CHAPTER 104 Open Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms and Postoperative Assessment

Open repair of an AAA involves attaching a tube or bifurcated graft within the aneurysm sac. Occasionally, however, the native AAA is excluded from the graft and remains intact posterior to the aortic graft. The transperitoneal or the retroperitoneal approach may be used. In one study, there was no significant difference in mortality rates between the two procedures, and although retroperitoneal repair was associated with less frequent respiratory failure, it was also associated with more frequent wound complications.1

There are no strict anatomic contraindications to open repair of an AAA. However, there are many anatomic variations that must be taken into account. Coexisting aneurysms of the common iliac artery, especially if larger than 3 cm, should undergo exclusion during AAA repair. Attention should also be given to possible aneurysms of the hypogastric and external iliac arteries. The common and external iliac arteries may be severely affected by atherosclerotic disease, and may require arterial bypass grafting.2 Many pararenal aortic aneurysms are now repaired via the open surgical technique because of the frequent lack of a proximal implantation site sufficient for endovascular repair. These aneurysms require greater exposure than infrarenal aneurysms, and are technically more demanding. Repair of juxtarenal, pararenal, or suprarenal aneurysms require suprarenal clamping, which are associated with increased risk for renal damage because of ischemia.

POSTOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

Early Postoperative Complications

On the first postoperative day after open repair of an AAA, hypotension and cardiac and respiratory dysfunction are the most likely complications to occur. Between days 1 and 3, the most common complications are congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and respiratory failure. Pneumonia occurs most commonly between 4 and 7 days following surgery. The incidence of renal failure peaks within the initial 3 days following surgery and between 1 and 4 weeks postoperatively.2 A midline transabdominal incision is associated with higher postoperative rates of pulmonary complications, persistent ileus, and incisional hernias.

Overall, perioperative complications occur in up to 30% of patients. The organs most commonly affected are the heart, lungs, and kidneys. Cardiac-related complications, including arrhythmia, infarction, and congestive heart failure, occur in about 10% to 15% of patients after elective aneurysm repair. Perioperative renal dysfunction predicts a poorer prognosis and correlates with poor preoperative renal function. Insufficient management of pulmonary disease is also associated with a poorer prognosis.2

Early postoperative complications also include groin infections (in 2% to 3%), thromboembolism to the kidneys and lower extremities, and hemorrhage. Peripheral ischemia develops in less than 1% of patients postoperatively, but may occur because of damage to diseased arteries during cross clamping, iliac dissection, or peripheral embolization from aortic plaque. Spinal cord ischemia, which may result in paralysis, can occur secondary to a variety of differing factors. The artery of Adamkiewicz may arise below L3 in a minority of patients and ligation of a lumbar artery in the aneurysm sac in such a patient may lead to spinal cord ischemia. An additional cause is suprarenal or supraceliac cross clamping that compromises the spinal cord circulation. Small bowel infarction and colonic ischemia occur in 0.15% and 1% of patients undergoing elective AAA repair, respectively. Colonic ischemia most commonly develops because of ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery.2

Because of the course of the ureter over the iliac vessels, the ureter may be injured during open repair of AAAs. The ureter may have a variant course in patients with renal anomalies such as horseshoe kidney, further raising the likelihood for its injury. Ureteral fistulas with resulting urinomas may occur. Options for repair of ureteral injury include placement of a stent and reimplantation of the injured ureter into the bladder.2

Late Postoperative Complications

A common late postoperative complication is sexual dysfunction, including impotence and retrograde ejaculation. Erectile dysfunction may occur because of poor flow through the internal pudendal artery as a result of narrowing or occlusion, ligation of the internal iliac artery, an embolus or emboli in the distal pudendal arteries, or injury to the sympathetic nerves in the fascia surrounding the aorta. Other late complications include pseudoaneurysm formation, graft thrombosis, infection, aortoenteric fistula, aneurysm rupture, colonic ischemia, and peripheral embolism. These complications may affect up to 10% of patients.2

Postoperative Mortality and Survival

The postoperative mortality rate for elective open repair is approximately 5%; it is lower in younger healthier patients and higher in older at-risk patients. Risk factors that increase a patient’s risk of mortality following open aneurysm repair include advanced age, female gender, and any associated comorbidities. Additional factors include the experience of the operating surgeon, need for urgent (rather than elective) repair, and hospital volume (hospitals with higher surgical volumes generally have a lower mortality rate than those with lower volumes).2

Five-year survival of patients after successful elective open AAA repair is 60% to 70% and the 10-year survival rate is approximately 40%. These survival rates are lower than those of matched patients without AAAs, and the increased mortality is mostly to the result of manifestations of atherosclerosis, especially coronary artery disease.3

The few published reports of pararenal aortic aneurysm repair describe mortality rates that vary from 0% to 15.4%. Renal morbidity rates are high in such patients.4 In one study, there was a higher risk of overall perioperative mortality for patients who underwent open repair of juxtarenal and pararenal aortic aneurysms compared with those who underwent open repair of infrarenal aortic aneurysms (12% and 3.5%, respectively; P < .02).5

The mortality for ruptured AAA ranges from 15% to 50%, often caused by hemorrhagic shock, acute renal failure, myocardial infarction, respiratory insufficiency, or multiorgan failure.6 Mortality following open repair of a ruptured AAA is 30% to 40%.

Surgical Conversion from Endovascular Repair

Conversion from endovascular to open repair may be required for a number of reasons (Table 104-1).7 Older age, presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), wider infrarenal necks, and larger aneurysms have been associated with a higher rate of conversion. In one study, the mortality rate of patients who underwent emergency conversion operations was 40%.8

TABLE 104-1 Reported Reasons for Conversion from Endoluminal Graft (ELG) to Open Repair

| Primary Conversion | Secondary Conversion |

|---|---|

| Inability to gain access | Persistent endoleak |

| Aortic rupture | Aortic rupture |

| Failed deployment | Sealed endoleak with continued AAA expansion |

| Irreversible twisting of a nonmodular ELG | Apparently successful repair with continued expansion |

| Migration of ELG causing obstructed flow | Infection in the ELG |

| Endograft thrombosis | Renal arteries covered by the endograft |

From Myers K, Devine T, Barras C, Self G. Endoluminal versus open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysms 2009. Available at: http://www.fac.org.ar/scvc/llave/interven/myers/myersi.htm. Accessed October 6, 2009.

Clinical Presentation

Aortic Graft Infection

In cases of aortic graft infection occurring within 4 months of surgery, the patient may present with fever and a high white blood cell (WBC) count. Associated septicemia, wound infection, and graft dysfunction from thrombosis or hemorrhage from the anastomotic site may occur. Infections that occur more than 4 months postoperatively may present with more subtle signs and symptoms, and a fever may be absent. Such patients have a higher likelihood of presenting with signs of complications from their aortic graft infection, such as pseudoaneurysm, aortoenteric fistula, hydronephrosis, or osteomyelitis.9

Anastomotic Pseudoaneurysms

An anastomotic pseudoaneurysm is a potential late complication after repair of an AAA. It does not contain all the layers normally present in an arterial wall and are at risk for rupture. Anastomotic pseudoaneurysms most commonly result from arterial degeneration or infection.10 They may be aortic, iliac, or femoral. Degenerative anastomotic pseudoaneurysms may present in 0.2% to 15% of patients after AAA repair.11–13 One study10 found the most common manifestations of such pseudoaneurysms to be bleeding caused by rupture (30%) and sequelae of chronic limb ischemia (25%). Pseudoaneurysms may also manifest with symptoms caused by compression of adjacent structures or acute limb ischemia, or as an asymptomatic pulsatile mass.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Abdominal Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound is often used for screening but also for preoperative and postoperative evaluation of AAAs. On ultrasound, the size of an AAA can be measured; this serves as a good method to follow patients with smaller AAAs that do not meet the size criteria for surgery. If performed by trained personnel, ultrasound has a high sensitivity (approaching 100%) and specificity (approximately 96%) for the detection of infrarenal AAAs.14

Conventional X-Ray Catheter Angiography

Select patients with AAAs, such as those with suspected mesenteric ischemia, peripheral vascular occlusive disease or peripheral vascular aneurysms, renovascular hypertension, renal anomalies such as horseshoe kidney, or thoracoabdominal aneurysms, should undergo conventional angiography. Angiography may also be performed prior to planned endovascular repair to evaluate tortuous proximal aneurysm necks and tortuous iliac arteries.15

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Abdominal Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound can detect an aneurysm and investigate its size and location. As noted, ultrasound is limited in its ability to demonstrate the relationship of the proximal AAA to the renal arteries, and it is also limited in its ability to demonstrate the presence or absence of associated internal iliac artery aneurysms.16

Ultrasonographic imaging of the abdominal aorta should include imaging in the transverse and longitudinal planes. The maximum diameter of the AAA, proximal and distal extent, length and diameter of the proximal neck, diameter of the common iliac arteries, and diameter of the hypogastric arteries can be determined. Often, a B-mode ultrasound study is sufficient. Occasionally, color and Duplex scanning are useful, such as in the identification of an aortocaval fistula.15

Computed Tomography and Computed Tomographic Angiography

CT, especially CTA, can detect extension of an aneurysm into the iliac vessels, delineate the relationship of an aneurysm to the renal vasculature, and demonstrate the presence of renal anomalies and intra-abdominal pathology, such as masses.15 CT is particularly well suited for imaging the postoperative aorta following aortic graft repair.

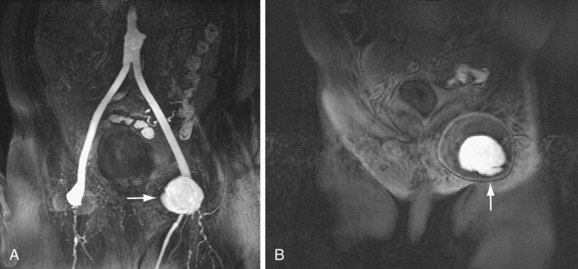

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Angiography

The protocol for postoperative assessment should include MRI (axial T1-weighted precontrast and postcontrast and T2-weighted [with fat suppression] sequences) and contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MRA. The ability of MRI and MRA to evaluate the proximal aspect of AAAs accurately, detect stenoses larger than 50% at the origin of the renal arteries, and assess patency of the superior mesenteric artery has been well established.16

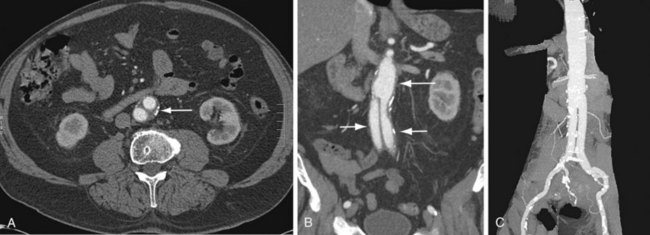

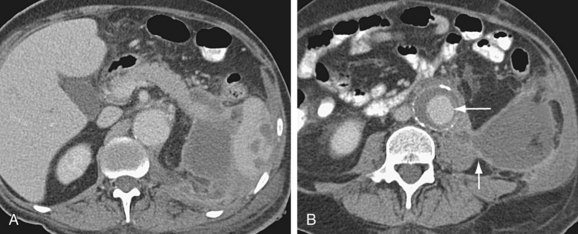

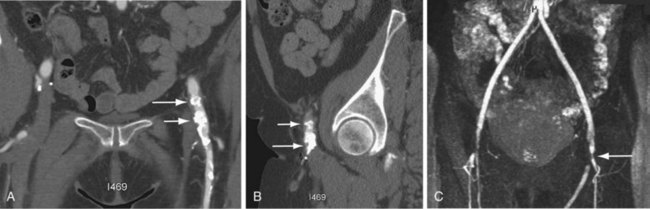

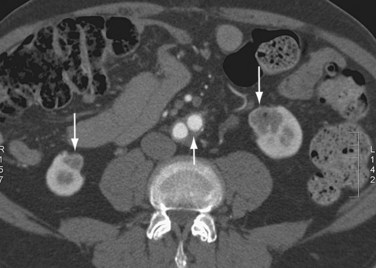

Normal Postoperative Appearance Following Open Surgical Repair

In a patient who has undergone an open surgical repair of an AAA, the graft may be seen as a round, well-demarcated structure within the aneurysmal sac. After intravenous contrast administration on CT, the graft is seen as an enhancing tubular structure surrounded by the native aorta in cases of proximal end-to-end anastomosis (Fig. 104-1). In cases of end-to-side proximal anastomosis, the enhancing graft may be seen running ventral and parallel to the nonenhancing diseased or aneurysmal aorta, which is now collapsed (Figs. 104-2 and 104-3). The graft bifurcation is at a higher level compared with the now occluded native bifurcation in cases of aortic-bi-iliac or aortobifemoral grafts. In cases of more complicated grafts such as combined unilateral aortoiliac with or without femoral to femoral bypass, knowledge of surgical history helps the interpreting physician to follow the graft as an enhancing tubular structure from the site of the proximal to distal anastomosis. MRA (Fig. 104-4) is also well suited for imaging the aortic and iliac graft components after surgery.

Aortic Graft Infection

Aortic graft infection occurs in 1% to 5% of reconstructions.17 This complication has mortality rates of 25% to 75%.18 Aortic graft infection may lead to graft occlusion and anastomotic hemorrhage, which may lead to aortoenteric fistula.

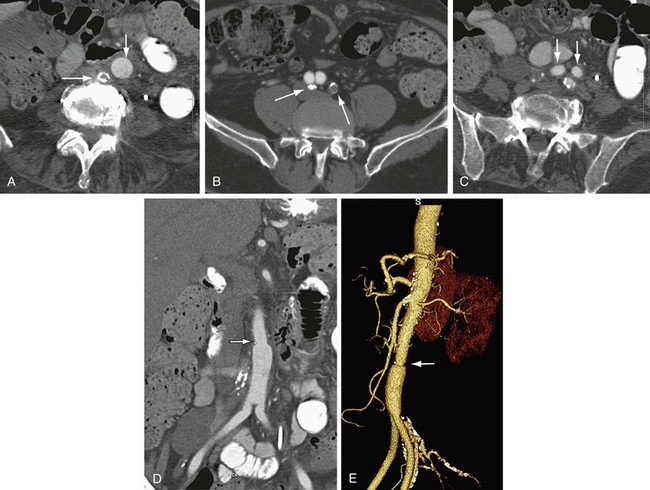

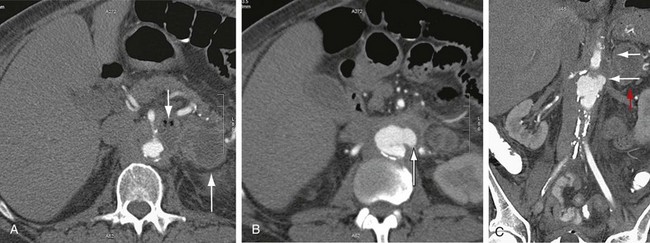

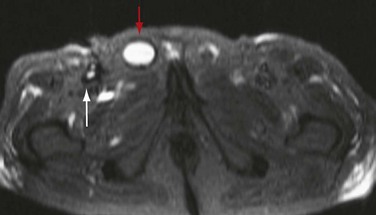

Graft infection may occur from a few days to many years after surgery. CT is considered the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of graft infection (Figs. 104-5 to 104-8). One study has shown that CT has a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 85% for the detection of perigraft infection, with or without associated aortoenteric fistula, when the criteria of perigraft fluid, perigraft soft tissue density, ectopic gas, pseudoaneurysm, or focal bowel wall thickening were used.19 CT-CTA can demonstrate persistent perigraft soft tissue density, fluid, and gas, characteristics associated with graft infection. However, abnormal perigraft soft tissue density may also represent hematoma, fibrosis, and/or postoperative changes. In this regard, MRI may be helpful because it has improved soft tissue contrast resolution and the improved ability to differentiate between subacute and chronic hematomas, thrombus, and fibrosis from perigraft fluid resulting from graft infection (Fig. 104-9).

Although the normal graft has surrounding fat attenuation in the early postoperative period, there should be less than 5 mm of soft tissue attenuation between the aneurysm wall and underlying graft. Persistent fluid or soft tissue attenuation around the graft may persist for up to 3 months after surgery. Similarly, pockets of gas around the graft may be present for up to 10 days after surgery, but persistence after about 4 weeks postsurgery suggests infection.20

A recent study has shown that positron emission tomography (PET)-CT has a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 91%, positive predictive value of 88% and negative predictive value of 96% for the diagnosis of vascular graft infection.21 PET alone, although highly sensitive, has low specificity and limited anatomic localization.

Aortoenteric Fistula

Secondary aortoenteric fistula is a rare but severe complication after abdominal aortic surgery, with mortality rates approaching 100%. This type of fistula accounts for most aortoenteric fistulas. They often result from infection near the proximal anastomosis between the aorta and prosthesis. It is estimated that 80% of secondary aortoenteric fistulas involve the duodenum; typically, its third and fourth parts are affected. These fistulae may occur at any time between 2 weeks and many years after surgery. The annual incidence ranges from 0.6% to 2%.18

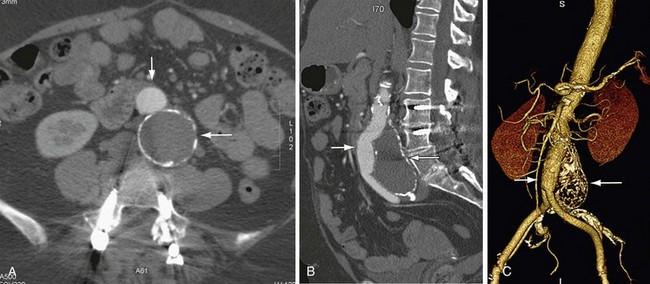

Although contrast-enhanced CT using a CTA protocol (Figs. 104-10 and 104-11) is the favored diagnostic modality,22 its sensitivity and specificity vary (from 40% to 90% and 33% to 100%, respectively). CT conducted with oral water-soluble contrast before and after contrast-enhanced CTA is preferred for patients who are not actively bleeding to delineate the fistula from the overlying duodenum (see Fig. 104-10). Prior to intervention, other modalities (e.g., endoscopy, radionuclide studies, angiography) may be needed to arrive at the diagnosis. Conventional x-ray catheter angiography may be combined with embolization and/or stent placement for therapy.

Many other entities, such as retroperitoneal fibrosis, infected aortic aneurysm, aortitis and, most commonly, perigraft infection, may mimic aortoenteric fistula. Features that suggest aortoenteric fistula include periaortic or intra-aortic gas, breach of the aortic wall, loss of fat planes, extravasation of aortic contrast agent into the bowel lumen or para-aortic space, retroperitoneal hematoma, and hematoma in the bowel wall or lumen. Perigraft air is more often seen in association with aortoenteric fistula than with aortic graft infection alone. The most specific feature of aortoenteric fistula is extravasation of intravenously administered contrast agent from the aorta into the bowel lumen.19 Similarly, extravasation of oral water-soluble contrast from the bowel into or around the aortic graft is a specific feature of aortoenteric fistula. Ectopic gas should not persist after 3 to 4 weeks postsurgery, which suggests infection and/or fistula formation to bowel.19

Aortoiliac Occlusive Disease

One study has investigated the sensitivity and specificity of color flow and Duplex ultrasound compared with digital subtraction angiography for determining the presence of stenosis at the distal anastomosis of aortoiliac and aortofemoral bypasses in long-term follow-up of 103 patients.23 Color flow imaging had a sensitivity of 89% in identifying the presence and location of distal anastomotic stenosis and a specificity of 95% of ruling out significant lesions. CTA and MRA (Fig. 104-12) can also be used for the investigation of graft thromboses and stenoses.

After aortoiliac surgery with Y grafts, dynamic CT has been shown to detect neointima formation, occlusion of the limbs of the bifurcation graft, and dilation and patency of the prosthesis, and correlates well with clinical findings in assessing for graft occlusion.24 MRA can be used as an alternative.

Renal Infarction

A remote renal infarct may appear as a focal area of decreased attenuation with cortical atrophy caused by scarring on CT (Fig. 104-13) or MRA (see Fig. 104-4) images.

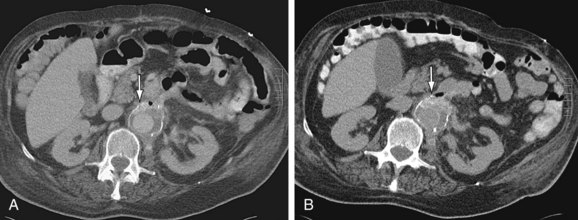

Anastomotic Pseudoaneurysms

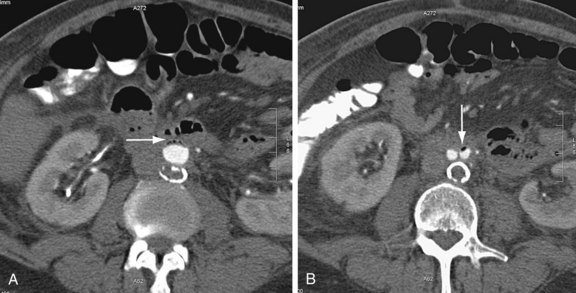

CT is the imaging modality of choice for the evaluation of anastomotic aortic pseudoaneurysms. A pseudoaneurysm appears as a collection of flowing blood in continuity with major arteries; it may also contain thrombus (Fig. 104-14). Hematomas or adjacent fluid collections may be apparent. Angiography may be used to evaluate the anatomy of a pseudoaneurysm further.

Ultrasound is often the first modality used to evaluate a pulsatile abdominal mass that may represent a pseudoaneurysm. On gray-scale sonography, pseudoaneurysms appear as anechoic structures associated with an artery. On pulsed Doppler, pseudoaneurysms often show turbulent flow in a “to-and-fro” pattern throughout the cardiac cycle, representing flow into the pseudoaneurysm during systole and flow out of the pseudoaneurysm during diastole.25

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most patients are followed postoperatively in the surgical intensive care unit. The patient’s hemodynamic profile is monitored continuously. Coagulation studies, complete blood count (CBC) and serum chemistries, and electrocardiograms are typically assessed. Patients with high or intermediate risk factors have troponin I levels drawn at 24 hours postprocedure and again at 96 hours postprocedure, or prior to discharge. Deep venous thrombosis and gastric ulcer prophylaxis are also typically initiated following surgical repair.2

Aortic Graft Infection

The most common organism responsible for aortic graft infection is Staphyloccus aureus; such infections often present in the early postoperative period. Most specimens that demonstrate white blood cells but are culture-negative contain Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antibiotic therapy is not usually curative. Previously, such infections were treated with excision of the graft with extra-anatomic reconstruction. However, aortic replacement with femoropopliteal veins has been proposed and has demonstrated reduced mortality and reinfection rates.26

Anastomotic Pseudoaneurysms

Surgical repair of anastomotic aortic pseudoaneurysms involves resection followed by placement of an interposition graft or vascular bypass. Endovascular repair is a good alternative,27 particularly for patients with multiple comorbidities. Some patients are not candidates for stent graft placement because of unusual anatomy or technical limitations of the stent graft.

KEY POINTS

Although perioperative mortality is higher in patients undergoing open repair of an AAA, reinterventions are more common in matched patients undergoing endovascular repair, and long-term mortality does not significantly differ between the groups.

Although perioperative mortality is higher in patients undergoing open repair of an AAA, reinterventions are more common in matched patients undergoing endovascular repair, and long-term mortality does not significantly differ between the groups. Anatomic considerations and comorbidities must be taken into account when deciding between endovascular and open repair for a patient with an AAA that meets the criteria for treatment.

Anatomic considerations and comorbidities must be taken into account when deciding between endovascular and open repair for a patient with an AAA that meets the criteria for treatment. Most AAAs are asymptomatic; when they rupture, a patient may present with acute abdominal, flank, or back pain.

Most AAAs are asymptomatic; when they rupture, a patient may present with acute abdominal, flank, or back pain. MRI/MRA and/or conventional x-ray catheter angiography may be helpful for preoperative imaging in select patients.

MRI/MRA and/or conventional x-ray catheter angiography may be helpful for preoperative imaging in select patients. Postoperative management of patients after open repair of an AAA includes careful monitoring of hemodynamic and respiratory status and electrolytes, and the implementation of preventive measures, such as prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis and gastric ulcer.

Postoperative management of patients after open repair of an AAA includes careful monitoring of hemodynamic and respiratory status and electrolytes, and the implementation of preventive measures, such as prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis and gastric ulcer. Various postoperative complications may occur after open repair, including but not limited to, the following: aortoenteric fistula, aortic graft infection, aortocaval fistula, aortoiliac occlusive disease, ischemic colitis, and renal infarction. CT-CTA is the postoperative imaging study of choice for imaging after open surgical repair of an AAA.

Various postoperative complications may occur after open repair, including but not limited to, the following: aortoenteric fistula, aortic graft infection, aortocaval fistula, aortoiliac occlusive disease, ischemic colitis, and renal infarction. CT-CTA is the postoperative imaging study of choice for imaging after open surgical repair of an AAA.Almahameed A, Latif AA, Graham LM. Managing abdominal aortic aneurysms: treat the aneurysm and the risk factors. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72:877-888.

Blankensteijn JD, de Jong SECA, Prinssen M, et al. Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2398-2405.

EVAR Trial Participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair and outcome in patients unfit for open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 2): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2187-2192.

EVAR Trial Participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2179-2186.

Hellmann DB, Grand DJ, Freischlag JA. Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm. JAMA. 2007;297:395-400.

Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:267-269.

Low RN, Wall SD, Jeffrey RB, et al. Aortoenteric fistula and perigraft infection: evaluation with CT. Radiology. 1990;175:157-162.

Orton DF, Leveen RF, Saigh JA, et al. Aortic prosthetic graft infections: radiologic manifestations and implications for management. Radiographics. 2000;20:977-993.

Upchurch GRJr, Schaub TA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:1198-1204.

1 Quinones-Baldrich WJ, Garner C, Caswell D, et al. Endovascular, transperitoneal, and retroperitoneal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: results and costs. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:59-67.

2 Zelenock GB, Huber TS, Messina LM, et al, editors. Mastery of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

3 Zarins CK, Gewertz BL. Atlas of Vascular Surgery, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

4 Jean-Claude JM, Reilly LM, Stoney RJ, et al. Pararenal aortic aneurysms: the future of open aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg.. 1999;29:902-912.

5 Faggioli G, Stella A, Freyrie A, et al. Early and long-term results in the surgical treatment of juxtarenal and pararenal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15:205-211.

6 Miani S, Giorgetti PL, Giordanengo F, Tealdi D. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: factors affecting the early postoperative outcome. Panminerva Med. 1998;40:309-313.

7 Cuypers PW, Laheij RJ, Buth J. Which factors increase the risk of conversion to open surgery following endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair? The EUROSTAR collaborators. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;20:183-189.

8 Böckler D, Probst T, Weber H, Raithel D. Surgical conversion after endovascular grafting for abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2002;9:111-118.

9 Valentine RJ. Diagnosis and management of aortic graft infection. Semin Vasc Surg. 2001;14:292-301.

10 Marković DM, Davidović LB, Kostić DM, et al. Anastomotic pseudoaneurysms. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2006;134:114-121.

11 Hallett JWJr, Marshall DM, Petterson TM, et al. Graft-related complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Reassurance from a 36-year population-based experience. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:277-284.

12 Edwards JM, Teefey SA, Zierler RE, Kohler TR. Intra-abdominal paraanastomotic aneurysms after aortic bypass grafting. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:344-353.

13 Nevelsteen A, Suy R. Anastomotic false aneurysms of the abdominal aorta and the iliac arteries. J Vasc Surg. 1989;10:595.

14 Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:267-269.

15 Mansour MA, Labropoulos N, editors. Vascular Diagnosis. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005.

16 Tennant WG, Hartnell GG, Baird RN, et al. Radiological investigation of abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: comparison of 3 modalities in staging and the detection of inflammatory change. J Vasc Surg. 1993;17:703-709.

17 Seeger JM. Management of patients with prosthetic vascular graft infection. Am Surg. 2000;66:166-167.

18 Reilly LM, Altman H, Lusby RJ, et al. Late results following surgical management of vascular graft infection. J Vasc Surg. 1984;1:36-44.

19 Low RN, Wall SD, Jeffrey RB, et al. Aortoenteric fistula and perigraft infection: evaluation with CT. Radiology. 1990;175:157-162.

20 Orton DF, Leveen RF, Saigh JA, et al. Aortic prosthetic graft infections: radiologic manifestations and implications for management. Radiographics. 2000;20:977-993.

21 Keidar Z, Engel A, Hoffman A, et al. Prosthetic vascular graft infection: the role of 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1230-1236.

22 Mark AS, Moss AA, McCarthy S, McCowin M. CT of aortoenteric fistulas. Invest Radiol. 1985;20:272-275.

23 de Gier P, Sommeling C, van Dulken E, et al. Stenosis development at the distal anastomosis of prosthetic bypasses for aortoiliac occlusive disease. Incidence and accuracy of colour flow duplex in the diagnosis. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1993;7:237-244.

24 Tuchmann A, Hruby W. CT in aortobifemoral Y grafts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1985;8:187-190.

25 Brown PM, Kim VB, Lalikos JF, et al. Autologous superficial femoral vein for aortic reconstruction in infected fields. Ann Vasc Surg. 1999;13:32-36.

26 Bhargava S. Textbook of Color Doppler Imaging. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers; 2004.

27 Laganà D, Carrafiello G, Mangini M, et al. Endovascular treatment of anastomotic pseudoaneurysms after aorto-iliac surgical reconstruction. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1185-1191.

FIGURE 104-1

FIGURE 104-1

FIGURE 104-2

FIGURE 104-2

FIGURE 104-3

FIGURE 104-3

FIGURE 104-4

FIGURE 104-4

FIGURE 104-5

FIGURE 104-5

FIGURE 104-6

FIGURE 104-6

FIGURE 104-7

FIGURE 104-7

FIGURE 104-8

FIGURE 104-8

FIGURE 104-9

FIGURE 104-9

FIGURE 104-10

FIGURE 104-10

FIGURE 104-11

FIGURE 104-11

FIGURE 104-12

FIGURE 104-12

FIGURE 104-13

FIGURE 104-13

FIGURE 104-14

FIGURE 104-14