Organization of the nervous system

The practice of clinical neurology depends on an appreciation of the structure and function of the nervous system. However, a detailed knowledge of neuroanatomy is not essential. This section will outline some of the important neuroanatomy needed for clinical neurology. Some areas, for example the anatomy of the visual system, will be described in the relevant section.

The levels of the nervous system

The nervous system is very complicated, in terms of both its structure and its physiology. Fortunately, when things go wrong they can be categorized on the basis of a relatively simple scheme of neuroanatomy. The nervous system can be thought of as having different levels (Fig. 1). The distribution and type of the clinical problem will often point to the affected level. For example, a patient who is confused must have a disturbance affecting the cerebral hemispheres. There are some situations when the level cannot immediately be determined: for example, a patient with foot drop could have a problem in the peripheral nerve, nerve root, spinal cord or cerebral hemisphere. Terminology used to describe disturbances at different levels is given in Box 1.

The central nervous system

The cerebral hemispheres

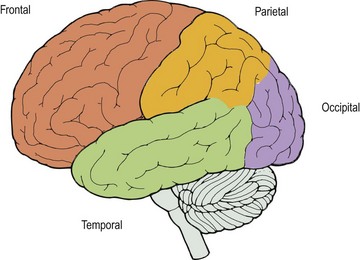

The cerebral hemispheres contain the apparatus of higher function. The dominant hemisphere (left in right-handed people) controls speech and the non-dominant hemisphere provides more spatial awareness. Different lobes undertake different functions (Fig. 2):

Frontal – motor control of the opposite side of the body, insight and control of emotions and, in the dominant hemisphere, output of speech.

Frontal – motor control of the opposite side of the body, insight and control of emotions and, in the dominant hemisphere, output of speech.Cerebellum

The cerebellum coordinates movement and is important in the control of balance and posture. The cerebellar hemispheres control coordination on the same side of the body. The central cerebellar structures are important in gait and sitting balance.

Brain stem

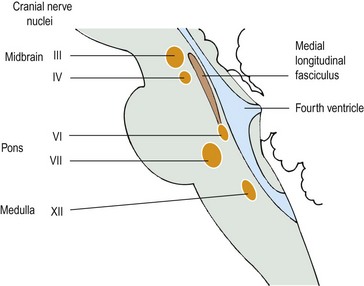

The brain stem contains nuclei, including the reticular formation, which maintains consciousness, and those for the cranial nerves (3–12), and the large white matter tracts running from the spinal cord to more central structures and vice versa. The descending motor tract, the corticospinal tract, mostly crosses over (decussates) in the pyramids in the medulla. The ascending dorsal column crosses in the medulla. The most useful nuclei for localization are the 3rd, 4th, 6th, 7th and 12th (Fig. 3). The fact that these tracts cross in the brain stem is helpful in localization of any lesion. A brain stem lesion can produce a cranial nerve lesion on one side and limb signs on the other side (e.g. a left-sided facial sensory loss and a right-sided sensory loss in the arm and leg in the lateral medullary syndrome).

The spinal cord

The spinal cord contains the sensory and motor tracts and within it are the anterior horn cells, the cell bodies of the motor neurones that run through the ventral root. These motor fibres in the ventral root join the dorsal root and leave the spinal canal. The sensory cell bodies lie outside the spinal cord, though within the spinal canal, in the dorsal root ganglion. The organization of the internal structure is helpful for localizing lesions and is described on pages 80–81.

The spinal cord is organized segmentally. This means that the nerves that arise in one segment innervate particular muscle groups (myotomes) and provide sensation for particular areas of skin (dermatomes). The dermatomes and myotomes are summarized on pages 23–25, 27 and 83. The spinal cord segments are referred to by the level at which the nerve root leaves the spinal canal. In the cervical spine these are numbered so that the root leaves the spinal canal above the vertebral body, except C8, which goes out below the 7th cervical vertebra and above the 1st thoracic vertebra. In the thoracic (T1 to T12), lumbar (L1 to L5) and sacral (S1 to S5) spine the segment goes out below the respective vertebra. However, the segments are not adjacent to the vertebral body as the spinal cord stops growing before the spinal column. This difference is most marked in the lumbar spine. In adults, the spinal cord ends (segmental level S5) at the level of the L1 vertebra.

The peripheral nervous system

Autonomic nervous system

Other levels of the nervous system

Not all types of neurological disorder fall into the system described above. One of the most difficult areas in clinical neurology is the diagnosis and management of patients with symptoms or signs that are not organically determined. These can be manifestations of overt psychiatric problems (e.g. the weakness and lethargy of a patient with depression) or they can be the sole manifestation of the psychiatric illness (e.g. a patient with a non-organic weakness or with non-epileptic seizures). These are discussed on pages 116–117.