47

Operative delivery

Introduction

The phrase ‘operative delivery’ is used to describe both instrumental vaginal delivery and caesarean section. It may be indicated to expedite delivery in the presence of fetal distress, or for ‘delay’ or failed progress, despite good contractions and maternal effort. The choice between instrumental delivery and caesarean depends partly on the stage of labour, with instrumental delivery possible only in the second stage; even then, specific criteria must be met. Caesarean section can be used in both the first and second stages of labour and after a failed or abandoned attempt at instrumental delivery.

Instrumental vaginal delivery

The most common indications for instrumental delivery are presumed fetal distress (e.g. heart rate abnormalities, meconium, low pH on fetal blood sampling) and second-stage delay. The criteria in Box 47.1 must be fulfilled before the procedure can be carried out.

A careful assessment is required prior to instrumental delivery, beginning with abdominal palpation. There should be no head palpable above the symphysis pubis although occasionally one-fifth is palpable in occipitoposterior positions. One of the most difficult parts of an instrumental delivery is being completely certain of the fetal head position prior to applying the forceps or ventouse (also known as vacuum-device). A systematic examination should determine the orientation of both the anterior and posterior fontanelles as the most common mistake is diagnosing an occipitoanterior position when in fact it is occipitoposterior. If there is a suspicion from palpation of the sutures that the fetal head is occipitotransverse, it is often helpful to try to feel for an ear anteriorly under the symphysis pubis. Some obstetricians use transabdominal ultrasound to confirm the position of the fetal head, others will seek a second opinion, or re-examine the patient in an operating theatre with good anaesthesia, where early recourse to caesarean section is possible. Incorrect assessment of the fetal head position or station results in a higher rate of failed instrumental delivery and morbidity for the mother and baby.

Operative vaginal delivery requires a multidisciplinary approach to maximize the likelihood of success and minimize maternal and fetal trauma. In addition to the attending midwife, a practitioner experienced in neonatal resuscitation should be present and the anaesthetist is frequently involved in the provision of adequate analgesia. Umbilical artery and vein acid–base status should be routinely recorded immediately after delivery.

The choice is between forceps and the ventouse.

Forceps delivery

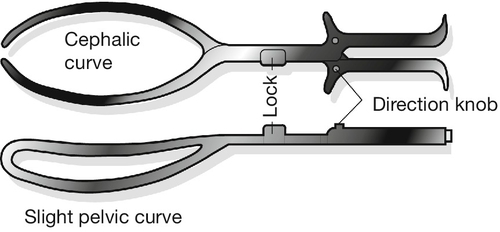

There are three main types of obstetric forceps (Fig. 47.1):

Fig. 47.1Selected types of forceps and ventouse cups.

The forceps, from left to right, are Kielland’s, Haig Ferguson’s and Wrigley’s. The orange tubing is attached to an O’Neill occipitoanterior metal cup, and the blue ventouse is a silastic cup.

1. Low-cavity outlet forceps (e.g. Wrigley’s, see History box), which are short and light and are used when the head is on the perineum

2. Mid-cavity forceps (e.g. Haig Ferguson’s, Neville-Barnes’, Simpson’s, see History boxes), for use when the sagittal suture is in the anteroposterior plane (usually occipitoanterior)

3. Kielland’s forceps (see History box) for rotational delivery to an occipitoanterior position. The reduced pelvic curve allows rotation about the axis of the handle.

Low- or mid-cavity non-rotational forceps

The mother should be placed in the lithotomy position with her bottom just over the edge of the bed (the bottom half of the bed often lifts away). Using an aseptic technique, the perineum is cleaned and draped, the bladder emptied, and the vaginal examination findings rechecked. A pudendal block and perineal infiltration (local anaesthesia) are inserted if required, and the forceps assembled discreetly in front of the perineum before application, care being taken to ensure that the pelvic curve of each blade will be sitting over the malar aspect of the baby’s head, convex towards the baby’s cheeks. Traction is applied in conjunction with the uterine contractions and maternal effort, encouraged by the attending midwife. The rest of the technique is shown in Figure 47.2.

Fig. 47.2Outlet forceps delivery with Wrigley’s forceps.

The handle in the operator’s left hand is inserted to the mother’s left side by placing the right hand into the vagina to prevent injury and slipping the blade between the hand and baby’s head between contractions (A). Opposite hands are used to insert the right blade, and the blades are locked into position by lowering the handles and allowing articulation to occur gently. Traction is applied by pulling initially downwards at an angle of ~ 60°; maternal pelvis to obstetrician’s pelvis if the obstetrician is sitting (B); with the direction of traction becoming horizontal and then upwards as the baby’s head advances over the perineum (C). It is usual to perform an episiotomy as the vulva stretches, but occasionally, as here, this may not be necessary, especially in a parous woman. The forceps are removed after delivery of the baby’s head and the remainder of the baby delivered as normal (D).

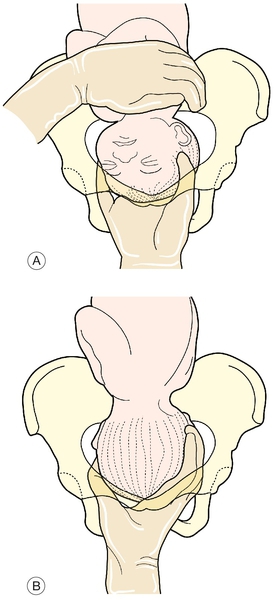

Rotational forceps

These forceps, known as Kielland’s forceps (Fig. 47.3), lack the pelvic curve of non-rotational forceps and can be applied directly to the baby’s head, if occipitoposterior, to allow gentle rotation to occipitoanterior. After rotation, delivery is as for the mid-cavity forceps. If the baby’s head is occipitotransverse, the blades may be applied directly or the anterior blade applied posteriorly before being ‘wandered’ past the baby’s face to the anterior position (Fig. 47.4). These forceps require considerable skill and may be associated with greater maternal injury than rotational ventouse. They should only be used by experienced obstetricians.

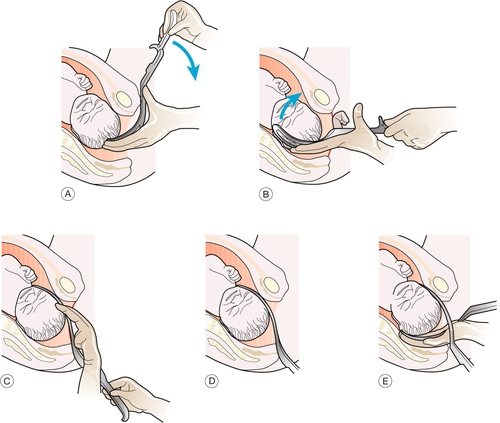

Fig. 47.4Delivery with Kielland’s rotational forceps.

(A) The anterior blade is initially applied posteriorly. (B,C,D) It is then ‘wandered’ to the anterior position across the baby’s face. (E) The posterior blade can then be applied and the baby’s head rotated to the occipitoanterior position.

‘Manual rotation’ of the head is sometimes possible, and it is usual to use the right hand for left occipitotransverse or left occipitoposterior (LOT/LOP) positions (Fig. 47.5) and the left hand for right occipitotransverse or right occipitoposterior (ROT/ROP) positions. The head is grasped transversely and rotated with a pronation movement. Alternatively, it may be possible to achieve purchase on the head using the fingertips in the lambdoid sutures. Some operators prefer to rotate during a contraction to minimize the risk of disengaging the head up out of the pelvis. If rotation is successful, it is almost always necessary to hold the new position with one hand while applying non-rotational forceps with the other to prevent the head rotating back again. Delivery with forceps is then completed in the usual way.

Ventouse

Whether to use ventouse or forceps remains an area for debate, but depends to a significant degree on operator experience and preference. Ventouse has the theoretical advantage that less pelvic space is required – with forceps the diameter of the presenting part includes both the fetal head and the width of the forceps, whereas with the ventouse it is only the diameter of the head which needs to be delivered.

The use of ventouse compared to forceps is associated with an increased risk of failure, more neonatal cephalhaematomas and retinal haemorrhages, and more low Apgar scores at 5 min but less anaesthesia requirements and less maternal perineal or vaginal trauma. No differences in morbidity between ventouse and forceps deliveries were found in the one study that followed-up mothers and children for 5 years. The use of a soft silastic cup rather than a metal vacuum extractor cup is associated with more failures but fewer neonatal scalp injuries. Silastic cups are therefore often used for occipitoanterior deliveries and a metal occipitoposterior cup for transverse and posterior malpositions. Disposable cups (rotational and non-rotational) are available; these produce a vacuum using a hand-powered pump and are suitable for single use. The same criteria for use apply to ventouse delivery as to forceps (Box 47.1).

The cup should be placed in the midline overlying, or just anterior to, the posterior fontanelle in order to encourage flexion of the head. Failure to correctly position the cup is the commonest reason for ventouse failure. Suction is applied, care being taken to ensure that the vaginal skin is not included under the cup. Traction is also applied downwards as for forceps, but delivery is much more likely to be successful if traction is timed with contractions and maternal effort (Fig. 47.6). The risk of significant fetal injury is increased with the duration of application (p. 407).

The ventouse cup is applied in the midline overlying, or just anterior to, the posterior fontanelle, care being taken to ensure that the vaginal skin is not included under the cup. Traction is then applied to coincide with maternal effort.

Although it has been suggested that ventouse should not be used at gestations of less than 36 weeks because of the risk of cephalhaematoma and intracranial haemorrhage, a case–control study suggests that this restriction may be unnecessary. Nonetheless, caution is still required. There is minimal risk of fetal haemorrhage if the extractor is applied after fetal blood sampling or application of a fetal scalp electrode. No significant scalp bleeding was reported in two randomized trials comparing forceps and ventouse. The ventouse is contraindicated with a face presentation or if there is a possibility of a fetal bleeding disorder.

Forceps delivery before full dilatation of the cervix is contraindicated and ventouse delivery before full dilatation should only be considered in special circumstances and with a very experienced operator.

Caesarean section

Caesarean section (see History box) may be:

![]() pre-labour – this can be elective or planned, for example with asymptomatic placenta praevia, severe fetal growth restriction, pre-eclampsia, breech presentation, unsuitability for vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC), maternal request or as an emergency, for example following an abruption

pre-labour – this can be elective or planned, for example with asymptomatic placenta praevia, severe fetal growth restriction, pre-eclampsia, breech presentation, unsuitability for vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC), maternal request or as an emergency, for example following an abruption

![]() in labour (i.e. emergency), usually for the reasons listed under ‘forceps’ but the cervix is not fully dilated or the mother is unsuitable for vaginal delivery.

in labour (i.e. emergency), usually for the reasons listed under ‘forceps’ but the cervix is not fully dilated or the mother is unsuitable for vaginal delivery.

Maternal mortality is higher for emergency caesarean section than for elective. Overall, there is also significant morbidity from haemorrhage, infection and thromboembolic disease. Deaths from thromboembolism have been dramatically reduced by the widespread use of appropriate thromboprophylaxis (low molecular weight heparin, early mobilization, hydration).

Lower uterine segment caesarean section is by far the most commonly used technique and has a lower rate of subsequent uterine rupture, together with better healing and fewer postoperative complications. A ‘classical’ caesarean section (vertical uterine incision involving the upper segment of the uterus) will provide better access for a transverse lie, with very vascular anterior placenta praevia, very pre-term fetuses (particularly after spontaneous rupture of the membranes), or large lower-segment fibroids. The risk of uterine scar rupture in subsequent pregnancies, following a vertical uterine incision is much greater than with the transverse incision and women are advised not to deliver vaginally following a classical caesarean section.

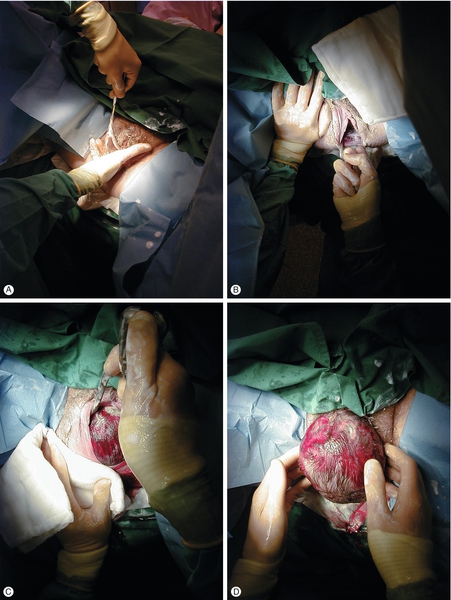

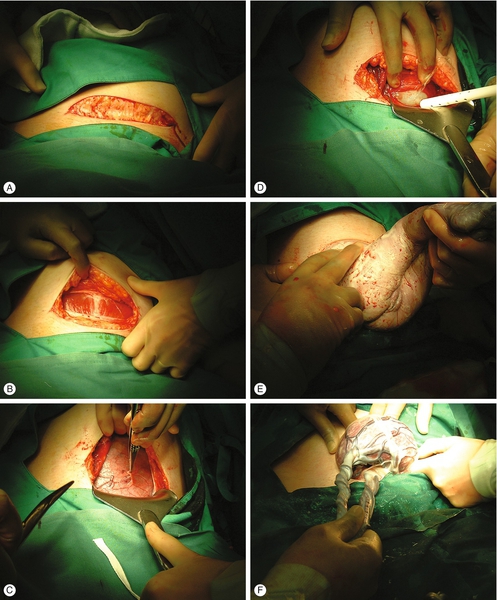

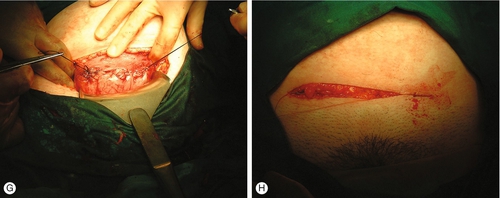

Preparation includes obtaining maternal consent, intravenous access, group and save (cross-match, where increased blood loss is anticipated), sodium citrate ± ranitidine (to reduce the incidence of aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs – Mendelson syndrome), appropriate thromboprophylaxis, antibiotic prophylaxis, anaesthesia (spinal, epidural or general) and bladder catheterization. The details of the operation are outlined in Figure 47.7.

Fig. 47.7Delivery by caesarean section.

The table should be tilted 15° to the left side (to reduce aortocaval compression and hypotension) and a lower abdominal transverse incision made, cutting through the fat (A) and the rectus sheath (B) to open the peritoneum. The bladder is freed (C) and pushed down, and a transverse lower segment incision is made in the uterus (D). If the presentation is cephalic, the head is then encouraged through the incision with firm fundal pressure from the assistant. Wrigley’s forceps are occasionally required. If the baby is presenting by the breech (as here), traction is applied to the baby’s pelvis by placing a finger behind each flexed hip to deliver the bottom first (E). If the lie is transverse, a leg should be identified and pulled through the uterine incision to help deliver the baby (i.e. internal podalic version). After delivery, syntocinon is given intravenously and after uterine contraction, the placenta is delivered (F). Haemostasis is obtained with clamps and a check is made to ensure that the uterus is empty and that there are no ovarian cystsThe incision is closed with two layers of dissolving suture to the uterus (G), one layer to the rectus sheath and one layer to the skin (H).

Caesarean section on maternal request

Women who have had a previous difficult delivery or adverse outcome may request an elective caesarean section for a subsequent birth. This may be influenced by both psychological and physical sequelae. Although in most cases a more straightforward delivery can reasonably be anticipated next time around, careful consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of an elective delivery is required.

In general, women with a previous caesarean section for a non-recurrent indication, e.g. breech, fetal distress or relative cephalopelvic disproportion secondary to fetal malposition (usually occipitoposterior position), should be offered a VBAC, but elective repeat caesarean section (ERCS) may also be considered. Women with a previous caesarean section are counselled by a senior obstetrician, ideally at the first antenatal visit and again at about 36 weeks’ gestation when a care plan can be finalized. Women who attempt VBAC have a vaginal delivery rate of approximately 60–70%. The risk of uterine rupture with attempted VBAC of spontaneous onset is approximately 1 in 200, being slightly higher if the labour is induced or contractions are stimulated with an oxytocin infusion.

Some women request an elective caesarean section for a first delivery, where there is no obstetric indication; the advantages and disadvantages need careful consideration before an informed decision is reached.