CHAPTER 22 Oral Disease and Oral-Cutaneous Manifestations of Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease

DISORDERS OF THE MOUTH AND TONGUE

Xerostomia (dry mouth) is a common complaint with destruction or atrophy of the salivary glands as a result of autoimmune disease (Sjögren’s syndrome), after radiation therapy, or as a consequence of a variety of medications, such as anticholinergics, H1 antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, hypnotics, sedatives, antihypertensives, antipsychotics, antiparkinson agents, and diuretics.1

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease that is classified by the triad of xerostomia, keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes), and arthritis.2,3 It may be characterized as primary when no other disorders are diagnosed or secondary when connective tissue disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus, is present. The oral manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome are caused by the irreversible destruction of the salivary glands by a lymphocytic infiltrate that results in diminished or absent saliva. The lack of saliva is associated with difficulty chewing, odynophagia, and diminished taste and smell, as well as mucosal erythema, increased incidence of dental caries, oral candidiasis, and salivary gland calculi. Sucking mints and chewing gum may help by increasing salivary flow, which assists in the the removal of debris. Patients with xerostomia should avoid sweets and acidic foods and beverages and be encouraged to sip water and suck ice chips frequently. Preparations containing 1% sodium carboxymethyl cellulose may be used to moisten the oral cavity. Salivary stimulants such as cevimeline (Evoxac), 30 mg three times daily, or pilocarpine (Salagen), 5 mg four times daily, are effective sialogogues.

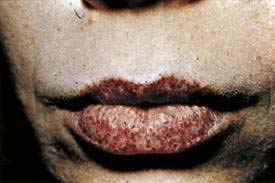

Glossitis, inflammation of the tongue, occurs in a heterogeneous group of disorders that includes nutritional deficiencies, chemical irritants, drug reactions, iron deficiency, pernicious anemia, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, infections, and vesiculoerosive diseases. Sometimes, no underlying cause can be detected.3 Patients may complain of lingual pain (glossodynia) or burning sensation (glossopyrosis). Loss of filiform papillae results in a spectrum of changes, from patchy erythema with or without erosive changes to a completely smooth, atrophic, erythematous surface (Fig. 22-1). Atrophic glossitis is a sign of protein-calorie malnutrition and muscle atrophy and is commonly found in older adults. Median rhomboid glossitis manifests as an asymptomatic, well-defined erythematous patch in the midposterior dorsum of the tongue.4

Glossodynia (burning sensation or pain in tongue) in the absence of clinical or histologic evidence of glossitis may be associated with anxiety or depression. Although it is found most commonly in postmenopausal women, hormonal therapy is of no value.5 Hypnosis has been found to improve glossodynia when a psychogenic component or when organic disease is present.6 Serologic evaluation for hypomagnesemia and for vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, as well as a complete medication history, may occasionally yield a correctable cause.7

Hypogeusia (diminished sense of taste) and dysgeusia (distortion of normal taste) are other complaints that are sometimes associated with glossitis. Hypogeusia and dysgeusia have been attributed to various neurologic, nutritional, and metabolic disorders and to a large number of medications. The evidence supporting these associations is tenuous.8,9 How taste buds are affected by aging is not understood. Tobacco smokers, denture wearers, and patients with anxiety or other psychiatric disorders commonly complain of hypogeusia and dysgeusia. Radiation therapy to the head and neck may result in altered taste. The therapy is empirical and includes identifying and correcting any associated condition. Patients may be treated with zinc supplementation, a low-dose anxiolytic, or an antidepressant medication such as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).10 Paradoxically, tricyclic antidepressant medications block responses to a wide range of taste stimuli and may contribute to clinical reports of hypogeusia and dysgeusia.11,12

Geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis) is characterized by patchy loss of filiform papillae forming irregular, moving configurations that resemble geographic landmarks on a map. Geographic tongue is reported to occur in up to 4% of the population. Patients may complain of pain or difficulty in eating acidic, spicy, or salty foods. Recurrent episodes are common and may represent pustular psoriasis. Some patients may present with an exfoliative cheilitis and/or migratory annular plaques and papules on any of the oral mucosal surfaces, representing geographic mucositis in ectopic locations. Histologically, spongiosus and neutrophilic microabscesses are found in the epithelium, with no evidence of candidiasis. Treatment consists of topical anesthetics, benzocaine (Orabase) or aluminium hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide (Maalox) protective coatings, and topical glucocorticoids, along with control of the underlying cutaneous psoriasis if present.13 Geographic tongue has no known associations with malignancy.14

Black hairy tongue is another common entity. The dorsal surface of the tongue may appear yellow, green, brown, or black because of exogenous pigment trapped within elongated keratin strands of filiform papillae.15 Acquired black hairy tongue is seen most commonly in chronic smokers and often follows a course of systemic antibiotics, the use of hydrogen peroxide, or drinking coffee or tea.14 Off-label treatment consists of 25% podophyllum or topical tretinoin (Retin-A) gel.15 Chronic débridement with a tongue scraper may also be helpful.

MUCOCUTANEOUS DISORDERS

CANDIDIASIS

Candida spp. (chiefly Candida albicans) are part of the normal flora in almost half of the population. Oral candidiasis or candidosis (moniliasis, thrush) typically appears as white curd-like patches or as red (atrophic) or white and red friable lesions on any mucosal surface (Fig. 22-2). Many newborns experience initial overgrowth of Candida before colonization of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Candidiasis often occurs during or after antibiotic or glucocorticoid therapy, in denture wearers, pregnant women, and older adults, and in patients with anemia, diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Cushing’s disease, or familial hypoparathyroidism. Immunosuppression caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; see later), other debilitating illnesses, or cancer chemotherapy may lead to candidiasis (see Chapter 33). Candida albicans remains the predominant species cultured. However, C. glabrata, C. krusei, and other azole-resistant species must be considered in resistant cases. Oral candidiasis is also associated with xerostomia, whatever the cause. Topical therapy is most effective in patients with no underlying chronic conditions (see Chapter 45) and may entail the use of the following: (1) nystatin (Mycostatin), 100,000-U vaginal tablet dissolved orally three to five times daily; (2) clotrimazole (Mycelex), 10-mg troche to be dissolved orally five times daily; or (3) clotrimazole, 500-mg vaginal tablet, to be dissolved orally at bedtime.

Topical agents are effective in the absence of immunosuppression, whereas oral antifungal agents are needed in immunocompromised patients (see Chapters 33 and 34). In denture wearers, adjunctive measures, including regular denture cleaning, soaking in a dilute bleach solution, and taking the dentures out overnight, are important for clearing. When dysphagia and/or upper GI bleeding accompany oral thrush, concurrent candidal esophagitis should be considered (see Chapter 45). Systemic candidiasis may result when normal barriers to infection are lost. Microthrombi, resulting from obstruction of cutaneous and systemic vessels, lead to local necrosis and manifest as small necrotic papules and ulcerations that are easily visible on the skin and mucosa.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION

Oral and cutaneous complications are common in patients with HIV infection (see Chapter 33).16 These manifestations cause significant morbidity and can provide valuable diagnostic and prognostic information. Frequently, the first and most common HIV-associated infection of the mouth is candidiasis. The history and physical findings usually establish the diagnosis. The presence of spores, pseudohyphae, or hyphal forms on a smear (potassium hydroxide, periodic acid–Schiff, Papanicolaou), culture, or biopsy confirms the diagnosis. Oral candidiasis in HIV should be treated systemically. Systemic therapy involves the use of oral azole preparations (fluconazole or itraconazole). Amphotericin B given intravenously is also effective, but usually not necessary. Treatment for one to two weeks is usually effective, even in the late stages of HIV infection. Frequent recurrences may require chronic or repeated treatment. The likelihood of clinical relapse is dependent on the degree of immunosuppression and the duration of therapy. As adjunctive measures, mouth rinses with chlorhexidine gluconate (Peridex), Listerine, or hydrogen peroxide–saline may be of some benefit.17,18

Hairy leukoplakia (oral hairy leukoplakia, HL) appears as corrugated white lesions on the lateral borders of the tongue (Fig. 22-3). HL is usually asymptomatic and may be an early sign of HIV infection. The epithelium in patients with HL is infected with Epstein-Barr virus.19 The severity of HL does not correlate with the stage of HIV disease. However, the presence of HL in an HIV-infected person has prognostic implication. Analysis of 198 cases of HL has demonstrated that the median time to onset of AIDS is 24 months, and the median time to death in the era prior to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was 41 months.20 Other mucosal white lesions, such as oral leukoplakia (Fig. 22-4), can resemble HL lesions; biopsy confirmation should be considered if the diagnosis of HL is in doubt. HL may be confused with candidiasis (which coexists in about half of cases). A prudent first step in management is the administration of anticandidal therapy. The suspicion of HL justifies a discussion of its implications and suggestion of HIV testing. Although HL occurs predominantly in HIV-infected homosexual and bisexual men, it also has been found in renal and other organ transplant recipients. Because HL is usually asymptomatic, treatment is elective. HL responds to oral acyclovir, topical retinoic acid, and podophyllum. When treatment is discontinued, HL usually returns.

Figure 22-3. Hairy leukoplakia involving the tongue in a patient with AIDS.

(Courtesy of Dr. Sol Silverman, Jr, DDS, and Dr. Victor Newcomer.)

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a common consequence of HIV infection and is associated with human herpesvirus 8. A significant decline in the incidence of KS occurred during 1996 and 1997, which corresponded to the introduction of HAART. Although KS is usually found on the skin, more than half of patients also have intraoral lesions.21 The first sign of KS occurred in the mouth in 22% of patients and, in another 45%, KS occurred in the mouth and skin simultaneously.20,21 The cutaneous lesions of KS appear as asymptomatic red to purple, oval macules that develop into papules, plaques, or nodules. They rarely ulcerate, except on the lower extremities and genitalia. Edema often accompanies cutaneous lesions, especially on the lower extremities or on the face. Oral lesions may vary in appearance from minimal, asymptomatic, flat, purple or red macules to large nodules. The hard palate is the most frequent location, followed by the gingiva and tongue (Fig. 22-5).22 The differential diagnosis of KS includes purpura, hemangioma, coagulation defects, and bacillary angiomatosis. Diagnosis is established by biopsy. Treatment approaches are mainly palliative but include topical alitretinoin (9–cis-retinoic acid) gel, imiquimod, radiation therapy, chemotherapy (including intralesional injections), and surgery.23 Patients with cutaneous KS may have asymptomatic visceral lesions (see Chapter 33).

Figure 22-5. Kaposi’s sarcoma involving the palate.

(Courtesy of Dr. Sol Silverman, Jr, DDS, and Dr. Victor Newcomer.)

Other conditions associated with HIV infection include the following: extensive oral, genital, or cutaneous warts; recurrent aphthae; chronic mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections; lymphocytic infiltrates of major salivary glands, leading to secondary Sjögren’s syndrome; drug reactions, including drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome; Bartonella infections (bacillary angiomatosis and its associated peliosis hepatis); premature and progressive periodontal disease; and acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis.24

ULCERATIVE DISEASES

Aphthous ulcers (canker sores, recurrent aphthous ulcers [RAUs]) are painful shallow ulcers, often covered with a grayish-white or yellow exudate and surrounded by an erythematous margin. They appear almost exclusively on unkeratinized oral mucosal surfaces (Table 22-1). Rarely, RAUs may occur in the esophagus, upper and lower GI tracts, and anorectal epithelium. RAUs develop at some time in 25% of individuals in the general population and recur at irregular intervals. Three clinical forms of aphthous ulcers are recognized—minor aphthae (most common), major aphthae (less common), and herpetiform aphthae (least common). Minor aphthae typically are smaller than 5 mm and heal in one to three weeks (Fig. 22-6A). Major aphthae may exceed 6 mm (see Fig. 22-6B) and require months to heal, often leaving scars. Herpetiform aphthae are 1 to 3 mm in diameter, occur in clusters of 10 to hundreds of ulcers, and resolve quickly.42

Table 22-1 Distinctions between Aphthous and Herpetic Oral Ulcers

| CONDITION | MUCOSA | LOCATION |

|---|---|---|

| Aphthous ulcers | Unkeratinized | Lateral tongue, floor of the mouth, labial and buccal mucosa, soft palate, pharynx |

| Herpes simplex virus ulcers | Keratinized | Gingiva, hard palate, dorsal tongue |

The cause of RAU is thought to be multifactorial, with precipitating factors including the following: (1) immunologic abnormalities such as celiac disease and increased allergen presentation caused by decreased constitutive oral barriers (putatively from sodium lauryl sulfate use in dental products); (2) chronic trauma, such as from ill-fitting dentures; (3) vitamin or mineral deficiencies, such as iron, folate, and vitamin B12; (4) genetic predisposition; (5) stress and anxiety; (6) allergies to food or medication, such as to cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors or sertraline; and (7) xerostomia.25 Helicobacter pylori infection may be associated with RAUs as eradication of H. pylori appears to be associated with a reduction of recurrences, as well as a decrease in the number of ulcers and days of symptoms.26 Morphologically identical aphthous lesions may be seen in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; see later) and Behçet’s syndrome. The workup for recurrent aphthous ulcers includes a complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum iron, ferritin, folate, and B12 levels, potassium hydroxide (KOH) stain, Tzanck smear, viral culture, biopsy of coexisting skin lesions to exclude HSV, and colonoscopy to address the possibility of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Histologically, lesional tissue shows ulcerated mucosa with chronic mixed inflammatory cells.

Management of aphthous ulcers includes palliative and curative measures. First, vitamin deficiencies, if found, should be treated. Otherwise, patients should be advised to use multivitamins with iron and avoid crusty, salty, or spicy foods to minimize irritation of oral lesions. Soft toothbrushes, repair of dentition, and other measures to avoid unnecessary oral trauma should be instituted. Analgesics and topical anesthetics such as 2% viscous lidocaine may be helpful, along with bismuth subsalicylate (Kaopectate) and sucralfate to protect lesions and accelerate healing. Aphthous ulcers can be treated effectively with a potent topical glucocorticoid, such as fluocinonide (Lidex) or clobetasol (Temovate) gel or ointment. Second-line therapy includes colchicine, 0.6 mg three times daily; cimetidine, 400 to 800 mg/day; azathioprine, 50 mg/day; or thalidomide, 200 mg/day (U.S. Food And Drug Administration [FDA]–approved for HIV patients). Short courses of systemic prednisone (20 to 60 mg/day) are reproducibly effective when more conservative approaches are not satisfactory. An elimination diet may be helpful for patients with allergic reactions to certain foods or medications, including a trial of sodium lauryl sulfate–free dental products.27 A gluten-free diet is recommended for patients with gluten-sensitive enteropathy (see Chapter 104).

Recurrent orolabial herpes simplex is caused by reactivation of HSV that has been dormant in regional ganglia, with no associated increase in HSV antibody titers. Episodes may be precipitated by fever, sunlight, and physical or emotional stress. Recurrences vary in frequency and severity. Typically, the lesions involve the lips (cold sores) and are preceded by several hours of prodromal symptoms such as burning sensation, tingling, or pruritus. Vesicles then appear but soon rupture, leaving small, irregular, painful ulcers. Coalescence of ulcers, crusting, and weeping of lesions are common. Intraoral recurrent herpetic ulcers occur on keratinized mucosa (i.e., hard palate or gingiva; see Table 22-1). They appear as shallow, irregular, small ulcerations and may coalesce. Labial and oral herpetic ulcers normally heal in less than two weeks. Recurrent HSV is the most common cause of recurrent erythema multiforme.

In immunocompromised patients, HSV can affect any mucocutaneous surface and can appear as large, irregular, pseudomembrane-covered ulcers. This is especially true in HIV-infected persons, in whom all perineal and orolabial ulcerations should be considered manifestations of HSV until proven otherwise (see Chapters 33 and 125). Care should be taken to avoid ocular autoinoculation.

Herpes simplex is usually diagnosed from the history and clinical findings. A history of a prodrome or of vesicles, the site of lesions, and the reappearance of lesions in the same location help differentiate herpes from other ulcerative disorders. A cytologic smear (Tzanck) showing multinucleate giant cells is suggestive, although viral cultures and monoclonal antibody staining of smears are more sensitive and specific tests for diagnosing HSV infection. Topical acyclovir is of little benefit in recurrent labial herpes and is of limited benefit in recurrent genital HSV. Systemic acyclovir is regularly used for treatment of primary or recurrent attacks in immunosuppressed patients (2 g orally in divided doses, or 5 mg/kg intravenously three times daily until lesions heal). Famciclovir, 125 mg twice daily, or valacyclovir, 500 mg twice daily, are also available in the United States. Oral treatment should optimally begin within the first few hours of the prodrome. Suppression of recurrences may be accomplished with acyclovir, 200 mg orally three times daily or 400 mg twice daily. Acyclovir is used for the prevention of recurrent oral and genital herpes associated with bone marrow transplantation (see Chapter 34). Antivirals are also used to prevent recurrent herpes infections in other immunocompromised patients such as those with leukemia or HIV infection, or after solid organ transplantation.

VESICULOBULLOUS DISEASES

Pemphigoid is a general term for heterogeneous blistering disorders characterized by bullae and ulcers affecting the mucosa of the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, anus, conjunctiva, and skin. Oral findings appear as highly inflamed (erythematous) mucosa on the buccal mucosa and gingival mucosa. Two types of pemphigoid have been identified, bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial (mucous membrane) pemphigoid. Patients with bullous pemphigoid typically have skin lesions, and about one third also have mucous membrane lesions. All patients with cicatricial pemphigoid have mucosal lesions, and about one third also have skin lesions (tense bullae). Ocular symblepharon (i.e., adhesion between the tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva) commonly occurs with cicatricial pemphigoid. Potentially fatal upper GI bleeds because of esophageal involvement by pemphigoid has been reported.28 Immunofluorescent staining of involved mucosa and skin shows linear deposition of antibody and complement in the basement membrane zone. Serum antibodies against 230- and 180-kd antigens located at the squamous epithelial basement membrane have been documented. Patients with serum IgG and IgA antibodies are more likely to respond to systemic medications. Treatment ranges from low-dose to high-dose prednisone for patients without contraindications to glucocorticoid use. Alternative therapies for patients with contraindications or systemic toxicities to glucocorticoids include dapsone, tetracycline and nicotinamide in combination, azathioprine, chlorambucil, plasma exchange, intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide given orally or in a pulse-dosing format, methotrexate, and infliximab.29

Paraneoplastic pemphigus shares features of pemphigus vulgaris and erythema multiforme.30 It is associated with various malignancies, including GI malignancies, lymphomas and leukemias, thymomas, and soft tissue sarcomas. Five features characterize paraneoplastic pemphigus: (1) painful mucosal erosions and a polymorphous skin eruption; (2) intraepidermal acantholysis, keratinocyte necrosis, and vacuolar interface reaction; (3) deposition of IgG and C3 intercellularly and along the epidermal basement membrane zone; (4) serum autoantibodies that bind to skin and mucosa epithelium in a pattern characteristic of pemphigus, as well as binding to simple, columnar, and transitional epithelia; and (5) immunoprecipitation of a complex of four proteins (250, 230, 210, and 190 kd) from keratinocytes by the autoantibodies. The prognosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus depends on the associated underlying malignancy, and successful treatment is predicated on successful elimination of the underlying malignancy.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a heterogeneous group of rare inherited disorders of skin fragility (Fig. 22-7). They are characterized by the formation of blisters with minimal trauma and are divided into dystrophic (scarring), junctional, and simplex forms. Oral erosions, premature caries, and gingival involvement, as well as GI disease, are common in the dystrophic form but also occur in some patients with the junctional form. In addition to oral erosions, esophageal strictures are the most common GI complication in dystrophic EB.31 They may be narrow or broad and most commonly occur in the upper third of the esophagus, but also may be found in the lower third. The esophageal strictures are probably induced by repeated trauma from food and/or refluxed gastric contents; therefore, strict adherence to a soft food diet remains a mainstay of management. Although dilations with bougienage historically have been shunned because of an unacceptable risk of increasing esophageal stenosis over the long term, evidence supports the use of balloon dilation as a safe and efficacious method of palliating esophageal strictures without this risk. Surgical excision, feeding gastrostomy, and colonic interpositioning have been effectively used in dystrophic EB patients with severe esophageal strictures. Esophageal webs in the postcricoid area have also been described. Anal stenosis and constipation (with or without stenosis) are frequent in patients with dystrophic EB. Junctional EB has been uniquely associated with pyloric atresia. Anemia and growth retardation frequently develop in patients with severe dystrophic and junctional EB, partly because of GI and oral complications.

Figure 22-7. Characteristic lesions resulting from skin fragility caused by epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica.

Patients with clinical lesions identical to the dystrophic forms of EB but with no family history and an adult onset have been identified; their condition is called acquired EB or EB acquisita (EBA). EBA, like pemphigus and pemphigoid, is an autoimmune disease. The autoantibodies in EBA are directed against type VII collagen.32 The diagnosis of EBA is established by routine histology and direct immunofluorescence examination of skin biopsy specimens. Patients may have significant mucosal involvement, like patients with cicatricial pemphigoid, especially oral and esophageal disease. Coexistent Crohn’s disease has been reported in a number of patients with EBA. Treatment is with immunosuppressive agents.

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute, benign mucocutaneous eruption associated with underlying infections (especially HSV). It is often preceded or accompanied by low-grade fever, malaise, and symptoms suggesting an upper respiratory tract infection. The eruption consists of alternating pink and red target lesions on the elbows, knees, palms, and soles and of shallow, broad oral erosions. Patients with EM may only have oral involvement. Variable degrees of nonspecific erythema are found, with or without ulcers. Crusting, hemorrhagic, and moist lip ulcers may be present. Severe oral and pharyngeal pain, secondary bacterial and fungal infections, and bleeding are common complications. The diagnosis is made by clinical characteristics, ruling out other specifically diagnosable diseases, and by response to treatment. The biopsy reveals a nonspecific interface reaction. Oral EM can be self-limited or chronic, and often the inciting process goes unidentified. Management includes palliative measures and elimination of any offending agent. Often, glucocorticoids and/or other immunosuppressive drugs are needed. Recurrences and flares have variable patterns. Herpes-associated erythema multiforme lesions are treated with episodic or suppressive antiviral therapy with acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir, or foscarnet.33

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (between 10% and 30% skin sloughing) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (more than 30% skin sloughing) are diagnosed when severe, acute targetoid lesions and skin sloughing occur in association with eye, skin, and mucous membrane involvement. Diffuse oral and pharyngeal ulceration may prevent oral intake. At endoscopy, the esophagus may show diffuse erythema, friability, and whitish plaques that can be mistaken for candidiasis. Diffuse gastric and duodenal erythema and friability may be present without esophageal involvement. The colonoscopic appearance may resemble severe ulcerative or pseudomembranous colitis. However, colonic biopsies show extensive necrosis and lymphocytic infiltration, without crypt abscesses or neutrophils. This pattern is reminiscent of graft-versus-host disease (see Chapter 34). The mucosa of large portions of bowel may slough in Stevens-Johnson syndrome, accounting for reports of hematemesis, melena, and intestinal perforation. Treatment largely consists of discontinuation of offending pharmaceutical agents (often anticonvulsants), hospital admission to a burn unit, and supportive care by a multiteam approach. Some evidence suggests that IVIG is beneficial when administered early in the course and that glucocorticoids actually have a negative effect on outcomes.34

LICHEN PLANUS

Lichen planus is a common, chronic inflammatory disorder involving the mucosa and skin. The disease usually begins in adulthood, and two thirds of patients are women. Oral lesions appear as white, lace-like and/or punctate patterns on any mucosal surface (Fig. 22-8). Mucosal erythema or ulceration is common. The lesions are small, flat-topped, pruritic, violaceous papules. Oral lesions can be asymptomatic or severe oral pain may develop. Topical and/or systemic glucocorticoids are effective in decreasing the signs and symptoms in almost all cases of oral and cutaneous lichen planus. In rare refractory cases, systemic retinoids are necessary. Topical tacrolimus is an effective steroid-sparing treatment alternative. Esophageal lichen planus may present with progressive dysphagia and odynophagia, upper GI bleeding, strictures and squamous cell carcinoma. The endoscopic findings include erythema, ulcers, proximal esophageal webs, and erosions throughout the esophagus. An increased prevalence of chronic liver disease, including chronic active hepatitis C and primary biliary cirrhosis, has been reported in patients with lichen planus. Oral lichen planus may be associated with an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma arising in areas of atrophy or erosion, regardless of treatment.35,36

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS OF INTESTINAL DISEASE

Both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis may be accompanied by cutaneous manifestations (see Chapters 111 and 112). Skin lesions are more common (up to 44%) and often more specific in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis. It is rare for cutaneous involvement by Crohn’s disease to appear before symptomatic bowel disease. The most common cutaneous complication of Crohn’s disease is granulomatous inflammation of the perianal or perifistular skin, which occurs by direct extension from underlying diseased bowel. Metastatic Crohn’s disease refers to rare ulcerative lesions, plaques, or nodules that occur at sites distant from the bowel. Such lesions favor intertriginous areas, such as the retroauricular and inframammary regions. On histologic study, local cutaneous extension and metastatic Crohn’s disease show sarcoid-like granulomatous inflammation, and both occur with greater frequency in patients with colonic involvement by Crohn’s disease.37

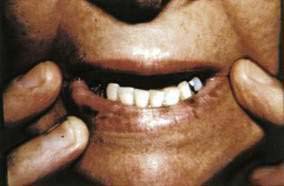

Oral manifestations of Crohn’s disease occur in 4% to 14% of patients and include aphthae (see Fig. 22-6), lip fissures, cobblestone plaques, cheilitis, mucosal tags, and perioral erythema. Patients may also complain of metallic dysgeusia. Aphthosis occurs in approximately 5% of patients with Crohn’s disease, and the lesions are indistinguishable, clinically and histologically, from typical aphthae. Aphthosis and perianal-perifistular ulcerations are not seen in ulcerative colitis. Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare condition with recurrent lip swelling that leads to enlargement and firmness of the lips. A biopsy shows noncaseating granulomas. In rare cases associated with Crohn’s disease,38 this condition may be a component of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (scrotal tongue, lip swelling, with or without facial palsy and migraine), or may be idiopathic.

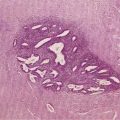

Pyostomatitis vegetans (Fig. 22-9), and its cutaneous counterpart, pyoderma vegetans, is characterized by pustules, erosions, and vegetations involving the labial mucosa of the upper and lower lips, buccal mucosa, and gingival mucosa, as well as the skin of the axillae, genitalia, trunk, and scalp. Both pyostomatitis vegetans and pyoderma vegetans are specific markers of IBD (Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis) and may precede the GI symptoms by months to years. Histologically, intraepithelial and subepithelial eosinophilic miliary abscesses are characteristic. Superficial pustules coat the friable, erythematous, and eroded mucosa of the oral cavity, least commonly the floor of the mouth and tongue. Symptoms may be severe or minimal. Eosinophilia and anemia are common. Diagnosis is made from biopsy findings, and treatment is with topical or systemic glucocorticoids, dapsone, or sulfasalazine.

Figure 22-9. Pyostomatitis vegetans in a patient with ulcerative colitis. A biopsy specimen revealed microabscesses.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a noninfectious ulcerative cutaneous disorder of unknown pathogenesis (Fig. 22-10). The classic lesion is a tender or painful ulcer with an elevated, dusky purple border that is widely undermined. One or multiple lesions may occur. Lesions begin as small papulopustules that break down very rapidly. Pathergy, the appearance of new ulcers at sites of minor trauma or surgery, is often present. The diagnosis is one of exclusion, in that infectious and other causes of ulceration, including factitia, must be ruled out. Most cases of pyoderma gangrenosum occur in patients with no underlying disease. Pyoderma gangrenosum develops in approximately 5% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 1% of patients with Crohn’s disease. The bowel disease may be subclinical when the skin lesions appear and therefore bowel evaluation, especially of the rectum and distal colon, is essential in cases of pyoderma gangrenosum. If the disorder is associated with underlying bowel disease, therapy of the bowel disease may lead to improvement of the skin lesions. The usual management of pyoderma gangrenosum includes local wound care, high-dose systemic glucocorticoids, or steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.37

VASCULAR AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISORDERS

Immune complex vasculitis of small vessels (leukocytoclastic vasculitis) appears on the skin of dependent sites as crops of palpable purpura and is mediated by deposition of immune complexes in postcapillary venules (Fig. 22-11; see Chapter 36). Although GI involvement can occur in any case of small vessel vasculitis, it occurs in 50% to 75% of patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (Fig. 22-12).39 Vasculitic hemorrhage, bowel wall edema, and intussusception affect the jejunum and ileum most commonly. Direct immunofluorescence of early skin lesions reveals deposits of IgG in most cases of small vessel vasculitis and deposits of IgA in Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease, Köhlmeier-Degos syndrome, progressive arterial mesenterial vascular occlusive disease, or disseminated intestinal and cutaneous thromboangiitis) is a rare multisystem vasculopathy disorder that is occasionally familial. Cutaneous lesions are the initial manifestations, appearing most commonly in early adulthood. They appear as crops of asymptomatic, pink, 2- to 5-mm papules that rapidly become umbilicated and develop a characteristic atrophic, depressed, porcelain white center (Fig. 22-13). These lesions represent cutaneous infarcts. Similar infarcts are seen in the small bowel in almost all cases. Although GI involvement may initially be asymptomatic or nonspecific, an acute abdominal catastrophe eventually occurs, often necessitating laparoscopy or laparotomy. Perforation of the intestine is usually found, along with multiple white, yellowish, or rose-colored flat or slightly depressed patches below an intact serosa, usually in the small intestine. The intestinal disease is recurrent and eventually is often fatal. Cerebral and peripheral nerve infarcts develop in approximately 20% of patients, leading to neurologic complications that can include hemiparesis, aphasia, cranial neuropathies, monoplegia, sensory disturbances, and seizures. Histologic study reveals that the infarctive lesions of the skin, gut, and nervous system are consequences of noninflammatory thromboses. The pathogenesis of Degos’ disease is unknown, but identical lesions have been reported in systemic lupus erythematosus and in a patient without systemic lupus erythematosus with anticardiolipin antibodies and a lupus anticoagulant. Treatment has been attempted with antithrombotic agents such as aspirin, ticlopidine, and dipyridamole, with limited success.

Figure 22-13. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease) with cutaneous lesions of different stages.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), or Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, is a group of autosomal dominant disorders characterized by vascular lesions including telangiectases, arteriovenous malformations, and aneurysms of the skin and internal organs (lung, brain, and GI tract). Epistaxis and GI hemorrhage are the most common complications (see Chapter 36); the incidence of frequent epistaxis ranges from 81% to 96%. The skin lesions are 1- to 3-mm macular telangiectases of the face, lips, tongue, conjunctiva, fingers, chest, and feet (Fig. 22-14). Skin lesions appear later than the epistaxis, usually in the second or third decade of life. In the fifth to sixth decades, recurrent upper and lower GI hemorrhage may occur. Vascular malformations have been reported in the GI tract (46%), liver (26%), lungs (14%), central nervous system (12%), genitourinary tract (1.9%), and almost every other organ system in the body. Management of the GI bleeding may be difficult, but the use of bipolar electrocoagulation or laser techniques has been beneficial (see Chapter 19). Associated von Willebrand factor deficiency may be present, and therapy with desmopressin has been successful in treating massive GI bleeding. There is presently no treatment to prevent the development of telangiectatic lesions in patients with HHT. Chronic therapy with estrogen and progesterone may reduce bleeding from GI telangiectases. Skin and oral lesions similar to those seen in HHT are found in some patients with the CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) variant of scleroderma. The extent of cutaneous sclerosis may be limited in patients with CREST, so differentiation by physical examination may be difficult. Epistaxis is uncommon in patients with CREST and almost universal in patients with HHT. In addition, patients with CREST have anticentromere antibodies in their serum that are not found in patients with HHT.

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome is a rare disorder of the skin and GI tract composed of a constellation of multiple cutaneous and GI venous malformations. Most cases are sporadic. In affected patients, blue, subcutaneous, compressible nodules develop on the skin (Fig. 22-15). GI vascular malformations are common, especially in the small intestine or colon, and bleeding is an almost universal feature. Acute GI hemorrhage, intussusception, volvulus, bowel infarction, and rectal prolapse have been described. Treatment is primarily surgical or with photocoagulation.

Amyloidosis commonly has prominent cutaneous and oral manifestations. Waxy papules around the eyes, nose, and central face—as well as purpura involving the face, neck, and upper eyelids—are frequently noted. If a waxy papule is pinched, hemorrhage will ensue (pinch purpura). Orbital purpura after endoscopy, vomiting, or coughing is almost diagnostic. Macroglossia, increased tongue firmness, enlarged submandibular structures, and lingual indentations from the teeth occur in 20% to 50% of patients. The macroglossia may interfere with eating and closing the mouth and may cause airway obstruction, especially in the reclining position. The tongue may be enlarged and highly vascular, resulting in bleeding. Recurrent hemorrhagic bullae in the mouth are common. Patients may have carpal tunnel syndrome, edema, the shoulder pad sign (amyloid deposits in soft tissues around shoulders), GI bleeding (see Chapter 35), peripheral neuropathies, rheumatoid arthritis–like deposits in small joints, and cardiac involvement. Congestive heart failure or arrhythmias account for death in 40% of patients with systemic amyloidosis. Diagnosis of amyloidosis can be made by subcutaneous fat aspiration or by bone marrow, rectal, skin, or tongue biopsy.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is a rare disorder characterized by aberrant calcification of mature elastic tissue. Skin lesions are usually the initial manifestation, appearing in the second decade as yellow to orange papules (“plucked chicken skin”) on the lateral neck (Fig. 22-16). Skin lesions may progress caudally, involving other flexural areas (e.g., axilla, groin, antecubital and popliteal fossae). Calcification of the elastic tissue of arteries leads to the major complications—retinal bleeding, intermittent claudication, premature coronary artery disease, and GI bleeding. From 8% to 13% of patients experience GI bleeding, which is usually from the stomach, and often no specific bleeding point is found. As opposed to the other complications of pseudoxanthoma elasticum just noted, GI bleeding tends to occur in younger patients (average age, 26 years), often occurs during pregnancy, and may be recurrent. Skin lesions may not be visible at the time of bleeding. Because apparently normal flexural or scar skin may yield diagnostic findings, a blind skin biopsy may be indicated in a young person with GI bleeding with no other explanation. Lesions identical to those seen on the skin may also be present on the lower lip and the rectal mucosa.

Figure 22-16. Characteristic “plucked chicken skin” appearance in a patient with pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

(Courtesy of Dr. Victor Newcomer.)

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1, von Recklinghausen’s disease) is defined by its cutaneous manifestations of six or more café au lait spots (each with a diameter more than 5 mm in prepubertal persons and more than 15 mm in postpubertal persons), multiple soft papules (neurofibromas; Fig. 22-17), or a single plexiform neurofibroma, and freckling of the axillae or inguinal areas. GI involvement occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with NF1. Intestinal neurofibromas may arise at any level of the GI tract, although small intestinal involvement is most common. These tumors are generally submucosal but may extend to the serosa. Dense growths known as plexiform neurofibromatosis of the mesentery or retroperitoneal space may lead to arterial compression or nerve injury. Other tumors may occur in neurofibromatosis. There is an increased incidence of pheochromocytoma, with or without the multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIB syndrome.40 Duodenal and ampullary carcinoid tumors (sometimes producing obstructive jaundice; see Chapter 31), malignant schwannomas, sarcomas, and pancreatic adenocarcinomas are seen with increased frequency. Clinical manifestations include abdominal pain, constipation, anemia, melena, and an abdominal mass. Serious complications that have been reported include intestinal or biliary obstruction, ischemic bowel, perforation, and intussusception. Involvement of the myenteric plexus has resulted in megacolon.

Mastocytosis is characterized by mast cell infiltration of the bone marrow, skin, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and GI tract. It occurs in adult and pediatric patients (see Chapter 35). In children, the most common lesions consist of a large red to brown plaque (solitary mastocytoma), multiple red to brown papules or plaques (urticaria pigmentosa), or diffuse cutaneous involvement, with or without flushing or blistering. In adult patients, most have urticaria pigmentosa–type lesions (Fig. 22-18), sometimes with prominent telangiectasia. Lesions often are on the trunk. The most common GI complaint is dyspepsia and often peptic ulcer disease caused by histamine-induced gastric hypersecretion (see Chapter 49). Diarrhea and abdominal pain are also common problems and can be accompanied by malabsorption.41 In children, the lesions usually involute spontaneously, and systemic disease is uncommon. In adults, cutaneous lesions may resolve as well, but without improvement in systemic symptoms. In the rare pediatric case with a solitary mastocytoma and significant systemic symptoms, excision of the skin lesion may resolve the systemic complications. Extracutaneous involvement should be considered for adult patients with cutaneous mastocytosis because management of symptoms can easily be achieved.

Figure 22-18. An adult with urticaria pigmentosa. Reddish-brown freckle-like lesions are characteristic of the adult form of this disease.

Connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis (DM), and progressive systemic scleroderma (PSS) all have characteristic skin and GI manifestations (see Chapter 35). SLE patients prototypically have malar erythema with photosensitivity and often erythematous raised patches with follicular plugging (discoid lupus). SLE patients can have oral ulcers, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, peritonitis with ascites, autoimmune hepatitis, and pancreatitis. DM is described in greater detail later, but patients with DM can have oropharyngeal dysphagia and large bowel infarction from vasculopathy (especially in juvenile DM). Patients with PSS often demonstrate generalized sclerotic skin or, less commonly, morphea (sclerotic plaques with ivory-colored centers), matted telangiectasia, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Esophageal dysfunction is the most common internal symptom, although the small intestine may also be affected, producing constipation, diarrhea, and bloating.

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS OF GASTROINTESTINAL MALIGNANCIES

POLYPOSIS SYNDROMES

Gardner’s syndrome, or familial adenomatous polyposis, is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (see Chapter 122). The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene on chromosome 5q21 is mutated in the germline of these patients. Cutaneous features of this syndrome occur in more than 50% of affected individuals and often appear before the polyps become symptomatic. Multiple epidermoid cysts (also called inclusion cysts) of the face, scalp, and extremities appear before puberty. This is in contrast with common epidermoid cysts, which usually appear on the back and occur after puberty. True sebaceous cysts (steatocystomas) are not associated with Gardner’s syndrome. The oral manifestations of Gardner’s syndrome include the presence of 1- to 10-mm osteomas and multiple unerupted, supernumerary teeth.

Muir-Torre syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome with cutaneous sebaceous neoplasms and multiple primary cancers, especially of the proximal colon.42,43 It is part of the cancer family syndrome (CFS), or Lynch II syndrome. The most prominent cutaneous manifestation is one or more sebaceous neoplasms of various degrees of differentiation, from benign adenoma to aggressive sebaceous carcinoma. Because cutaneous sebaceous neoplasms are rare, even the presence of one lesion should prompt evaluation for this syndrome. In addition, keratoacanthomas and basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin develop in these patients. Multiple primary (low-grade) malignancies are characteristic; in one series, 40 patients had a total of 106 tumors and 1 patient had nine different primary carcinomas. The most common location for carcinomas is the GI tract (93%), especially the proximal colon. One or more polyp(s) of the intestine have been described in 38% of patients, but multiple adenomatous polyposis is absent in this syndrome.43 Urogenital carcinomas, especially of the endometrium, bladder, and kidney, occur in 50% of patients. The defects leading to this phenotype are found in the DNA repair genes MLH1 and MSH2 on chromosome 3p.43

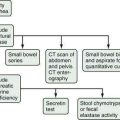

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome of GI hamartomas and mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation (Fig. 22-19). The macules appear during infancy and early childhood. Mucosal lesions persist, whereas the cutaneous lesions fade over time. The hyperpigmented lesions consist of dark brown 1-mm to 1-cm macules on the lips (95%), buccal mucosa (83%), and acral areas (palms, soles, digits), and around the eyes, anus, and mouth. The most common associated malignancy is duodenal carcinoma; granulosa theca cell tumors of the ovary may be present in up to 20% of female patients. The patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome may carry an overall relative risk of cancer of up to 18. The cause is a mutation in the STK11 gene (see Chapters 3 and 122).44 Confusion may occur between Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, which is a benign oral and acral lentiginous pigmentation disorder. In Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, the pigmented macules involve the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa and nails. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome is best differentiated from Peutz-Jeghers syndrome by its lack of personal or family history for GI cancers and lack of physical finding for lentigines that cross the vermillion border.45,46

Cowden’s syndrome, or multiple hamartoma syndrome, is an uncommon autosomal dominant syndrome with multiple mucocutaneous manifestations and an increased risk of malignancy. The diagnostic skin lesions are multiple facial verrucous lesions that histologically are trichilemmomas. Oral papillomatosis is common. Thyroid disease (goiter, adenoma, cancer) are important components of the syndrome, as is fibrocystic disease of the breast (60%) and breast carcinoma (29%) in affected women. GI lesions occur in at least 40% of patients and consist primarily of multiple polyps, which occur anywhere along the GI tract, most commonly the colon. These polyps are usually small and predominantly hamartomatous. The gene mutation responsible is PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), found on chromosome 10q.47

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is a rare sporadic syndrome of generalized GI polyposis, mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation, alopecia, malabsorption with malnutrition, and nail dystrophy.48 The mean age at onset is 59 years. Diarrhea, weight loss (usually more than 10 kg), and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms. Nail changes (90% of patients) affect all 20 nails and consist of thinning and splitting of nails, onycholysis (separation of the nail from the nail bed), or total shedding of the nails. Alopecia (more than 95% of patients) is usually sudden and involves not only the scalp but also the body hair. Hyperpigmentation occurs in about 85% of patients and has been described as lentigines that may coalesce, most commonly on the upper extremities, lower extremities, palms, and soles. The cutaneous changes all resolve with treatment but may resolve spontaneously even with continued GI disease. Death occurs in about half of patients as a result of persistent diarrhea or malnutrition. Aggressive nutritional support in the form of total parenteral nutrition has led to complete resolution of the syndrome, suggesting that at least some of the manifestations are a complication of the metabolic abnormalities caused by the severe diarrhea.

INTERNAL MALIGNANCY AND RELATED DISORDERS

Dermatomyositis is manifested by a violaceous color of the eyelids, often with edema (heliotrope); keratotic papules over the knuckles (Gottron’s papules; Fig. 22-20); a widespread erythema, often with accentuation over the elbows and knees (Gottron’s sign), resembling psoriasis; photosensitivity; and nail cuticle abnormalities, including telangiectases, thickening, roughness, overgrowth, and irregularity. About 25% of patients with dermatomyositis have internal malignancy, particularly in patients older than 50 years.49 Cancers most commonly associated with dermatomyositis are gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, and lung cancer and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is the most commonly associated malignancy in the Chinese population. There does not appear to be a predilection for either gender. To detect an associated cancer, a complete medical history, physical examination, including rectal, pelvic, and breast examinations, CBC, routine serum chemistry analysis, serum protein electrophoresis, multiple fecal occult blood tests, a urinalysis, chest roentgenography, and mammography (in women) are recommended. Any abnormalities should be investigated further. Extensive blind evaluation of patients with dermatomyositis is not warranted.50,51

Figure 22-20. Dermatomyositis with erythematous plaques, especially over the knuckles (Gottron’s papules).

(Courtesy of Dr. Timothy Berger, San Francisco, Calif.)

Keratosis palmaris et plantaris (Howel-Evans syndrome; tylosis and esophageal cancer) is an adult-onset diffuse hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles that has been described in association with a very high incidence of esophageal carcinoma in several kindred in Liverpool, England. It is an autosomal dominant phenotype caused by loss of heterozygosity of the TOC gene on chromosome 17q.52 The skin lesions appear during adolescence or early adulthood, and the carcinomas appear on the average at 45 years. Esophageal carcinoma develops in almost all patients in these kindred with tylosis.52

Tripe palms, also called acanthosis nigricans of the palms, acanthosis palmaris, pachydermatoglyphy, palmar hyperkeratosis, and palmar keratoderma, is a paraneoplastic phenomenon characterized by a moss-like or velvety texture with pronounced dermatoglyphics or by a cobbled or honeycombed surface of the palms and fingers. Of reported cases of tripe palms, 91% have occurred in association with neoplasm. Gastric and lung cancers were the most common neoplasms, each accounting for more than 25% of all the malignancies.53

Acanthosis nigricans is a cutaneous finding that manifests with a velvety hyperplasia and hyperpigmentation of the skin of the neck and axillae (Fig. 22-21), often associated with multiple skin tags. Some patients with acanthosis nigricans have internal malignancy, so-called malignant acanthosis nigricans. In these patients, the extent of involvement may be severe, including the hands, genitalia, and oral mucosa. The associated carcinoma is usually present simultaneously with the acanthosis nigricans but may not yet be clinically evident. Intra-abdominal adenocarcinomas constitute more than 85% of associated malignancies, with gastric carcinomas representing more than 60%. Survival is short, and more than 50% of patients die in less than one year.

Carcinoid tumors produce a number of vasoactive substances that can induce cutaneous flushing (see Chapter 31). The most common carcinoid tumors (appendix and small bowel) do not produce flushing until the vasoactive substances reach the systemic circulation. Flushing, therefore, generally denotes metastasis to the liver or a different primary tumor site (e.g., lung or ovary).

Glucagonoma of the pancreas often precipitates necrolytic migratory erythema of the skin. The rash is common around orifices, flexural regions, and the fingers. Lesions are typically papulovesicular, with secondary erosions, crusting, and fissures appearing in a geographic circinate pattern (Fig. 22-22). Patients can also often have weight loss, diarrhea, anemia, psychiatric disturbances, hypoaminoacidemia, and diabetes. The rash typically clears with successful removal of the tumor (discussed in more detail in Chapter 32).

Subcutaneous fat necrosis and polyarthralgia is associated with pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma, pancreatitis, and pancreatic pseudocysts. Most affected persons are men. Deep, subcutaneous, erythematous nodules ranging from 1 to several centimeters in diameter usually appear on the legs. In uncommon cases, the nodules may break down, exuding a creamy material. Arthritis of one or several joints, especially the ankles and knees, may accompany the nodules or occur without skin lesions. Abdominal pain may be absent when the skin lesions or arthritis occur. In addition to the expected elevations of serum amylase and lipase levels, eosinophilia is common. Histopathologic evaluation of skin lesions usually reveals diagnostic findings—pale staining necrotic fat cells (ghost cells) and deposits of calcium in the necrotic fat. The mortality rate in cases not associated with carcinoma approaches 50%. Subcutaneous swellings, which commonly break down and drain, may also be seen in patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency. These nodules usually occur on the buttocks or proximal extremities and are often precipitated by trauma. In pancreatitis, subcutaneous nodules usually manifest on the anterior shins. A bluish discoloration of the skin (ecchymosis) around the umbilicus, sometimes associated with hemorrhagic pancreatitis, is called Cullen’s sign; when a similar process occurs in the flank, it is called the Grey-Turner sign (see Chapter 58 for example).

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS OF LIVER DISEASE

In addition to jaundice, patients with liver disease may show vascular spider angiomata, corkscrew scleral vessels, palmar erythema, telangiectasia, striae, and caput medusa.54 Patients with hemochromatosis often develop a generalized bronze-brown color with accentuation over sun-exposed sites. Primary biliary cirrhosis may be associated with xanthomas that involve the trunk, face, or extremities. Striking plane xanthomas may develop on the palmar creases (see Chapter 89). Patients with sarcoidosis involving the liver or, less commonly, the GI tract may have sarcoid skin lesions (Fig. 22-23).

Figure 22-23. Patient with sarcoidosis manifesting as an annular plaque on the face.

(Courtesy of Dr. Timothy Berger, San Francisco, Calif.)

The association between polyarteritis nodosa and hepatitis B is well documented. Urticaria and serum sickness occur more commonly in patients with hepatitis B, although both have been reported in association with hepatitis C (see Chapters 78 and 79). Chronic hepatitis C virus is associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis with cryoglobulinemia. Petechiae and palpable purpura are noted on the skin.

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is a metabolic disorder characterized by skin fragility, blisters, hypertrichosis, and hyperpigmentation in sun-exposed skin (Fig. 22-24). PCT is the most common form of porphyria and is characterized by a deficiency of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase. Diagnosis is typically made with a 24-hour urine collection demonstrating elevated porphyrin levels, specifically uroporphyrin. Alcohol consumption, estrogens, iron, and sunlight all are known to exacerbate PCT. There is a clear and substantial link between PCT and hepatitis C.55 The prevalence of hepatitis C in patients with PCT demonstrates regional variation, ranging from 65% in southern Europe and North America to 20% in northern Europe and Australia.54 Treatment involves phlebotomy and antimalarial agents.

Lichen planus is a common, idiopathic, inflammatory disorder that can affect skin, hair, mucous membranes, and nails (see earlier). The prototypical presentation of lichen planus is violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules of flexural areas of the wrists, arms, and legs. The papules often have an overlying reticulated white scale known as Wickham’s striae. An association between lichen planus and hepatitis C exists but is not as prominent as the link between PCT and hepatitis C.56

DRUG-INDUCED LIVER DISEASE IN PATIENTS WITH SKIN DISEASE

Dermatologists frequently consult gastroenterologists for evaluation of patients who are being treated with methotrexate or retinoids, because these medications can cause acute and chronic liver disease (see Chapter 86). Methotrexate is the more commonly used of these medications. It is extremely effective for severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and is also used for cutaneous T cell lymphoma, connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, and other dermatologic and GI disorders. Methotrexate is usually given as a single weekly dose of 10 to 25 mg, but may be used in higher dosages in selected patients. A grading system for liver biopsies has been established and is generally followed by dermatologists (Table 22-2). Current American Academy of Dermatology guidelines recommend pretreatment liver biopsies and repeated biopsies during therapy, depending on the results of regular liver chemistry tests and determination of other risk factors for hepatic disease (obesity with diabetes, results of prior liver biopsies, and alcohol consumption). Decisions on continuation of treatment are frequently based on the results of these biopsies.57 An American College of Gastroenterology committee has made similar recommendations (Table 22-3).

Table 22-2 Grading System for Liver Biopsy Findings in Patients Taking Methotrexate

| GRADE | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| I | Normal; mild fatty infiltration; nuclear variability, portal inflammation |

| II | Moderate to severe fatty infiltration; nuclear variability; portal tract expansion, portal tract inflammation, and necrosis |

| IIIA | Mild fibrosis (fibrosis denotes formation of fibrotic septa extending into the lobules) |

| IIIB | Moderate to severe fibrosis |

| IV | Cirrhosis (regenerating nodules as well as bridging of portal tracts must be demonstrated) |

From Roenigk HH Jr, Auerbach R, Maibach H, et al: Methotrexate in psoriasis: Consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38:478-85.

Table 22-3 Guidelines for Continuation of Methotrexate Therapy*

* Based on the results of liver biopsy (see Table 22-2).

From Roenigk HH Jr, Auerbach R, Maibach H, et al: Methotrexate in psoriasis: Consensus conference. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38:478-85.

PARASITIC DISEASES OF THE INTESTINE AND SKIN

The larval forms of human and animal nematodes may cause migratory erythematous skin lesions, called creeping eruptions (see Chapter 110). The most common pattern is cutaneous larva migrans, caused by dog and cat hookworms (Fig. 22-25). Pruritic linear papules migrate at a rate of 1 to 2 cm daily on skin sites, usually the feet, buttocks, or back, that have come in contact with fecally contaminated soil. Lesions resolve spontaneously over weeks to months. Larva currens is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis larva migrating in the skin. It occurs in two forms, a form localized to the perirectal skin in immunocompetent hosts and a disseminated form occurring in immunosuppressed hosts. S. stercoralis has the unique capacity among nematodes to develop into infective larvae within the intestine. These infective larvae may invade the perirectal skin in infected immunocompetent individuals, causing urticarial, erythematous, linear lesions that migrate up to 10 cm a day, usually within 30 cm of the anus. Skin lesions may occur intermittently, making diagnosis difficult. In immunosuppressed hosts, repeated autoinfection through the intestine leads to a tremendous parasite burden (hyperinfection), manifested most commonly by pulmonary disease. In association, disseminated larva currens–type lesions may appear over the whole body, especially the trunk. Petechial or purpuric serpiginous lesions may also occur periumbilically.

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS AND CELIAC DISEASE

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an extremely pruritic skin disorder most commonly appearing during early adulthood (see Chapter 104). The cutaneous eruption consists of urticarial, vesicular, or bullous lesions characteristically localized to the scalp, shoulders, elbows, knees, and buttocks.58 The disorder is so pruritic that often all the skin lesions have been excoriated, and the diagnosis must be suspected on the basis of this and the distribution (Fig. 22-26). The diagnosis of DH is established by skin biopsy and direct immunofluorescence examination of the skin. Deposits of IgA are found in the dermal papillae at sites of itching and where vesicles are forming. Patients with DH commonly have an enteropathy indistinguishable from celiac disease. Their human leukocyte antigen (HLA) patterns, including haplotypes B8, DR3, and DQw2; abnormalities of intestinal absorption; antiendomysial and antigliadin antibodies; and small bowel biopsy findings are similar to those of patients with celiac disease, and yet fewer than 5% of patients with DH have symptomatic GI disease. Gluten has been shown to be the dietary trigger of DH. Patients, even those with such minimal bowel disease that the bowel biopsy finding is normal, improve on a gluten-free diet. Reintroduction of gluten in a symptom-free patient on a gluten-free diet leads to the reappearance of pruritus and skin lesions. The IgA antibodies deposited in the skin and causing the eruption have not been proved to originate in the gut, and do not seem to be directed against gluten. The pathogenesis remains unknown.

Because it is occasionally difficult to distinguish DH from other blistering skin diseases, a patient with an extremely pruritic eruption may be referred for endoscopy. The finding of an abnormal small intestine consistent with celiac disease in a patient with a pruritic eruption would be highly suggestive of DH (see Chapter 104). The skin lesions of DH respond dramatically to sulfa drugs (dapsone or sulfapyridine), but the gut pathology and skin immunofluorescence are unchanged by sulfa drugs. Treatment with a gluten-free diet leads to gradual clearing of skin lesions, improvement of the intestinal abnormality, disappearance of the IgA from the skin, and decreased dependence on dapsone for control of the cutaneous eruption.59

VITAMIN DEFICIENCIES

See also Chapters 4 and 100.

Pellagra, a deficiency of niacin, may be related to inadequate diet, medication (isoniazid), or the carcinoid syndrome.60 The lesions appear symmetrically in sun-exposed areas as brown-red, blistering, or scaling plaques, which may become indurated. Glossodynia, atrophic glossitis and, sometimes, ulcerative gingivostomatitis may be present. In addition to dermatitis (with or without oral lesions), diarrhea and dementia may occur (the three Ds), as may death if untreated.

Deficiencies of zinc (acrodermatitis enteropathica), essential fatty acids, and biotin all produce a superficial scaling and an occasionally blistering eruption accentuated in the groin and around the mouth (Fig. 22-27). Alopecia is often present. These conditions are most common in children with congenital metabolic abnormalities, in alcoholics with cirrhosis, and in persons on hyperalimentation who have not been adequately supplemented. Replacement of the deficiency leads to rapid resolution of the dermatitis and alopecia. Acrodermatitis enteropathica also occurs in zinc-deficient patients with Crohn’s disease.61

Scurvy, or vitamin C deficiency, manifests as follicular hyperkeratosis and perifollicular hemorrhage, ecchymoses, xerosis, leg edema, poor wound healing, and/or bent or coiled body hairs.62 Large purpuric plaques, especially on the extremities, may occur (Fig. 22-28). Gingivitis with gum hemorrhage occurs only in dentulous patients and commonly occurs in the presence of poor oral hygiene and periodontal disease.63 Scurvy is most common in alcoholics, but may occur with Crohn’s or Whipple’s disease. The focus of treatment is to correct the vitamin C deficit and to replete body stores. Symptoms recede promptly and disappear within a few weeks.64

As discussed earlier, a characteristic dermatosis called necrolytic migratory erythema63,64 frequently develops in patients with glucagon-secreting tumors of the pancreas (see Fig. 22-22). A skin biopsy specimen may be highly suggestive, showing psoriasiform hyperplasia, a subcorneal blister containing neutrophils, and hydropic degeneration and necrosis of the subcorneal keratinocytes. Manifestations of this syndrome are discussed in Chapter 32. There are also reports of this syndrome occurring without glucagonomas, especially in the setting of cirrhosis and subtotal villous atrophy of the jejunal mucosa.65 Glucagon is therefore probably not the cause of the eruption. Infusion of amino acids has been reported to clear the eruption, despite persistently elevated glucagon levels. Zinc deficiency can cause a similar eruption (acrodermatitis enteropathica), as can biotin-responsive multiple carboxylase deficiency and essential fatty acid deficiency. The eruption seems to be a cutaneous manifestation of several metabolic disorders, but the crucial pathogenic defect has not been determined.66

Airio A, Pukkala E, Isomaki H. Elevated cancer incidence in patients with dermatomyositis: A population-based study. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1300-3. (Ref 49.)

Delahoussaye AR, Jorizzo JL. Cutaneous manifestations of nutritional disorders. Dermatol Clin North Am. 1989;7:559-70. (Ref 60.)

Faure M. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Semin Dermatol. 1988;7:123-9. (Ref 58.)

Karaca S, Seyhan M, Senol M, et al. The effect of gastric Helicobacter pylori eradication on recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:615-7. (Ref 26.)

National Center for Biotechnology Information. Muir-Torre syndrome. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=158320, 2008. (Ref 43.)

Reunala TL. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:728-36. (Ref 59.)

Sardana K, Mishra D, Garg V. Laugier Hunziker syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:998-1000. (Ref 45.)

Tierney EP, Badger J. Etiology and pathogenesis of necrolytic migratory erythema: Review of the literature. MedGenMed. 2004;6:4. (Ref 64.)

1. Zunt S. Evaluation of the dry mouth patient. Alpha Omegan. 2007;100:203-9.

2. Sheikh SH, Shaw-Stiffel TA. The gastrointestinal manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:9-14.

3. Mathews SA, Kurien BT, Scofield RH. Oral manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dent Res. 2008;87:308-18.

4. Bohmer T, Mowe M. The association between atrophic glossitis and protein-calorie malnutrition in old age. Age Ageing. 2000;29:47-50.

5. Gorsky M, Silverman SJr, Chinn H. Burning mouth syndrome: A review of 98 cases. J Oral Med. 1987;42:7-9.

6. Shenefelt PD. Hypnosis in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:393-9.

7. Drage LA, Rogers RSIII. Clinical assessment and outcome in 70 patients with complaints of burning or sore mouth symptoms. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:223-8.

8. Schiffman SS. Taste and smell in disease: I. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1275-9.

9. Schiffman SS. Taste and smell in disease: II. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1337-43.

10. Silverman SJr, Thompson JS. Serum zinc and copper in oral/oropharyngeal carcinoma: A study of seventy-five patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:34-6.

11. Schiffman SS, Zervakis J, Suggs MS, et al. Effect of tricyclic antidepressants on taste responses in humans and gerbils. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:599-609.

12. Gick CL, Mirowski GW, Kennedy JS, et al. Treatment of glossodynia with olanzapine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:463-5.

13. Bruce AJ, Rogers RSIII. Oral psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:99-104.

14. Assimakopoulos D, Patrikakos G, Fotika C, Elisaf M. Benign migratory glossitis or geographic tongue: An enigmatic oral lesion. Am J Med. 2002;113:751-5.

15. Langtry JA, Carr MM, Steele MC, Ive FA. Topical tretinoin: A new treatment for black hairy tongue (lingua villosa nigra). Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:163-4.

16. Mirowski GW, Hilton JF, Greenspan D, et al. Association of cutaneous and oral diseases in HIV-infected men. Oral Dis. 1998;4:16-21.

17. Epstein JB. Antifungal therapy in oropharyngeal mycotic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:32-41.

18. Silverman SJr, McKnight ML, Migliorati C, et al. Chemotherapeutic mouth rinses in immunocompromised patients. Am J Dent. 1989;2:303-7.

19. Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. Significance of oral hairy leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:151-4.

20. Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Overby G, et al. Risk factors for rapid progression from hairy leukoplakia to AIDS: A nested case-control study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:652-8.

21. Ficarra G, Berson AM, Silverman SJr, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the oral cavity: A study of 134 patients with a review of the pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical aspects, and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:543-50.

22. Lumerman H, Freedman PD, Kerpel SM, Phelan JA. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 23 homosexual and bisexual men from the New York metropolitan area. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:711-16.

23. Cattelan AM, Trevenzoli M, Aversa SM. Recent advances in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:451-62.

24. Perkocha LA, Geaghan SM, Yen TS, et al. Clinical and pathological features of bacillary peliosis hepatis in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1581-6.

25. Zunt SL. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:33-9.

26. Karaca S, Seyhan M, Senol M, et al. The effect of gastric Helicobacter pylori eradication on recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:615-17.

27. Casiglia JM, Mirowski GW, Nebesio CL. Aphthous stomatitis. In: Elston DM, editor. Dermatology. St. Petersburg, Fla: EMedicine, 2009. Updated Feb 6

28. Chong VH, Lim CC, Vu C. A rare cause of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:91-3.

29. Korman NJ. New and emerging therapies in the treatment of blistering diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:127-37.

30. Anhalt GJ, Kim SC, Stanley JR, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: An autoimmune mucocutaneous disease associated with neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1729-35.

31. Castillo RO, Davies YK, Lin YC, et al. Management of esophogeal strictures in children with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Pediatr Gastrenterol Nutr. 2002;34:535-41.

32. Fine-Jo D, Bauer EA, Briggaman RD. Revised clinical and laboratory criteria for subtypes of inherited epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:119-35.

33. Lozada-Nur F, Gorsky M, Silverman SJr. Oral erythema multiforme: Clinical observations and treatment of 95 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:36-40.

34. Prendiville J. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Adv Dermatol. 2002;18:151-73.

35. Eisen D. The clinical manifestations and treatment of oral lichen planus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:79-89.

36. Chryssostalis A, Gaudric M, Terris B, et al. Esophageal lichen planus: A series of eight cases including a patient with esophageal verrucous carcinoma. A case series. Endoscopy. 2008;40:764-8.

37. Boh EE, Faleh al-Smadei RM. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:533-46.

38. Scheper HJ, Brand HS. Oral aspects of Crohn’s disease. Int Dent J. 2002;52:163-72.

39. Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children: Report of 100 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1999;78:395-409.

40. Stamm B, Hedinger CE, Saremaslani P. Duodenal and ampullary carcinoid tumors: A report of 12 cases with pathological characteristics, polypeptide content, and relation to the MEN I syndrome and von Recklinghausen’s disease (neurofibromatosis). Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;408:475-89.

41. Horan RF, Austen KF. Systemic mastocytosis: Retrospective review of a decade’s clinical experience at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;Suppl(96):5S-13S.

42. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Adenomatous polyposis of the colon. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=175100, 2008.

43. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Muir-Torre syndrome. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=158320, 2008.

44. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=175200, 2008.

45. Sardana K, Mishra D, Garg V. Laugier Hunziker syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:998-1000.

46. Giardiello FM, Welsh SB, Hamilton SR, et al. Increased risk of cancer in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1511-14.

47. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Cowden disease. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=158350, 2008.

48. Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, et al. The Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982;61:293-309.

49. Airio A, Pukkala E, Isomaki H. Elevated cancer incidence in patients with dermatomyositis: A population-based study. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1300-3.

50. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: A population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100.

51. Callen JP, Wortmann RL. Dermatomyositis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:363-73.

52. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Tylosis with esophageal cancer. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=148500, 2008.

53. Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Almeida L, Kurzrock R. Tripe palms and malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:669-78.

54. Mayo MJ. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C infection. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:135-48.

55. Chuang TY, Brashear R, Lewis C. Porphyria cutanea tarda and hepatitis C virus: A case-control study and meta-analysis of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:31-6.

56. Chuang TY, Stitle L, Brashear R, Lewis C. Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: A case-control study of 340 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:787-9.

57. Roenigk HHJr, Auerbach R, Maibach H, Weinstein GD. Methotrexate in psoriasis: Revised guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:145-56.

58. Faure M. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Semin Dermatol. 1988;7:123-9.

59. Reunala TL. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:728-36.

60. Delahoussaye AR, Jorizzo JL. Cutaneous manifestations of nutritional disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1989;7:559-70.

61. Myung SJ, Yang SK, Jung HY, et al. Zinc deficiency manifested by dermatitis and visual dysfunction in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:876-9.

62. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906.

63. Norton JA, Kahn CJ, Schiebinger R, et al. Amino acid deficiency and the skin rash associated with glucagonoma. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:213-15.

64. Tierney EP, Badger J. Etiology and pathogenesis of necrolytic migratory erythema: Review of the literature. MedGenMed. 2004;6:4.

65. Doyle JA, Schroeter AL, Rogers RS. Hyperglucagonaemia and necrolytic migratory erythema in cirrhosis-possible pseudoglucagonoma syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:581-7.

66. Shepherd ME, Raimer SS, Tyring SK, Smith EB. Treatment of necrolytic migratory erythema in glucagonoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:925-8.