Chapter 32 Opioid Agents in the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome

Opioid medications prove particularly beneficial in patients with severe restless legs syndrome (RLS) or who have developed complications, such as augmentation, on other therapy. Although addiction and side effects require close monitoring, it is of interest that neither frequent addiction nor major complications have yet been reported in RLS patients who are treated with opioids.

Reports of the benefit of opioids for the symptoms of RLS and periodic limb movements of sleep go back at least 300 years. Sir Thomas Willis1 recommended laudanum for a condition that would likely meet current diagnostic criteria for restless legs syndrome. In 1945, Ekbom2 reported on the benefits of codeine and morphine in his seminal paper about RLS. He offered further support for the use of opioids in his paper of 1960.3 Research studies that have often involved only a small number of RLS patients support the use of various opioids, including propoxyphene,4 tramadol,5 oxycodone,6–8 hydrocodone,6 and methadone.8,9 This chapter reviews the properties of opioid agents and the limited literature on their use in RLS, highlighting the benefits and risks of this pharmacological class in the management of RLS.

Brief History and Properties of Opioid Agents

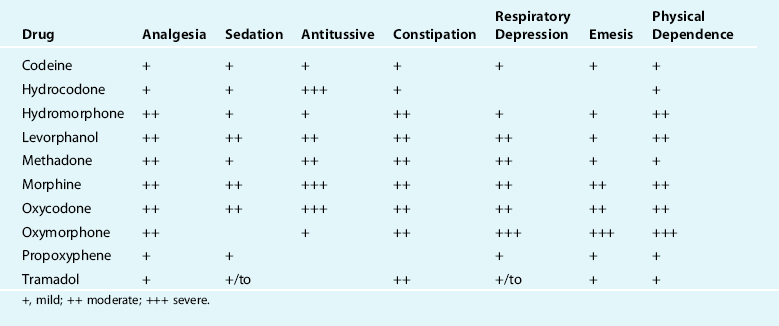

Table 32-1 rates the physiological effects of the most common therapeutic opioids.

Opioid Agents as Analgesics

Relief of acute and chronic pain remains the primary therapeutic role of opioid agents. The human body naturally produces its own opioid-like substances that function as neurotransmitters. The endogenous opioids include endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphin. Endogenous opioids modulate reactions to pain, hunger, and thirst and are also involved in mood control, immune response, and other processes. Exogenous opioids such as morphine bind to the same receptors as endogenous opioids. There are three types of receptors that are widely distributed throughout the brain: mu, delta, and kappa receptors. These G protein–coupled receptors influence the opening of Na+ channels through second messengers, reducing the excitability of neurons that signal pain and inducing euphoria.

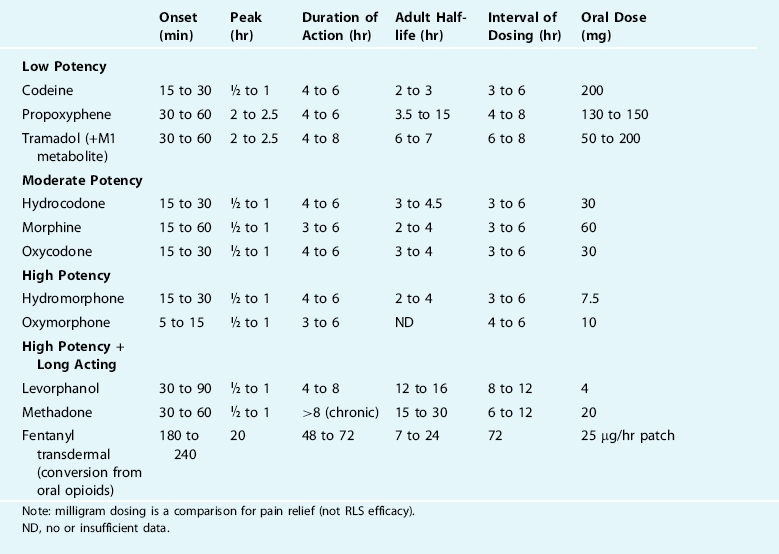

Table 32-2 describes the pharmacokinetics and compares the relative potencies of the common opioid analgesics.

Experimental Manipulation of Opioid Activity in Restless Legs Syndrome

Walters10 has reviewed the literature on opioid receptors, agonists, and antagonists in RLS. Studies have shown differing influences of the antagonist naloxone on the symptom presentation in RLS. Hening and colleagues11 reported on the benefit to five RLS patients when they were successfully treated with various opioid agents. Naloxone, a mu receptor antagonist, was given parenterally to two patients on opioid therapy and resulted in reappearance of RLS symptoms. A more recent study by Winkelmann and associates12 did not demonstrate an influence of opiate receptor blockade on RLS symptoms in untreated patients. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design, eight drug-naïve RLS subjects received naloxone and metoclopramide, a dopamine antagonist. Neither agent provoked the presentation of RLS symptoms. Winkelmann and colleagues concluded that any mechanism for RLS must be in specific dopaminergic or opioidergic pathways rather than a generalized change in neurotransmitter function.12

In 1991, Montplaisir and colleagues13 reported on a single severe RLS patient who was studied in the sleep laboratory while medication-free, while taking codeine sulfate, and while taking codeine sulfate and pimozide. When the patient was treated with codeine sulfate, RLS complaints and periodic leg movements of sleep showed a statistically significant reduction. When the codeine-treated patient received pimozide, a dopamine antagonist, the RLS symptoms that were measured by the forced immobilization test worsened even though the sleep parameters and PLMS remained unchanged. Montplaisir and colleagues opined that the primary neurotransmitter system in the etiology of RLS was dopaminergic in origin with the opiate pathway modulating the dopamine effect.13

There have been two case reports of the development of RLS during opioid withdrawal. Scherbaum and associates14 identified two opioid addicts who developed transient RLS during withdrawal of opioids. Both were successfully treated with levodopa/benserazid. The authors then completed a chart review of 120 opioid-dependent patients who had undergone opioid detoxification. Fifteen of the 120 patients identified symptoms that suggested transient RLS during detoxification.14 In another study involving abrupt discontinuation of tramadol that had taken for 1 year, a single subject developed a variety of withdrawal symptoms that included symptoms of RLS.15 Tramadol and its M1 metabolite are weak mu receptor agonists with serotoninergic and norepinephric activity. In an open-label trial, tramadol demonstrated significant benefit in 10 of 12 RLS patients.5 In the single case report by Freye and Levy,15 it is uncertain whether the symptoms of RLS were present before initiation of tramadol.

Opioid Agents in the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome

The practice guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine identify the benefit of opioids in the treatment of RLS.16 A more recent treatment algorithm that has been proposed by the Medical Advisory Board of the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation includes opioid therapy for any severity level of RLS. This 2004 algorithm considers opioid agents to have a particular role in patients who have failed first-line therapy with dopamine agonists or as initial therapy in patients who have severe to very severe RLS.17 The algorithm recommends close monitoring of patients who are treated with opioid agents to avoid complications or addiction.

Most published reports of opioids in the treatment of RLS have used open-label trials. Reports of small sample size of codeine,2,3 oxycodone,6–8 hydrocodone,6,8 propoxyphene,4 tramadol,5 and methadone8,9 demonstrate efficacy in managing RLS symptoms. The limitations of these reports of efficacy include small sample size and the lack of placebo control. The response to placebo is fairly high in large-scale studies that have been done with carbamazepine,18 ropinirole,19,20 and pramipexole.21

There are only two placebo-controlled trials in a small number of patients that demonstrate the efficacy of oxycodone and propoxyphene. Walters and associates22 reported in 1993 on the benefits of oxycodone in RLS. In a double-blind, randomized, crossover trial that compared oxycodone and placebo; 10 of 11 moderate-severe RLS patients chose oxycodone as their preferred agent for therapy. Using 2 weeks of treatment with a 3-day withdrawal but no washout period, this crossover trial reported on daily ratings of leg sensation, restlessness, and daytime alertness. A statistically significant improvement was shown in all parameters for oxycodone (mean dose of 15.9 mg/day), including the findings of reduced periodic leg movements in sleep, arousals, and a better sleep efficiency on two nights of polysomnography.7

In 1993, Kaplan, Allen, Buchholz, and Walters4 reported the changes in periodic leg movements in sleep (PLMS) in six patients who had been previously identified with PLMS and were treated in a double-blind, crossover trial with placebo, propoxyphene, and levodopa. The low potency, mu receptor agonist propoxyphene at 100 and 200 mg showed a small reduction of the leg movements on home actigraphy and improvement in arousal. But the patients did not show a statistically significant reduction of periodic leg movements of sleep on laboratory polysomnography. Compared with propoxyphene, levodopa demonstrated superior improvement in home actigraphy, sleep laboratory, and alertness measures.4

There are no published reports on the comparative efficacy of different opioids.

Management Strategies for Restless Legs Syndrome Symptoms With Opioids

When selecting a therapy for RLS, the most effective agents with the least amount of side effects would prove ideal. The bulk of evidence to date supports dopamine agonists as the most efficacious and least problematic therapy for the largest number of patients. It is estimated that 60% to 80% of RLS patients initially respond to levodopa, ropinirole, pramipexole, and others. The long-term therapy with dopaminergic agents is often limited by side effects, particularly augmentation. As described in Chapter 31 on dopaminergic treatment, augmentation to dopaminergic agents varies from 9% up to 80% depending on medication, symptom severity, length of treatment with selected dopaminergic medications. Opioid medications in general have not been found to produce augmentation with the singular exception of the mixed opioid medication tamadol.23

Clinicians must first recognize that opioids are efficacious and can generally be used with limited complications.24 Treatment algorithms recognize that opioids can be considered as first-line therapy under special circumstances, but opioids are more commonly considered appropriate for patients who have developed side effects on other therapy or have very severe RLS. The patient with severe RLS is believed to have a higher likelihood of earlier presentation of augmentation. Opioids may also have a role in combination therapy, reducing side effects when high dosage of any medication is needed to alleviate symptoms.

Various strategies with opioid therapy are available when adverse effects to dopamine agonists present. Infrequently, moderate or severe RLS patients are unable to tolerate even a low dosage of ropinirole, pramipexole, or levodopa. Although low-potency opioid agents might be considered, it is more likely that patients will respond to moderate-potency agents such as hydrocodone or oxycodone. Hydrocodone or oxycodone at 5 mg, 7.5 mg, or 10 mg PO at bedtime is usually well tolerated and offers benefit for the urge to move, motor restlessness and sleep. The primary disadvantage of hydrocodone or oxycodone is a half-life of 3 to 4 hours that may be insufficient to sustain benefit in patients with symptoms that develop in the evening or later in the night. Two or more doses of hydrocodone or oxycodone may be required to cover evening and nighttime symptoms.

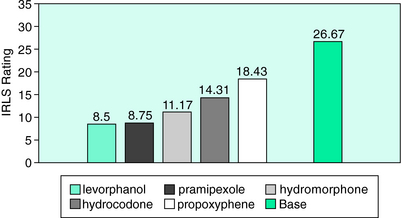

In a study of comparative efficacy of different medications,24 Becker examined the response of different opioids in a subset of 18 severe RLS patients using the earliest version of the RLS Rating Scale. These patients had been treated with levorphanol tartrate, a high-potency and long-acting synthetic opioid, at an average dosage of 3.2 mg/day for a mean of 5.1 years. Due to a change in DEA manufacturing license, levorphanol was abruptly unavailable, leading to a naturalistic study of the therapeutic efficacy of propoxyphene, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone in these severe RLS patients who had responded well to levorphanol. Propoxyphene up to 185.3 mg/day offered only mild benefit to these severe patients. When hydrocodone at a mean dosage of 18.2 mg/day was offered, the patients experienced a moderate degree of improvement. On initiation of hydromorphone at a mean dosage of 7.06 mg/day, the patients rated themselves to be moderately or more improved. As 4 of the 18 patients had not previously received a dopamine agonist, they received pramipexole and reported excellent benefit. Figure 32-1 shows the changes in rating on the RLS scale at baseline and with the various opioid agents.

Fear of Addiction and Adverse Events When Using Opioids in Restless Legs Syndrome

When considering the question of psychological dependence, the physician must be aware of the potential for insufficient dosing by patient and physician. The issue of dosage escalation in psychological dependence presumes that an expected therapeutic dosage was obtained. It is the natural tendency of the patient and physician to use the lowest potential dosage at the lowest frequency when initiating therapy. In such circumstances, inadequate dosing of effective therapy for RLS can occur. When a low dosage of the opioid agent (or a lower-potency opioid agent) has offered temporary benefit for 1 to 8 weeks, the physician should recognize that the therapeutic level to treat RLS has not been attained. Dosage increase would then be appropriate. In general, the patients without addiction potential eventually reach a dosage that results in sustained relief of RLS symptoms and the same therapeutic dosage of opioid will be maintained over time.

Walters and colleagues22 offer support and guidance about the long-term uses of opioids for RLS. They reported on 113 RLS patients from three centers who had received opioid therapy either alone or in combination with other treatments. Of the 36 patients who received opioids as their sole therapy, 20 continued on stable doses of opioid medication for a mean of 5.9 years. Only one of the 36 patients was discontinued from therapy because of concerns regarding addiction. Seven patients who had been treated for 1 to 15 years underwent polysomnography. Three of the seven patients either developed or showed an exacerbation of sleep apnea. The authors recommended that patients taking chronic opioid therapy should be closely monitored for sleep disordered breathing.

Conclusion

Opioid agents can be very effective in managing the symptoms of RLS. Opioid agents prove particularly beneficial for patients who have developed augmentation on dopamine agonists or have experienced problematic side effects from any other therapy. The most severe patients with RLS are appropriate candidates for opioid agents as first-line therapy. Although patients can benefit from moderate potency agents such as hydrocodone and oxycodone, high-potency levorphanol or methadone offer a longer therapeutic benefit with manageable side effects. If a patient has misused other psychoactive agents, addiction, physical dependence, and psychological dependence are risks and opioid therapy should be avoided. For any patient who has used opioids for months or years, a taper of medication must occur to avoid withdrawal. Long-term use also requires monitoring for adverse events, particularly daytime sleepiness or exacerbation of respiratory disturbance, including upper airway resistance syndrome or obstructive sleep apnea. Although the prescription of opioids requires respect for their risks and the acceptance of regulatory monitoring, physicians should recognize that up to 20% of their patients with RLS will significantly benefit from either monotherapy or combination therapy with opioids.

1. Willis T. The London Practice of Physick. London, Bassett, Dring, Harper, and Crook, 1692.

2. Ekbom K. Restless legs: A clinical study. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1945;158:1-123.

3. Ekbom KA. Restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1960;10:868-873.

4. Kaplan PW, Allen RP, Buchholz DW, Walters JK. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the treatment of periodic limb movements in sleep using carbidopa/levodopa and propoxyphene. Sleep. 1993;16:717-723.

5. Lauerma H, Markkula J. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with tramadol: An open study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:241-244.

6. Kavey N, Walters AS, Hening W, et al. Opioid treatment of periodic movements in sleep in patients without restless legs. Neuropeptides. 1988;11:181-184.

7. Walters AS, Wagner ML, Hening WA, et al. Successful treatment of the idiopathic restless legs syndrome in a randomized double-blind trial of oxycodone versus placebo. Sleep. 1993;16:327-332.

8. Trzepacz PT, Violette EJ, Sateia MJ. Response to opioids in three patients with restless legs syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:993-995.

9. Ondo WG. Methadone for refractory restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2005;20:345-348.

10. Walters AS. Review of receptor agonist and antagonist studies relevant to the opiate system in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2002;3:301-304.

11. Hening WA, Walters A, Kavey N, et al. Dyskinesias while awake and periodic movements in sleep in restless legs syndrome: Treatment with opioids. Neurology. 1986;36:1363-1366.

12. Winkelmann J, Schadrack J, Wetter TC, et al. Opioid and dopamine antagonist drug challenges in untreated restless legs syndrome patients. Sleep Med. 2001;2:57-61.

13. Montplaisir J, Lorrain D, Godbout R. Restless legs syndrome and periodic leg movements in sleep: The primary role of dopaminergic mechanism. Eur Neurol. 1991;31:41-43.

14. Scherbaum N, Stuper B, Bonnet U, Gastpar M. Transient restless legs-like syndrome as a complication of opiate withdrawal. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36:70-72.

15. Freye E, Levy J. Acute abstinence syndrome following abrupt cessation of long-term use of tramadol (Ultram): A case study. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:307-311.

16. Chesson AL, Wise M, Davila D, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Report. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 1999;22:961-968.

17. Silber MH, Ehrenberg BL, Allen RP, et al. An algorithm for the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:916-922.

18. Telstad W, Sorensen O, Larsen S, et al. Treatment of the restless legs syndrome with carbamazepine: A double blind study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:444-446.

19. Allen R, Becker PM, Bogan R, et al. Ropinirole decreases periodic leg movements and improves sleep parameters in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:907-914.

20. Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et al. Therapy with Ropinirole; Efficacy and Tolerability in RLS 1 Study Group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92-97.

21. Winkelman JW, Sethi KD, Kushida CA, et al. Efficacy and safety of pramipexole in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2006;67:1034-1039.

22. Walters AS, Winkelmann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Long-term follow-up on restless legs syndrome patients treated with opioids. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1105-1109.

23. Earley CJ, Allen RP. Restless legs syndrome augmentation associated with tramadol. Sleep Med. 2006;7:592-593.

24. Becker PM. Case management of 64 patients with moderate to severe restless legs syndrome [abstract]. Sleep. 2004;27(suppl):296.