13 Osteoarthritis and Inflammatory Arthritides of the Aging Spine

Because of space limitations, osteoarthritis of the aging spine will be primarily considered in this review. Certain inflammatory arthritides will be considered as a part of the differential diagnosis. Osteoarthritis is an almost ubiquitous disease and a significant source of morbidity. Although it can affect every age demographic, it has an increasing prevalence in the elderly population.1 In the elderly, osteoarthritis is a significant source of disability and has a deleterious effect on a patient’s quality of life. Although a majority of studies have examined the effect of osteoarthritis on hip, knee, and hand joints, osteoarthritis can affect any joint in the body, including those in the spine. Spinal osteoarthritis commonly manifests with back or neck pain. The degeneration caused by spinal osteoarthritis can also result in central canal or neural foraminal stenosis, or both, which may cause neurological deficit, including radiculopathy, neurogenic claudication, or myelopathy.

Clinical Case Examples

Clinical Case #1 (Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis)

Figure 13-1 presents lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 67-year-old woman with a 30-year history of progressive lower back pain. This pain was exacerbated by activity and relieved by rest. She reported no associated radicular symptoms. Past medical history was significant for morbid obesity, diabetes, and osteoarthritis. Physical exam did not reveal a neurological deficit. The patient had failed to improve despite intensive conservative therapy which included high dosage opiates, physiotherapy, epidural steroid injections, and facet blocks. MRI and plain radiography (see Fig. 13-4) revealed degenerative spondylolisthesis, central canal stenosis, and bilateral synovial cysts. Lateral flexion and extension films demonstrated a 10-mm anterolisthesis of L4 on L5 with 9 mm in extension and 11 mm in flexion. Due to increasing disability and lack of response to conservative measures, the patient was referred for evaluation for surgical intervention.

Clinical Case #2 (Degenerative Cervical Spondylosis)

Figure 13-2 presents axial computed tomography (CT) myelogram images of a 79-year-old woman with moderate neck pain and progressive difficulty with ambulating during the past 4 years. At presentation, the patient was wheelchair bound with limited ability to transfer. Past medical history was significant for osteoarthritis, atrial fibrillation, and multiple peripheral neuropathies. Physical examination revealed gross lower extremity hyperreflexia and weakness and was consistent with myelopathy. Her sensation was diffusely diminished in her hands and arms, but she did have normal sensation in the C4-C5 distribution. She did not have a Hoffman sign, but had extensive hand intrinsic muscle atrophy. She did have crossed adductor reflexes. She was able to flex and extend her neck to 35 degrees and laterally rotate to 40 degrees. The patient’s CT myelogram demonstrated severe spinal cord compression at the C4-C5, C5-C6, and C6-C7 levels. There was anterolisthesis and osteophytic bulging, which resulted in severe spinal canal narrowing.

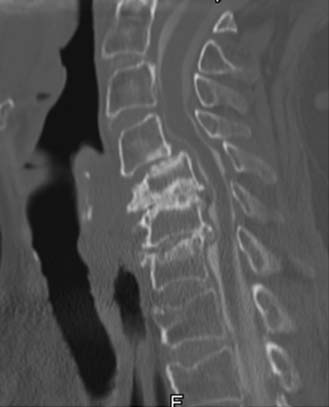

Clinical Case #3 (Atlantoaxial Instability)

Figure 13-3 presents images from a CT scan of an 85-year-old woman with severe neck pain and occipital neuralgia. The pain had been progressively worsening during the past 12-month period despite analgesia. Past medical history included hypertension, hypothyroidism, and osteoarthritis resulting in bilateral knee arthroplasties. On physical exam no weakness or evidence of myelopathy was detected. Dynamic imaging revealed a C1-C2 atlantodens interval of 4 mm in neutral, increasing to 5 mm in flexion and in extension. CT imaging (see Figure 13-3) demonstrated gross evidence of atlantoaxial instability including pannus. The patient received temporary relief with a greater occipital nerve block. Because of the overwhelming disability attributable to her neck pain and occipital neuralgia, the patient was considered for surgical intervention.

Basic Science

Osteoarthritis is a complex disease and may represent a series of diseases rather than one specific disease entity.1 The consensus definition states that osteoarthritis is a result of both mechanical and biological events that destabilize the normal coupling of degradation and synthesis of articular cartilage, extracellular matrix, and subchondral bone. When clinically evident, osteoarthritis is characterized by joint pain, tenderness, limitation of movement, crepitus, and variable degrees of inflammation without systemic effects.1 Osteoarthritis affects articular joints including the knees and hips. The zygapophyseal or facet joints are the synovial joints in the spine and therefore susceptible to osteoarthritis. Spinal osteoarthritis is therefore a disease of the facet joints due to degeneration, resulting in facet joint incompetence.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Spinal osteoarthritis has been demonstrated through radiographic and cadaver studies to affect every adult age group.2,3 The prevalence of clinical spinal osteoarthritis increases with age, with elderly patients having the highest radiographic and symptomatic prevalence.1,3 There is also a significant gender difference in prevalence. Females are more likely than males to suffer from osteoarthritis in general. The gender difference is exacerbated after menopause and therefore greater in the elderly.1

Other risk factors besides age and gender have been reported to be associated with the development of osteoarthritis. Obesity has a strong correlation with developing osteoarthritis. This likely represents added mechanical stress to the facet joints. Previous trauma from sports activities and occupations requiring strenuous physical labor have also been associated with the development of spinal osteoarthritis.1

Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis is a disease of the articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone. Although the exact etiology of osteoarthritis is not known, one theory is that cartilage matrix turnover is negatively affected by degenerative forces. This disrupts the balance between cartilage synthesis and degradation. Evidence suggests that collagenase, gelatinase, and stromelysin, which are enzymes involved in cartilage degradation, are increased in osteoarthritic joints.1 The cause for this imbalance is not clear. One proposed theory is that changes to the subchondral bone instigate changes to the cartilage matrix. Radiographic evidence of subchondral bone changes is often present in patients with osteoarthritis. It is theorized that stiffening of the subchondral bone due to microtrauma results in an abnormal environment for the overlying cartilage. This increases cartilage turnover and leads to further degradation of the joint. However, the debate as to whether subchondral bone changes are a result or cause of cartilage degeneration is not settled.1

Also unsettled is the role of the inflammatory response in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Localized inflammation has been demonstrated in certain stages of osteoarthritis, including mononuclear cell infiltrate and synovial hyperplasia. The exact role of this inflammation, be it causative or reactionary, is not clear. Markers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP) may be elevated as well.1 However, in general, systemic inflammation is not characteristic of osteoarthritis. Its presence would indicate that another pathology such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout should be considered.

Degenerative Mechanics

Osteoarthritic changes at the facet joints can have a cascading effect on a patient’s overall spinal health. The facet joints function as the posterolateral articulation between vertebral segments. As such, they bear weight, restrict anterior and posterior movement of the anterior column, and restrict axial rotation. Arthritic changes in these joints can promote abnormal spine mechanics, increasing degeneration. It is commonly held that facet joint arthrosis is a sequela of disc degeneration.4 However, there is evidence to suggest that facet arthrosis is a long-standing phenomenon present before evidence of disc degeneration.2 Either way, the coupling of facet joint arthritis with disc degeneration can lead to progressive degenerative changes. In the normal spine, facet joints bear between 18% and 25% of the segmental weight load.4,5 Facet joints in degenerative spines can bear upwards of 47% or more in extension.5 This leads to progressive stress on a weakened joint. Sequelae of continued stress on the weakened facet joint include osteophytosis and synovial cyst formation. These can cause radiculopathies if affecting the lumbar or cervical foramina. Specific symptoms vary by levels, with L4-L5 being the most commonly affected.5 Large osteophytes or synovial cysts coupled with anterior osteophytic change can lead to central canal stenosis. This stenosis can result in symptoms of neurogenic claudication when located in the lumbar spine, or symptoms of myelopathy when located in the cervical spine.

The atlantoaxial junction is a common site for arthritic changes, most commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis. Although classically not associated with osteoarthritis, atlantoaxial osteoarthritis has been reported to have a prevalence ranging between 5% and 18% of patients with spinal osteoarthritis.6 True symptomatic prevalence is probably much smaller. Arthritic changes can affect the lateral mass articulations and the atlantodens articulation. Degeneration at the atlantodens articulation can produce a pannus, similar to that seen in rheumatoid arthritis, causing myelopathic symptoms due to cord compression. More commonly, osteoarthritis at the atlantoaxial junction results in neck pain. This pain generally originates in the suboccipital region. It can radiate both cranially and caudally and can present with severe occipital pain. In general, occipital pain or subaxial neck pain without a suboccipital component most likely does not represent pain from atlantoaxial osteoarthritis, and other sources of pain should be excluded. In cases where the pain generator is difficult to locate based upon symptomatology, C1-C2 facet blocks can be a diagnostic aid if they relieve the neck pain.

Natural History

The natural history of spinal osteoarthritis is difficult to define. Most patients will present with back or neck pain, the etiology of which can be hard to determine. Some investigators feel that facet joints are a significant pain generator. Facet joints are innervated by branches of the dorsal rami of the same level and, the level above. After the capsule of the facet joint is innervated with nociceptive fibers. However, studies using facet blocks to examine facet joint contribution to spinal pain report varying prevalence from 7% to 75%.5 In addition, a large study of the prevalence of spinal osteoarthritis in women demonstrated a peak in incidence of osteoarthritis in the mid thoracic spine region. However, this radiographic peak did not correlate with any clinical symptoms. The same study did demonstrate a peak at the L4-L5 segment, which correlated with increased symptom scores.3 This study underlines the variability of clinical symptoms with significant radiographic findings.

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Evaluation

Rheumatological consultation may be necessary to exclude other inflammatory disorders. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) has a high prevalence in the elderly. It commonly manifests with calcification and ossification of soft tissues including ligaments and affects the spine. Symptoms usually involve pain and stiffness. Although it may be present concomitantly with osteoarthritis, DISH is usually radiographically distinct and recognizable by osteophytic change, often affecting the anterior longitudinal ligament, with preservation of the disc space. Rheumatoid arthritis can also cause signs and symptoms similar to osteoarthritis. Cervical degeneration with pannus formation is seen with advanced rheumatoid arthritis.

Exclusion of other pain generators is imperative. Radiographic evidence of arthrosis does not necessarily correlate with symptoms. Patients with significant back and hip pain should be evaluated for such conditions as trochanteric bursitis. Treatment via steroid injection may alleviate both hip and back pain. Evaluation of hip osteoarthritis should also be undertaken. A hip–spine syndrome has been postulated for several years as a cause of spine pain in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis. Recent evidence has suggested significant improvement in back pain scores and improvement in Oswestry disability scores in patients undergoing hip replacements for hip osteoarthritis.7 Because osteoarthritis commonly affects multiple joints, evaluation of the hip should be performed in patients with lower back and hip pain.

Conservative Therapy

Conservative therapy of spinal osteoarthritis is generally symptomatic. Recent evidence has suggested that alendronate and other bisphosphonates may have a role in disease modification. Alendronate can reduce osteophyte progression and disc space narrowing in patients with spinal osteoarthritis. In a randomly selected subgroup of the Fracture Intervention Trial, which examined the effectiveness of alendronate, patients receiving alendronate demonstrated a significantly reduced increase in osteophyte progression and disc space narrowing from T4 to L5.8 However, this was a secondary analysis and not a primary endpoint of the main study. After the results suggest that alendronate as a modifier of spinal osteoarthritis progression should be given further consideration.

Operative Therapy

The surgical treatment of painful spinal osteoarthritis remains controversial. No large-scale randomized trials exist to support intervention for neck or back pain or even mild neurological deficit.9,10 Evaluation for surgery should be tailored for each individual patient. Those patients with progressive neurological deficits or those who have failed extensive conservative therapies would seem to be better candidates for intervention. The type of intervention offered should be customized, because the goals of surgery will be different for each patient.

Neurological Decompression

Decompressive surgery may be indicated when the goal of surgery is to halt the progression of neurological deficit in patients with spinal osteoarthritis. Decompression of the central canal can alleviate symptoms of neurogenic claudication. Foraminotomies can reduce radicular pain. However, studies to date on lumbar and cervical decompression have not proved any significant benefit versus conservative therapy.9,10 Most studies are small, have poor outcome measures, and are retrospective. In the absence of significant supporting evidence, decompression may be indicated in cases of focal neurological element compromise, such as single level Foraminotomy. They may also be considered in patients who may not be good candidates for extensive procedures because of medical comorbidities. It should be stressed that decompressions have a poor track record in treating axial spinal pain.9,10

Instrumented Spinal Fusion

In recent years, the number of instrumented spinal fusion procedures has increased, despite a lack of evidence of their effectiveness at treating axial spinal pain and radicular pain.9,10 Conceptually, fusion procedures are attractive, because spinal osteoarthritis leads to facet joint instability. Those patients with axial spine pain demonstrably caused by facet arthrosis (i.e., improved with facet anesthetic blocks) may benefit from stabilization. However, there is no conclusive evidence to support this indication for fusion.9,10 Patients with extensive neurological compression may be candidates for instrumented fusion procedures. More extensive decompression can be performed without concern for posterior element instability. Patients with significant deformity due to osteoarthritic changes may also benefit from corrective procedures.

Atlantoaxial instability may be another indication for surgical intervention. Patients with intractable neck. occipital pain, or both that is attributable to C1-C2 instability may be good candidates for surgical intervention. Recent case series data suggest that C1-C2 fusion can effectively reduce pain by 65%.6 Atlantoaxial fusion would also be indicated in patients with significant pannus and myelopathy secondary to cord compression.

Minimally Invasive Alternatives

In elderly patients with multiple medical comorbidities, minimally invasive procedures hold great promise. Decreased blood loss and trauma are positives, whereas increased operative times and limited procedure offerings are potential negatives. The body of evidence regarding minimally invasive alternatives while comparatively small continues to grow. Recent evidence suggests that minimally invasive decompression may be safe and beneficial to elderly patients. In a group of 50 patients aged 75 and over, minimally invasive lumbar decompression was performed without major perioperative complication and with improvement in disability and pain, at least in the short term.11 This would suggest that minimally invasive decompressions may be an alternative for elderly patients not candidates for more traditional procedures.

Clinical Case Examples

Discuss Treatment, Clinical Challenges, and Future Treatments

Case #1

This patient had failed conservative therapy, but had multiple medical comorbidities. Despite this, operative intervention was felt to be of benefit as the patient’s current state of obesity and deconditioning prevented any further meaningful physiotherapy or exercise program. The patient was treated with decompressive laminectomies L3-L5 with complete L3-L4 and L4-L5 facetectomies. Bilateral placement of L3-L5 pedicle screws and right-sided L3-L4 and L4-L5 transforaminal interbody fusions were also performed. The fusion was supplemented with rhBMP-2 (recombinant human bone morphogenic protein 2) anterior to the interbody spacer which represents off-label use. Challenges with this patient included obesity and multiple medical comorbidities. Preoperative medical consultation was undertaken to identify and to minimize potential risks. Great care was taken in positioning the patient to prevent pressure-related complications. Postoperatively the patient obtained significant pain relief. Radiographs confirmed improved alignment (Figure 13-4).

Case #3

This 85-year-old patient was treated with posterior exposure of the upper cervical spine, C1 through C3 arthrodesis, including C1 lateral mass screws, right-sided C2 pedicle screw, and C3 lateral mass screws. C1-C3 arthrodesis was performed with a combination of rhBMP-2 and cancellous allograft bone. The fusion was extended to C3 because of concern for placing a left-sided C2 pedicle screw (Figure 13-5). Decompression was not performed because the patient did not demonstrate evidence of myelopathy. The patient tolerated the procedure well and had near complete resolution of neck pain 1 year post surgery.

1. Creamer P., Hochberg M.C. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):503-508.

2. Eubanks J.D., Lee M.J., Cassinelli E., et al. Does lumbar facet arthrosis precede disc degeneration? A postmortem study. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.. 2007;464:184-189.

3. Kramer P.A. Prevalence and distribution of spinal osteoarthritis in women. Spine. 2006;31(24):2843-2848.

4. Niosi C.A., Oxland T.R: Degenerative mechanics of the lumbar spine, Spine J., Suppl. 6:2004, 202S-208S.

5. Kalichman L., Hunter D.J. Lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis: a review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum.. 2007;37(2):69-80.

6. Schaeren S., Jeanneret B. Atlantoaxial osteoarthritis: case series and review of the literature. Eur. Spine J. 2005;14(5):501-506.

7. Ben-Galim P., Ben-Galim T., Nahshon R., et al. Hip Spine Syndrome: The effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine. 2007;32(19):2099-2102.

8. Neogi T., Nevitt M.C., Ensrud K.E. The effect of alendronate on progression of spinal osteophytes and disc space narrowing. Ann. Rheum. Dis.. 2008;67:1427-1430.

9. Fouyas I.P., Statham P.F., Sandercock P.A. Cochrane review on the role of surgery in cervical spondylotic radiculomyelopathy. Spine. 2002;27(7):736-747.

10. Gibson J.N., Waddell G. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis: updated Cochrane Review. Spine. 2005;30(20):2312-2320.

11. Rosen D.S., et al. Minimally invasive lumbar spinal decompression in the elderly: outcomes of 50 patients aged 75 years and older. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(3):503-509. discussion 509-510