22 Oral Analgesics for Chronic Low Back Pain in Adults

KEY POINTS

Introduction

The most common type of pain for which patients seek medical attention is back pain. Chronic back pain is associated with a reduced quality of life, depression, loss of sleep, and reduced psychosocial and physical function. Analgesic medications are used to treat chronic pain, in conjunction with traditional physical modalities and therapy. Treatment with analgesic medications can help to restore physical and social function, while improving sleep,mood and concentration. Side effects should be minimized as best as possible.1 Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), along with pain modulators, are on the first step of the analgesic ladder to treat mild to moderate pain, as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Opioid analgesics are added as a second-line treatment for moderate to severe pain. 2 Adjuvant medications are used to treat conditions contributing to pain such as altered neuronal function or muscle spasm. An example would be an antidepressant or anticonvulsant medication to treat neuropathic pain from a lumbar radiculopathy. Muscle relaxants can be used to treat muscle spasm.2,3

When treating the elderly, it is important to use a medication with the shortest possible half-life as well as the lowest effective dose, as the elderly population is more prone to side effects. Sedative effects of medications can cause significant confusion and thereby impair function and increase the risk of falling. In the elderly, metabolism of medications is reduced with reduced renal clearance. Therefore, buildup of medication is more likely, placing patients at a higher risk of side effects, especially when combined with other drugs. However, when pain is continuous, a long-acting analgesic medication should be considered5. Elderly and medically ill patients are more prone to toxic renal and hepatic side effects. Also, drugs have variable effects on the liver’s cytochrome P450 system, which vary between individuals; therefore it is important for medications to be obtained from one pharmacy, which can then monitor for medication interactions.

Nonopioid Analgesic Agents: Acetaminophen, Nsaids, Aspirin

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is one of the most commonly used medications both by prescription and over the counter, either by itself or in combination with other products. Acetaminophen is used for the treatment of mild to moderate pain. It is also an antipyretic, but does not have significant antiinflammatory properties. Although considered a safe drug, acetaminophen has a very narrow therapeutic index, thus making a safe dose and a dose able to contribute to liver toxicity very close to each other. The once recommended 1000 mg per dose or 4000 mg a day are being reconsidered. The FDA now recommends a lower dose of a max of 3250 mg per day, which can be divided into 5 doses of 650 mg a day. Studies have shown that a 650 mg dose is almost as effective as the 1000 mg for pain and may be a lot safer for patients.17 Due to acetaminophens effects on the liver, chronic use of acetaminophen should be avoided in patients with hepatic impairment, and patients should limit usage of alcohol products (1-2 drinks per day). Long-term overdosing of acetaminophen may result in hepatic necrosis and can be fatal. Patients should be made aware of the possible ease of overdose if they are on many pain medications, such as Percocet®, Vicodin®, and Darvocet®, all of which contain varying doses of acetaminophen.3,5,6

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

All NSAIDs have antiinflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic properties.3,4,6,7 They are commonly used to treat inflammatory conditions, and are used for analgesia in low back pain as well as for the pain and inflammation of many types of arthritis. NSAIDs are characterized as either selective or nonselective COX-2 inhibitors.

The inflammatory cascade can be triggered by a number of causes such as a physical injury or response to infection. In response, at the cellular level, prostaglandins are synthesized by cyclooxygenase. NSAIDs inhibit the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme and therefore reduce production of prostaglandin, usually nonselectively via COX-1 and COX-2 pathways.12 Prostaglandins are thought to sensitize the pain receptors and are involved in peripheral and central pain transmission. The enzyme COX-1 (cyclooxygenase-1) is prevalent, located in most normal cells, and involved in many aspects of physiologic function. COX-2 is more involved in the inflammatory process. COX-2 is expressed in parts of the kidney, brain, and endothelial cells. COX-1 is found in the gastric epithelium and is involved in the formation of cytoprotective prostaglandin. The COX-2–specific inhibitory NSAIDs were formulated to be gastric-protective; however, they do not reduce the risk of other effects of traditional NSAIDs.3, 4, 6, 7, 12 The NSAIDS and aspirin do not affect the lipoxygenase pathway, therefore they do not reduce the formation of an important inflammatory mediator, the leukotrienes.3,4,6,7,12,18

The NSAIDs have a black box warning that includes cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hypertension. The nonselective NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen at low doses, also can interfere with the cardioprotective effect of aspirin. NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen at doses as low as 400 mg, should be taken either 8 hours before or 30 minutes after aspirin, if the aspirin is taken on a daily basis for its cardioprotective effect. If they are taken together then the cardioprotective effect of aspirin may be negated.12 Also, NSAIDs are contraindicated for the perioperative pain of coronary artery bypass grafts, because platelet adhesion and aggregation can be disrupted.4, 5, 6

NSAIDs may increase the risk of renal and hepatic impairment, as well as of gastrointestinal irritation including bleeding and ulceration. GI bleeding risk is increased in the elderly; in smokers; when NSAIDs are used with aspirin; with corticosteroid use, ethanol use, anticoagulation, debilitation, and history of peptic ulcer. The risk of gastric ulceration can be reduced with the use of a proton pump inhibitor, or a prostaglandin analog such as misoprostol. However, despite that there is still an important risk of developing a severe life threatening gastrointestinal bleed.NSAIDs should be taken with food or a large volume of milk or water to reduce GI side effects. 4–6

Congestive heart failure can be aggravated by the increased action of antidiuretic hormone due to NSAID use. Renal circulation is reduced due to reduced prostaglandin synthesis. This can affect the electrolytes at the renal level and lead to fluid retention and edema, a common side effect. Central nervous system side effects include headache and dizziness. NSAIDs should be discontinued if a rash develops from their use, due to the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.4,6

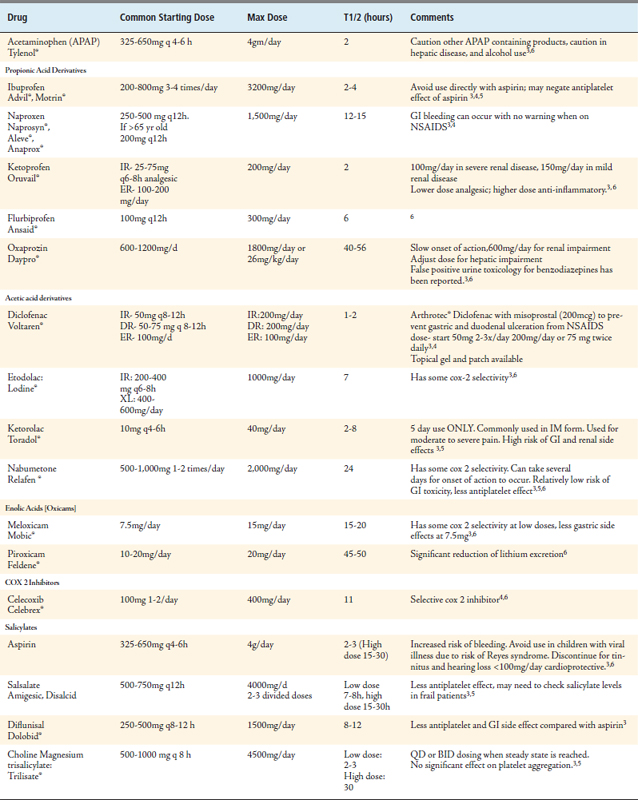

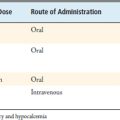

Contraindications to NSAID use include hypersensitivity or allergic reaction to the drug used or any component of its formulation, aspirin, NSAIDs, as well as perioperative use for coronary artery bypass grafting. There is a cross-sensitivity to NSAIDs in those patients who have bronchial asthma, aspirin intolerance, and rhinitis. Avoid NSAIDs in severe hepatic and renal failure. Use caution for uncontrolled hypertension. See Table 22-1 for individual drug descriptions.4,6

Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors (COX-2)

Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors are NSAIDs that specifically inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 and not the cyclooxygenase-1 enzyme at therapeutic concentrations. This effect does give some gastric protection. There still needs to be caution when used in the presence of renal and hepatic disease. The liver enzyme cytochrome P2D6 is inhibited, causing a significant interaction with fluconazole and lithium. COX-2 inhibitors share the same black box warning that the other traditional NSAIDs have.4,6 (See Table 22-1.)

Aspirin

Aspirin prevents the formation of thromboxane A2, which then prevents platelet aggregation by irreversible COX-1 inhibition. Prostaglandin formation is inhibited, as with other NSAIDs.6 (See Table 22-1.)

Flavocoxid (Limbrel®)

Limbrel® also has antioxidant properties. Its efficacy has been similar to that of naproxen in a comparison study for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Limbrel® has been used with patients who are anticoagulated with warfarin. It is recommended to check the prothrombin time 1 to 2 weeks after its initiation. Limbrel® is contraindicated if there is hypersensitivity to it or to flavonoids.8

Opioid Analgesics

Sometimes the use of nonopioids may not be enough to control moderate to severe pain. At this point, according to the WHO, an opioid analgesic may be a good choice for the patient. These medications have a higher potential for abuse and addiction; therefore they are controlled substances in the United States, and require a prescription. The goals of treatment with an opioid include reduction of pain and improved functional status, with no alteration of cognition and compliance with its use.2,9 The three primary opioid receptors are mu, kappa, and delta receptors. Most analgesic medications are selective for the mu receptor, consistent with their similarity to morphine. The mu receptors are located in the central nervous system and in peripheral tissues.9

These receptors have analgesic properties and can also cause drowsiness, clouded cognition, and altered mood. Opioids have rewarding properties associated with their addiction potential as well.6 It is important to be familiar with signs of addiction, physical dependence, and tolerance when prescribing opioid medications.9 Patients also need to be monitored for opioid-induced hyperalgesia, in which opioids can potentially contribute to abnormal pain sensitization.9 The elderly with no history of or current substance abuse are at low risk of addiction. 5 The opioids may cause fewer life-threatening events than chronic NSAID use in the elderly.2

When prescribing opioid medications it is important to be aware of the following commonly used terms. Tolerance is physiologic responce when there is a reduction in effectiveness of a drug with repeated administration.9,18 A patient with tolerance would need a higher dose of medication to get the same effect. Physical dependence is present when there is physical withdrawal from a medication, such as when discontinuing the medication or from rapid dose reduction or when given an antagonist to that medication.9 Addiction has been defined as the compulsive use of a drug despite physical harm.9 Other findings with addiction may also include poor control of drug usage, and cravings.9 Compliance with the use of these medications is done to monitor for abuse, misuse, and drug diversion. A controlled substance agreement is suggested for use. The agreement should state that opioid medication be obtained from one physician, only one pharmacy used, and urine or serum toxicology be done when asked. The agreement should include patient responsibilities and list the risks of treatment. No early refills are recommended, and a police report should be required for lost or stolen prescriptions.9

There are opioid-antagonistic, partial agonist/antagonist medications that have variable binding to the opioid receptors. These medications are reserved for use by the clinician experienced in their use in the patient with opioid addiction.10

Opioid prescriptions are titrated to try to maximize analgesia while minimizing side effects.4 Common side effects to opioid prescriptions (to which a tolerance usually develops) include nausea, mental clouding, and sedation. An antiemetic is commonly needed transiently. Pruritus (itching) and sweating are also common. Caution should be used for the potential risk of respiratory depression, especially when used in patients with respiratory compromise and when added to other CNS (central nervous system) depressants. Elderly patients require careful monitoring and should be on the lowest possible dose. Constipation is a common side effect that generally requires long-term treatment. Alcohol use should be avoided when taking this class of medications. It is essential that alcohol be avoided when on some long-acting formulations, as the time release component can be disrupted and lead to fatality. For chronic pain, long acting opioids should be used as maintenance therapy with limited use of short acting opioids to control breakthrough pain. When discontinuing opioids, they should be tapered to avoid withdrawal symptoms from physical dependence. Pain, blood pressure, mental status, and respiratory status should be monitored while on these medications.4,6

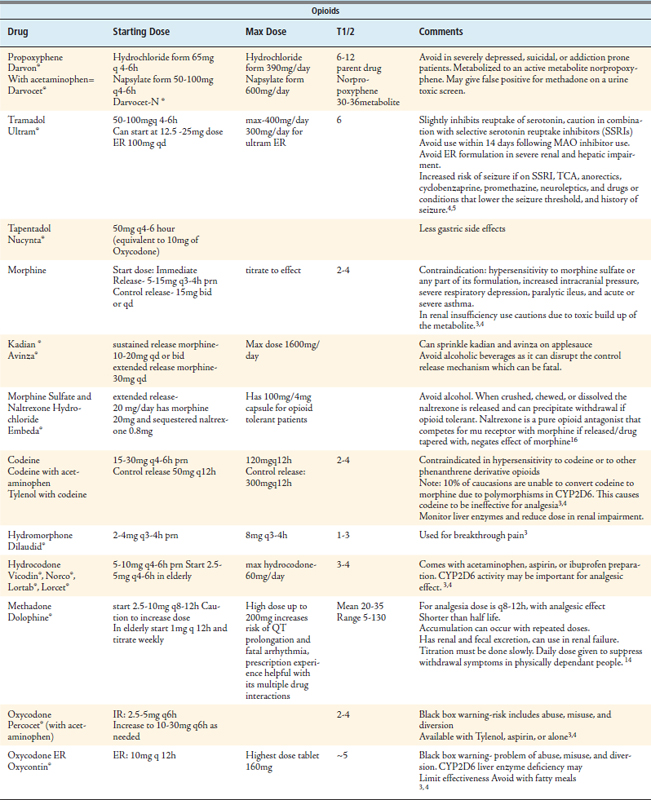

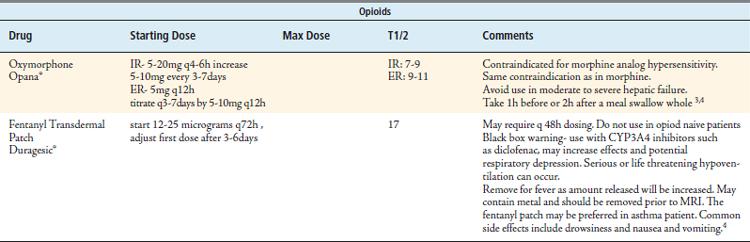

Opioids carry a black box warning to be alert for problems of abuse, misuse, and diversion.3 See Table 22-2 for descriptions of individual drugs.

Muscle Relaxants and Antispasticity Medications

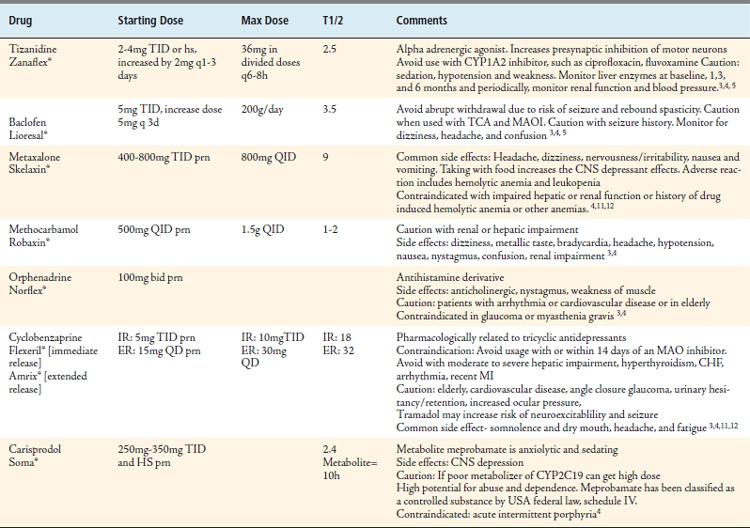

Medications used to treat muscle pain include muscle relaxants and antispasticity medications. The exact mechanism of action of skeletal muscle relaxants is not fully understood. They are thought to disrupt the spasm-pain-spasm cycle, and are recommended to be used for up to 2 weeks at a time. The antispasticity medications tizanidine and baclofen can be used for longer periods of time, and act centrally to reduce hypertonicity in upper motor neuron syndromes. These medications can cause sedation with CNS depression, which may disrupt physical and mental function. Caution must be taken when a patient is also on other medications that can suppress the CNS, and with the use of alcohol.11,12 See Table 22-3 for individual drugs.

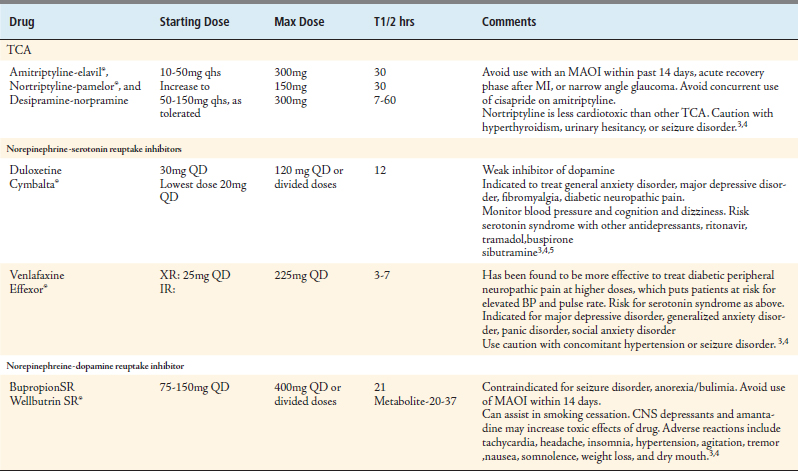

Antidepressants

Antidepressants have been found to have analgesic properties in the treatment of fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have also been found to be effective for headaches. The TCAs act by inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin at the presynaptic neuronal membrane in the CNS. TCAs have anticholinergic side effects that can cause dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, tachycardia, blurred vision, and urinary retention. The risk of cerebral and cardiac intoxication increases with high doses and when combined with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). There is a risk of death from overdosage as well. Avoid use of TCAs after myocardial infarction, in the presence of bundle branch block, with cardiac depressant medications, or in narrow-angle glaucoma. The use of a secondary amine such as nortriptyline is preferred to the use of a tertiary amine such as amitriptyline, due to weaker anticholinergic effects.2,3,12 See Table 22-4.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have fewer side effects and are a better choice for patients with cardiovascular disease. Side effects include nausea, headache, nervousness, and sexual dysfunction. The SSRIs also can cause SIADH with hyponatremia. Alcohol should be avoided with their use. Their use should be avoided in the treatment of bipolar disorder or with an MAO inhibitor. Caution should be used if there is a potential of seizure disorder. The risk of serotonin syndrome is increased when combined with tramadol, MAOIs, TCAs, other SSRIs, bupropion, buspirone, venlafaxine, ritonivir, and sibutramine.3 (See Table 22-4.)

The norepinephrine-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) have side effects including sedation, confusion, hypertension, nausea, sexual dysfunction, constipation, tremor, dry mouth, nervousness, and diaphoresis. Caution must be used due to the risk of serotonijn syndrome when taken with MAOIs, SSRIs, buproprion, buspirone, tramadol, sibutramine, and ritonivir. Their use should be avoided within 14 days of use of an MAOI.3 (See Table 22-4.)

All antidepressants have a black box warning for increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults with major depressive disorder and other psychiatric disorders. The response to treatment should be monitored. Antidepressants should be tapered when discontinued.2–4

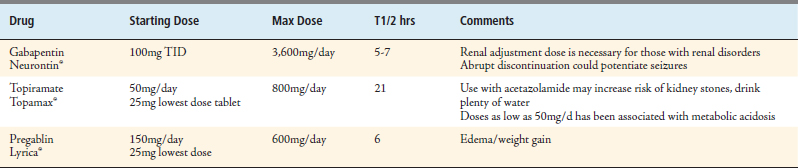

Anticonvulsants

Adjuvant therapy for pain with anticonvulsants is often seen. Drugs in this class most commonly used for the treatment of pain include gabapentin, topiramate and pregabalin (Table 22-5). Gabapentin (neurontin®) is indicated for the treatment of partial seizures, epilepsy, and postherpetic neuralgia, and has off-label uses for chronic pain and and social phobias. Gabapentin’s mechanism of action is not fully understood, but its effects are thought to be due to its ability to increase the inhibitory neurotransmitter effect associated with an increase in GABA. When used for pain, the dose of gabapentin is often higher than its FDA-indicated doses. A normal starting dose is 100 to 300 mg three times a day, increased by 100 mg three times a day every 3 days, to achieve a maintenance dose of 300 to 600 mg/day in divided doses. However, doses of 1200 mg/day up to 3600 mg/day in divided doses have been shown to be the most effective in the treatment of pain.13

Topiramate (Topamax®), another anticonvulsant, also increases the inhibitory effect of GABA. Topiramate is most often used to treat several seizure disorders, but is also commonly prescribed for prophylactic treatment for migraine headaches as well as for neuropathic pain. The initial dose is 50 mg/day, titrating over 8 weeks to reach a peak of 400 mg in divided doses. Doses of 300 mg/day have been shown to be effective in treating back pain.14 Like gabapentin, topiramate is eliminated renally; therefore, dose adjustment is needed for those who are renally impaired. Common side effects include dizziness, somnolence, ataxia, impaired concentration, confusion, fatigue, weight loss, memory difficulties, and speech difficulties. First doses of topiramate can be taken at bedtime to help with the dizziness and somnolence. Topiramate inhibits carbonic anhydrase; therefore there is a higher risk of nephrolithiasis. Patients on this medication should drink plenty of water.18 Topiramate may increase concentrations of phenytoin and decrease levels of valproic acid.

1. Miaskowski C.A., Payne R., Jones W.K. Breakthroughs and challenges in the pharmacologic management of common chronic pain conditions, Clinician. 2005;23(3):1-17.

2. Management of chronic pain in older persons: focus on safety, efficacy, and tolerability of pharmacologic therapy. Clinical Courier. 2005;23(27):1-8.

3. Lussier D., Beaulier P., Huskey A., Portenoy R.K., Fishbain D. 2009 Overview of analgesic agents. Pain Medicine News Special Edition. 2008:27-50.

4. Lacy C.F., Armstrong L.L., Goldman M.P., Lance L.L. Drug information handbook: a comprehensive resource for all clinicians and healthcare professionals, seventeenth ed. Lexi-Comp, Hudson, OH; 2008.

5. Pharmacologic, management of persistent pain in older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009;57:1331-1346.

6. Brunton L., Parker K., et al. Goodman & Gilman’s manual of pharmacology and therapeutics. NY: McGraw Hill NY, 2008.

7. Abramowicz M., Zuccotti G. Drugs for Pain, Treatment guidelines from the medical letter. Med. Lett. Drug. Ther. 2007;5(56):23-32.

8. Physicians’ desk reference, sixthy third edition, Montvale, NJ, 2009.

9. Trescot A.M., Boswell M.V., et al. Opioid guidelines in the management of chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician. 2006;9(1):1-40.

10. Helm S.II, Trescot A.M., Colson J., Sehgal N., Silverman S. Opioid antagonists, partial agonists, and agonists/antagonists: the role of office-based detoxification. Pain Physician. 2008;11:225-235.

11. Toth P.P., Urtis J. Commonly used muscle relaxant therapies for acute low back pain: a review of carisprodol, cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride, and metaxalone. Clin. Ther.. 2004;26(9):1355-1367.

12. Freedman M.K., Saulino M.F., Overton E.A., Holding M.Y., Kornbluth I.D. Interventions in chronic pain management. 5. Approaches to medication and lifestyle in chronic pain syndromes. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008;89(Suppl. 1):S56-S60.

13. Yildirim K., Sisecioglu M., Karatay S., et al. The effectiveness of gabapentin in patients with chronic radiculopathy. Pain Clin.. 2003;15:213-218.

14. Muehlbacher M., Nickel M.K., Kettler C., Tritt K., Lahmann C., Leiberich P.K., et al. Topiramate in treatment of patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin. J. Pain. 2006;22:526.

15. Gallagher R. Methadone: an effective, safe drug of first choice for pain management in frail older adults. Pain Med. 2009;10(2):319-326.

16. Embeda CII (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) extended release capsules prescribing information. Bristol, Tenn: King Pharmaceuticals, Inc, 2009.

17. Anon. Acetaminophen overdose and liver injury-background and options for reducing injury. Food and Drug Administration: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/09/briefing/2009-4429b1-01-FDA.pdf

18. Laurence L. Brunton, Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics, eleventh ed. (2006) New York.