CHAPTER 46 Open Scapholunate Ligament Repair

Rationale

Dissociation between the carpal scaphoid and lunate is the most common pattern of wrist instability.1–3 Because scapholunate dissociation leads to progressive degenerative arthritis of the wrist,2,4,5 reduction and internal fixation is the preferred method of treatment, particularly in the acute setting.6–10 Owing to the small surface area and the high loads placed on the repaired ligament, a variety of capsular reconstructions (capsulodeses) have been described to augment scapholunate ligament repair. These procedures use the dorsal capsule or the dorsal radiocarpal and dorsal intercarpal ligaments, or both the capsule and ligaments, to help keep the scaphoid out of pathological flexion and the lunate out of excessive extension (Fig. 46-1).

Indications

Indications for direct ligament repair and capsulodesis include a documented dissociation with an adequate ligament still available for repair at the time of surgery, a reducible scapholunate relationship, and the absence of degenerative changes within the carpus. Although these procedures are best when performed early, some data suggest that the results do not depend on the interval between injury and surgical repair.11 Additional reconstructive options to treat scapholunate dissociation are discussed in subsequent chapters, including using the flexor carpi radialis tendon as a tenodesis and a screw, rather than smooth pins, to maintain the scaphoid and lunate relationship. Partial wrist fusions, such as between the scaphoid, trapezium, and trapezoid (scaphotrapeziotrapezoid fusion) or between the scaphoid and capitate (scaphocapitate fusion), which were previously popular are falling out of favor for scapholunate dissociation.

Contraindications

The main contraindication to direct ligament repair of a scapholunate dissociation is arthritic changes within the carpus. When the scaphoid and lunate become dissociated, a progressive pattern of wrist arthritis ensues. Wear begins at the radial styloid and progresses to involve the entire radioscaphoid articulation and then the midcarpal joint. The degree of arthrosis is not always apparent on plain radiographs of the wrist (Fig. 46-2). When degenerative changes are present, most notably in the scaphoid fossa of the radius, alternative salvage options are required, such as a proximal row carpectomy or a midcarpal (four-bone) fusion.

Surgical Technique

The procedure of direct scapholunate ligament repair with dorsal capsulodesis begins with a dorsal longitudinal incision centered over the scapholunate interval. The dorsal retinaculum is divided in line with the third compartment, and the extensor pollicis longus is retracted radially. The posterior interosseous nerve can be found on the radial floor of the fourth dorsal compartment. A neurectomy is performed because this nerve partly innervates the scapholunate ligament.12 The fourth dorsal compartment is subperiosteally reflected ulnarly to aid in the exposure, but its subsheath is not violated.

The wrist joint is exposed through a straight capsular incision. Care is taken not to elevate the radial capsular flap off of the radius. Alternatively, the radial flap can be elevated in a subperiosteal fashion, but this would need to be secured later to the dorsal aspect of the distal radius to complete the capsulodesis. The dorsal and membranous portions of the scapholunate interosseous ligament are evaluated. The ligament is typically torn off of the scaphoid remaining attached to the lunate. It can avulse off of the lunate, however, and remain attached to the scaphoid. Lastly, one occasionally observes central attenuation within the ligament proper. If there is little or no interosseous ligament remaining for repair, alternative surgical options can be considered.13–17

The dorsal aspect of the proximal pole of the scaphoid and corresponding scaphoid facet of the distal radius are inspected for degenerative changes. As noted previously, if significant degeneration exists, one needs to consider a salvage-type operation.5,18–20 Advanced radioscaphoid arthritis is a contraindication to direct ligament repair. If only slight pointing at the radial styloid exists, however, a limited styloidectomy can be done. Care is taken to protect the radial capsule during subperiosteal dissection for the styloidectomy.

Kirschner wires are inserted in a dorsopalmar direction into the scaphoid and lunate to be used as joysticks. Because significant force may be required to reduce the diastasis, 0.062-inch wires are typically used for this purpose. The scaphoid wire is placed in a slightly distal to proximal direction; the lunate pin is angled slightly from proximal to distal to facilitate subsequent rotation of the bones. A narrow trough is created next along the dorsal lunate or scaphoid with a bur or fine rongeur at the site of detachment. Although the repair was originally described using drill holes and Keith needles, newer miniature bone anchors can be used to aid in the repair. With the joint opened, the anchors can be placed (Fig. 46-3). It is sometimes easier to place the anchor sutures into the ligament in their anatomical position before the final fixation. This is especially true for the more proximal sutures, which may be difficult to work with when the bones are reduced, and this area rotates beneath the dorsal rim of the radius.

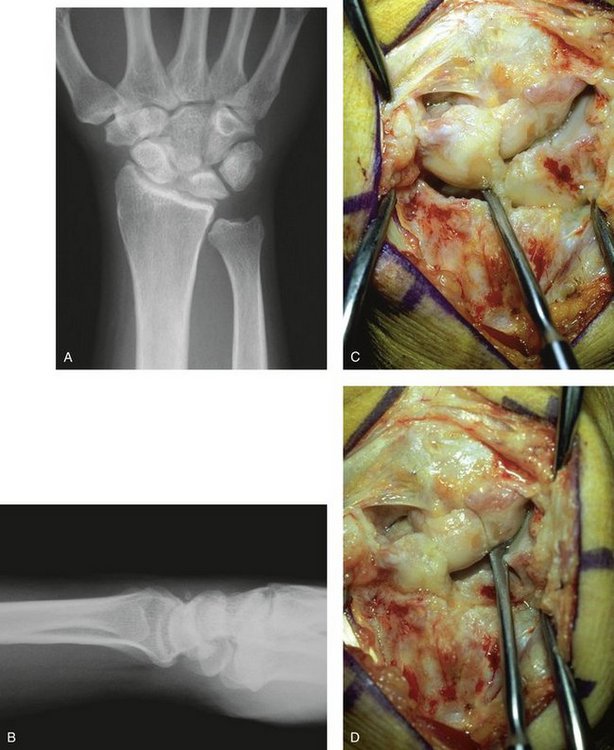

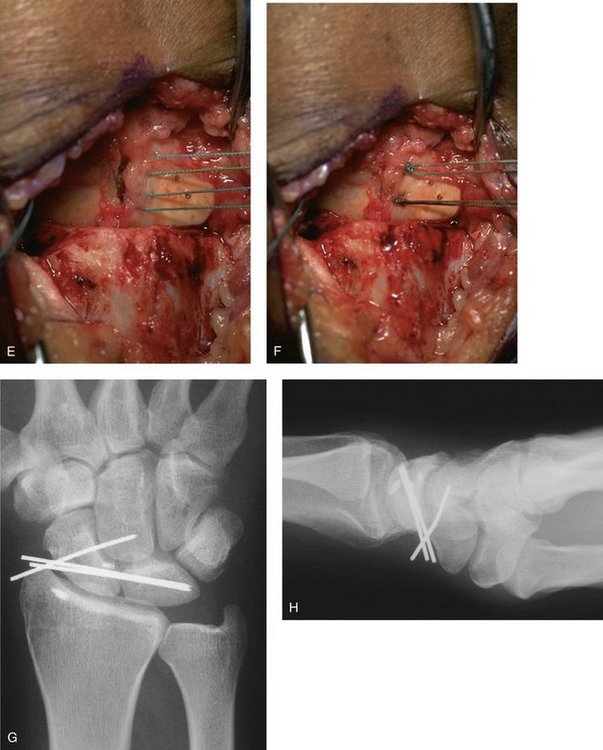

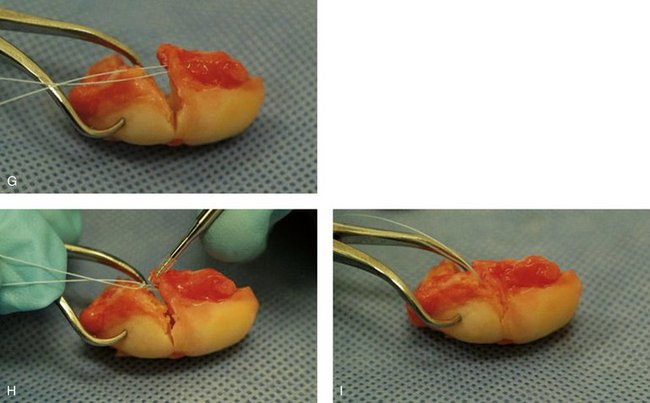

FIGURE 46-3 A and B, Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of a patient with a scapholunate dissociation. C, Intraoperative photograph depicting the bone anchors that have been placed into the scaphoid at the site of ligament avulsion. Note the Kirschner wires in the scaphoid and lunate being used as joysticks. D, The scapholunate dissociation has been reduced and secured with percutaneous Kirschner wires placed from the scaphoid into the lunate, and from the scaphoid into the capitate. The ligament is seen in the forceps. E and F, Sutures have been passed into the ligament (E) and tied completing the direct ligament repair (F). G and H, Postoperative posteroanterior (G) and lateral (H) radiographs. Note the reduction of the scapholunate relationship and the bone anchors in the scaphoid and distal radius for the dorsal capsulodesis performed in a “reverse” fashion in this case. I and J, Follow-up posteroanterior (I) and lateral (J) radiographs. K and L, Final wrist extension (K) and flexion (L) at follow-up. Note the loss of terminal wrist flexion, which is attributed to the capsulodesis.

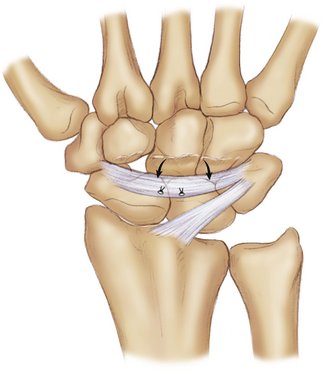

The joint is next reduced using the Kirschner wires by extending the scaphoid and flexing the lunate. Occasionally, the bones also have to be pulled together, supinating the scaphoid. In addition to flexion, the scaphoid pronates when it dissociates from the lunate.21,22 After reduction (slight over-reduction may be preferable), the bones are pinned with 0.045-inch Kirschner wires directed from the scaphoid into the lunate and from the scaphoid into the capitate. The reduction is checked and verified under fluoroscopy. With the scapholunate joint reduced, the ligament is repaired to the trough using the bone anchor sutures (see Fig. 46-3). If previously placed, these are tied under tension completing the repair. As described by Viegas and DaSilva,23 the proximal fibers of the dorsal intercarpal ligament can be incorporated into the repair. This intercarpal ligament passes transversely just distal to the scapholunate ligament and may normally reinforce this bony relationship (Fig. 46-4).

FIGURE 46-4 Diagram depicting the capsulodesis technique of Viegas and DaSilva23 in which the central aspect of the dorsal intercarpal ligament is pulled proximally and reattached to the scaphoid and lunate in an effort to reinforce the repair and restore anatomy.

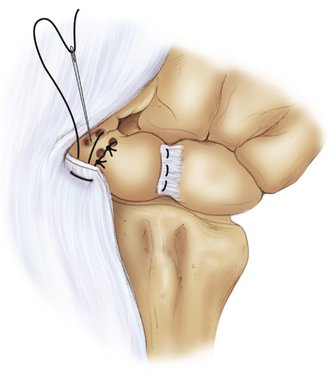

When the ligament is directly repaired, a secondary capsulodesis can be added. The original technique of dorsal capsulodesis was described by Blatt in 1987.7 He used a proximally based strip of the dorsal capsule off the radial aspect of the radius to tether and stabilize the distal scaphoid. Taleisnik modified Blatt’s technique to include a direct scapholunate ligament repair and an imbrication of the radial capsule to complete the capsulodesis (Fig. 46-5).11 Securing the radial capsule to the distal scaphoid provides a dorsal tether to resist subsequent scaphoid flexion.7 Although the capsulodesis was initially described using a palmar pullout suture, attachment of the radial capsule to the distal scaphoid also can be facilitated using a small bone anchor. Care must be taken to create a trough in the dorsal aspect of the scaphoid distal to the midwaist. This improves the mechanical advantage of the capsulodesis. With the radial capsule pulled distally under tension, the capsule is secured down to the scaphoid trough using the bone anchor sutures or with a pullout suture tied palmarly over a bolster. If a bone anchor is chosen, it is easiest to place it in the center of the trough before reduction and pinning of the scapholunate dissociation. The ulnar capsular flap is used to reinforce the repair by suturing it to the radial capsule. The extensor retinaculum is approximated leaving the extensor pollicis longus outside of the retinaculum, and the skin is repaired in the usual manner.

FIGURE 46-5 Schematic diagram of scapholunate ligament repair and capsulodesis as originally described by Taleisnik11 in which drill holes are placed through the scaphoid to facilitate repair. The newer miniature bone anchors are an alternative to this technique. The radial capsular flap, still attached to the distal radius, is advanced to the distal pole of the scaphoid to complete the capsulodesis. The ulnar capsule is imbricated over the top of this, completing the dorsal capsular reconstruction.

Alternative capsulodesis reconstructions have been described to augment the direct scapholunate ligament repair. Szabo and coworkers24,25 have modified the capsulodesis to incorporate the dorsal intercarpal ligament, as is discussed in a subsequent chapter. Kleinman26 has described using the dorsal intercarpal ligament as a capsulodesis by releasing it ulnarly and repairing it to the distal radius. Walsh and coworkers27 have described an alternative capsulodesis using the proximal half of the dorsal intercarpal ligament, which is sutured to the lunate. Because this capsulodesis does not cross the radiocarpal joint, it theoretically should not limit wrist flexion to the same degree.

Practical Tips

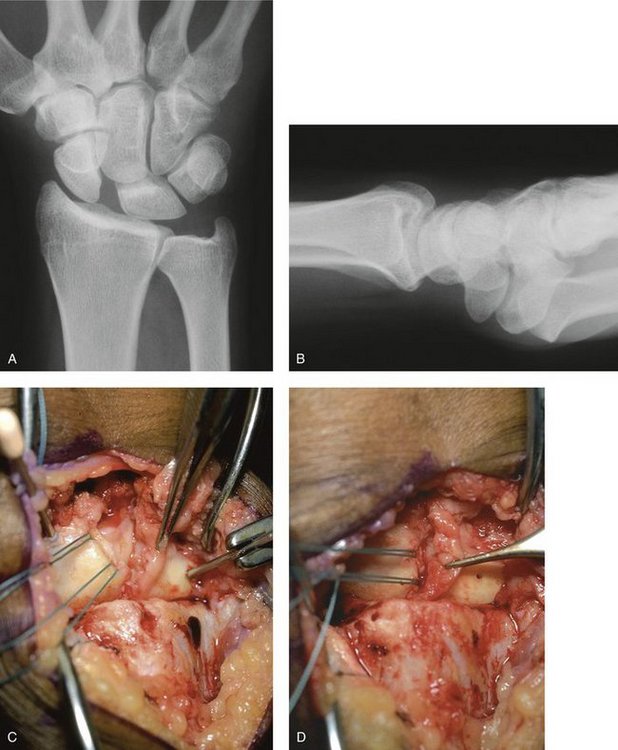

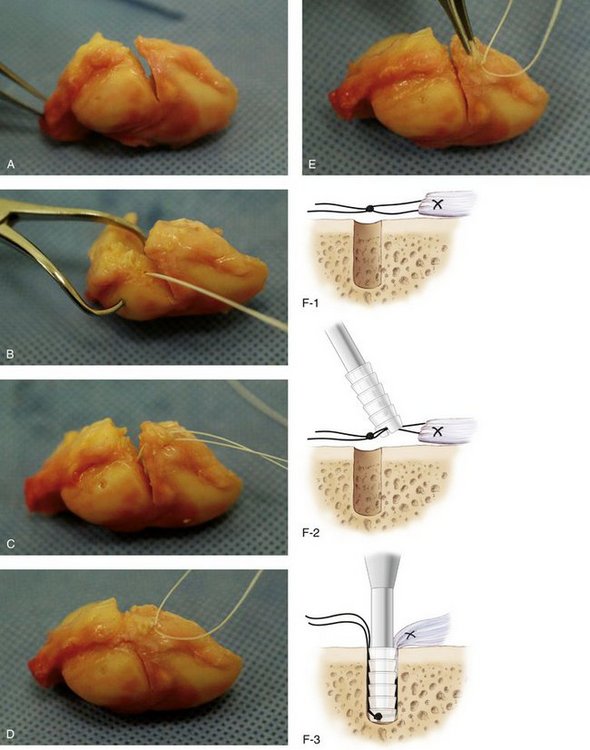

Using conventional bone anchors, it also is sometimes difficult to reattach the scapholunate ligament directly to the point of bony avulsion. Even if the knot is tightly tied, the ligament may not be completely approximated to the bony trough because it is difficult to “push” tissue down to the bony surface using this technique (Fig. 46-6). Newer anchors (originally designed for larger joints such as the shoulder) that are applied by first placing a locking stitch into the ligament edge and then driving this down into the bone may be more effective for scapholunate repair. We have been using these at our institution for several years and have found them to provide a more satisfying repair because they drag the ligament edge directly into the bony trough (see Fig. 46-6).

FIGURE 46-6 A, Cadaver specimen depicting the scaphoid, lunate, and interosseous ligament, which has been sectioned at its scaphoid attachment to simulate a ligament rupture. B, Conventional bone anchor placed into the insertion point. C and D, Sutures have been passed into the ligament (C) and tied to complete the simulated repair (D). E, Note how the edge of the ligament is not firmly attached to the bone edge. It can be difficult to “push” tissue to bone using conventional bone anchors for this repair. F, Diagram depicting newer V-Tak anchor (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) in which the sutures are first placed into the ligament with a locking stitch. The suture is tied, and the knot is driven into the bone using a fork on the anchor. This delivers the ligament edge to the bone better and completes the repair more securely. G, Suture placed in the ligament edge of a specimen with this technique. H, Note the bone anchor, which captures the knot and helps drive the ligament edge to the bone. I, Final repair using this technique. This latter technique has been shown experimentally to be superior with respect to pullout strength when used for the scapholunate ligament.

Finally, another technical difficulty involves proper tensioning of the radial capsule to complete the capsulodesis. Because it is occasionally difficult to push the thick dorsal capsular tissue down to the scaphoid trough under tension using a bone anchor (if sutured too tightly, it would not reach, and if too loose, it would not provide an adequate dorsal tether), one can alternatively fix the distal capsule to the scaphoid first. This “reverse capsulodesis” technique also is used if it was decided to perform a radial styloidectomy, or if the radial capsule was subperiosteally dissected off the radius during exposure. In this way, the capsule can be first secured distally under minimal tension. This ensures that the capsule is directly secured to the cancellous trough created in the scaphoid. The radial capsule can be pulled taut proximally and secured to the radius under tension using an additional bone anchor.

Results

In 1992, we published our results of direct scapholunate ligament repair using the original capsulodesis as described by Taleisnik.11 The average time from injury to surgical repair was 17 months. Wrist motion at an average follow-up of 33 months was equal to the unaffected wrist in all planes except flexion (P < .001). This limitation is most likely related to the dorsal capsulodesis, which provides a tether limiting terminal scaphoid flexion. Patients must be counseled on the expected loss of terminal wrist flexion even in successful cases. This is rarely a functional problem. Using visual analog scales,28 peak and general levels of pain were significantly improved at follow-up (P < .001). Radiographically, the scapholunate gap was reduced from a mean of 3.2 mm preoperatively to 1.9 mm at follow-up.

Conclusion

Scapholunate dissociation can be treated successfully by direct ligament repair and dorsal capsular augmentation. Requirements include an adequate interosseous ligament identified at surgery and absent degenerative changes at the radioscaphoid articulation. The rationale for soft tissue repair is based on the premise that restoration of the normal intracarpal relationships would halt degenerative changes, while maximizing wrist motion and function. The dorsal capsulodesis provides a checkrein to excessive palmar flexion of the scaphoid. Since its initial description, several variations have been described, all using the dorsal capsule and dorsal wrist ligaments. Although all capsulodesis reconstructions that cross the radiocarpal joint may limit palmar flexion of the wrist, this is not a clinical problem.

1 Jones WA. Beware of the sprained wrist: the incidence and diagnosis of scapholunate instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:293-297.

2 Linscheid RL, Dobyns JH, Beabout JW, et al. Traumatic instability of the wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:1612-1632.

3 Taleisnik J. Carpal instability: current concepts review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:1262-1267.

4 Sebald S, Dobyns JA, Linscheid RL. The natural history of collapse deformities of the wrist. Clin Orthop. 1974;104:104-108.

5 Watson HK, Ballet FL. The SLAC wrist: scapholunate advanced collapse pattern of degenerative arthritis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1984;9:358-365.

6 Beckenbaugh RD. Accurate evaluation and management of the painful wrist following injury: an approach to carpal instability. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;15:289-300.

7 Blatt G. Capsulodesis in reconstructive hand surgery: dorsal capsulodesis for the unstable scaphoid and volar capsulodesis following excision of the distal ulna. Hand Clin. 1987;3:81-102.

8 Goldner JL. Treatment of carpal instability without joint fusion: current assessment. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1982;7:325-326.

9 Kleinman WB. Management of chronic rotary subluxation of the scaphoid by scapho-trapezium-trapezoid arthrodesis. Hand Clin. 1987;3:113-133.

10 Nathan R, Lester B, Melone CP. The acutely injured wrist: an anatomic basis for operative treatment. Orthop Rev. 1987;6:80-95.

11 Lavernia CJ, Cohen MS, Taleisnik J. Treatment of scapholunate dissociation by ligamentous repair and capsulodesis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1992;17:354-359.

12 Berger RA, Blair WF, Crowninshield RD, et al. The scapholunate ligament. J Hand Surg. 1982;7:87-91.

13 Eckenrode JF, Louis DS, Greene TL. Scaphoid-trapezium-trapezoid fusion in the treatment of chronic scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1986;11:497-502.

14 Kleinman WB. Long-term study of chronic scapholunate instability treated by scapho-trapezium-trapezoid arthrodesis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1989;14:429-445.

15 Peterson HA, Lipscomb PR. Intercarpal arthrodesis. Arch Surg. 1967;95:127-134.

16 Watson HK, Black DM. Instabilities of the wrist. Hand Clin. 1987;3:103-111.

17 Watson HK, Hempton RF. Limited wrist arthrodesis, I: the triscaphoid joint. J Hand Surg. 1980;5:320-327.

18 Cohen MS, Kozin SH. Degenerative arthritis of the wrist: proximal row carpectomy versus scaphoid excision and four-corner fusion. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26:94-104.

19 Inglis AE, Jones EC. Proximal row carpectomy for diastasis of the proximal carpal row. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:460-463.

20 Neviaser RJ. On resection of the proximal carpal row. Clin Orthop. 1986;202:12-15.

21 Kauer JMG. The mechanism of the carpal joint. Clin Orthop. 1986;202:16-26.

22 Short WH, Werner FW, Fortino MD, et al. A dynamic biomechanical study of scapholunate ligament sectioning. J Hand Surg. 1995;20:986-999.

23 Viegas SF, DaSilva MF. Surgical repair for scapholunate dissociation. Tech Hand Upper Extrem Surg. 2000;4:148-153.

24 Slater RR, Szabo RM, Bay BK, et al. Dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for scapholunate dissociation: biomechanical analysis in a cadaver model. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999;24:232-239.

25 Szabo RM, Slater RR, Palumbo CF, et al. Dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for chronic, static scapholunate dissociation: clinical results. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2002;27:978-984.

26 Kleinman WB: Dorsal capsulodesis (ligamentodesis) of the wrist. Presented at Advanced Techniques or the Treatment of Carpal Instability, American Society for Surgery of the Hand Annual Meeting, Seattle, October 5, 2000.

27 Walsh JJ, Berger RA, Cooney WP. Current status of scapholunate interosseous ligament injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:32-42.

28 Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet. 1974;2:1127-1131.