. Patients are counseled that the risk for disease transmission from a fresh osteochondral allograft is comparable with that associated with banked blood transfusion. In a 30-year experience at the authors’ institution, using over 500 fresh allografts, no cases of transmission of disease from donor to recipient have been documented.

Fresh, cold-stored osteochondral allografts have shown to maintain viable chondrocytes and mechanical properties of the matrix many years after transplantation.4,14–16,30,38,52 These findings have generally supported the use of tissue for small osteochondral allografts in the setting of reconstruction of chondral and osteochondral defects. Chondrocyte viability and structural integrity of the matrix are preserved during hypothermal storage in nutritive culture medium containing human serum, with cell density, viability, and metabolic activity remaining essentially unchanged from baseline for as many as 14 days before deteriorating significantly after 28 days while the hyaline matrix remains relatively intact.6,45,47,50,53 The clinical consequences of these storage-induced graft changes have yet to be determined, but 28 days is generally considered the threshold of graft utility in present clinical practice.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

A careful and focused history and physical examination are essential to determine candidacy for any cartilage restoration procedure. Because articular cartilage itself is insensate, it is important to identify contributory pain generators and to distinguish them from mechanical symptoms. Tools such as the ICRS Cartilage Injury Evaluation Package, which incorporates several validated outcome measures, can be helpful in systematically documenting the anatomic condition and functional envelope of the knee and in establishing a baseline for therapy.1

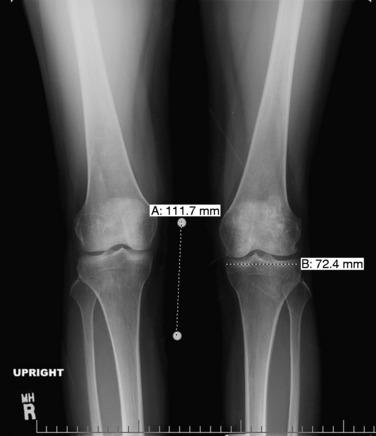

Patients who are considered for an osteochondral grafting procedure should optimally be fully imaged, including a complete radiologic series and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies with cartilage-specific sequencing, if available. Depending on the type and location of cartilage injury being suspected, this should include at least standing anteroposterior (AP) weight-bearing and flexed knee lateral radiographs. Many chondral lesions and their subchondral sequelae are detectable on the AP views (Fig. 36-1), which also give an indication of possible secondary changes such as joint space narrowing and osteophytes. Imaging both knees side-by-side allows for a built-in comparison view. Of note, OCD presents with bilateral lesions in about a third of cases that are often easily detected on an x-ray in their typical location on the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle toward the intercondylar notch. The lateral flexed view is an important supplementary tool to help assess lesion size, triangulate locations, and identify patient morphology such as patella alta or baja and trochlear groove topography. Additional views that can be obtained include standing posteroanterior 45° flexed knee (Rosenberg) views and supine flexed knee (Merchant) views. The Rosenberg view brings the posterior condyles into view, which helps assess the posterior joint space during loading. Merchant views are standard for the evaluation of the patellofemoral articulation. Long-leg (hip to ankle) standing AP weight-bearing films should be obtained if axial alignment is deemed contributory to the patient’s symptomatology and are essential for preoperative planning if a realignment procedure is being considered.

MRI remains an invaluable tool for assessing the status of the articular cartilage and associated structures of the knee46 (Fig. 36-2). While T2-weighted relaxation time maps are currently recognized as the gold standard for imaging the ultrastructure of the articular cartilage, a standard fat-saturated T2-weighted fast-spin-echo sequence usually conveys sufficient detail on cartilage morphology to guide surgical decision-making and preoperative planning. T1-weighted sequences are generally better suited to assess involvement of the subchondral bone and menisci.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Common to all fresh allografting procedures is matching the donor with the recipient. It should be noted that in current practice, small-fragment fresh osteochondral allografts are not human leukocyte antigen– (HLA-) or blood type–matched between donor and recipient and that no immunosuppression is used. The allografts are matched to recipients on size alone. In the knee, an AP radiograph with a magnification marker is used (see Fig. 36-1), and a measurement of the mediolateral dimension of the tibia, just below the joint surface, is made and corrected for magnification of the radiograph. This corrected measurement is used, and the tissue bank makes a direct measurement on the donor tibial plateau. Alternatively, a measurement of the affected condyle can be performed.28 A match is considered acceptable at ± 2 mm; however, it should be noted that there is a significant variability in anatomy, which is not reflected in size measurements. In particular, in treating OCD, the pathologic condyle is typically larger, wider, and flatter; therefore, a larger donor generally should be used.

Critical Points GENERAL SURGICAL PRINCIPLES OF ALLOGRAFTING

INTRAOPERATIVE PLANNING

Autografting

Historically, the intercondylar notch and lateral trochlea were presumed to be non–load-bearing and thus recommended as donor sites for autologous osteochondral grafting. More recent reports have demonstrated that these areas do bear significant weight, which can theoretically contribute to increased donor-site morbidity. The lateral trochlea appears to be the most involved in loading, followed by the intercondylar notch and the distal medial trochlea.2 Because the lateral trochlea is wider than the medial side, the medial trochlea may best be suited for smaller donor plugs (<5 mm).20 Larger plugs can be taken from the lateral trochlea, starting proximal to the sulcus terminalis, where the lowest contact pressures of the lateral trochlea were measured. Owing to its load-bearing demands, the lateral trochlea appears to have the thicker articular cartilage, making it the favorite graft source of most surgeons. Plugs taken from the far medial and lateral margins of the femoral trochlea, just proximal to the sulcus terminalis, also appear to provide the most accurate reconstruction of the surface anatomy of central lesions in the weight-bearing portion of either femoral condyle.7

Smaller grafts (4 or 6 mm) from the lateral intercondylar notch can also provide precise matches to similar lesions; however, significant inaccuracies are noted when the lateral intercondylar notch grafts are increased in size (8 mm). Whereas all traditional donor sites have less cartilage thickness than common recipient sites, this discrepancy is most profound between the lateral intercondylar notch and the weight-bearing portion of the femoral condyles.48 In addition, the concave central intercondylar notch grafts do not match the topography of the convex femoral condyles,2 and their harvest jeopardizes the integrity of the trochlear subchondral bone, which might be responsible for the increased incidence of anterior knee pain in some studies.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

Autografting

Biomechanical studies have confirmed that optimally sized, level-seated plugs face nearly normal joint contact pressures in situ.34 Results also show that slightly countersunk grafts and angled grafts with the highest edge placed flush to neighboring cartilage demonstrate fairly normal contact pressures. Conversely, elevated angled grafts increase contact pressures as much as 40%, making them biomechanically disadvantageous.33 The general consensus is that it is more favorable to leave a graft slightly countersunk than elevated with respect to the neighboring cartilage.42 The authors thus advise slightly lengthening the recipient tunnel to avoid leaving the graft proud or subjecting it to undue insertion forces in an effort to bury an oversized graft.

Allografting

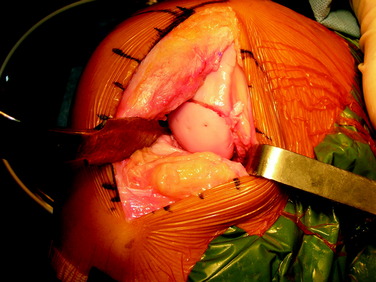

The two commonly used techniques for the preparation and implantation of osteochondral allografts include the press-fit plug technique and the shell-graft technique. Each technique has advantages and disadvantages. The press-fit plug technique is similar in principle to the autologous osteochondral transfer systems described previously. This technique is optimal for contained condylar lesions between 15 and 35 mm in diameter (Fig. 36-3). Fixation is generally not required owing to the stability achieved with the press-fit, unless the lesion falls into the intercondylar notch. Disadvantages include the fact that very posterior femoral and trochlear lesions are not conducive to the use of a circular coring system and may be more amenable to shell allografts. In addition, the more ovoid a lesion in shape, the greater amount of normal cartilage that needs to be sacrificed at the recipient site in order to accommodate the circular donor plug. Shell grafts are technically more difficult to perform and typically require fixation. However, depending on the technique employed, less native host cartilage may need to be sacrificed.

Dowel Allograft

As with autologous dowels, several proprietary instrumentation systems are currently available (Fig. 36-4) for the preparation and implantation of press-fit dowel allografts up to 35 mm in diameter, and surgical techniques are similar.

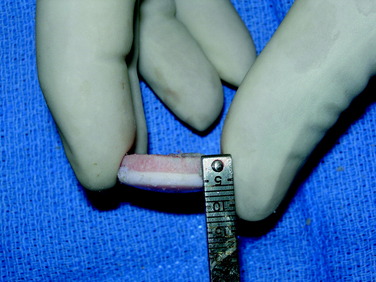

After a size determination is made, a guidewire is driven into the center of the lesion, perpendicular to the curvature of the articular surface. The size of the graft is then determined using sizing dowels, remembering that overlapping dowels (in a “master card” or “snowman” configuration) can possibly deliver the best area fit. The remaining articular cartilage is scored to subchondral bone, and a core reamer is used to remove the articular cartilage remnants and at least 3 to 4 mm of subchondral bone (Fig. 36-5). Because it merely serves as an osteoconductive scaffold for healing to the host by creeping substitution, which is a rate-limited process, the portion of transplanted bone should be minimized wherever possible, without compromising stability of the graft as warranted by the clinical situation (Fig. 36-6). This will also minimize the potential antigenic burden of marrow elements possibly remaining in the transplanted spongiosa.18 In deeper lesions, fibrous and sclerotic bone is removed to a healthy, bleeding osseous base that does not exceed 10 mm in depth. Lesions below this depth should be curetted manually, and packed morselized autologous bone graft should be used to fill any deeper or more extensive osseous defects. Circumferential depth measurements are made of the prepared recipient site after the guide pin has been removed.

The graft is then irrigated copiously with a high-pressure lavage (Fig. 36-7) to remove all marrow elements possible, and the recipient site is dilated using a slightly oversized tamp. This may ease the insertion of the graft to prevent excessive impact loading of the articular surface when the graft is inserted, while compacting the subchondral bone to prevent subsidence of the graft. At this time, any remaining osseous defects are bone-grafted to a level base. The allograft is then inserted by hand in the appropriate rotation and is gently tamped into place until it is flush, again minimizing mechanical insult to the articular surface of both the graft and the surrounding native tissue. Alternatively, the graft can be seated by gently ranging the knee, using the apposing joint surface as a fulcrum.

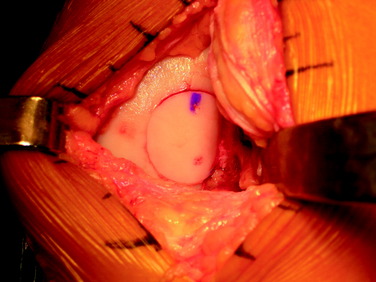

After the graft is seated, additional fixation with absorbable polydioxanone pins may be added if necessary, particularly if the graft is large or has an exposed edge within the notch (Fig. 36-8). The knee is then brought through a complete ROM in order to confirm that the graft is stable and that there is no catching or soft-tissue obstruction noted. The wound is then copiously irrigated, and routine closure is performed.

Shell Allograft

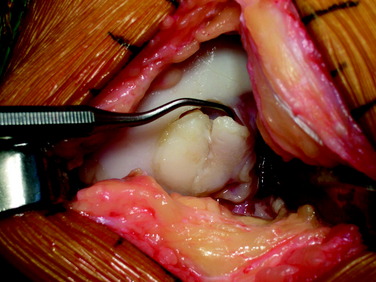

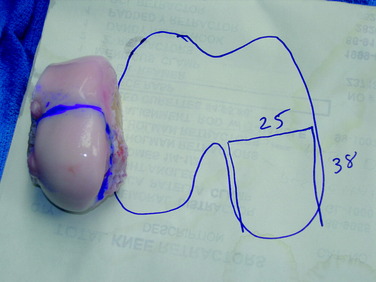

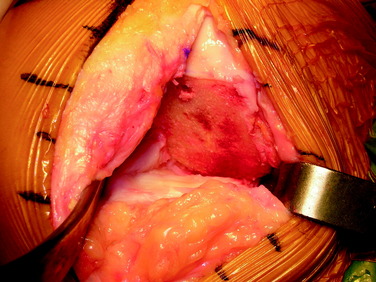

The defect is identified through the previously described arthrotomy, and the dimensions of the lesion are marked with a surgical pen. Minimizing the sacrifice of normal cartilage, a geometric shape is created that is amenable to handcrafting a shell graft (Figs. 36-9 and 36-10). A No. 15 scalpel blade is used to demarcate the lesion, and sharp ring curets are used to remove all tissue inside this mark. Using motorized burrs and sharp curettes, the lesion is débrided down to a depth of 4 to 5 mm (Fig. 36-11). The shape is transferred to the graft, which is molded in a freehand fashion (Fig. 36-12), initially slightly oversizing the graft and carefully removing excess bone and cartilage from the template as necessary through multiple trial fittings. If there is deeper bone loss in the defect, more bone can be left on the graft and the defect can be grafted with cancellous bone prior to graft insertion. The graft and host bed are then copiously irrigated and the graft placed flush with the articular surface. The need for fixation is based on the degree of inherent stability. Bioabsorbable pins, as described previously, are typically used when fixation is required (Fig. 36-13), but countersunk compression screws may be used as an alternative, optimally avoiding the weight-bearing portion. After cycling the knee through a full ROM and irrigating the joint, standard closure is performed.

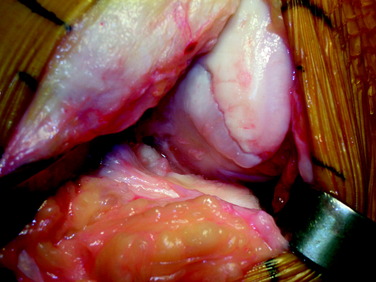

Figure 36-11 Intraoperative view after freehand preparation of the graft bed in preparation for a shell allograft.

AUTHORS’ CLINICAL OUTCOMES

The authors believe that osteochondral allografting is an excellent treatment option for advanced OCD lesions. The authors previously published the results of 66 knees in 64 patients with OCD of the femoral condyle, treated with fresh osteochondral allografts, implanted within 5 days of graft recovery.17 Patients were evaluated pre- and postoperatively using an 18-point modified D’Aubigne and Postel scale, which measures function, ROM, and absence of pain, allotting 1 to 6 points each, for a maximum of 18 points (Table 36-1).

| CRITERIA | ||

|---|---|---|

| Points | PAIN | |

| 1 | Severe | Not relieved by rest and analgesics |

| 2 | Severe | Relieved by rest and analgesics |

| 3 | Moderate | Regular analgesics needed |

| 4 | Mild | Occasional analgesics needed |

| 5 | Minimum | Occasional ache |

| 6 | None | |

| Points | FUNCTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | Bedridden or household walker with two canes or crutches |

| 2 | Time and distance outside limited; walks with external aids |

| 3 | Walks < 0.8 km with external aids; stair climbing limited |

| 4 | Walks > 0.8 km with external aids; stair climbing not limited |

| 5 | No external aids; limps |

| 6 | Unlimited walking without a limp |

| Points | RANGE OF MOTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | <60° of flexion |

| 2 | 15°–90° of flexion |

| 3 | 0°–90° of flexion |

| 4 | >90° of flexion; ≤15° contracture |

| 5 | >90° of flexion without contracture |

| 6 | ≥130° of flexion without contracture |

Whereas OCD remains a perfect indication for osteochondral allografting, focal lesions of diverse etiologies are amenable to this application, and the results were presented of 43 knees with isolated chondral lesions of the femoral condyle.25 Clinical evaluation was performed with the modified D’Aubigne and Postel (18-point) scale. Subjective outcome measures included a patient questionnaire evaluating pain, function, and satisfaction. The study population included 23 males and 20 females, with a mean age of 35 years. Twenty-nine lesions involved the medial femoral condyle, 13 the lateral femoral condyle, and 1 both condyles. All patients had undergone an average of 1.9 previous operations (range, 1–5 operations) before allograft transplantation. The mean allograft area was 5.88 cm2. Of these knees, 38 (88%) were considered successful (score, ≥15 on the 18-point modified D’Aubigne and Postel scale) a mean of 54 months postoperatively. The average score improved from 11.5 points to 16.7 points (P < .05). Fifteen patients had further surgery on the knee, not all related to the allograft: 10 arthroscopies, 3 revision allografts, 1 ACL reconstruction, and 1 osteotomy. Twenty-one of 43 patients completed questionnaires, of which 90% were satisfied and 90% reported less pain and improved function. In conclusion, fresh osteochondral allografting was successful in 88% of patients and resulted in significant improvement in function and pain with high patient satisfaction. Osteochondral allografting is a reasonable option for patients with cartilage lesions of the femoral condyle, especially in a salvage situation after prior failure of other cartilage procedures.

Osteonecrosis of the knee is a serious potential complication of corticosteroid therapy with limited treatment options. Osteochondral allografting is a salvage alternative in patients who are of an age and activity level not ideally suited for arthroplasty. The authors26 reported the clinical outcomes of fresh osteochondral allografting in individuals with steroid-induced modified Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) stage 3/4 osteonecrosis of the femoral condyles. Clinical evaluation was performed using the modified D’Aubigne and Postel (18-point) scale. Subjective outcome measures included a patient questionnaire evaluating pain, function, and satisfaction. Of 24 patients who underwent osteochondral allografting for osteonecrosis between 1984 and 2005, 17 (12 females and 5 males) fulfilled inclusion criteria with minimum 2-year follow-up (mean follow-up, 65 mo; range, 24–236 mo). The 17 patients had a mean age of 28.8 years (range, 16–68 yr). Five had bilateral surgery, for a total of 22 knees. Of these knees, 16 had unicondylar lesions (12 lateral, 4 medial) and 6 had bicompartmental involvement. Fifty-six percent of knees had previous surgery (average, 1.5; range, 1–5 surgeries). The mean graft surface area was 11.0 cm2 (range, 5.3–19.0 cm2). Twelve of 22 (54.5%) required additional bone grafting. Seventeen of 22 (77%) were considered successful (score, ≥15 points). The mean score improved from 11.1 points to 15.9 points (P < .0001). Two patients had further surgery: 1 underwent arthroscopic débridement and another underwent total knee arthroplasty 76 months after the index surgery. Fourteen patients completed questionnaires; all reported statistically significant higher (P < .0001) pain relief, improved function, and overall satisfaction with their outcome. Fresh osteochondral allografting was successful in 77% of these relatively young patients and resulted in significant improvement in function and pain with high patient satisfaction, leading us to consider osteochondral allografting as a reasonable salvage option for patients with avascular necrosis of the knee joint.

Treatment options also remain limited in younger, active individuals with impeding knee arthrosis. The authors44 reported the results of osteochondral allografting in 37 knees with multifocal chondral lesions and arthritic changes. All patients demonstrated radiographic evidence of arthrosis. Assessment was performed with the modified D’Aubigne and Postel (18-point) scale and International Knee Documentations Committee (IKDC) score. Radiographs were evaluated by modified Fairbanks/Ahlbäck criteria. Again, subjective outcome measures included a patient questionnaire evaluating pain, function, and satisfaction. The 37 patients (25 males, 12 females) had a mean age of 42 years (range, 15–67 yr) and an activity level not ideally suited for arthroplasty. The mean follow-up was 36 months (range, 24–84 mo). Three patients were lost to follow-up. Nineteen of the allografts were unipolar, 10 involved bipolar/kissing lesions, and 5 multiple surfaces. The mean allograft area was 10.5 cm2. Twenty-six of 34 (76%) were considered successful (score, ≥15 points) and 8 (24%) were unsuccessful (3 converted to total knee arthroplasty, 2 underwent repeat allografting, 3 declined further surgery but were considered failures owing to fair/poor postoperative scores). The average 18-point scores improved from 11.5 points to 16.2 points, whereas IKDC scores improved from 33.0 points to 64.7 points (P < .01).

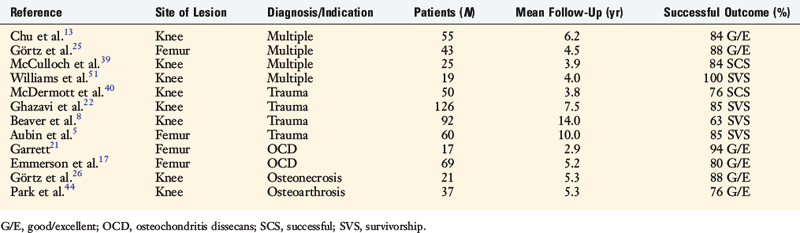

CLINICAL OUTCOMES FROM OTHER AUTHORS

Autografts

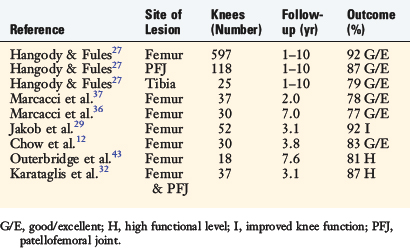

Hangody and Fules27 reported their 10-year clinical experience with autologous osteochondral mosaicplasty (Table 36-2). These investigators performed 831 mosaicplasties, involving 597 femoral condyles, 118 patellofemoral (patella and/or trochlea) joints, 76 talar domes, 25 tibial condyles, 6 capitulum humeri, 6 femoral heads, and 3 humeral heads. Concomitant surgery (ACL reconstruction, realignment procedures, and meniscal surgeries) was performed in 85% of the patients. Good to excellent results were reported in 92% of the patients who had femoral condyle grafts, 87% of those who had tibial grafts, and 79% of those who had patella grafts. Long-term donor-site morbidity was found in 3% of the patients.

Marcacci and coworkers37 reported on 37 athletes younger than 50 years of age with at least a 2-year follow-up. In this study, 23 of 37 patients (62%) underwent an associated procedure with arthroscopic mosaicplasty of the femoral condyle. The data revealed that 78% of the patients had good to excellent results. Twenty-seven patients returned to sports at the same level, 5 patients returned at a lower level, and 5 were unable to return to sports. Medial femoral condyle lesions statistically did not fare as well as lateral condyle lesions. Donor-site morbidity was not an identifiable problem in this case series.

The same group prospectively evaluated 30 patients with full-thickness chondral lesions (<2.5 cm2) of the knee treated with arthroscopic autologous osteochondral transplantation.36 The ICRS objective evaluation showed 76.7% of patients had good or excellent results at 7-year follow-up, and IKDC subjective score significantly improved from preoperative (34.8 points) to 7-year follow-up (71.8 points). The Tegner score showed a significant improvement after the surgery at 2- and 7-year follow-up (from 2.9 points to 6.2 and 5.6 points, respectively); however, sports participation declined from 2- to 7-year follow-up. MRI evaluation showed good integration of the graft in the host bone and complete maintenance of the grafted cartilage in more than 60% of cases.

In a study by Jakob and associates,29 92% of patients (48 of 52) demonstrated improved knee function at the latest follow-up (average, 37 mo) from open knee mosaicplasty. In 30 of 52 patients (58%), a concomitant procedure was performed. Four patients required reoperation because of graft failure.

With a mean follow-up of 45.1 months, Chow and colleagues12 reported on 30 patients who had undergone arthroscopic autologous osteochondral transplantation to the femoral condyle. Good to excellent results were reported in 83% (25 of 30) of patients. Lysholm scores increased from an average of 43.6 points preoperatively to a mean of 87.5 points postoperatively. Two patients (7%) had poor results and later underwent total knee arthroplasty.

Outerbridge and coworkers43 followed 18 knees for an average of 7.6 years after osteochondral autografting of the femoral condyle using the ipsilateral lateral patellar facet as the donor graft. These investigators reported an increase in Cincinnati knee scores from an average preoperative score of 37 points to an average final follow-up score of 85 points. Eighty-one percent (13 of 16) of the patients returned to a high functional level. Twelve percent (2 of 16) experienced moderate patellofemoral joint symptoms. Nevertheless, all patients were satisfied with the procedure results and, given the choice, would have the same surgery done again for an identical lesion on the contralateral knee.

Karataglis and associates32 reported on their mid- and long-term functional outcomes of 36 patients (37 knees) who underwent the osteochondral autograft transplantation technique with an average follow-up of 36.9 months. The lesions were located on the femoral condyle in 26 cases, on the trochlea in 7 cases, and on the patella in 4 cases. Thirty-two out of 37 patients (86.5%) reported significant improvement of their preoperative symptoms. All but 5 patients returned to previous daily and work activities. Eighteen patients returned to sports. Nine patients required second-look arthroscopies because of swelling, pain, or clicking. In 2 of those cases, the grafts were found to be loose and required revision. Symptoms improved significantly in 4 out of those 9 patients after repeat arthroscopy. Donor-site morbidity was not seen in this series.

Allografts

Garrett21 reported on the experience with fresh osteochondral allografts used as both a press-fit plug and a large shell graft in the treatment of 17 patients with OCD, all of whom had undergone previous surgery (Table 36-3). Sixteen patients (94%) reported relief of symptoms at 2- to 9-year follow-up. This work is remarkable for the first reported use of dowel grafts in the literature.

Chu and colleagues13 reported on 55 consecutive knees undergoing osteochondral allografting for diagnoses such as traumatic chondral injury, avascular necrosis, OCD, and patellofemoral disease. The mean age was 35.6 years, with follow-up averaging 75 months (range, 11–147 mo). Of the 55 knees, 43 were unipolar replacements and 12 were bipolar resurfacing replacements. On the 18-point scale, 45 of 55 of these knees (76%) were rated good to excellent, and 3 as fair. Of note, 36 of the 43 knees (84%) that underwent unipolar femoral grafts were rated good to excellent compared with only 6 of the 12 knees (50%) with bipolar grafts.

McDermott and coworkers40 reported on 100 patients treated with fresh osteochondral grafts implanted within 24 hours of recovery. Fifty patients had a unifocal traumatic defect of the tibial plateau or femoral condyle, 38 of which (76%) were considered successful at an average follow-up of 3.8 years. Patients with osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis had poorer results.

Ghazavi and associates22 reported on 126 knees in 123 patients with an average follow-up of 7.5 years. One hundred and five of 123 patients (85%) were rated as successful, and the remaining 18 failed. Advanced age (>50 yr), bipolar defects, malalignment, and Workers’ Compensation cases were considered main factors related to failure.

Beaver and colleagues8 performed a survivorship study on 92 knees allografted for post-traumatic cartilage lesions with failure defined as the need for a revision operation or the persistence of symptoms. There was a 75% success rate at 5 years, 64% at 10 years, and 63% at 14 years. Advanced age (>60 yr) and bipolar defects were again identified as factors for failure.

Aubin and coworkers5 later followed 60 patients, 41 of whom (68%) had undergone simultaneous realignment osteotomy and 10 (15%) concomitant meniscal transplantation. Kaplan-Meier survivorship analysis showed 51 grafts (85%) survived at 10 years and 44 (74%) at 15 years.

McCulloch and associates39 presented the results of 25 consecutive patients who underwent prolonged fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation for defects in the femoral condyle. The average patient age was 35 years (range, 17–49 yr). The average length of follow-up was 35 months (range, 24–67 mo). Statistically significant improvements (P < .05) were reported for the Lysholm (39 points to 67 points), IKDC scores (29 points to 58 points), all five components of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and the Short Form-12 physical component score (36 points to 40 points). Overall, patients reported 84% satisfaction (range, 25%–100%) with their results and believed that the knee functioned at 79% of their unaffected knee (range, 35%–100%). Radiographically, 22 of the grafts (88%) were incorporated into host bone.

Williams and colleagues51 prospectively followed 19 patients with symptomatic chondral and osteochondral lesions of the knee who were treated with fresh osteochondral allografts, with a mean preimplantation storage time of 30 days (range, 17–42 days). The mean age at the time of surgery was 34 years. The mean lesion size was 602 mm2. MRI was used to evaluate the morphologic characteristics of the implanted grafts. The mean duration of clinical follow-up was 48 months (range, 21–68 mo). The mean score (and standard deviation) on the Activities of Daily Living Scale increased from a baseline of 56 ± 24 points to 70 ± 22 points at the time of the final follow-up (P < .05). The mean Short Form-36 (SF-36) score increased from a baseline of 51 ± 23 points to 66 ± 24 points at the time of final follow-up (P < .005). At a mean follow-up interval of 25 months, cartilage-sensitive MRI demonstrated that the normal articular cartilage thickness was preserved in 18 implanted grafts, and allograft cartilage signal properties were isointense relative to normal articular cartilage in 8 of the 18 grafts. Osseous trabecular incorporation of the allograft was complete or partial in 14 patients and poor in 4 patients. Complete or partial trabecular incorporation positively correlated with SF-36 scores at the time of follow-up (R = 0.487; P < .05).

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Judy Blake for her assistance in preparation of this chapter.

1 http://www.cartilage.org/_files/contentmanagement/ICRS_evaluation.pdf. accessed October 1, 2007

2 Ahmad C.S., Cohen Z.A., Levine W.N., et al. Biomechanical and topographic considerations for autologous osteochondral grafting in the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:201-206.

3 Alford J.W., Cole B.J. Cartilage restoration, part 1: basic science, historical perspective, patient evaluation, and treatment options. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:295-306.

4 Allen R.T., Robertson C.M., Pennock A.T., et al. Analysis of stored osteochondral allografts at the time of surgical implantation. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1479-1484.

5 Aubin P.P., Cheah H.K., Davis A.M., Gross A.E. Long-term follow-up of fresh femoral osteochondral allografts for posttraumatic knee defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;391(suppl):S318-S327.

6 Ball S.T., Amiel D., Williams S.K., et al. The effects of storage on fresh human osteochondral allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:246-252.

7 Bartz R.L., Kamaric E., Noble P.C., et al. Topographic matching of selected donor and recipient sites for osteochondral autografting of the articular surface of the femoral condyles. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:207-212.

8 Beaver R.J., Mahomed M., Backstein D., et al. Fresh osteochondral allografts for post-traumatic defects in the knee. A survivorship analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:105-110.

9 Bobic V. [Autologous osteo-chondral grafts in the management of articular cartilage lesions]. Orthopade. 1999;28:19-25.

10 Buckwalter J.A. Articular cartilage. Instr Course Lect. 1983;32:349-370.

11 Burchardt H. The biology of bone graft repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;174:28-42.

12 Chow J.C., Hantes M.E., Houle J.B., Zalavras C.G. Arthroscopic autogenous osteochondral transplantation for treating knee cartilage defects: a 2- to 5-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:681-690.

13 Chu C.R., Convery F.R., Akeson W.H., et al. Articular cartilage transplantation. Clinical results in the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;360:159-168.

14 Convery F.R., Akeson W.H., Amiel D., et al. Long-term survival of chondrocytes in an osteochondral articular cartilage allograft. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1082-1088.

15 Czitrom A.A., Keating S., Gross A.E. The viability of articular cartilage in fresh osteochondral allografts after clinical transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:574-581.

16 Czitrom A.A., Langer F., McKee N., Gross A.E. Bone and cartilage allotransplantation. A review of 14 years of research and clinical studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;208:141-145.

17 Emmerson B.C., Gortz S., Jamali A.A., et al. Fresh osteochondral allografting in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyle. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:907-914.

18 Enneking W.F., Campanacci D.A. Retrieved human allografts: a clinicopathological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:971-986.

19 Fonseca F., Balaco I. Fixation with autogenous osteochondral grafts for the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (stages III and IV). Int Orthop. 2007;33:139-144.

20 Garretson R.B.3rd, Katolik L.I., Verma N., et al. Contact pressure at osteochondral donor sites in the patellofemoral joint. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:967-974.

21 Garrett J.C. Treatment of osteochondral defects of the distal femur with fresh osteochondral allografts: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:222-226.

22 Ghazavi M.T., Pritzker K.P., Davis A.M., Gross A.E. Fresh osteochondral allografts for post-traumatic osteochondral defects of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:1008-1013.

23 Görtz S., Bugbee W.D. Allografts in articular cartilage repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1374-1384.

24 Görtz S., Bugbee W.D. Fresh osteochondral allografts: graft processing and clinical applications. J Knee Surg. 2006;19:231-240.

25 Görtz S., Ho A., Bugbee W. Fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation for cartilage lesions in the knee. Trans Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;73:151.

26 Görtz S., Khadavi B., Jamali A., Bugbee W. Fresh osteochondral allografting for steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral condyles. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(suppl 1):S3-23.

27 Hangody L., Fules P. Autologous osteochondral mosaicplasty for the treatment of full-thickness defects of weight-bearing joints: ten years of experimental and clinical experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(suppl 2):25-32.

28 Highgenboten C.L., Jackson A., Trudelle-Jackson E., Meske N.B. Cross-validation of height and gender estimations of femoral condyle width in osteochondral allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;298:246-249.

29 Jakob R.P., Franz T., Gautier E., Mainil-Varlet P. Autologous osteochondral grafting in the knee: indication, results, and reflections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;401:170-184.

30 Jamali A.A., Hatcher S.L., You Z. Donor cell survival in a fresh osteochondral allograft at twenty-nine years. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:166-169.

31 Kandel R.A., Gross A.E., Ganel A., et al. Histopathology of failed osteoarticular shell allografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;197:103-110.

32 Karataglis D., Green M.A., Learmonth D.J. Autologous osteochondral transplantation for the treatment of chondral defects of the knee. Knee. 2006;13:32-35.

33 Koh J.L., Kowalski A., Lautenschlager E. The effect of angled osteochondral grafting on contact pressure: a biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:116-119.

34 Koh J.L., Wirsing K., Lautenschlager E., Zhang L.O. The effect of graft height mismatch on contact pressure following osteochondral grafting: a biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:317-320.

35 Mankin H.J. The response of articular cartilage to mechanical injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:460-466.

36 Marcacci M., Kon E., Delcogliano M., et al. Arthroscopic autologous osteochondral grafting for cartilage defects of the knee: prospective study results at a minimum 7-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:2014-2021.

37 Marcacci M., Kon E., Zaffagnini S., et al. Multiple osteochondral arthroscopic grafting (mosaicplasty) for cartilage defects of the knee: prospective study results at 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:462-470.

38 Maury A.C., Safir O., Heras F.L., et al. Twenty-five-year chondrocyte viability in fresh osteochondral allograft. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:159-165.

39 McCulloch P.C., Kang R.W., Sobhy M.H., et al. Prospective evaluation of prolonged fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation of the femoral condyle: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:411-420.

40 McDermott A.G., Langer F., Pritzker K.P., Gross A.E. Fresh small-fragment osteochondral allografts. Long-term follow-up study on first 100 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;197:96-102.

41 Miniaci A., Tytherleigh-Strong G. Fixation of unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the knee using arthroscopic autogenous osteochondral grafting (mosaicplasty). Arthroscopy. 2007;23:845-851.

42 Nakagawa Y., Suzuki T., Kuroki H., et al. The effect of surface incongruity of grafted plugs in osteochondral grafting: a report of five cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:591-596.

43 Outerbridge H.K., Outerbridge R.E., Smith D.E. Osteochondral defects in the knee. A treatment using lateral patella autografts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;377:145-151.

44 Park D., Chung C., Bugbee W. Fresh osteochondral allografts for younger, active individuals with osteoarthrosis of the knee. Trans Int Cart Rep Soc. 2006;5:10.

45 Pennock A.T., Wagner F., Robertson C.M., et al. Prolonged storage of osteochondral allografts: does the addition of fetal bovine serum improve chondrocyte viability? J Knee Surg. 2006;19:265-272.

46 Potter H.G., Foo L.F. Magnetic resonance imaging of articular cartilage: trauma, degeneration, and repair. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:661-677.

47 Robertson C.M., Allen R.T., Pennock A.T., et al. Up-regulation of apoptotic and matrix-related gene expression during fresh osteochondral allograft storage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:260-266.

48 Thaunat M., Couchon S., Lunn J., et al. Cartilage thickness matching of selected donor and recipient sites for osteochondral autografting of the medial femoral condyle. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:381-386.

49 Vangsness C.T.Jr., Garcia I.A., Mills C.R., et al. Allograft transplantation in the knee: tissue regulation, procurement, processing, and sterilization. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:474-481.

50 Williams R.J.3rd, Dreese J.C., Chen C.T. Chondrocyte survival and material properties of hypothermically stored cartilage: an evaluation of tissue used for osteochondral allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:132-139.

51 Williams R.J.3rd, Ranawat A.S., Potter H.G., et al. Fresh stored allografts for the treatment of osteochondral defects of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:718-726.

52 Williams S.K., et al. Analysis of cartilage tissue on a cellular level in fresh osteochondral allograft retrievals. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:2022-2032.

53 Williams S.K., Amiel D., Ball S.T., et al. Prolonged storage effects on the articular cartilage of fresh human osteochondral allografts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2111-2120.